Putin’s Russia: Testing the limits of state-directed mobilization

First published at Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung.

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, it boasted a highly globalized economy with its own fraction of the transnational capitalist class. As such, it was vulnerable to Western sanctions and economic decoupling with the West. In 2021, its ratio of imports to GDP was 20.6 percent — lower than India and South Africa, but higher than China or Brazil. Western countries wagered that economic sanctions would be a powerful weapon against Russia’s war machine, and indeed, early into the war Russia’s own Central Bank predicted a 10 percent drop in GDP in 2022.

Ultimately, however, these negative predictions never materialized. Russia’s GDP declined by only 1.4 percent in 2022, and grew by 4.1 percent in 2023 and 4.3 percent in 2024. What are the sources of Russia’s economic resilience? And do they form a sufficient foundation for long-term economic stability?

Decoupling from the West

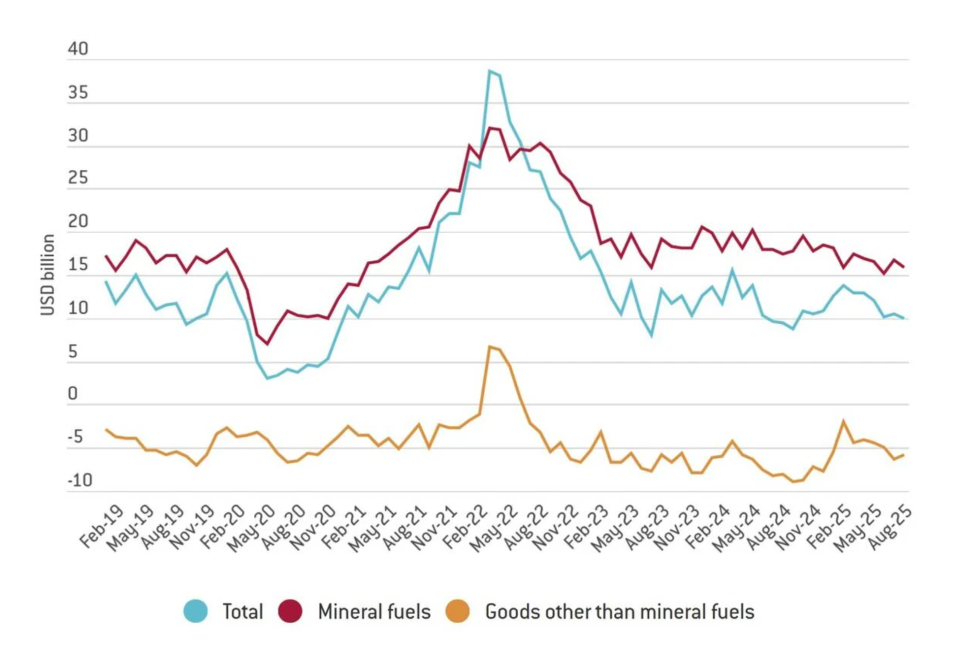

In 2021, Russia accounted for 13 percent of global oil exports. Replacing this amount of oil without causing a global market upheaval in the short term would have proven impossible. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the West ultimately introduced only mild sanctions on Russian oil, such as the 60-dollar price cap, clearly prioritizing stable supplies over geopolitical aims. Similarly, Russian grain and fertilizer exports were exempted from sanctions due to their crucial role in global food security. Consequently, overall Russian exports never collapsed as initially predicted, ensuring a steady supply of foreign currency to purchase imports and tax revenues to fund the war effort.

Some Russian exports did prove to be replaceable. Notably, Russian natural gas exports to the EU were largely replaced by US liquefied natural gas (LNG) and exports from other countries, which caused significant problems for Gazprom, the state-controlled energy corporation. Nevertheless, overall export revenues have remained at an acceptable level.

Russia also benefited immensely from the diversification of the global economy and rise of new, powerful trading partners in recent decades. In 2000, the G7 countries represented 65 percent of the global share of GDP, while BRICS countries collectively accounted for only 8 percent. By 2021, the G7’s share had declined to 45 percent, while the BRICS’s share had risen to 26 percent. Moreover, when measured in purchasing power parity terms, the BRICS’s share of global GDP (31.4 percent) was slightly higher than that of the G7 (30.8 percent).

The sheer scale of non-Western economies is not the only factor here — their complexity has increased as well. The Economic Complexity Index, which measures the sophistication of a country’s export basket, reveals that China climbed from forty-sixth place in the world in 2003 to nineteenth place in 2021. China is now an industrial powerhouse that not only offers some of the lowest prices on the world market, but can produce a wide variety of the most advanced goods and technology.

Had the invasion of Ukraine happened in 2000, Russia’s economy would have been hit much harder by Western sanctions. By the 2020s, however, non-Western countries could absorb most of Russia’s exports and provide most of the necessary imports. For various reasons including both geopolitical as well as purely commercial considerations, non-Western countries have proven reluctant to join Western sanctions against Russia. As a result, decoupling from the West proved feasible. It has proven particularly beneficial to the relationship between Russia and China, which has become an overwhelmingly important trading partner for the former over the last few years.

The role of the state

The Russian state has also occupied an increasingly important role in the Russian economy since the war began. Defence spending is expected to account for 7.5 percent of GDP in 2025. While not exactly a “war economy” comparable to World War I or II, where belligerents spent close to 50 percent of GDP on their respective militaries, Russia still represents one of the largest military economies in the world today in both absolute and relative terms.

State-directed military mobilization helped to bolster the economy’s resilience by absorbing unemployment and boosting domestic demand. Indeed, much of the GDP growth in 2023 and 2024 is attributable to military spending.

Since coming to power in 1999, Vladimir Putin has gradually built up state capacity in select government institutions, notably those responsible for economic management (the Central Bank, as well as the ministries of finance and economic development). Moreover, Russian business has developed flexible and resilient corporate structures. Skilful management in both public and private institutions contributed to the economy’s overall adjustment capacity.

Additionally, Russia already had experience in at least partial decoupling from the West and resultant economic crisis in 2014—2021. Adjustment mechanisms such as import substitution and new channels of state-business interaction developed during that period helped to adapt to the crushing sanctions of 2022 and beyond.

Winners and losers

Wartime economic changes produced new patterns of winners and losers — both in society at large and among the elite. These changes emerged as a result of several processes, including sanctions and the exodus of Western companies, the shifting geography of international trade, the expansion of the domestic military-industrial complex and reconstruction in occupied territories, as well as payouts to soldiers fighting in Ukraine.

These processes interact with each other in complex ways and often have indirect consequences. For example, waves of hiring in the military-industrial complex have put upward pressure on wages across the board. Wage growth in turn leads to inflation in the form of a wage-price spiral. The Central Bank targets inflation by raising the base rate. Along with tax increases, high interest rates reduce investment in civilian industries. While some economic sectors and segments of the population have benefitted significantly from these trends, others have proven far less fortunate.

Overall, Russia’s wartime economy is characterized by very low unemployment (2.2 percent in September 2025, compared to 4.3 percent in 2021) and strong growth in real wages (8.2 percent in 2023 and 9.1 percent in 2024, compared to 3.3 percent in 2021). That said, wage growth has proven highly uneven between regions and industries.

Among the “winners” in terms of rising bank deposits and incomes as well as poverty reduction are the regions with high army recruitment numbers, such as the republics of Tyva and Buryatia or the Altai Republic. Tyva, which by late 2023 counted the highest military losses in the country (140 soldiers killed in action per 100,000 people), also recorded the highest reduction in poverty in 2023 compared to 2021 (5 percentage points) and the strongest growth of local bank deposits (107.3 percent). Payouts to soldiers and their families in case of death have been so high that they are reflected in regional income and poverty statistics.

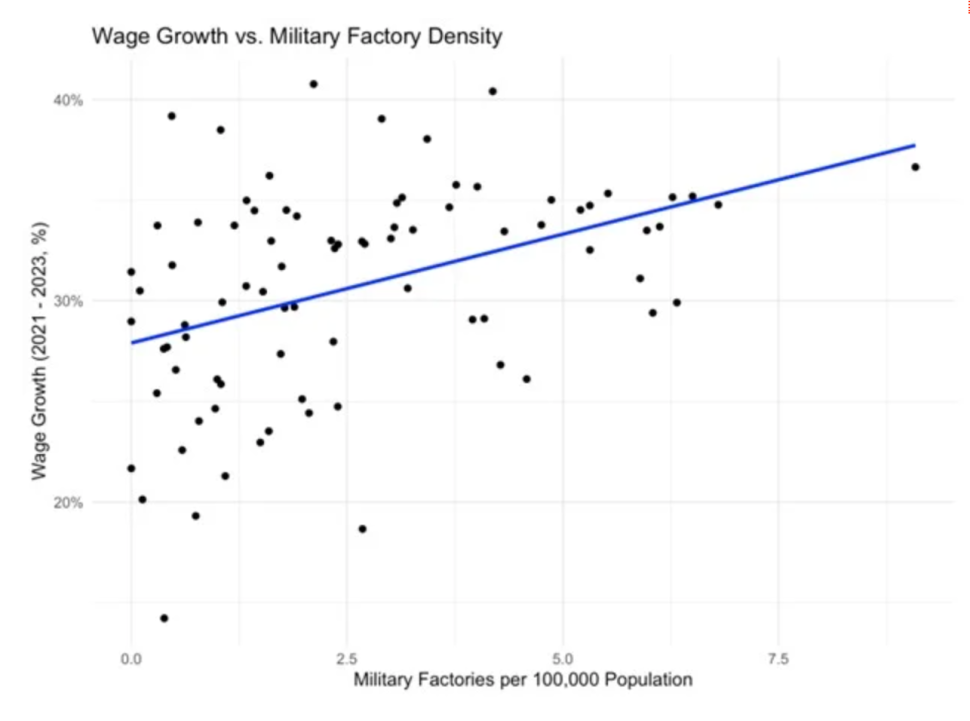

The expansion of the military-industrial complex has transformed Russia’s economic geography even further. In September 2024, authorities reported that 600,000 people had taken jobs in the military industry since February 2022. This growth has been concentrated in regions with existing military production facilities such as Nizhny Novgorod Oblast and Sverdlovsk Oblast. Consequently, these regions have experienced a faster rise in average wages than other regions. As can be seen in the table below, the number of military factories per 100,000 people in a region was associated with stronger wage growth in 2023 compared to 2021. A similar picture emerges from economic statistics, where military-related industries have seen the strongest growth in wages.

Large cities, particularly Moscow and Saint Petersburg, have been the losers in this situation. Their advanced post-industrial economies, although large and flexible, have suffered the most from deglobalization and the breakdown of international economic ties. In terms of wage growth, Moscow is in seventy-seventh place out of 85 regions (Russian statistics include occupied Crimea and Sevastopol), while Saint Petersburg is in sixty-sixth place. Both cities demonstrate similarly weak performance in terms of real income and bank deposit growth as well as poverty reduction compared to 2021.

The losers in terms of industries are oil and gas production, as well as public services such as education, healthcare, and social work. The oil and gas sector already boasted high salaries prior to the war and experienced significant turbulence and readjustment in the years since the invasion began. The weak wage growth in public services testifies to underinvestment, with the government prioritizing military spending over social expenditure.

Overall, the militarization of the Russian economy and forced import substitution acted as a corrective to post-Soviet economic tendencies. Since the early 1990s, Russia’s industrial working class and regions with a high concentration of Soviet-era industries (including the military-industrial complex) were among the losers of the economic transition, producing widespread misery and destitution. Since 2022, however, industrial workers and industrial regions have seen their fortunes improve somewhat.

Many Russians welcomed this development, viewing it as a remedy for one of their country’s most glaring economic and social imbalances. Nevertheless, the scale of this effect should not be overstated, and the weaknesses of the wartime economy remain significant.

Elite blowback

The war set in motion powerful processes, leading to a restructuring of the Russian business class as a whole. While a segment of the highly internationalized elite chose to cut ties with Russia, others doubled-down on their support for the current political order and have done their utmost to profit from the new situation since.

At least nine billionaires from the Russian Forbes list went as far as renouncing their Russian citizenship. Others completely divested from Russia and moved abroad while nominally remaining citizens. Other capitalists went all-in on Russia, rolling up the assets left by Western companies leaving the country. According to The Bell, the 2021 revenues of the companies that changed hands in this way amounted to roughly 3 trillion roubles, or 2.2 percent of Russian GDP. At the same time, the government launched an unprecedented wave of nationalizations. According to Novaya Gazeta, by March 2025 at least 2.56 trillion roubles’ (almost 2 percent of GDP) worth of assets had been nationalized.

Prior to the war, the Russian business community had access to a kind of “exit” option, as Russian corporations were simultaneously enmeshed in domestic state-capitalist networks as well as the global networks that constitute the transnational capitalist class. This arrangement allowed them to balance their domestic and foreign interests. The beginning of full-scale hostilities, however, forced Russian businessmen to make a choice: would they stay, or would they go? Most stayed in Russia, unwilling to let go of their primary revenue streams. This increased their dependence on the Kremlin, whose overwhelming influence over the Russian economy has only grown since 2022.

On the other hand, the lack of an “exit” option, coupled with the fear of losing wealth (e.g. due to nationalization), may eventually force the business class to develop strategies to leverage their political influence. Indeed, prior to the war, the political neutralization of the Russian business class had been so effective precisely because it maintained an exit option, able to choose partial or complete divestment over any attempts at political organization. Now that this route is closed off, Russia’s remaining billionaires may realize that they are stuck with Putin and that their wealth is under constant threat, necessitating new defensive strategies. Hence, it is becoming increasingly important for the Kremlin to manage the fears of the business class and maintain profit opportunities, lest dissatisfaction in the corporate sector grow.

Exhausting the wartime model

While the Russian economy has proven resilient in the face of powerful shocks, the limits of the wartime model are increasingly obvious. After two years of growth exceeding 4 percent, the Central Bank projects only 0.5–1 percent growth in 2025. Civilian industries are in sustained decline. High interest rates are a burden on the corporate sector, while investment — especially capital investment — is down.

The government has consistently raised taxes to finance its enormous military expenditures. For example, the corporate tax rate was raised from 20 to 25 percent, value added tax will increase from 20 to 22 percent in 2026, and personal income taxes are now collected on a progressive scale with a top rate of 22 percent (compared to 15 percent prior to the war).

Hundreds of thousands of skilled specialists have emigrated, and the gap in educational investment compared to top-performing economies, particularly China, has grown. Labour shortages are draining the civilian sector. Recent US sanctions against major Russian oil producers Rosneft and Lukoil left a sting, with Lukoil forced to sell off its assets in dozens of countries. Opportunities for technology transfer are now limited to non-Western countries, but China’s economically nationalist orientation makes it reluctant to share technologies with Russia (or anyone else, for that matter).

Moreover, the growth in real incomes for the lower classes is, to some extent, a statistical artefact. Prices are rising unevenly, with the cost of basic necessities like food, housing, and utilities rising faster than that of other goods and services. “Poor man’s inflation” is effectively higher than official inflation figures, largely negating income gains for the lowest-paid workers and pensioners.

In sum, despite initial signs of resilience and a surprising recovery, the Russian economy is now back on a trajectory of long-term stagnation — even if the nature of that stagnation differs from the pre-war period. Transnational ties are now largely limited to non-Western countries, and the war effort is draining resources from the civilian sector without producing any significant economic multiplier effect. Long-term prospects are further undermined by a decline in human capital and a lack of opportunities for technology transfer.

Thus, “Fortress Russia” is certainly resilient, but the development gap with the Global North and the most successful developing economies, particularly China, is widening. Under the current political and economic conditions, it seems highly unlikely that Russia will be able to catch up.

Ilya Matveev is a political scientist specializing in Russian and international political economy.