Age of ‘Empire’ or age of imperialism? A reply to Claudio Katz

There has been a notable rise in debate among Marxists about the theory of imperialism in the past few years. This has included an ongoing exchange between Argentine economist Claudio Katz and myself.1

A few weeks ago, Katz, one of best-known progressive economists in Latin America, published another contribution outlining his analysis of contemporary imperialism and some strategies for resistance. His essay is divided into three parts: a positive outline of his views; a critique of the Leninist position (mostly directed against my previous replies); and a polemic mainly directed against the ideas of Rolando Astarita, another Argentine economist who wrongly believes national oppression and imperialist super-exploitation have lost their relevance.2

As this is my third reply, I will refrain as much as possible from repeating arguments in previous contributions. Instead, I will focus on certain theoretical issues I consider particularly important and questions of anti-imperialist strategy.

Katz’s view of the US-led Empire

Katz claims that capitalism is no longer characterised by contradictions between imperialist powers but rather by domination of a single (US-led) “Empire”. In contrast, I defend the analysis elaborated by Vladimir Lenin, according to which the capitalist world continues to be characterised by inter-imperialist rivalry, currently expressed in the tensions between Western and Eastern Great Powers (US, Western Europe and Japan versus China and Russia).

Katz continues to uphold his thesis of “Empire” and repeats arguments outlined in previous contributions. Likewise, I continue to consider his “Empire” theory as flawed. This does not mean I disagree with all his arguments. I basically agree with his critique of Astarita’s theses, and as an anti-imperialist Marxist I share his opposition to Western imperialism and take the side of oppressed peoples.

My disagreements with Katz are rooted in the fact that he is a one-sided anti-imperialist. For him, “the main enemy … is the American leadership of the imperial system”. Katz explicitly refuses to recognise the imperialist character of Russia and China. Consequently, he is anti-imperialist against the US and its allies, but not against other imperialist powers such as Russia and China. As such, he does not support the struggles of oppressed peoples against these Eastern Great Powers and their local allies.

Katz claims his concept is based on Lenin’s theory but that it takes into account “two great changes” that occurred “during the second half of the 20th century.”

On one hand, a bloc of countries was formed which divorced from the capitalist market (the so-called socialist camp), and on the other hand, the transformation of classical imperialism into an imperial system was consummated.

According to the Argentine economist:

The imperial system modified the militarist rivalry between the main colossi of capitalism. The bloody confrontations between France and Germany or Japan and the United States were replaced by an apparatus commanded by the Pentagon that protects the powerful. The American giant acts as the center of a stratified and pyramidal mechanism, which articulates different types of relations between the first power and its partners. This configuration operates with norms of belonging, coexistence and exclusion, which define the role of each region in global geopolitics.

While Katz acknowledges Russia and China’s rise as new powers, he not only denies Russia’s imperialist character but even the idea that China has become a capitalist country:

In the 21st century, this adaptation of the Leninist approach faces another context. The implosion of the USSR was followed by the disappearance of the so-called socialist camp and the consolidation of capitalism in Russia, which led to the new centrality of a harassing and harassed power. Moscow is harassed by NATO and implements external incursions in its radius of influence. For this reason, it acts as a non-hegemonic empire in the making. It develops its priorities in conflict with the imperial system, but with actions that guarantee by force the primacy of its interests.

China has been placed, like Russia, outside the imperial system and endures the same aggressions from the Pentagon. But unlike its Eurasian counterpart, it has not completed the capitalist restoration and has so far avoided all the misdeeds of an imperialist power. It does not send troops abroad, avoids involvement in military conflicts and maintains great geopolitical prudence. With this defensive strategy it reinforces its relations of economic domination with the bulk of the periphery.

‘Empire’: An un-Marxist myth hovering over the contradictions between classes and states

I have shown in previous replies (as well as in other works) that China became capitalist three decades ago. Any concrete analysis of China’s economy reveals that its corporations (including state-owned ones) operate according to the capitalist law of value, make profit, etc. I have provided numerous facts and statistics to prove this. In contrast, Katz exercises great restraint in providing any concrete evidence for his theses.3

Likewise, Katz limits his response to my analysis of Russian imperialism to explaining that since Moscow is in confrontation with the “Empire”, it can not be imperialist. It is merely a “non-hegemonic empire in the making. It develops its priorities in conflict with the imperial system, but with actions that guarantee by force the primacy of its interests.” For him, being imperialist and not being part of the US-led “Empire” is a contradiction in terms.4

A general feature of Katz’s works on imperialism is that he limits his arguments mostly to the sphere of the doctrinaire generalities of structuralism — an unfortunate hit export of “Marxist” academics from French universities who view history as a process without subjects. Lenin once noted this theory is a “narrow objectivism … that describes the process in general, and not each of the antagonistic classes whose conflict makes up the process.”5Consequently, structuralism — and Katz’s works bear its earmarks — get along pretty fine without facts and a concrete analysis of reality.

I want to focus on the theoretical fundament of Katz’s thesis of US-led “Empire”. He claims to have elaborated Lenin’s theory of imperialism according to changes in capitalism since World War II. Instead, he is liquidating Lenin’s theory and turning the Marxist method on its head.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels started their analysis of world politics from the contradictions between the classes and nations, between states and powers. Consequently, Bolshevik theoreticians viewed imperialism as a contradictory global system based on antagonisms between classes, nations and states. They assessed the political and economic strength of individual powers and their relations with each other and derived from this a characterisation of the world situation.

I consider modern capitalism as characterised by several lines of fundamental contradictions which are, of course, closely intertwined:6

i) antagonism between classes;

ii) antagonism between oppressor and oppressed nations;

iii) antagonism between imperialist powers and semi-colonial countries; and

iv) antagonism between states in general and imperialist powers in particular.

Katz has a completely different approach. He starts with the dogma of the US-led “Empire”, without any concrete analysis, and derives his assessment of individual states and popular movements in various countries from their respective position towards such “Empire”.

Lenin considered imperialism as a system that arises from the economic fundament of capitalism and its class contradictions. Imperialism, including any “Empire” was not detached from the economic basis. When the Bolsheviks discussed a new program in 1917-19, Lenin strongly opposed the proposal of Nikolai Bukharin and Georgy Pyatakov — Lenin repeatedly polemicised against their “imperialist economism” (Katz refers to this in replying to Astarita) — to delete without substitution that part of old program dealing with the fundamental contradictions of capitalism.7

Lenin noted in his conspectus of Hegel’s Science of Logic: “Thought proceeding from the concrete to the abstract — provided it is correct … — does not get away from the truth but comes closer to it.”8But Katz does the opposite: he starts with an abstract dogma and subordinates classes and nations, and their contradictions and struggles, to such dogma. This makes his whole scheme pretty unmaterialistic and idealist — that is, un-Marxist.

If Russia intervenes with its troops in other countries to expand its influence, put down popular rebellions or keep an allied dictatorship in power (for example in Chechnya, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Syria, Libya, Mali, etc.), it is not imperialist because … Moscow is not part of the US-led “Empire”.

If China develops economic and financial relationships with semi-colonial countries that result in extracting surplus-value from local workers and peasants, it does not constitute imperialist super-exploitation because … Beijing is not part of the US-led “Empire”.

Katz has the opposite view to Lenin. He starts with the top of the political superstructure — the supposed US-led “Empire” — and subordinates all struggles between classes and states to this single feature. It is not the relationship between classes and nations that counts for Katz, but rather the relationship of classes and nations around the globe to the US-led “Empire”. He creates an un-Marxist myth that hovers over the contradictions between classes and states. Katz replaces Lenin’s concept of imperialism as a political-economic analysis with a purely political and one-sided theory that is consequently without any materialist dialectic.

Turning Lenin on its head: Katz’s idealist conception of ‘imperialism’ as aggressive foreign policy

The Marxist theory of imperialism, as elaborated by Lenin, Bukharin, Rosa Luxemburg, and Rudolf Hilferding in the early 20th century, was based on an economic analysis of capitalism. They identified monopolisation — the process of formation of monopolies in the industrial and financial sector — as the economic fundament of imperialism. Lenin stressed this repeatedly: Here we have what is most essential in the theoretical appraisal of the latest phase of capitalism, i.e., imperialism, namely, that capitalism becomes monopoly capitalism.9

The formation of imperialist powers — some long-time Great Powers (such as Britain, France and Russia), other newly emerging (for example Germany, US and Japan) — inevitably took place in relation to this economic process of monopolisation. Hence, “…an essential feature of imperialism is the rivalry between several great powers in the striving for hegemony…”10

The Bolshevik party leader summarised the characteristics of the imperialistic epoch as follows:

We have to begin with as precise and full a definition of imperialism as possible. Imperialism is a specific historical stage of capitalism. Its specific character is threefold: imperialism is monopoly capitalism; parasitic, or decaying capitalism; moribund capitalism. The supplanting of free competition by monopoly is the fundamental economic feature, the quintessence of imperialism. Monopoly manifests itself in five principal forms: (1) cartels, syndicates and trusts — the concentration of production has reached a degree which gives rise to these monopolistic associations of capitalists; (2) the monopolistic position of the big banks — three, four or five giant banks manipulate the whole economic life of America, France, Germany; (3) seizure of the sources of raw material by the trusts and the financial oligarchy (finance capital is monopoly industrial capital merged with bank capital); (4) the (economic) partition of the world by the international cartels has begun. There are already over one hundred such international cartels, which command the entire world market and divide it “amicably” among themselves — until war redivides it. The export of capital, as distinct from the export of commodities under non-monopoly capitalism, is a highly characteristic phenomenon and is closely linked with the economic and territorial-political partition of the world; (5) the territorial partition of the world (colonies) is completed.11

Katz ignores the economic process of monopolisation in the world economy. The fact China has as many corporations and billionaires as the US, or that Russia’s economy is dominated by domestic monopolies that export capital to other countries are irrelevant for our critic.

How does he justify this? By reformulating the Marxist theory of imperialism. Katz eliminates the economy from his analysis of imperialism and limits it to aggressive and militarist foreign policy. This key aspect of Katz’s theory of imperialism is pretty evident in his latest essay.

He writes:

The place of these powers [China and Russia] in the world economy does not clarify their role as an empire. This role is elucidated by evaluating their foreign policy, their foreign intervention and their geopolitical-military actions on the global stage. This record allows us to update Lenin's view, avoiding the repetition of his diagnoses, in a radically different context from that prevailing at the beginning of the last century.

Likewise, while forced to admit China’s economic strength in the world market, he claims this does not make it an imperialist power:

But this view ignores the basic difference that distinguishes an imperial enemy from an economic dominator. The United States exercises oppression in all areas, while its rival profits from the benefits of unequal exchange, the transfer of value and the capture of rents. These two adversities are not equivalent for Latin America because the first makes any sovereign action impossible and the second obstructs development. They operate, therefore, as limitations of different magnitude.

For Katz, an “economic dominator” (such as China) that exploits other countries is not necessarily an imperialist power. Such a view is consistent with Katz divorcing politics from economy, but completely inconsistent with the Marxist theory of imperialism. Lenin denounced such an approach, which was characteristic of Katz’s ideological progenitor, Karl Kautsky:

Advancing this definition of imperialism brings us into complete contradiction to K. Kautsky, who refuses to regard imperialism as a “phase of capitalism” and defines it as a policy “preferred” by finance capital, a tendency of “industrial” countries to annex “agrarian” countries. Kautsky’s definition is thoroughly false from the theoretical standpoint. What distinguishes imperialism is the rule not of industrial capital, but of finance capital, the striving to annex not agrarian countries, particularly, but every kind of country. Kautsky divorces imperialist politics from imperialist economics, he divorces monopoly in politics from monopoly in economics in order to pave the way for his vulgar bourgeois reformism, such as “disarmament”, “ultra-imperialism” and similar nonsense. The whole purpose and significance of this theoretical falsity is to obscure the most profound contradictions of imperialism and thus justify the theory of “unity” with the apologists of imperialism, the outright social-chauvinists and opportunists.“ 12

Katz considers China as not imperialist because it does not wage wars in other countries (yet). But military aggression is only one form of imperialist policy; “peaceful” penetration and economic dependency is another — one which plays a much larger role. In fact, military intervention has been the exception in imperialist foreign policy in the past decades, taking place only in a few countries. In contrast, economic penetration and dependency by imperialist monopolies takes place every single day. This is even more the case since one of the important changes in the imperialist system has been the process of de-colonisation, which transformed nearly all colonies (Africa, large parts of Asia, Eastern Europe) into capitalist semi-colonies. With the disappearance of colonies, the need for regular military interventions and permanent deployment of troops to uphold occupation also diminished. For these reasons, China’s methods of “indirect”, economic subjugation of peoples in the South via financial means is a typical instrument for 21st century imperialism.

Lenin’s description of this process sounds pretty accurate when it comes to the relationship between Western powers and China with semi-colonial countries:

Economically, imperialism is monopoly capitalism. To acquire full monopoly, all competition must be eliminated, and not only on the home market (of the given state), but also on foreign markets, in the whole world. Is it economically possible, “in the era of finance capital”, to eliminate competition even in a foreign state? Certainly it is. It is done through a rival’s financial dependence and acquisition of his sources of raw materials and eventually of all his enterprises.13

In contrast, Katz advocates an idealist conception of “imperialism” as aggressive foreign policy, leaving out the economy — the material basis of capitalism. Consistent with such a reinterpretation of imperialism, Katz does not consider imperialism as a specific stage of capitalist development — its age of monopolisation — but rather as aggressive foreign policy, which has always existed in capitalism. In his view “imperialism … has been present since the beginning of capitalism.“

Are the BRICS+ in a position to challenge the ‘Empire’?

In previous replies, I demonstrated that the idea of a US-led “Empire” that dominates the world does not correspond to the reality of 21st century capitalism. There is no need to reproduce this argument, but it does make sense to briefly deal with developments since my last reply to Katz.

In the past two years, there have not only been two big wars — in Gaza and Ukraine — but also a substantial expansion of the China and Russia-led BRICS alliance. At the beginning of 2024, four states (Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran and United Arab Emirates) formally joined the five original members (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). Saudi Arabia has been invited to join, but has not decided on this. In October 2024, 13 other states became so-called “partner countries” (Algeria, Belarus, Bolivia, Cuba, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Nigeria, Thailand, Türkiye, Uganda, Uzbekistan, and Vietnam).

This alliance is not a homogenous and centralized bloc. Several states have conflicts with each other. Some have closer and others less closer relations with Western powers. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Russian president Vladimir Putin are not wrong in saying BRICS “is not an anti-western group, it is a non-western group.” But despite such formal claims, the Eastern-dominated alliance is objectively the strongest political, economic and military rival to Western powers, and is seen as such by them.14

Indeed, they have reasons to fear the BRICS+ alliance. Most importantly, China has become the first or second largest power in terms of economic output, industrial production and trade. Russia and China are the second and third largest military powers. Albeit the alliance is not a monolithic bloc, the fact that dozens of countries have shown interest in joining demonstrates the two Eastern powers are greatly expanding their spheres of influence.

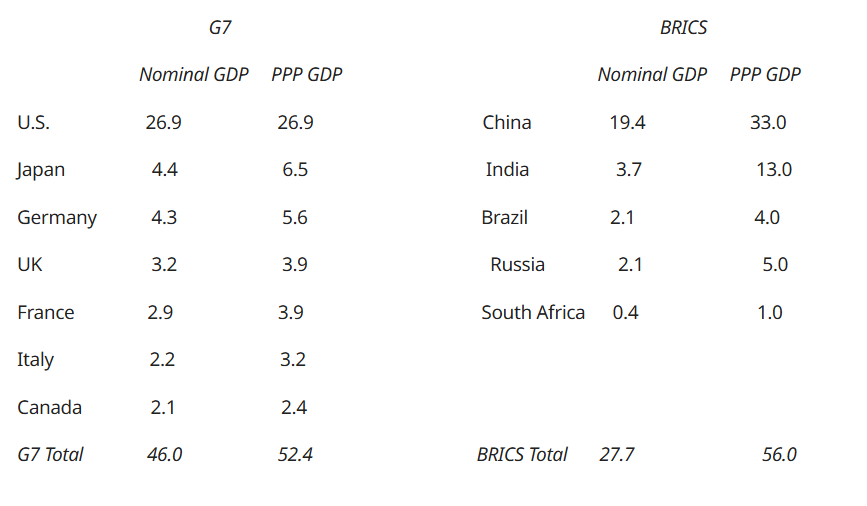

There is a significant difference in calculating the size of the two blocs, depending on the measures of calculation. Nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is measured in US dollar terms, with market-rate currency conversion, while Purchasing Power Parity (PPP)-adjusted GDP uses international dollars (with the US as the base country for calculations). The latter better accounts for cost of living and inflation. In nominal terms, the G7 — the Western imperialist alliance — still has a larger economic output. But calculated in PPP terms, BRICS+ has surpassed Western powers. The figures below are for the original five BRICS+ member states, before the alliances expanded to incorporate four additional member states and 13 partner countries.

Table 1. Nominal GDP and PPP GDP of G7 and BRICS (original 5 states) in trillion US-Dollar, 202315

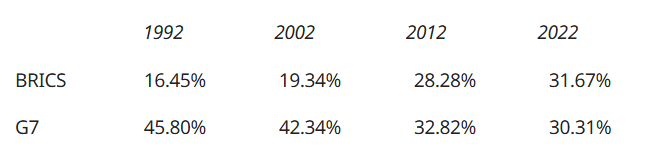

In any case, there is no doubt that the BRICS states have much higher growth rates and are in the process of catching up, or even surpassing, the “old” imperialists. (See Table 2)

Table 2. Share of G7 and BRICS (original 5 states) in Global GDP, 1992-2022 (PPP-adjusted)16

BRICS’ growing clout is evident by various other indicators. In expanding to nine member states, its combined population grew to about 3.5 billion, or 45% of the world’s population. In terms of energy sources, BRICS+ members own 47% of the world’s oil reserves and 50% of natural gas reserves.17As of 2024, BRICS+ control about 72% of the world’s rare earth metal reserves.18

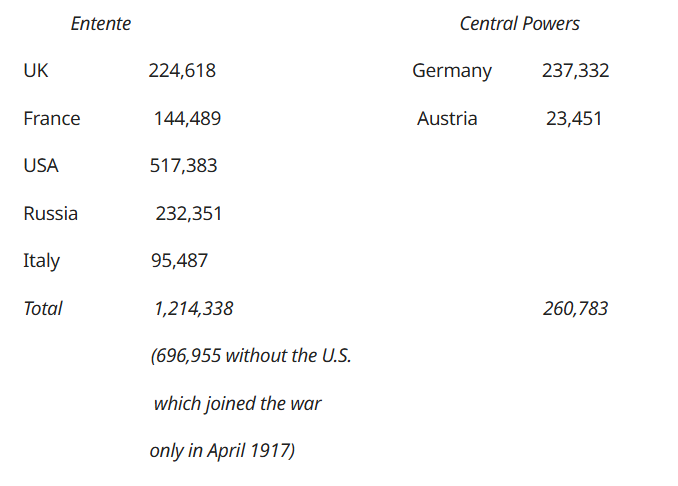

It is not without interest to make a historical comparison with the relation of forces between imperialist blocs at the onset of World War I and II. In the three tables below, we can see that the two rivalling alliances were not equal in terms of economic output, but that the Western-led imperialist bloc was clearly stronger. Before the start of World War I, the Entente powers had a combined output of more than four times that of the Germany-led bloc (See Table 3). I am aware that the list of countries in this table is not complete, as Japan (which briefly joined the Entente) and the Ottoman Empire (which sided with Germany) are missing. However, both were rather small powers in terms of economic output and would not significantly alter the total relation of forces between the blocs.

Table 3. GDP of imperialist powers, 1913 (million 1990 international $)19

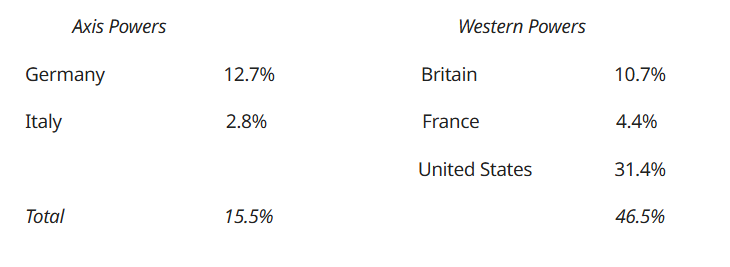

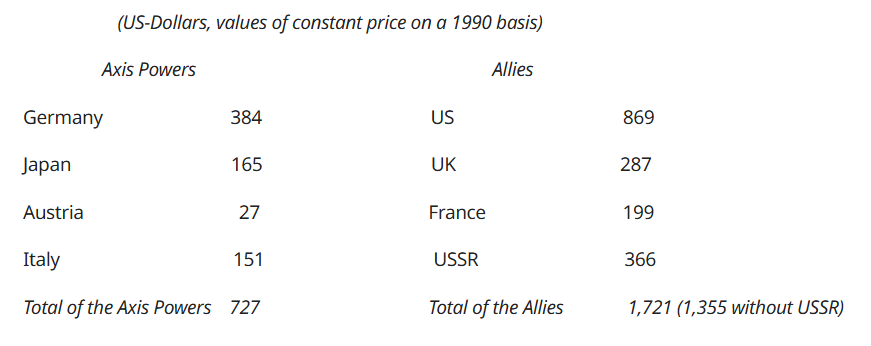

We see a similar picture before the start of World War II. Western powers (which were joined by the USSR in 1941) were two or three times stronger that the Axis Powers. (See Table 4 and 5)

Table 4. Imperialist powers’ share of world manufacturing output in 193820

Table 5. Gross National Product of major powers participating in WWII in 193921

This overview of the relation of forces between the US-led bloc and the China/Russia-led bloc demonstrates that the so-called “Empire” is clearly no longer in a position to dominate the world. True, its military (in terms of foreign bases and expenditure) is much larger than its rivals. However, the past two decades have shown that the US’s decline is taking place not only in economic but in political-military terms. Think about Washington’s defeats in Iraq and Afghanistan. Think about its failure to seriously damage Russia’s economy despite the unprecedented regime of sanctions after Putin invaded Ukraine in February 2022. Think about the embarrassing isolation of the US and Israel in the United Nations General Assembly on the issue of Palestine.

That China and Russia have succeeded in creating an alliance that encompasses half of humanity and a significant part of the world economy demonstrates that the US-led “Empire” is far from imposing its will on the world.

Furthermore, as the situations before World War I and II show, it is wrong to conclude that the superiority of one imperialist camp means that the other is not imperialist.

Why have there been no wars between imperialist powers since 1945?

Katz challenges my critique of his “Empire” thesis by asking why the US-led bloc has existed for so long without significant inner tensions. He writes that I “ignore the monumental changes that separate the classic era of imperialism from the postwar period and the 21st century.”

The first period was marked by wars between empires and in the second such conflagrations have not taken place… The current system with total primacy of the United States over Europe and Japan has eliminated the possibility of wars between these components of the triad. This fact introduces a qualitative shift in the dynamics of imperialism.”

He also adds:

There is intense competition between German and Japanese companies and their American counterparts, but the Pentagon keeps its sights set on Moscow or Beijing and does not worry about Berlin or Tokyo. … What explains why this German-Japanese development — much more intense than Russia and longer-standing than China — did not lead to military tensions with the first power [the US], is the integration of the two allies of the West in NATO, that is, their membership in the imperial system.

In fact, the long-lasting collaboration between the US and its Western allies is not based on a supposed qualitative transformation of imperialism but on concrete and temporary historical conditions. The US’ hegemonic role within the capitalist world was the result of the outcome of World War II, where other imperialist powers were either defeated (Germany and Japan) or became allies in a subordinated position (Britain and France). Washington’s domination was reinforced by the fact that imperialist states had no alternative but to accept US leadership to wage their Cold War against the Stalinist states. Inter-imperialist rivalry was overdetermined by another contradiction — that between Western powers and the USSR-led camp of Stalinist states.

After the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, the US became the absolute world hegemon for a short period until its domination began to decline in the 2000s. The 2008 Great Recession was a turning point because, from then on, Russia and China emerged as new imperialist powers. Since then, a new inter-imperialist rivalry has overdetermined the old rivalry between Western powers.

Katz claims the Pentagon simply controls the “Empire” and subjugates other Western powers. I argue that because of specific historic conditions, Western Powers pursued their respective imperialist interests by aligning themselves with Washington. But this did not result in the creation of an integrated “Empire” under the single command of the Pentagon. Rather, it resulted in the creation of an alliance of imperialist states, among which the US is the strongest. This alliance is currently held together by the rise of imperialist rivals in the East.

However, this does not mean that tensions between Western imperialist powers have disappeared. We saw open tensions during US President Donald Trump’s first term, and will most likely see more of these during his incoming second term. Will this result in open warfare between Western powers? Certainly not in the foreseeable future. However, it is far from guaranteed that the European Union will remain closely allied with Washington. Likewise, it is an open question whether it will continue to exist in its present composition or split, with one camp staying with the US and another taking an independent position.

However, all this is not decisive for our discussion. Our main argument against Katz’s thesis of a US-led Empire is that the world situation is marked by the existence of several imperialist Great Powers, of which some are in accelerating rivalry against each other while others are in alliance. This has been the case since the end of the first decade of the 21st century and will stay like this for the coming period. Furthermore, given the decline of the capitalist system, contradictions between imperialist powers will inevitably accelerate and place the danger of World War III on the agenda.22

Was Lenin’s program of anti-imperialism only fit for revolutionary situations?

Katz claims Lenin’s policy of defeatism against all imperialist powers is a program that applies only for revolutionary situations and that since no such situation exists today, Lenin’s anti-imperialist program no longer applies:

Lenin based his anti-imperialist strategy on three diagnoses: terminal crisis of capitalism, intense generalization of wars between the main powers and imminence of the socialist revolution. All the orientations that he proposed of rejection of the war conflagration through defeatism and the creation of anti-imperialist fronts in the periphery, were based on that evaluation.

Our critics … repeat the Bolshevik leader's revolutionary strategy of defeatism, which emphasized the shared guilt of all the powers in the war. But they omit that this characterization was framed in the context of imminent socialist revolution, absent today.

But Lenin’s program was not based on a conjunctural assessment that did not apply for a non-revolutionary situation. It was rooted in the character of the epoch of capitalism in its last stage. He differentiated between the epochs of the 19th century (the epoch of rising capitalism) and the epoch of monopoly capitalism, which opened at the start of the 20th century. In the former epoch, it was legitimate for socialists to side with one power against another, but this is no longer the case for the imperialist epoch.

In a polemic against reformist Menshevik Alexander Potresov, who justified defence of the imperialist fatherland by referring to Marx taking the side of a European power against another in 19th-century wars, Lenin emphasised the fundamental difference between the epoch of rising capitalism and the epoch of imperialism.

In 1859, it was not imperialism that comprised the objective content of the historical process in continental Europe, but national-bourgeois movements for liberation. The mainspring was the movement of the bourgeoisie against the feudal and absolutist forces. Fifty-five years later, when the place of the old and reactionary feudal lords has been taken by the not unsimilar finance capital tycoons of the decrepit bourgeoisie, the knowledgeable Potresov is out to appraise international conflicts from the standpoint of the bourgeoisie, not of the new class… Let us suppose that two countries are at war in the epoch of bourgeois, national-liberation movements. Which country should we wish success to from the standpoint of present-day democracy? Obviously, to that country whose success will give a greater impetus to the bourgeoisie’s liberation movement, make its development more speedy, and undermine feudalism the more decisively. Let us further suppose that the determining feature of the objective historical situation has changed, and that the place of capital striving for national liberation has been taken by international, reactionary and imperialist finance capital. The former country, let us say, possesses three-fourths of Africa, whereas the latter possesses one-fourth. A repartition of Africa is the objective content of their war. To which side should we wish success? It would be absurd to state the problem in its previous form, since we do not possess the old criteria of appraisal: there is neither a bourgeois liberation movement running into decades, nor a long process of the decay of feudalism. It is not the business of present-day democracy either to help the former country to assert its “right” to three-fourths of Africa, or to help the latter country (even if it is developing economically more rapidly than the former) to take over those three-fourths.23

Marxists based their intransigent opposition against all Great Powers not on the hope of an “imminent socialist revolution” but on their fundamental assessment of the epoch of imperialism in which the bourgeoisie in all imperialist states have assumed a reactionary character.

US-led ‘Empire’ and Russian Tsarism — a wrong analogy

Katz’s misinterpretation of Lenin’s reasoning for his defeatist program goes hand-in-hand with his repeated reference to Marx’s strategy in the 1848 revolution and thereafter, in which he identified Tsarist Russia — the strongest remaining bastion of feudalism — as the main enemy. Katz writes for example:

The American colossus currently occupies a place similar to that of old Tsarist Russia, as a political bastion of world reaction.

Our approach precisely highlights the current similarities with the 19th century due to the centrality of the main enemy. The place that Russia had in Marx's time is currently occupied by the United States. Critics accept the validity of this location two centuries ago, but do not endorse it for the current context. They consider that Lenin's theses erected an irreversible border between both stages.

In my second reply I demonstrated that such an analogy is fundamentally wrong. However, since Katz repeats this analogy several times in his new essay, I feel obliged to add some arguments.

Katz’s analogy is inappropriate because we do not live in a US-dominated unipolar world and it is the dictatorships of Putin and Xi Jinping that resemble the Tsarist autocracy more than the US. But this analogy is also mistaken because it is deeply unhistoric, as it is based on turning back the wheels of time. It applies an approach to states and wars that was justified in the epoch of transition from feudalism to capitalism in the 19th century to the current epoch of decaying capitalism.

The Bolsheviks rejected such an approach as it violates the laws of historical materialism. In the epoch of transition from feudalism to capitalism (that of rising capitalism), the bourgeoisie could play a progressive role in the struggle against the old order of the Middle Ages. In the current epoch of transition from capitalism to socialism, this is no longer the case. In this period, the bourgeoisies of imperialist powers play a reactionary role — without exception.

Katz’s reference to the foreign policy of Marx and Engels in the 19th century, and their focus on the struggle against Russia, was also used by social-chauvinists in various countries during World War I — from Kautsky, Heinrich Cunov to Georgi Plekhanov and Pavel Axelrod — to justify their defence of the imperialist fatherland.

Lenin strongly rejected such an analogy because it applies the program of a bygone era to wars in the imperialist epoch. He stressed socialists have to oppose all Great Powers, irrespective of if they are stronger or weaker, older or younger:

Let us suppose that two countries are at war in the epoch of bourgeois, national-liberation movements. Which country should we wish success to from the standpoint of present-day democracy? [As this article was written for a legal publication in Tsarist Russia, the Bolsheviks often used the synonym “present-day democracy” for “socialist proletariat”.] Obviously, to that country whose success will give a greater impetus to the bourgeoisie’s liberation movement, make its development more speedy, and undermine feudalism the more decisively. Let us further suppose that the determining feature of the objective historical situation has changed, and that the place of capital striving for national liberation has been taken by international, reactionary and imperialist finance capital. The former country, let us say, possesses three-fourths of Africa, whereas the latter possesses one-fourth. A repartition of Africa is the objective content of their war. To which side should we wish success? It would be absurd to state the problem in its previous form, since we do not possess the old criteria of appraisal: there is neither a bourgeois liberation movement running into decades, nor a long process of the decay of feudalism. It is not the business of present-day democracy either to help the former country to assert its “right” to three-fourths of Africa, or to help the latter country (even if it is developing economically more rapidly than the former) to take over those three-fourths.24

Katz wants to ahistorically transmit the legitimate tactics of the struggle against feudalism — of which Tsarist Russia constituted the most powerful force in the time of Marx and Engels — to the imperialist epoch, in which all Great Powers play a reactionary role.

… the general feature of the epoch, however, was the progressiveness of the bourgeoisie, i.e., its unresolved and uncompleted struggle against feudalism. It was perfectly natural for the elements of present-day democracy, and for Marx as their representative, to have been guided at the time by the unquestionable principle of support for the progressive bourgeoisie (i.e., capable of waging a struggle) against feudalism, and for them to be dealing with the problem as to “the success of which side”, i.e., of which bourgeoisie, was more desirable.25

Gregory Zinoviev, Lenin’s closest collaborator for a long time, pushed the same argument in his book The War and the Crisis in Socialism, written in 1915-16:

In the epoch when the question of the conquest of power by the bourgeoisie, the victory of the bourgeoisie over the remnants of feudalism, was on the agenda, Marx and Engels during the wars advocated the victory of this or that bourgeoisie, depending on which victory was most favorable for democracy and socialism. 26

We can also formulate our methodological objection against Katz from a different angle. Katz advocates a model (fighting against a single “main enemy” among the Great Powers) that was legitimate in an epoch of rapidly growing productive forces in which the decisive task was to break down the narrow barriers of feudalism and fight against forces that could endanger such historic progress. But such a model is inapplicable for an epoch of stagnating productive forces, climate catastrophe, economic depression and war. In such an epoch, all imperialist bourgeoisies can only be reactionary and obstacles for the progress of humanity:

The present war is imperialist in character. This war is the outcome of conditions in an epoch in which capitalism has reached the highest stage in its development; in which the greatest significance attaches, not only to the export of commodities, but also to the export of capital; an epoch in which the cartelisation of production and the internationalization of economic life have assumed impressive proportions, colonial policies have brought about the almost complete partition of the globe, world capitalism’s productive forces have outgrown the limited boundaries of national and state divisions, and the objective conditions are perfectly ripe for socialism to be achieved.27

For all these reasons, Katz’s attempt to turn back the wheels of time and advocate tactics in the struggle against feudalism for the epoch of struggle against imperialism are a gross violation of historical materialism. Politically, it represents a distortion of Marxism into an ideology of collaboration with Chinese and Russian imperialism.

Staying neutral or siding with reaction in important popular struggles?

Our differences with Katz are not limited to the sphere of analysis and theory, as they have profound consequences for socialist strategy and practical intervention in the class struggle. As Katz knows only one enemy — the US-led “Empire” — he characterises wars of national defence and popular rebellions by only one criterion: are they directed against Washington and its allies or against the rivals of the “Empire”. While he advocates support for the former type of struggles, he refrains from supporting the latter or even sharply denounces these.

This is evident from various statements in his essay. While he does not endorse Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, he certainly does not side with the people under attack. He does not defend Ukraine because he views it merely as a proxy of the US-led “Empire”:

The United States was also the promotor of the war in Ukraine. It tried to add Kyiv to the NATO missile network surrounding Russia, in order to affect its rival's defensive structure. With this objective, it promoted the Maidan revolt, encouraged nationalism against Moscow and supported the mini-war in Donbass. It sought to trap its adversary in a conflict aimed at imposing the rearmament agenda on Europe.

It seems Katz does not know about the long-time national oppression of Ukraine by Great Russian imperialism, about Russian monopolies, about Ukraine’s desire for independence, etc. All this is foreign to Katz because he does not recognise “smaller people” (we put this in quote marks since Ukraine’s population has more or less the same size as Argentina’s) as political subjects. For him, they can only be proxies of Great Powers. This is even more the case if such “smaller people” fight against oppression by rivals of the US-led “Empire”:

The Pentagon is the main promoter, responsible for and cause of the greatest tragedies of recent decades. The United States carried out a harrowing intervention in the Greater Middle East to control oil, crush rebellions and subdue rivals. From there, it commanded the bloodshed of the Arab Spring, facilitated jihadist terrorism and perpetrated the demolition of four states (Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan and Syria)… The destruction of Yugoslavia, the fracture of African countries and the appearance of mini-States controlled by NATO illustrate this regression.

As a matter of fact, the Great Arab Revolution was directed against all kinds of capitalist dictatorships — those aligned against the US (for example Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain, Yemen) as well as those aligned with Russia and China (Libya and Syria). This was first and foremost a spontaneous democratic revolution that was often slaughtered by reactionary tyrannies with support from US and Russian imperialism (Egypt and Bahrain; Syria). US military intervention was much shorter and more limited in Libya in 2011 than Russia’s in Syria since 2015. Washington’s intervention in East Syria to defeat Daesh did not contribute in any way to the liberation struggle against Assad.

As we have already shown in our previous reply, the formulation “destruction of Yugoslavia” reflects Katz’s opposition to the struggle of the non-Serbian people for national self-determination (which is why he shamefully characterized the “ghostly republic of Kosova” as an “old Serbian province”). I assume that his protest against the “fracture of African countries” reflects his denial of existing national and ethnic oppression in various states on the continent against which people have risen up. We can not refrain from commenting that such adaption to chauvinism against popular liberation struggles usually reflects an ideological mindset typical of supporters of pro-Russian social-imperialism.

The program of one-eyed anti-imperialism

Katz essentially advocates a program that can only be characterised as one-eyed anti-imperialism. Since there is only one “main enemy” — the US-led “Empire” — all other Great Powers are at least lesser evils. We are fully aware that Katz is critical of Putin’s foreign policy. Likewise, he recognises China’s foreign investments and loans are aimed not at the betterment of humanity but for higher profits for its monopolies. But since Russia is supposedly forced to defend itself against NATO expansion and “China avoids imperial arrogance”, these Eastern powers are the lesser evil.

Hence, Katz wants to focus the anti-imperialist struggle against the US-led “Empire”. He criticises the program we advocate as an

erroneous identification of anti-imperialism with a policy of indiscriminate opposition to all the great powers. This view leads to simplified reactions, ignoring that current imperialism forms a system of aggression under the command of Washington. Only the recording of this fact allows us to conceive an anti-imperialist strategy adapted to the 21st century.

It is therefore only logical that Katz prioritises the struggle against one imperialist camp while coquetting with a tactical alliance with the other imperialist camp.

Consequently, Katz advocates a “triple strategy for Latin America” that he summarises in the formula: “Resistance to the United States, renegotiation with China and the emergence of regional unity.” Naturally, we are fully aware that countries striving for independence and equality have to pursue a realpolitik since we do not believe in the Stalinists utopia of building socialism in one country. Hence, opening trade relations and asking for a loan might be a necessary step for such countries.

However, a victorious workers and peasant government in a country of the Global South can not limit itself to opening such diplomatic and economic relations with other countries (including Great Powers). It will have to focus on expanding the revolutionary process, since the only assurance for workers and peasant power is strengthening the struggles of its class brothers and sisters to overthrow the ruling class in their countries.

In addition, it is absolutely legitimate for a country striving for independence to enter into diplomatic and economic relations with other countries (including Great Powers). But why only “renegotiate with China”? Is it not a fact that such countries can equally be obliged to do business with US imperialism? Look at Venezuela, which sold its oil to Washington even in the heydays of Hugo Chavez’ Bolivarianism.

It seems Katz’s advocacy of a strategy for “national sovereignty” is a program for Latin American countries to join BRICS and side with Chinese and Russian imperialism against the US. This is also the meaning of his support for the Putinist concept of “multipolarity”. True, Katz wants to combine it with a “radical-revolutionary program”. But first, he wants to strengthen the China/Russia-led BRICS because “multipolarity” would “weaken imperialist domination while forging the pillars of a post-capitalist future.”

Effectively, this is a version of the reformist strategy of transformation in stages. In the domestic terrain, this usually means to get a majority through parliamentary elections and then gradually begin the transformation to socialism. In the field of foreign policy, for Katz it means to “support the creation of a multipolar world that paves the way for the transition to socialism.” In fact, a “multipolar world” only means a world dominated by several Great Powers enmeshed in inter-imperialist rivalry.28

Objectively, this is a program of one-eyed anti-imperialism and has nothing to do with authentic socialism. In domestic policy it results in defending bourgeois property relations (as has been the case for example in Venezuela during the past quarter of a century). In foreign policy, it results in support for Chinese and Russian imperialism.

But, as Lenin explained, the task of socialists is not to support one Great Power against another — irrespective of if it is bigger or smaller, stronger or weaker — but to fight against all imperialists:

From the standpoint of bourgeois justice and national freedom (or the right of nations to existence), Germany might be considered absolutely in the right as against Britain and France, for she has been “done out” of colonies, her enemies are oppressing an immeasurably far larger number of nations than she is, and the Slavs that are being oppressed by her ally, Austria, undoubtedly enjoy far more freedom than those of tsarist Russia, that veritable “prison of nations”. Germany, however, is fighting, not for the liberation of nations, but for their oppression. It is not the business of socialists to help the younger and stronger robber (Germany) to plunder the older and overgorged robbers. Socialists must take advantage of the struggle between the robbers to overthrow all of them.29

Conclusions

1. I reject Katz’s theory of a US-led “Empire” that dominates the world. New imperialist powers — most importantly China and Russia — have emerged that put an end to Washington’s absolute hegemony in the period after 1991. These new powers have accumulated substantial economic and military strength and pursue their own imperialist interests, independent of and in rivalry against the US.

2. Katz’s theory is mistaken as it subordinates the contradictions between classes, nations and states to only one contradiction: the US-led “Empire” against the rest of the world. In reality, Marxists have to defend the interests of the popular masses and semi-colonial countries of the South against all capitalist classes and against all Great Powers — those in the West (US, Western Europe, Japan) and those in the East (China, Russia).

3. To justify his one-eyed anti-imperialism, Katz turns Lenin’s theory of imperialism on its head and transforms it into an idealist conception of “imperialism” as aggressive foreign policy. But imperialism is the final epoch of capitalism in which a small group of monopolies and Great Powers try to expand their political and economic spheres of influence against the popular masses and in rivalry with each other.

4. Katz argues that imperialism as a system of rivalling Great Powers ended by 1945 and was replaced by a US-led “Empire” in which Washington dominates Western states. As a result, inter-imperialist contradictions have disappeared. This is a mistaken interpretation of historical developments since World War II. Inter-imperialist contradictions were subordinated to the overriding contradiction between the imperialist powers and the degenerated workers states (the bloc led by the Soviet Union). After the collapse of Stalinism in 1991, the US became the absolute hegemon. However, this brief period ended with the 2008 Great Recession, as new imperialist powers emerged in the East. Today, the main inter-imperialist contradictions are between the Western and Eastern bloc. However, this does not mean that these are homogenous alliances, and it is quite possible that frictions within both blocs could emerge in the coming period.

5. Katz’s view that Lenin’s program of defeatism only applies to revolutionary situations is wrong. The Bolshevik leader considered this program as appropriate for the struggle against all Great Powers in the whole epoch of imperialism, not only in specific situations.

6. Katz’s analogy of the US-led “Empire” with Tsarist Russia in the 19th century and his consequential advocacy of applying Marx’s tactic (with the US-led “Empire” as the main enemy in place of Tsarist Russia) is inappropriate. We do not live in a US-dominated unipolar world and it is the dictatorships of Putin and Xi that most resemble the Tsarist autocracy. But this analogy is also wrong because it is deeply unhistoric and applies an approach to states and wars that was justified in the epoch of transition from feudalism to capitalism to the epoch of decaying capitalism. In the epoch of rising capitalism, the bourgeoisie of various Great Powers in Europe played a certain progressive role and their struggle against Tsarist Russia — the main bastion of feudalism — had to be supported. In the epoch of decaying capitalism, the bourgeoisies of all imperialist powers have a thoroughly reactionary character.

7. Katz’s program of one-eyed anti-imperialism has reactionary consequences, as it objectively lends support to Great Powers that are opponents of the US (for example China and Russia). Likewise, he advocates support only for those workers and popular struggles directed against the US-led “Empire” and its allies. In contrast, he refuses to support, and even denounces, such struggles if they are directed against Russia and China and their allied regimes.

8. Socialists today must oppose not only one Great Power or one group of allied Great Powers but all imperialists – those in the West and in the East. No solidarity with any of these robbers — only international solidarity with the workers and the oppressed fighting for freedom and to live in dignity.

Michael Pröbsting is a socialist activist and writer. He is the editor of the website http://www.thecommunists.net/, where a version of this article first appeared.

- 1

The contributions of Claudio Katz are: Russia an imperialist power? Part I-IV, May-June 2022 (https://links.org.au/is-russia-an-imperialist-power-non-hegemonic-gestation, https://links.org.au/russia-imperialist-power-part-ii-lenins-legacy, https://links.org.au/is-russia-an-imperialist-power-continuities-reconstructions-ruptures and https://links.org.au/is-russia-an-imperialist-power-benevolent-glances); Desaciertos sobre el imperialismo contemporáneo, 18.09.2022, https://katz.lahaine.org/desaciertos-sobre-el-imperialismo-contemporaneo/. My replies are: Russia: An Imperialist Power or a “Non-Hegemonic Empire in Gestation”? A reply to the Argentinean economist Claudio Katz, New Politics, 11 August 2022. https://newpol.org/russia-an-imperialist-power-or-a-non-hegemonic-empire-in-gestation-a-reply-to-the-argentinean-economist-claudio-katz-an-essay-with-8-tables/; “Empire-ism” vs a Marxist analysis of imperialism. Continuing the debate with Argentinian economist Claudio Katz on Great Power rivalry, Russian imperialism and the Ukraine War, LINKS, 3 March 2023, https://links.org.au/empire-ism-vs-marxist-analysis-imperialism-continuing-debate-argentinian-economist-claudio-katz.

- 2

Claudio Katz: Coincidencias y discrepancias con Lenin, 15.10.2024, https://katz.lahaine.org/coincidencias-y-discrepancias-con-lenin/. To our knowledge, this essay currently exists only in Spanish language. It has been reproduced on various websites. All quotes are from this essay if not indicated otherwise. The translation from Spanish to English are ours.

- 3

See: Chinese Imperialism and the World Economy, an essay published in the second edition of The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism (edited by Immanuel Ness and Zak Cope), Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2020, https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007%2F978-3-319-91206-6_179-1; China: On the Relationship between the “Communist” Party and the Capitalists. Notes on the specific class character of China’s ruling bureaucracy and its transformation in the past decades, 8 September 2024, https://links.org.au/specific-class-character-chinas-ruling-bureaucracy-and-its-transformation-past-decades; China: On Stalinism, Capitalist Restoration and the Marxist State Theory. Notes on the transformation of social property relations under one and the same party regime, 15 September 2024, https://links.org.au/transformation-social-property-relations-under-chinas-party-state-regime; China: An Imperialist Power … Or Not Yet? A Theoretical Question with Very Practical Consequences! Continuing the Debate with Esteban Mercatante and the PTS/FT on China’s class character and consequences for the revolutionary strategy, 22 January 2022, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/china-imperialist-power-or-not-yet/; China‘s transformation into an imperialist power. A study of the economic, political and military aspects of China as a Great Power (2012), in: Revolutionary Communism No. 4, https://www.thecommunists.net/publications/revcom-1-10/#anker_4; How is it possible that some Marxists still Doubt that China has Become Capitalist? An analysis of the capitalist character of China’s State-Owned Enterprises and its political consequences, 18 September 2020, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/pts-ft-and-chinese-imperialism-2/; Unable to See the Wood for the Trees. Eclectic empiricism and the failure of the PTS/FT to recognize the imperialist character of China, 13 August 2020, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/pts-ft-and-chinese-imperialism/; China’s Emergence as an Imperialist Power, in: New Politics, Summer 2014 (Vol:XV-1, Whole #: 57).

- 4

See: The Peculiar Features of Russian Imperialism. A Study of Russia’s Monopolies, Capital Export and Super-Exploitation in the Light of Marxist Theory, 10 August 2021, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/the-peculiar-features-of-russian-imperialism/; Lenin’s Theory of Imperialism and the Rise of Russia as a Great Power. On the Understanding and Misunderstanding of Today’s Inter-Imperialist Rivalry in the Light of Lenin’s Theory of Imperialism. Another Reply to Our Critics Who Deny Russia’s Imperialist Character, August 2014, http://www.thecommunists.net/theory/imperialism-theory-and-russia/; Russia as a Great Imperialist Power. The formation of Russian Monopoly Capital and its Empire, 18 March 2014, http://www.thecommunists.net/theory/imperialist-russia/.

- 5

V. I. Lenin: The Economic Content of Narodism and the Criticism of it in Mr. Struve’s Book. (The Reflection of Marxism in Bourgeois Literature.) P. Struve. Critical Remarks on the Subject of Russia’s Economic Development, St. Petersburg, 1894, in: LCW Vol. 1, p. 499

- 6

See: Anti-Imperialism in the Age of Great Power Rivalry. The Factors behind the Accelerating Rivalry between the U.S., China, Russia, EU and Japan. A Critique of the Left’s Analysis and an Outline of the Marxist Perspective, RCIT Books, Vienna 2019, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/anti-imperialism-in-the-age-of-great-power-rivalry/; The Great Robbery of the South. Continuity and Changes in the Super-Exploitation of the Semi-Colonial World by Monopoly Capital Consequences for the Marxist Theory of Imperialism, RCIT Books, 2013, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/great-robbery-of-the-south/

- 7

See e.g. V. I. Lenin: Eighth Congress of the R.C.P.(b.), March 18-23, 1919, Report on the Party Programme (1919); in: LCW 29, pp. 165-170

- 8

V.I. Lenin: Conspectus of Hegel’s ‘Science of Logic’ (1914); in: LCW 38, p. 171

- 9

V. I. Lenin: The State and Revolution. The Marxist Theory of the State and the Tasks of the Proletariat in the Revolution (1917); in: LCW Vol. 25, p. 447. We note that the official translation of this quote in the Collected Works starts with “Here was have what is most essential…” This is obviously a translation error which we have corrected.

- 10

V. I. Lenin: Imperialism. The Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916); in: LCW Vol. 22, p. 269

- 11

V. I. Lenin: Imperialism and the Split in Socialism; in: LCW Vol. 23, p.105.

- 12

V. I. Lenin: Imperialism and the Split in Socialism; in: LCW Vol. 23, p.107

- 13

V. I. Lenin: A Caricature of Marxism and Imperialist Economism; in: LCW Vol. 23, p.43

- 14

See Pröbsting: BRICS+: An Imperialist-Led Alliance. The expansion of BRICS reflects the rise of Chinese and Russian imperialism at the cost of their Western rivals, https://links.org.au/brics-imperialist-led-alliance

- 15

The figures are taken from James Eagle: Animated Chart: G7 vs. BRICS by GDP (PPP), 27 July 2023, https://www.visualcapitalist.com/cp/animated-chart-g7-vs-brics-by-gdp-ppp/

- 16

The figures are taken from James Eagle: Animated Chart: G7 vs. BRICS by GDP (PPP), 27 July 2023, https://www.visualcapitalist.com/cp/animated-chart-g7-vs-brics-by-gdp-ppp/

- 17

See: Henry Meyer, S'thembile Cele, and Simone Iglesias: Putin Hosts BRICS Leaders, Showing He Is Far From Isolated, Bloomberg, 22 October 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-10-22/putin-hosts-brics-leaders-in-russia-defying-attempts-from-west-to-isolate-him; Dr Kalim Siddiqui: The BRICS Expansion and the End of Western Economic and Geopolitical Dominance, 30 October 2024, https://worldfinancialreview.com/the-brics-expansion-and-the-end-of-western-economic-and-geopolitical-dominance/; Walid Abuhelal: Can the Brics end US hegemony in the Middle East? Middle East Eye, 22 October 2024 https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/can-brics-end-us-hegemony-middle-east; Anthoni van Nieuwkerk: BRICS+ wants new world order sans shared values or identity, 30 October 2024 https://asiatimes.com/2024/10/brics-wants-new-world-order-sans-shared-values-or-identity/

- 18

Ben Aris: Can the BRICS beat the G7? Intellinews, 19 October 2024, https://www.intellinews.com/can-the-brics-beat-the-g7-348632/?source=south-africa

- 19

Angus Maddison: Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030AD, Essays in Macro-Economic History, Oxford University Press Inc., New York 2007, p. 379

- 20

Paul Kennedy: The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000, Unwin Hyman, London 1988, p. 202.

- 21

Keishi Ono: Total War from the Economic Perspective, in: National Institute for Defense Studies (Ed.): The Pacific War as Total War: NIDS International Forum on War History: Proceedings (March 2012), p. 160

- 22

See LINKS: Imperialism, Great Power rivalry and revolutionary strategy in the twenty-first century, 1 September, 2023, https://links.org.au/imperialism-great-power-rivalry-and-revolutionary-strategy-twenty-first-century

- 23

V. I. Lenin: Under A False Flag; in: LCW Vol. 21, pp.143-144

- 24

V. I. Lenin: Under A False Flag; in: LCW Vol. 21, pp.143-144

- 25

V. I. Lenin: Under A False Flag; in: LCW Vol. 21, p.148

- 26

Gregory Zinoviev: Der Krieg und die Krise des Sozialismus, Verlag für Literatur und Politik, Wien 1924, p. 115 (our translation)

- 27

V. I. Lenin: The Conference of the R.S.D.L.P. Groups Abroad (1915); in LCW 21, p. 159

- 28

For a critique of the concept of see: “Multi-Polar World Order” = Multi-Imperialism. A Marxist Critique of a concept advocated by Putin, Xi, Stalinism and the “Progressive International” (Lula, Sanders, Varoufakis), 24 February 2023, https://www.thecommunists.net/worldwide/global/multi-polar-world-order-is-multi-imperialism/; see also my speech at the Socialism 2023 Conference in Malaysia, https://www.thecommunists.net/rcit/michael-probsting-speaks-at-socialism-2023-conference-malaysia-about-de-dollarization-and-multipolarity/

- 29

V.I. Lenin: Socialism and War (1915); in: LCW 21, p. 303