One year after 7 October, Gilbert Achcar discusses the future of Gaza, Lebanon and the regional conflict

First published at Ahram Online.

On 7 October this year, the Palestinians in Gaza marked one year of the devastating war that Israel inflicted on them hours after the Hamas Al-Aqsa Flood Operation struck the south of Israel in the early hours of 7 October 2023.

Twelve months down the road, close to 50,000 Palestinians, mostly women and children, have been killed, with many more still to be recovered from underneath the rubble that has been amassing with every heavy Israeli raid on Gaza.

Over 100,000 Palestinians have been wounded, with many of them now suffering life-long injuries that are more often than not disabling. Gaza’s healthcare system, housing facilities, education system, and infrastructure are either devastated or badly damaged.

This has been the case despite the remarkable resilience of Hamas’s military wing, and the support it has received from Hezbollah in South Lebanon, whose rockets, fired at northern Israel, have put pressure on its military, and despite the recurrent international appeals for Israel to stop its genocidal war.

Emboldened by the failure of the international community to put a stop to his war on Gaza, and with the not-so-secret sympathy for his war on Hamas from several world capitals, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu took his assault on Hamas and Hezbollah to the next level with a series of assassinations of its leaders, including of Fuad Shukr, a leading Hezbollah figure in Beirut, and Ismail Haniyeh, the chief of the Hamas Political Bureau while he was in Tehran. Then there was the shocking elimination of Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah in Beirut on 27 September.

The killing of the Hamas and Hezbollah leaders and many of the fighters of both the Islamist resistance groups is part of the larger damage that both have suffered along with Israel’s destruction of significant parts of their military infrastructure, more so with Hamas in Gaza than with Hezbollah, at least so far, in South Lebanon.

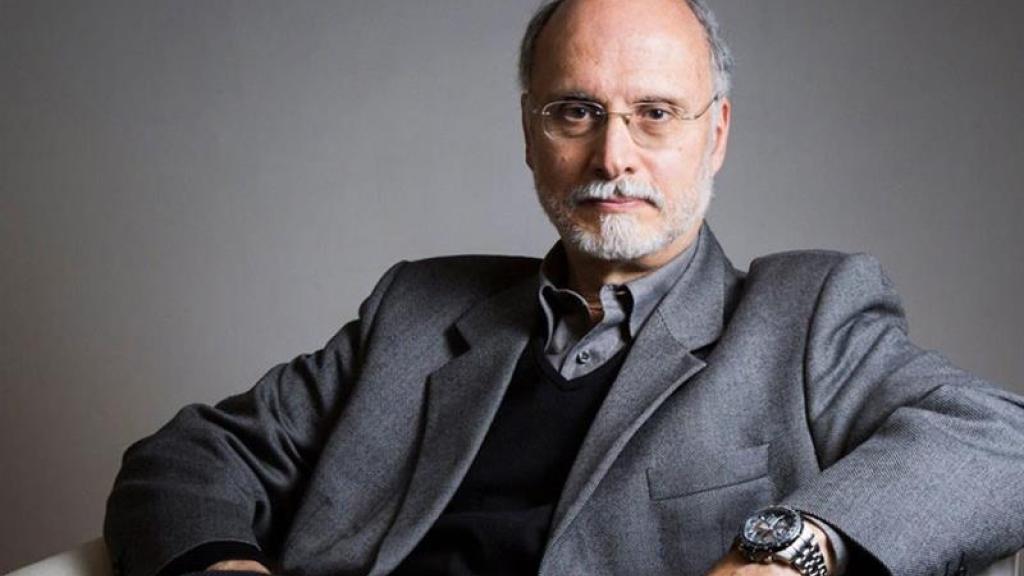

According to Gilbert Achcar, a Lebanese professor of Development Studies and International Relations at SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies), University of London, in the UK, the situation looks very difficult for Hamas.

Palestine

“We can say for sure that Hamas has been smashed in Gaza, and I don’t think that Israel will let them reconstitute their apparatus and the whole infrastructure that was built over decades,” Achcar said. Worse still, he added, he does not think that Israel is going to leave Gaza this time around.

“We have to remember that when [former Israeli Prime Minister Ariel] Sharon carried out his withdrawal from Gaza in 2005, Netanyahu, then a member of the Israeli Government, resigned to protest this withdrawal,” Achcar said. Today, Netanyahu is set to stay in Gaza, one way or the other, he said.

According to Achcar, “at best” Gaza will be like the West Bank in that it will be divided into tiny townships, similar to the situation in South Africa during the apartheid years when the black African population was forced into designated restricted neighbourhoods.

“Things will be much worse for Gaza given its geographic isolation,” Achcar said.

However, resistance, and militant resistance in particular, will not be fully eliminated. “It will persist, but more in occasional attacks as has been happening in the West Bank. For sure there is no going back [for Hamas] to the situation of 6 October 2023.”

Achcar said that it should not be overlooked that Hamas “remains strong” outside Gaza. “It is there in the West Bank, Jordan, and in the refugee camps in Lebanon,” he explained. He added that the question today is not about whether or not Hamas will remain, because “Hamas will remain simply because [Netanyahu] cannot eradicate it.”

The question is rather what Hamas will be able to do from now on.

For Achcar, the latter is the bigger question, especially in view of what he said is the fact that the “Palestinians in Gaza are realising more and more the level of their defeat.”

“This has really been a genocidal war along with an intensity in destruction that I don’t think can be compared to anything other than Hiroshima,” he said, in a reference to the 1945 US atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan during World War II.

“The far-right Israeli Government, which [in essence] is a group of neo-fascists and neo-Nazis, will surely push for the permanent reoccupation of Gaza,” Achcar said.

He argued that it is hard to ignore the consensus that has been created in Israeli political quarters about the need to fight hard against Hamas after the Al-Aqsa Flood Operation. “I think it is quite similar to the way things were in the US against Al-Qaida after the attacks of 9/11,” he said, in a reference to the bringing down of the World Trade Centre towers in New York and the attack on the Pentagon in the autumn of 2001.

“This is why I think that the overall balance sheet for the 7 October operation is disastrous and that it was a huge miscalculation,” he said. He added that with the current situation on the ground in Gaza and the damage that Hamas has been enduring, it will be very hard for its leaders to speak of “a divine victory” or any such thing in the near future.

Achcar argued that the situation is very hard in many ways, not just because of the damage that Hamas and the entire population of Gaza have suffered, but also because there is no clear political alternative to Hamas. “Today, there is simply a political vacuum there,” he stated, while arguing that the Palestinian Authority (PA) as a whole and its leader Mahmoud Abbas have “zero credibility” and “zero popularity” in Gaza.

According to Achcar, the prominent and popular Fatah leader Marwan Barghouti, imprisoned by Israel since 2002, arguably a leader of the Second Intifada in 2000, could have been a political alternative to Hamas. However, he added that “there is no way that Netanyahu will release Barghouti.”

Unfortunate and distressing as it might be, Achcar said, “this is a very hard moment [for the Palestinians]. It is a moment of defeat for the [Palestinian] liberation movement and a moment of victory for Zionist arrogance.”

“This much we have to realise,” he stated.

Achcar is not willing to entertain the argument that despite all the actual and long-term damage that the military might of the Israeli Occupation has inflicted on Hamas and Gaza, Hamas has also imposed a new reality in which Israeli arrogance was subject to a shocking challenge in the early hours of 7 October 2023 and that the PA narrative, which had been introduced along with the September 1993 Oslo Accords, about negotiations and security coordination with Israel as a path towards Palestinian statehood, has also been dramatically defied.

He argued that nobody needed to do anything to show that the Oslo Process has long been dead. It has been dead since the Second Intifada, he said.

Former Palestinian leader Yasser “Arafat had the illusion of [securing] an independent Palestinian state [through negotiations], but this illusion died with Arafat,” 20 years ago in November 2004, he said. He added that Netanyahu was not going to allow a Palestinian state, and that this much the Israeli Prime Minister has himself said.

However, he argued, that what the Al-Aqsa Flood had brought about was not the elimination of a faulty and inconclusive process of negotiations and security cooperation with Israel. What it did, he argued, “is introduce a much worse political alternative” than the status quo put together by the Oslo Process.

A year after the beginning of the Israeli war on Gaza, coupled by persisting Israeli military operations in the West Bank, the Palestinian population “is scattered in what is even less than a Bantustan,” and the Israeli far-right “is pushing to expel the Palestinian population into Sinai. They would have done so, had it not been for the red line that the Egyptian government drew about it.”

Today, he anticipates that Netanyahu’s far-right colleagues in government will push to keep the Palestinians in Gaza in Rafah at the very southern point of the Strip and allow Israeli settlers to reclaim large parts of Gaza in the north and maybe middle of the Strip right up to the borders with Egypt.

“The only silver lining in this whole catastrophe is the increase of [world] solidarity with the Palestinian [people and cause], especially in the US,” Achcar said. “This is important for the future. It is important that the world realise that some 50,000 people, mostly women and children, have been killed by Israel in Gaza.”

Meanwhile, he added that the Palestinian resistance does require a new political alternative that is different from the liberation movements of the past and not just from Hamas. “There has been a need for a third force, but the current forces have not been allowing” this new force to find its way, he said.

It has to be admitted that this new force should not be military, he added. He argued that military force will not secure Palestinian objectives, simply because of the discrepancy in favour of Israel. “When your enemy is stronger, don’t fight him on his terrain but find another way to fight him,” he said.

Achcar argued that he is not prescribing something that the Palestinian path to liberation is unfamiliar with. He said that “the biggest moment of Palestinian impact was during the First Intifada” in 1988, when the left-leaning Palestinian leadership of the uprising “had the intelligence not to use the weapons they had.”

At that point, Achcar said, the Israelis were caught off guard, and it was then that they decided to negotiate with the Palestinians in Oslo, simply to end the First Intifada, “which was then the peak of the Palestinian struggle.” Today, he added, the Palestinians could benefit from regaining the spirit of that moment, rather than try to resurrect the militant path.

The non-military struggle of the Palestinian people, Achcar argued, created a camp within Israeli society that was calling for Palestinian statehood. On the other hand, he argued that the path of suicide bombings helped Sharon to promote his extremist policies.

“Sharon surfed on Hamas suicide attacks,” Achcar said. He added that Sharon also trapped Hamas into this path in order to pursue his policies.

Today, Achcar said the Palestinians need a new approach in gaining their liberation and a new style of leadership that “is progressive” and will work on three objectives.

The first, he said, is to lead a good part of Israeli society to split from the ideology and path of Zionism. The second is for the new Palestinian leadership to connect with the civil-rights movements in the Arab world. The third is to expand and consolidate the international solidarity that has been on the rise due to the horrific Israeli war on Gaza.

Lebanon

Regarding Lebanon, however, the question of the future of the resistance is much more layered, according to Achcar. This question has become even more pressing with the assassination of Nasrallah.

Nasrallah and his political and military choices, Achcar argued, cannot be seen in black or white. He agreed that while some people might think of Nasrallah as the man who shored up the oppression of the Syrian people by supporting the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in Damascus, others might see him as the “sayyed al-mokkawama” (the head of resistance), who was arguably Israel’s worst nightmare for three consecutive decades.

During this period, he imposed defeats on the Israeli Army, including making it withdraw from the south of Lebanon in 2000 which it occupied since the 1982 invasion executed by Sharon, as chief of the Israeli military at the time.

“Nasrallah was [all of the above]; he meant different things to different people,” Achcar said.

“To his base in Lebanon, to his allies in the region, and to [many Shia], he was surely the sayyed al-mokkawama,” Achcar said. If one were to examine the reaction to the Israeli assassination of Nasrallah, one would find that the sense of devastation and loss was not confined to those who subscribed either to Nasrallah’s base or his ideology.

Many in Lebanon, he said, thought of Nasrallah and will continue to think of him as a “strong leader who imposed the Israeli evacuation and who dared to stand up to Israel.”

However, he added that it is hard today to think of Nasrallah without thinking of the fact that when he got involved in Syria, “he and Hezbollah were perceived as an Iranian proxy,” without excluding their role in forcing the Israeli evacuation of south Lebanon.

In the final analysis, Nasrallah’s dominant image is that of the man who forced the Israeli evacuation from south Lebanon, resisted the Israeli onslaught in 2006, and who over the past year has forced a large number of Israelis to leave their homes in the north of Israel on the borders with Lebanon as an act of solidarity with Gaza.

“This is why his assassination is a major victory for Israel, and this is why so many Lebanese, including myself, who stand clearly on the left and who disagree with much of the ideology of Hezbollah, found his assassination really saddening,” Achcar said.

He added that it is hard to think of Hezbollah as it has become, either in political or military terms, without thinking of Nasrallah. With close to 30 years at the helm, he argued, Nasrallah was the one who made Hezbollah the way it has become. He was arguably, “in relative terms, the best possible leader of Hezbollah, given that while he was willing to fight, he had the intelligence and sensitivity to preserve lives,” especially of civilians.

Achcar recalled the famous interview that Nasrallah gave after the Israeli war against Lebanon in July 2006 that came in the wake of Hezbollah’s abduction of Israeli soldiers. Nasrallah said that had he anticipated the huge damage that Israel would inflict on Lebanon, his calculations would have been different.

In August 2006, a few weeks after the end of war, Nasrallah said that had he known that Israel would inflict such a huge damage on Lebanon, he would not have ordered the kidnapping of two Israeli soldiers in an operation that Hezbollah fighters conducted during a secret crossing into the north of Israel.

This statement, Achcar said, was a message to the Lebanese people, “and Nasrallah had the courage and the conscience to make it.”

While he might not have been the major strategist that some people thought he was, during his years at the top of Hezbollah Nasrallah refrained from abducting or harming Israeli civilians because he did not want to subject Lebanese civilians to harm at the hands of Israel.

“This was part of his popularity… and this is why his death is a major loss for the country and not just for Hezbollah,” he added.

Such cautious and calculated political perceptions were perhaps shared with Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh “and this was one of the reasons why Netanyahu decided to assassinate these two leaders,” Achcar said.

Netanyahu did not want resistance leaders with political sensibility and with the courage and weight to pursue political settlements.

“Netanyahu is like Sharon,” Achcar said. Neither of these two men, he added, wanted or want to engage politically, and this is why Netanyahu does not want leaders with the ability or the intention to reach political settlements on any issue. He added that the replacement of Haniyeh with Yehiya Sinwar, who is much less inclined than his predecessor to consider pragmatic political compromises, is perhaps useful for Netanyahu’s on-going war against Hamas.

Speaking before the speculation over the Israeli assassination of Hashem Safieddine, the potential successor of Nasrallah, Achcar argued that whoever the replacement of Nasrallah might be as leader of Hezbollah, Israel is unlikely to have anything but an easier way ahead because it is unlikely that any of the potential successors will be able to deliver the kind of complex performances that Nasrallah did, no matter their flaws.

“I just don’t think that there will be another Nasrallah,” he stated. This is partially why the Lebanese resistance will also need to think of alternatives that are much more political, progressive, and inclusive and are less militant and sect-based, he added.

Israel

Not excluding the Israeli losses during its recently initiated ground operation in the south of Lebanon, Achcar argued that as a result of its year-long genocidal war on Gaza and the assassinations of the leaders of Hezbollah, Hamas, and commanders of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, Netanyahu can now claim he has managed to regain the Israeli deterrence that was compromised with the Al-Aqsa Flood Operation and, before it, by the performance of Hezbollah as it redeployed in southern Lebanon after 2006.

In the eyes of Netanyahu, Achcar argued, “the fear of Israel is there again.” He added that there are now concerns about the Israeli retaliation to the Iranian missile attacks on Israeli targets on 1 October.

Another emboldening fact for Netanyahu is that US President Joe Biden has been mostly supportive of the Israeli wars waged to destroy Hamas and Hezbollah. “Irrespective of whatever he has said when the world was outraged at the horrors of the war over the past year, the Israeli war on Gaza is arguably the first fully joint US-Israeli war,” Achcar said.

Consequently, he argued that Netanyahu, who is not sure that former Republican US President Donald Trump will find his way back to the White House in November, will not want to take the risk of waiting for the expiry of such US support in case Democratic Party nominee Kamala Harris wins the November elections.

“This is especially so with regards to Netanyahu’s plans against Iran. Netanyahu would not want to face the pressure for self-restraint that Harris might impose,” Achcar said. He added that Netanyahu will remember that former US President Barack Obama, “prioritised the nuclear deal with Tehran,” over Netanyahu’s strong objections.

A new Middle East?

Whatever might happen on the Iranian front, Achcar argued, today the political landscape of the Middle East is one where Islamist movements of all shades have suffered huge losses. With the retreat of these movements, he added, there is a political vacuum that needs to be filled with a new form of political power that could be similar to the “very impressive young civilian leadership” of the 2019 Sudanese Revolution that ousted the regime of former President Omar al-Bashir.

“This is not an easy thing to do, and it might take a long time before we get there,” he said.

Meanwhile, Achcar would not conclude that the Middle East is changing in the way that Netanyahu wants, where the resistance to Israeli occupation is forever defeated, or at least disabled, and where normalisation with Israel has become the norm, irrespective of whatever happens with the Palestinian cause.

This, he said, is not at all likely. “The Saudis themselves are now saying that they will not normalise with Israel prior to a serious move towards Palestinian statehood.

Other factors that might prevent the emergence of the kind of Middle East that Netanyahu is hoping for, Achcar said, include the popular support in the region for the rights of the Palestinian people and the growing international support that is unlikely to be silenced by a limited Israeli military withdrawal from Gaza.