Aotearoa/New Zealand: A history of the Unite Union

By Mike Treen, Unite national director

[All four parts of this series can be downloaded as a single PDF file here.]

June 27, 2014 – Unite News, submitted to Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal by the author – The following history was prepared as part of the contribution by Unite Union to the international fast food workers' meeting in New York in early May. Union officials and workers were fascinated by the story we were able to tell which in many ways was a prequel to the international campaign today.

* * *

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, workers in New Zealand suffered a massive setback in their levels of union and social organisation and their living standards. A neo-liberal, Labour Government elected in 1984 began the assault and it was continued and deepened by a National Party government elected in 1990.

The “free trade”policies adopted by both Labour and the National Party led to massive factory closures. The entire car industry was eliminated and textile industries were closed. Other industries with traditionally strong union organisation such as the meat industry were restructured and thousands lost their jobs. Official unemployment reached 11.2% in the early 1990s. It was higher in real terms. Official unemployment for Maoris (who make up 14% of the population) was 30%, again higher in real terms. Working class communities were devastated.

The National Party government presided over a deep and long recession from 1990-1995 that was in part induced by its savage cuts to welfare spending and benefits. They also introduced a vicious anti-union law. When the Employment Contracts Act was made law on May Day 1990, every single worker covered by a collective agreement was put onto an individual employment agreement identical to the terms of their previous collective. In order for the union to continue to negotiate on your behalf, you had to sign an individual authorisation. It was very difficult for some unions to manage that. Many were eliminated overnight. Voluntary unionism was introduced and closed shops were outlawed. All of the legal wage protections which stipulated breaks, overtime rates, Sunday rates and so on, went. Minimum legal conditions were now very limited – three weeks holiday and five days sick leave was about the lot. Everything else had to be negotiated again. It was a stunning assault on working people. Union bargaining, where it continued, was mostly concessionary bargaining for the next decade.

The central leadership of the Council of Trade Unions (CTU) capitulated completely to these changes and refused to organise broader industrial struggle, let alone a general strike, despite the fact that there was overwhelming sentiment for such a struggle. The impact of the recession and the new law was intensified by the demoralising effect of this failure to resist. Union membership collapsed within a few years from over 50% of workers to around 20%. In the private sector, only 9% of workers today are represented by a union. Whole sectors of industry and services were effectively deunionised. Real wages declined in the order of 25% for most workers by the mid 1990s and have recovered only marginally since. Union membership rates have also failed to recover despite a broad economic recovery from the late-1990s on that resulted in unemployment dropping to under 4% by 2007.

In 1999, a Labour-Alliance government [the Alliance Party was a leftish split

from Labour] changed the law on union rights. While voluntary unionism

was left untouched, union organisers regained access to workplaces for

the purpose of recruitment. The unions now had the right to pursue

multi-employer collective agreements through industrial action.

Political and solidarity strikes are still outlawed, and you can only

legally take action in the bargaining period. But there are few other

limitations. You didn’t have to give notice of strike action to

employers unless they were an essential industry or even conduct secret

ballots for example (requirements since reintroduced by the current

National government). Replacing striking workers with outside scabs was

also outlawed.

Campaign to organise the unorganised

A small group of unionists and left-wing activists began a campaign to organise the unorganised in mid-2003. We sought to challenge the notion that it was impossible to reunionise those sectors and that young workers simply weren’t interested in unions.

The initial group came out of the breakup of the Alliance Party in the wake of the decision by the Labour Party/Alliance Party government elected in 1999 to support the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. The Alliance Party was eliminated from parliament in the July 2002 election. The group that started the union organising drive was led by Matt McCarten, Kathryn Tucker, Alex Muir and myself – all Alliance Party activists or officials. McCarten had a national political profile as the former president of the Alliance Party. I had considerable social movement organising experience and Muir had the skills needed to create our membership systems and database. Tucker volunteered for a “few weeks” to help set up but proved to be an exceptionally talented recruiter and organiser and ended up staying for 6 years.

Hotel picket, 2003.

Initially, McCarten hoped to simultaneously build the new union and maintain Alliance as a political party. But the Alliance brand was damaged beyond repair and he quit any role in the organisation in November 2004. He subsequently assisted in the formation of the Maori Party in 2004 and the Mana Party in 2011. McCarten wrote a weekly column in one of the main, New Zealand Sunday newspapers beginning in late 2004. His public profile gave media opportunities to Unite that were very rare and opportune for a union organising drive.

In February 2014, McCarten announced that he had accepted a posting as chief of staff of the new (September 2013) leader of the Labour Party, David Cunliffe. The announcement came from left field – literally and figuratively.

The founding member group of the union organising drive was convinced that the legal opportunities for accessing workplaces in the Labour/Alliance government’s employment law adopted in 2000 weren’t being exploited aggressively enough, in particular the new access rights. Another element of the new law that helped was that employers had to deduct union fees unless it was specifically prohibited in the individual agreement. We also had a gut feeling that after six-seven years of economic expansion and relatively low unemployment in New Zealand, the element of fear and intimidation preventing workers from signing up for a union would have subsided. The worry of losing a poor minimum wage job and finding difficulty to get another was no longer so prevalent among the workers to whom we were appealing. Most importantly, we had confidence that workers, and young workers in particular, would respond to new approaches that gave them a chance to fight for themselves.

The vehicle for the organising drive was Unite Union, which at the time was a very small union of about 100 members. It was originally launched in October 1998 to oppose a work-for-the-dole plan by the National Party government of the day. That government plan didn’t proceed. Unite became a general membership union that workers could join who didn’t fit the membership rules of the existing unions. It had two small collective agreements for English language school teachers. It was run by union officials from other unions in a voluntary capacity. It’s membership rule allowed it to represent virtually anyone and it had the additional benefit of being an affiliate of the central union body, the Council of Trade Unions.

There was some suspicion about the Unite project – especially from unions close to the Labour Party. Unions already present in industries where we gained recruiting successes also had obvious concerns. One leading union official even described us as a “scab union” and a motion was moved at the Council of Trade Unions National Executive to expel Unite. Then-CTU President Ross Wilson was supportive of our work and intervened to prevent the motion being put. Other officials, including from Labour Party affiliated unions, were excited by what we were trying to do.

Unite initially planned to organise as a “community union”, but it soon became obvious we had to go after the big chains in fast food, cinemas, and hotels. They had all been largely deunionised in the early 1990s. We immediately had a burst of publicity during July and August 2003 when the government said it was going to decriminalise prostitution. We said we would accept prostitutes as members. Coincidentally, a strip club and brothel owner sacked six staff who asked for Unite’s help. We shut down his three premises with a picket and a video camera to take footage of any customers going in – needless to say, none did.

Unite had a way of getting noticed.

Publicity led to us being noticed and called up by workers wanting union representation. Two call-centre workers volunteered to help conduct a recruitment drive at their workplaces. One was a security company monitoring centre and the other was the Restaurant Brands call centre for Pizza Hut with 100 staff. Other unions those workers had asked for help told them they had to sign up a majority of staff before they could expect help. We signed up a big majority of staff at both. We signed a collective at the Restaurant Brands call centre in June 2004 – the first for the fast food industry in years. At the security company, a collective was signed in July 2004. The majority of staff at the call centre of Baycorp, the largest debt collection agency in the country, also signed up with Unite after a worker came to us over an unjustified dismissal. We signed a collective agreement there in September 2004.

We tried new ways of signing up. We used a membership form that was more like a petition form. We kept entry union dues low or even free. Ultimately, we settled on a standard of a minimum dues of $2 a week until a first collective agreement was signed when a fee of 1% of wages up to a maximum (initially $4.50) was charged. Again a percentage fee was an obvious thing to do for workers whose income varied radically from week to week but which isn’t done by any other union that I am aware of. We found this dues structure was no barrier to recruitment. What we also discovered was that we could recruit someone in a five minute conversation if we got to speak to them individually.

We also started recruiting in hotels with some success. We had an early, highly publicised dispute in November 2003, organising several loud, early morning pickets outside the Quay West hotel in Auckland to get a collective agreement for contract cleaning staff. Matt McCarten was arrested (soon released), our sound gear was confiscated by police and we were taken to court for an injunction to stop any further picket action. By the end of 2004, we had collective agreements at a dozen hotels.

2004 recruitment campaign in cinemas

As a test of the mood among the young, casualised workforce in New Zealand, we decided in 2004 to go after the three main cinema chains – Readings, Berkeley (now merged with Hoyts) and Village SkyCity (now Event Cinemas). Unite volunteer Kathryn Tucker led this work and we had immediate success. We recruited hundreds of members and had over 80% of the staff in the union. We secured collective agreements by the end of 2004 at Berkeley’s and Village SkyCity without the need to take any action. We began to negotiate a new standard whereby all paid breaks are 15 minutes rather than 10; we have won this in all subsequent Unite collective agreements.

We also discovered that some of the strongest motivators for workers may not be just bread and butter issues. Of equal, or greater, importance are issues involving personal dignity. Cinema workers got two free tickets each week but these could be taken off you for any petty infraction. If you were five minutes late, if you had a sick day, looked the wrong way at your manager, you could lose your “comps”. We won the movie tickets as a right that could not be arbitrarily taken away.

Readings Cinema was reluctant to sign, however. In the knowledge that a large proportion of the profit at a cinema comes from the sales of confectionery, we had a large picket outside Readings in Wellington in September 2004 with free popcorn. It costs virtually nothing to make, and an old lefty friend had a machine for making it. We quickly won a substantial pay rise and an agreement to eliminate youth rates over two years. Again, we made national news.

Readings Cinema picket 2004.

Through these recruitment drives, we were confident that we could take on the fast food companies. We made the mistake, however, of thinking we could fight them one by one. We went after Burger King first. We thought it would be an easier target as it was smaller than Restaurant Brands (KFC, Pizza Hut and Starbucks) and it had no franchisee stores like McDonald’s. That was a mistake. We signed up several hundred BK members in early 2005, but negotiations became protracted. BK used a very high proportion of workers on temporary visas and we were relying too much on untrained, union volunteers with little or no experience.

The company was owned by three individuals with a high degree of hostility, obliging them to dip into their pockets to fight us. To knock BK over would require a high-profile public campaign. The sort of resources required to do that meant we may as well take on all the fast food chains at once. Negotiation of the BK agreement was put on hold until we had forced the other fast food companies to negotiate meaningfully. In the end, BK was the last company to sign a collective agreement. But the seeds were sown for what followed.

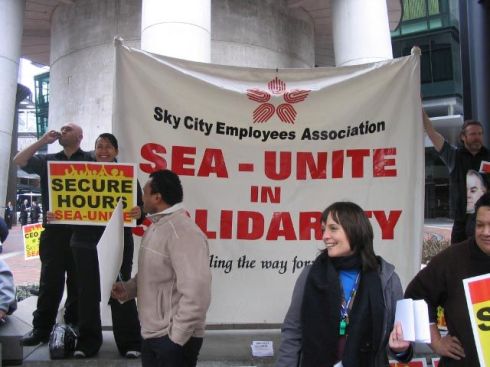

During 2005, a number of workers from the SkyCity casino in Auckland joined Unite. Accepting this group as members was the most difficult and controversial decision of Unite because another union had a collective agreement with the company. Luckily, our newly established presence helped lead to union membership as a whole expanding, to a combined total of about 1000 members. Unite became the majority union on site and we now negotiate a joint collective agreement with the other union. Casino Unite members have a semi-autonomous association called SkyCity Employees Association-Unite (SEA-Unite).

SkyCity members of SEA-Unite picket company.

2005 fast food recruitment drive

Beginning in May 2005, we launched a recruitment drive at all the main fast food restaurants in preparation for the launch of the public campaign. This included Restaurant Brands (KFC, Pizza Hut and Starbucks), McDonald’s (including all franchisees), BK, Wendy’s and Red Rooster (since closed). We negotiated “access protocols” with each company. We had a legal right to access to talk to staff. The companies were determined to keep us from going back of house to talk to staff during work hours, so we accepted the “compromise” that a manager would send each staff member out for a one-on-one chat for a few minutes. We already knew that this “compromise” would enable us to recruit in the hundreds.

We had the assistance of a very smart young volunteer, Simon Oosterman, who brought in a youthful tech-savvy that combined well with Matt McCarten’s political party campaign experience and my own social movement organising. Two other central organisers of the campaign still with Unite today were Joseph Carolan and Tom Buckley. At the beginning of 2006, John Minto – an iconic figure of the anti-apartheid movement in New Zealand – gave up his teaching job and joined the Unite project. As well as his organising and negotiating skills, Minto was a household name and also had a weekly column in the Christchurch daily paper. Minto left Unite in 2012 to concentrate on building the Mana Movement.

SuperSizeMyPay.Com.

Oosterman designed the website and publicity materials that became SuperSizeMypay.com. In doing so, we maxed out our personal credit cards and homes were refinanced. A bus was bought with a kick-arse sound system able to be attached to the roof.

We had identified the 3 key issues for which we would negotiate in each and every collective agreement and which we considered essential:

- $12 an hour minimum wage (at the time the legal minimum was $9.50 for adults and $7.60 for youth aged 16-19)

- No youth rates

- Secure hours – which in practise meant prohibitions on hiring new staff until existing staff had been offered hours that were available.

Within a few months, one thousand fast food workers had joined Unite. The companies didn’t know what hit them when the campaign was publicly launched on November 23, 2005 with “the world’s first Starbucks strike”. We decided to do Starbucks because it would be the company where Restaurant Brands would think we had the least chance to convince workers to go on strike. Partly because of store locations, the staff tended to be bit more middle class and trendy. On the morning of the strike, the company’s chief exec Vicki Salmon went on the main morning radio news programme to be interviewed alongside Matt McCarten. She made fun of the fact that only a “handful” of Starbucks’ “partners” were in the union. So we got hold of a bus and shut down 10 stores in Auckland, bringing all the workers to the Karangahape Road store where we had originally determined the world’s first Starbucks strike would take place. Fair trade coffee was served for free outside that store during the strike.

Television news reporters followed us for the day. Simon Oosterman was concerned with “the picture” because the first store was in a mall and TV cameras weren’t allowed inside. But completely unscripted, the union delegate there led his team out a side door of the mall, threw his apron on the ground and announced to the waiting TV crew “I’m on strike”. That image become one of the iconic ones of the campaign. We went after the fast foods’ brand image as well. KFC’s company logo, “Kiwis for Chicken”, became in our campaign language, “Kiwis for Cheap”!

Campaign highlights

This was followed up with dozens of strikes and protests at the fast food companies. The following are highlights. Usually, strikes lasted for an hour or two and only at the busiest times of the day. We didn’t try to “force” all the members to strike as we needed time to build their confidence that they could strike and still keep their job. Overwhelmingly, picket lines were respected by customers, whether walking or driving in.

- Dozens of KFC and some Pizza Huts strikes, starting in December 2005 with a strike at the newly renovated flagship Balmoral store led by a strike committee of workers on youth rates.

- No-warning, “lightning strikes” beginning on December 21 at Lincoln Rd KFC. The busy, long, industrial West Auckland Rd was also the scene for the first car caravan strikes, going from store to store and creating the first BK strike in the process.

- Actions at KFC’s outlets in Wellington and Whangarei. Ten managers turned up to the Porirua store from a regional managers meeting, but the store was shut down with every worker on duty striking.

- The Restaurant Brand’s call centre had 20-30 short strikes led by a delegates committee. Often these would begin with a short , 15-minute strike of all workers and then those who wanted to work could return while those who wanted to strike longer could do so. The backlog of calls would never be cleared in the evening. There were well over two dozen “lazy strikes” where smaller groups of workers would decide they needed a holiday or would turn up late as a form of strike action.

- A McDonald’s strike and rally in February 2006 outside one store in central Auckland, when the company threatened to sue workers if they attended the union meeting planned for February 12. All union members on shift met and voted to strike and join the picket outside despite the threat.

- A February 12, mass, town hall public meeting and stop-work for Unite members in support of the campaign. A range of speakers from unions and political parties spoke. Musicians and comedians performed, including NZ’s first “NZ Idol” Rosita Vai, herself a former KFC worker. Worker after worker explained to the meeting what they were fighting for.

- A February 22, anti-youth rates day of action with rolling strikes at KFC’s Manukau, Massey, Lincoln Rd and Balmoral outlets. Picketers were picked up and taken around in a supporters’ bus.

- A “McStrike” day on March 3 affecting six stores with hundreds rallying in Queen St, central city, Auckland. A supporting strike was held at the Restaurant Brands call centre and workers marched down to join the McD’s picket.

- March 18 was dubbed the “Big Pay Out” with strikes and a march of 1000 young people up Queen St , followed by a free concert in a park. McD’s rostered union members off that day so they couldn’t join the strike, so we recruited new members in the morning who could join the strike action. Four workers who had been in the union less than an hour led the first strike at downtown McD’s to march up Queen St, stopping at each store on the way.

In early 2006, a private members bill to abolish youth rates sponsored by Green MP Sue Bradford was pulled from the hat and allowed to be discussed and debated in Parliament. It helped strengthen our campaign.

A March 20, 2006 high school student strike and march through central Auckland of 1000 students against youth rates. The strike was organised by “Radical Youth” a group based in the high schools and inspired by Unite’s campaign and Bradford’s private members bill. We supplied 20 buses for the different schools to get there.

Fast food collective agreements signed 2006.

Restaurant Brands sued for peace five days after the high school student strike. We signed an agreement substantially lifting wages and abolishing youth rates over two years. There were strong clauses requiring available work hours to be first offered to existing staff. Breaks were protected. Three-hour minimum shifts were guaranteed. The settlement made front-page news in the country’s biggest daily newspaper The New Zealand Herald. We were strongest at Restaurant Brands because it has no franchise stores; is a publicly listed company, and the KFC stores tend to be in solid working class communities. Restaurant Brands also agreed to pay a union member-only allowance of 1% of workers wages each quarter in recognition that the negotiated contract would be passed on to all staff.

McDonald’s resisted the signing of collective agreements longer and harder than Restaurant Brands. They de-recognised half our initial 800 recruits on a technicality. Rather than go to court over the issue, we simply went out and recruited them all over again. They demanded $5000 to upgrade their software to do fee deductions and demanded we agree to their taking a 2.5% fee on union dues for the trouble they had to go to.

The day of strike action and public protest held on March 3, 2006, was in response to McDonalds’ intention to pay national minimum wage increases to non-union staff as of March 6, three weeks earlier than they were legally required to do so. “McStrike” was the theme of that day as McDonald’s workers from across Auckland joined the Queen Street picket including workers from stores at Royal Oak, Manukau, Glenfield and Wairau Rd. They were joined by 35 fast food call centre workers and Starbucks workers, to say they were proud to be in their union. A letter confirming the company’s position stated: “As advised at the last meeting, it is likely McDonald’s will decide not to pay the above [minimum wage] increases to Unite members. That is simply because franchisees and McDonald’s are concerned that Unite’s industrial tactics have the objective and/or effect of damaging the McDonald’s brand and their business and they don’t see any merit in rewarding that behaviour with a pay increase”.

During the protest, McDonald’s crew trainer and Unite delegate Heni Moeke, representing the first 750 McDonald’s Unite union members, issued the transnational with a legal document charging the company with “unlawful failure to bargain” and “unlawful discrimination on grounds of union membership”. The majority of staff were being paid below the new minimum wage during the three weeks before the new rate became legal and the company hoped members would resign from the union to get the pay rise. They were to be disappointed because few members resigned. With the company under threat of court action from Unite, members received the early minimum wage rise as well.

Union members at McDonald’s had their hours cut or failed “performance pay” reviews. We had to go to court twice during 2006 to try and force the company to meet their legal obligation to negotiate “in good faith”. Their chief advocate, Tony Teesdale, had a reputation as hard man for the bosses and boasted that he had helped draft the 1990 anti-union law. He assaulted an Australian film maker in his office foyer, cutting her finger as he wrenched the camera from her and removed her film.

May Day 2006 became the second Unite and Radical Youth-organised youth protest against youth rates. The action took place in the early evening, after school, and was the largest May Day event in Auckland for decades.

Pickets and strikes continued at McDonald’s wherever possible. In the end, I think the company concluded that no matter what they threw at us we were never going to give up and go away. On December 5 2006, McDonald’s agreed to abolish youth rates and a collective agreement was settled. A modest, one-off, union member-only bonus payment was won as part of the settlement. Clauses on protecting hours of work, a three-hour minimum shift and guaranteeing 15-minute paid breaks were also agreed. The “Terms of Settlement” for the agreement was signed by Matt McCarten and the company in Matt’s hospital room.

Jared Phillips joined Unite in late 2006 and remains with us today. He led the organisiation of the much smaller Wendy’s chain which included strikes at some of their stores on February 25, 2007. A collective agreement was signed with Wendy’s in April 2007.

Extending Unite’s reach

Unite was always looking to ways to bring our members additional benefits. In late 2006, Unite contracted with Te Wananga o Aotearoa – a Maori-led tertiary institution – to offer computer classes for union members. We set up a Unite school in central Auckland and provided classes days and evenings, seven days a week, so our members could attend. A casino worker on a rotating 24-7 shift could enrol and complete a course. For a few years, one of the main buildings in Queen St was named “Unite House” with red flags flying from the roof – much to the consternation of friend and foe alike. Thousands of workers graduated from these courses.

In July 2006, SkyCity casino workers won pay rises of 5-9% after a campaign of two-hour, all-out strikes several times a week combined with rolling strikes by department. The company was taken by surprise at the determination of the SEA-Unite members.

SEA-Unite members join picket in 2006.

In late 2006 and 2007, Unite unionised a factory owned by Independent Liquor at the request of some workers. This was a very anti-union employer. Strikes and pickets were needed to get a collective agreement, the first in the company for 20 years. After a while, however, we realised that we were probably getting beyond core business and agreed to allow the Engineers Union which covered workers in other liquor manufacturing plants to take over representation.

Unite also extended its representation with a hotel campaign involving strikes (and occasional lockouts) at a number of hotels in early 2007. The ADT-Armourguard monitoring centre struck on Christmas Eve – the busiest night of the year to secure an improved offer for a renewed collective agreement.

We continue to expand our presence in English language schools from the original two with collective agreements to about a dozen. Strike action was required at three, however a number have since closed in what is a fickle business. Those schools with agreements radically improved their security of hours, tenure and pay in an industry where teaching staff were routinely treated as casual workers only.

On August 11, 2007, Unite organised a third rally against youth rates with Radical Youth. This time it was supported by the CTU, National Distribution Union and Youth Union Movement. The final reading of Sue Bradford’s amended bill passed through Parliament later that month, eliminating youth rates for 16 and 17 year olds after three months or 200 hours of employment. Unite had already eliminated the rates in the industries we organised in the previous few years and now most employers gave up on trying to use them.

June 2008 saw a number of strikes at the food court of Auckland Airport in support of collective agreement negotiations. We still have no agreement at the airport, although the company did significantly increase wages and improve conditions in an attempt to ward us off. We campaigned publicly that the company had medieval employment conditions after the company told us “the shift ends when the supervisor dismisses the worker”. A public campaign of short strikes has resulted in a tenure-based pay scale, improved breaks and stabilised hours of work. June 2008 also saw new “Popcorn Strikes” at the SkyCity cinema chain in Auckland. Rather than giving away free popcorn, patrons were called upon to boycott the candy bar to show support. At a St Lukes cinema strike, two temp workers hired for the day joined the union and joined the strike, along with one worker transferred in from another cinema. The Hoyts cinema chain signed a collective that year as well.

HMSC workers protest outside Airport terminal.

August 2008 saw a ban on cleaning up bodily fluids left by guests in the MCK hotel chain to support collective agreement negotiations.

August through October 2008 saw three months of rolling strikes at the casino in Auckland by members of both SEA-Unite and the Service and Food Workers Union (SFWU) to secure a renewed collective agreement. With 1000 members, the two unions there still have only one third of the total staff employed. In these circumstances, it is difficult to shut the casino down through strike action. Guerrilla actions were seen as a better option to keep the company guessing. Casino staff would decide in small groups, department by department, when and where to take strike action, according to how busy things were. If the company got wind of an action and called in extra non-union staff, the action would be postponed. HR managers had to be billeted in the hotel 24-7 to manage the situation for the company.

We walked the casino floor with megaphones and whistles when calling for an all-out strike. It was good reintroduction for Grainne Trout (former Managing Director of McD’s when we negotiated the first contract), who was appointed HR manager at the casino in May 2008 just a few months before the strikes began. When she was interviewed on national television in 2010 about Unite, she was asked if she considered unions “a necessary evil”. She responded that she wouldn’t use the word “necessary”.

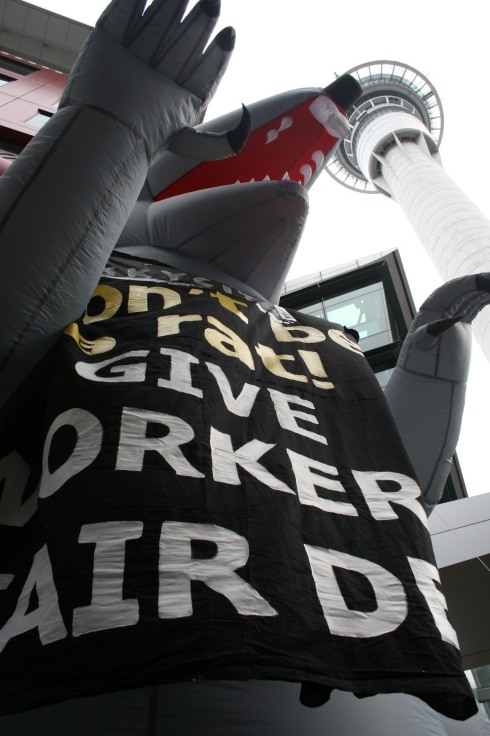

'The Rat' makes its appearance in 2008.

The 2008 casino strike saw the first appearance of “The Rat” – a six metre, inflatable prop first seen by McCarten in use by unions in New York City on the TV series The Sopranos. The rat had a huge banner around its neck saying “SkyCity don’t be a rat – give workers a fair deal”. It has proved to be a useful addition to the Unite armoury and has been deployed with effect by other unions when needed. In late 2008, Unite launched a campaign to unionise the research company call centres operating in NZ. This was in response to an appeal from the Australian call centre union, the National Union of Workers. We succeeded in unionising most of them and getting collective agreements after some tough battles and a number of strikes and lockouts. When we were locked out, we barricaded the doors so the company couldn’t get in either. One set of negotiations went all night until it was settled. Today, most of the centres that became unionised have relocated to other countries or switched to computer-based home calling. But workers at other centres have joined Unite. The Vodafone call centre, for example, came on board, along with some direct-sales call centres.

In 2010, we tried to take on the Australian retailer JB Hi FI – unsuccessfully as it turned out.

In August 2010, Burger Fuel used the 90-day trial period law to sack a worker on her 89th day. A quick campaign saw the company pay compensation and agree never to use the law again. We also mounted a campaign against employers in Christchurch who bullied their employees following the 2010 earthquake in that city.

In March 2011, First Security patrol staff were locked out after a two-hour strike. Unite responded by putting a blockade on the company premises to stop any vehicle leaving. An on-the-spot deal was brokered whereby the lockout was lifted with negotiations at 9am the next day – a Sunday. The result was a much-improved offer which was accepted by the members. Shortly afterwards, the First Security prison escort staff took lightning strike action threatening to cripple the courts. On-the-spot significant improvements in pay and conditions of employment were secured.

First Security picket.

2011 saw another protracted dispute at the SkyCity casino. A strike began at midnight on New Years Day. Again, we walked the casino floor with whistles and megaphones, but in a sign of a more aggressive attitude, I was assaulted by a security guard inside the casino. This year when we tried partial strikes, staff were immediately suspended until the following day or longer. A larger lockout planned by the company was met with a union blockade of the casino entrances and all-day negotiations that resulted in an improved offer from the company which was accepted.

Substantial settlements separate from collective agreement negotiations have been won for small groups of casino staff over the years. The largest was $150,000 paid to conventions staff after a several-year dispute. Again, media has been used where necessary. The company lost tens of thousands of dollars in bookings when we issued a worldwide press release explaining that the place was infested with fleas. A worker who was to be sacked for carrying a Bible was reinstated after the company was humiliated in the media.

We set up a “Rat Patrol” in February 2009 to take action against any employer using the 90-day right-to-sack law. This has been used on several occasions with success.

Renegotiating the fast food contracts 2008 – 2013 – riding the minimum wage hikes

We have succeeded in maintaining our membership and renegotiating collective agreements from 2006 through to today. This has not been without attempts to push back however – especially at McDonald’s and Burger King.

A major element on our side was the fact that the minimum wage was being increased strongly following the formation of the Labour-led government in 1999. The previous National Government of 1990-1999 increased the minimum wage only once. In real terms, it had declined from 50% of the average wage to 30%. The 1999-2008 Labour government restored its value to 50% of the average wage. The adult minimum rate went from $7 an hour in 1999 when Labour was elected to $12 when they left. The youth rate went from $4.20 an hour for youth up to 19 years of age to a “new entrant” rate of $9.60, which applied to 16 & 17 year-olds for three months. Unite was able to ride those increases across the period we have been bargaining with the fast food companies, whose start rates were governed by the minimum wage. Because of that fact, we have been able to count on above-inflation rate increases most years for the start rate in agreements. We could then focus on the gains in service, secure hours and breaks. Somewhat to our surprise, the current National Government elected in November 2008 appears to have maintained the minimum wage rate at 50% of the average wage – in fact it is slightly above with the latest 50 cent increase on April 1 this year.

But none of this happened without significant pressure from without. The SupersizeMyPay.Com campaign from 2003 to 2006 kept the pressure on publicly to lift the minimum wage to $12 and abolish youth rates. Both objectives had been achieved by 2008. Following the election of the National Party that year, Unite launched an audacious campaign in June 2009 for a citizens-initiated referendum for a $15 an hour minimum wage. The referendum drive lasted for one year. 200,000 signatures were collected. Throughout the one year, there was a visible, vibrant, public presence of the referendum campaign at every event of significance to working class politics, culture, music, and sport. Support groups among students for the referendum were formed. A new layer of Unite volunteers came around who were inspired by the campaign and gave many hours of time to the petitioning effort.

The campaign failed to get the necessary 300,000 signatures to trigger a referendum, but it did change the landscape of political debate around the issue in NZ. The New Zealand Herald commissioned a poll in January 2010 which found 61% support and carried that news on its front page. $15 an hour became a slogan of the Labour Party in the 2011 election.

Unite ended up in disputes with local bodies and university councils that sought to infringe the right to petition in public places. We would be told again and again that the event was “private” and that you had to pay for stalls, even when the council was running the event. We refused to pay and simply set up where we wanted and defied them to arrest us (or at least arrest Matt on our behalf). It was one more example of the continual privatisation of public space. We fought the same fight at the Manukau Institute of Technology – one of the main tertiary institutions in Auckland.

A “Living Wage” campaign was launched in May 2012 by the Service and Food workers union, calling on employers to pay a minimum of $18.40 an hour. It has broad public support which has kept the pressure on the National government to maintain the value of the minimum wage.

However, The National Party government brought in laws in 2010 to strengthen the bosses’ bargaining power and weaken the unions. Access rights were restricted, sackings without cause are allowed for the first 90 days of a worker’s employment, youth rates were reintroduced in 2013 and the law governing rest breaks is to be repealed this year. These changes have had little effect on Unite because we have been able to prevent employers introducing many of them into our collective agreements. Unite made it clear to companies before bargaining last year that we would not sign any collective agreement with youth rates or a 90-day right to fire clause in them.

Unite acts in solidarity

Since its founding, Unite has joined in solidarity with any other union taking action. Our banners, placards, rat and bus have always been popular additions to picket lines. Unite has also been very active in action around migrant workers’ rights, in defence of civil liberties, protests against racist and misogynist media commentators and employer spokespeople, housing action groups, Occupy (for a period), unfair sackings, anti-TPPA protests, and protests against war and occupation – including in Iraq, Afghanistan and Palestine.

Unite truck and sound system supports “Aotearoa is not for sale” protest.

New technology and new tools

Unite is also one of the most successful unions for using some of the new ways of communicating. From day one, we collected emails and mobile numbers. Newsletters have been print and e-mailed. Facebook delegates networks have been established and proved effective tools during bargaining. A blog was established which quickly gained over 2500 subscribers. Survey Monkey has been used to test opinions and vote on contracts.

Brand by Brand 2008-14

At this point it is necessary to break from the largely chronological narrative to look at Unite’s relationship with each of the main fast food companies since the 2006 agreements were signed. Usually our collective agreements have been for two year terms although occasionally they were for a one-year term.

Restaurant Brands

We have successfully renegotiated the Restaurant Brands agreement every one or two years without a major dispute. We have continued to improve issues around security of hours, breaks, and overtime pay. Following the 2008 agreement, Unite doubled its membership at the company’s outlets from 1000 to 2000 in a few months. We have maintained these membership numbers despite a decline in Restaurant Brands’ total employment from 6-7,000 to 4,000. Last year, a media campaign was enough to put an end to attempts to remove staff with serious disabilities from KFC stores, and an in-store protest organised with a migrant workers group got a new job offer for a worker the company had dismissed when his visa had expired (he had renewed it four days after its expiry).

We prepared for the 2011 negotiations very carefully. During bargaining, we did a survey of hundreds of members on the important claims and the type of industrial action the members were willing to take. To avoid a fight, the company made a number of concessions including overtime pay after 8 hours and a doubling of the collective agreement allowance from $2 to $4 a week to be paid into a Unite Union controlled trust that we can use to purchase other benefits for union members.

These benefits include a membership card which can be used to access discounts at retailers, restaurants and hotels; life insurance; and a quarterly voucher valued at about $30 for use at cinemas or major retail chains. This is one benefit that cannot be “passed on” to non-union staff through improved terms and conditions of employment.

This union-member-only allowance has also been won at hotels and at cinemas. Together with Restaurant Brands, this covers half our membership of 7,000. We now have a majority of staff at KFC, Pizza Hut, Starbucks and the recently added Carl’s Jr Brand, in the union. Probably two out of three salaried managers and assistant managers at KFC are also in the union but not covered by a collective agreement. This is a vote of confidence by these crew who remain members after being promoted even though we don’t negotiate their agreement.

McDonald’s

McDonald’s fought back again in February 2008 when we tried to renegotiate the existing agreement for our 1300 members. We had to prepare and launch a major campaign in the stores again to get an agreement. On September 19, 2008, strikes began in the stronger stores. “The Rat” featured in this campaign. In one Hamilton store strike, only the managers brought in from Auckland 130 km away were left running the store. In September 2008, we won a $15,000 award against McDonald’s for a worker who quit after being harassed by a franchise owner for joining the union. By the end of October, we had organised 35 strikes at 24 different restaurants.

In November 5, 2008, we organised a strike in 20 stores in Auckland and Hamilton, and one in Wellington for the first time. A march was organised to the Hyatt Hotel in Auckland where the franchise store owners were having a national meeting. We announced that we were going to burn an effigy of Ronald McDonald outside the meeting to commemorate Guy Fawkes Day.

The company went nuts. The thought of a video going viral of Ronald being set on fire by a group of workers was a bit much for them. There were legal threats which we ignored. In the end, they invited myself and some delegates to speak to all the franchise owners on why they should settle with the union. In return, we agreed to not burn Ronald. We signed a terms of settlement for a new agreement on December 22, with the new collective running from March 1, 2009 until Feb 28, 2011. This agreement registered our biggest gains at McDonald’s. We succeeded in getting steps above the minimum wage for new employees after about three months, and then a year, and an extra $2.50 and $3.50 an hour above the minimum for shift supervisors and certified shift supervisors, respectively. The secure-hours clause was also tightened up. Members only got a small bonus payment on ratification. Tellingly for the company, our membership went from 700 in March 2008 to 1364 in March 2009.

Another two-year agreement was signed in September 2011 (backdated to February) for 2011-13, again without a major dispute. For the first time, it included a clause requiring payment of an additional 15 minutes if the paid break is missed for some reason. Importantly, it retained previous wage relativities above minimum wage for all graded positions. A new targeted scheduled hours protocol was adopted to limit wide fluctuations of employees work hours by ensuring staff who average at least 25 hours will not be reduced by more than 25%. But whilst improvements were being made, McDonald’s remained behind the terms of the Restaurant Brands agreement, by 50 cents per hour up to $3 per hour for more experienced staff.

In 2013, we were determined to close the gap and try and win the member-only benefit package.

McDonald’s delegates training day at Unite Union office Auckland.

Negotiations broke down on April 30, so the campaign began with a May Day protest outside a central Queen St McDonald’s store owned by one of the largest franchisees. A union delegate from this franchisee’s store had also been told “don’t act gay” or he would be disciplined. This threat became an international media event before it was reported in New Zealand. The worker was later sacked after supplying us the evidence during the dispute on unpaid breaks being missed and after he appeared before a parliamentary select committee on September 11, 2013 discussing the government’s planned removal of many legal protections for breaks. He has received compensation from McDonald’s mediated by the Human Rights Commission for the anti-gay discrimination, but we are scheduled to have a mediation over the dismissal. We have also complained to the parliamentary select committee discussing the employment law changes because we believe his comments to it should have been protected.

The heavy policing of the Queen Street protests in Auckland during the 2013 dispute resulted in us discovering that police still received a 50% discount on all purchases from McDonald’s. The cash register even had a special “police” button. Following a complaint by the union, the Commissioner of Police ordered all police staff to stop accepting the discount upon threat of dismissal. The Auckland District Commander later spoke with Joe Carolan and myself and gave a sort-of apology for the police methods.

Police guard McDonald’s Queen St store during 2013 dispute.

An agreement was finally signed after five months of skirmishes from one end of the country to the other. It can best be described as a draw this time. The geographical spread of the dispute was greater than 2006 and 2008, but the membership engagement was not as strong – maybe due to the growth in unemployment in recent years. We didn’t close the gap, but we fended off some take-back demands from the company to reintroduce youth rates and weaken the breaks clauses. We strengthened the secure-hours clauses whereby the employer has to issue a notice when thinking of hiring new staff, and we created an appeals process for workers believing they had been unfairly treated, with an obligation on the company to share relevant information. During the dispute, we also discovered that workers often missed out on the unpaid 30-minute break they should have for working over a 4 hour shift. This is the subject of a legal action by Unite against the company.

One significant advance from the union’s viewpoint is that for the first time, the collective agreement is a completely different document to that of the individual employment agreement used by the company. It is also half the length without the company propaganda.

BK go on the counter attack

We remained weakest at BK in membership numbers and engagement. This put constraints on what we could negotiate and how effectively we could enforce the agreement. The main problem was that agreed steps whereby employees could be trained and obtain increases over the minimum wage never materialised in practise. Eighty per cent of staff remain on the minimum wage and have few hopes of getting off. This did not mean that other improvements weren’t made. We won secure hours clauses similar to those in the other collectives. We got 15-minute paid breaks. In 2009, we even won a modest redundancy agreement for the first time in the industry (2 weeks pay for the first year of service and one week’s pay for each subsequent year). In February 2011, BK tried to sack Julie Tyler a delegate for making a Facebook comment that “Real jobs don’t underpay and overwork people like BK does”. A public campaign blocked the sacking.

BK workers stage silent protest outside store against company anti-union tactics during 2012.

In 2012, BK went on the offensive in a concerted drive to eliminate the union. Our membership was cut from about 500 to 300. We couldn’t legally take industrial action at that time, so we went on a name and shame publicity drive exposing some home truths about BK. This included the fact that the company was keeping 80% of their staff on minimum wages, exploiting migrant workers flagrantly and ignoring health and safety concerns. The gods were on our side that month because our campaign coincided with some media and community groups putting the spotlight on migrant workers’ abuse. We succeeded in ensuring that BK was in the frame. Workers and managers supplied us with email evidence of the company drive, including targets it has set for reducing union membership in each store. By the end of our campaign, BK admitted to suffering a significant loss of customers and reduction in sales. As a result, they asked for a peace settlement that included compensation for all union members at BK.

We remain weaker there compared to the other major companies, but today we have more members than ever before and we are making headway with migrant groups who, along with other workers, have more confidence we can protect them. Next year, we will be in a better position to tackle the wage gap with the other chains.

Some attacks on Unite

As mentioned earlier, there was some sectarianism towards Unite at the beginning by some Labour Party members and union officials. In a very few places, ourselves and the SFWU “compete” for the same membership – at one hotel, the Casino and two security companies. That inevitably involves some friction, but we do joint agreements at the hotel and the Casino without major problems.

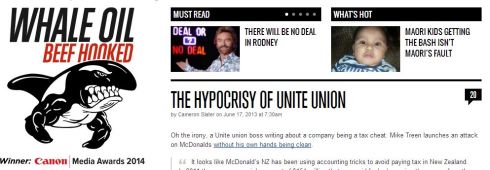

Right wing bloggers have focused their attacks not on what we do but on the alleged tax problems we have.

Unite was formed with no financial resources. We spent before we received fees. We always had an ambitious growth strategy. We occasionally hired new staff optimistically in anticipation of growth. Matt McCarten formed a company to manage the relationship with Te Wananga o Aotearoa which made a profit and was able to subsidise some of our activities. Unfortunately, Matt fell very ill with two different cancers from which he was not expected to live. Some of the projects subsidising Unite fell by the wayside. Matt actually had a life insurance policy which had the union as a beneficiary, and needless to say, financial affairs could not be top priority for Matt at the time.

Rather than sack staff, we let a debt build up with the tax man for a period. That has since been repaid. We still have an overdraft, but our accounts this year show assets exceeding liabilities for the first time in our existence. We have an income of over $1 million in fees and close to half a million dollars in benefit fund contributions. Income exceeds expenditure and the overdraft should be eliminated early next year. Without the tax issue to try and damage our reputation, the main right wing blogger, “Whale Oil”, has been reduced to a pathetic criticism that our current fee structure penalised the poorest members because we had a minimum fee of $2 a week with a 1.1% rate up to $5.75 a week maximum in companies where we have a collective agreement. This is a modest fee structure in anyone’s language. He also ignored that a large proportion of our members receive additional benefits that non-members do not. This more than compensates many union members for the fees they pay.

2015 – year for secure hours

All the main fast food agreements are to be renegotiated in early 2015. We have told each employer that we expect to make progress on the area of secure hours. We see no way around the issue other than to have some form of minimum guaranteed hours for staff – at least after an initial period of employment.

We have clauses in all the fast food agreements that are designed to protect existing staff by offering available hours to them before hiring new staff. But managers often ignore this requirement if they can. To counter this, we have added clauses that hours available must be put on a notice board before staff are hired. Other clauses allow the union to get involved and have access to information needed, like rosters, to determine if the shift allocation is fair. But we still find these clauses being violated again and again. It is almost impossible to police effectively unless the store has a very good union culture. Some do, but they are the minority. Guaranteed hours seems to be the only solution. We are fortunate that other unions are waking up to the danger of what have been dubbed “zero-hour contracts”. It is possible that we can fight this scourge of the working class as part of a broader union campaign.

If the government changes in the election scheduled for September 20 this year, we will be in a much stronger position. The opposition parties have proposed to raise the minimum wage from $14.25 to $15.00 before Xmas and to increase by another dollar on April 1, 2015 – the usual date for minimum wage changes. We simply have to make sure the margins are applied above the minimum wage which sets the start rates in our contracts, and then focus on improving the hours workers obtain. It is the hours of work, as much as the rate you get paid, that determines if you can pay your rent.

What lessons can we draw from the Unite experience

Unions need new approaches to succeed in the kinds of industries we’re talking about. The traditional approach of recruiting union members one by one over a prolonged period can’t work in these industries because the boss can find out where that’s going on and bully people out of it. Workers often aren’t in these jobs for long enough for that slow accumulation of union members to work or make a difference. You need public, political campaigns that provide protection for workers and gives workers confidence you mean business. The union has to be framework for workers to find their voice and lead struggles.

Sit down on Queen Street, Auckland, during 'SupersizeMyPay' campaign.

It has to be all-or-nothing. “Supersize My Pay” was a public, political campaign against the fast food companies which exposed them as exploiters in any way we could. We went after their “brand” which they value above all else. We brought the community in to give public support and prevent victimisation. When those approaches gained momentum, workers started to gain confidence that maybe the risk of standing up for themselves is worth it. That’s the key question – how do you build that confidence?

The campaign needs ambitious goals to make the fight worthwhile. It also needs to combine an industrial campaign with a political campaign around issues like lifting the minimum wage and getting rid of youth rates.

Our modern, industrial unions emerged decades ago out of new models of industry-wide organising which broke away from the narrow craft unions of the day. There are some major differences in size between the industries where those unions were based and the key economic sectors in western countries today–such as retail, service and finance. But a large call centre in New Zealand might have 500 workers or more — which in New Zealand terms is a pretty big workplace. McDonald’s employs almost 10,000 workers – it’s one of the biggest private-sector employers in the country. Those workers are young workers, migrant workers, semi-casualised workers. Those are the people producing profit for the capitalist class in New Zealand today. That’s the working class!

The bottom line is that organising in these industries, where more and more of the working class, and particularly the young working class, in western countries is now employed, has to be done — by any means necessary.

What has Unite achieved?

One of the principle achievements of the Unite effort over the past decade has been maintaining an ongoing, organised presence in industries that suffer a huge turnover of staff. Annual turnover of staff in the industries we represent was, until recently, 100%. It has dropped somewhat due to the 2008-10 recession. Our membership turnover is similar. We have to recruit 5000 members a year to maintain our current size of 7000. Unite is a fast food union. 3500 of our 7000 fee-paying members are fast food workers. The important thing to note however is that we have succeeded in doing it year in and year out in industries like fast food for almost a decade.

We also have a contract with the largest casino in the country. We have contracts with the two biggest hotel chains (Accor and MCK) in the country. We have expanded our presence in security and call centres.

We invest significant resources to having an annual national delegates conference of 150 mostly young fighters from around the country. Union officials from unions representing workers as apart as teachers, public servants or bank workers have praised Unite for giving many of their members a positive first taste of unionism.

Unite national delegates conference 2012.

Major challenges remain before us. Can we extend our presence in the fast food industry – especially the franchise-dominated companies? How can we deal with the problem that hundreds of Pizza delivery drivers are on self-employed contracts which we cannot legally represent? What new sectors can we look to for an organising drive? Can we resolve the contradictions between what is dubbed a “servicing model” versus and “organising model” in high turnover industries? Does Unite have a “model” at all beyond doing what seems to work?

It is true that we have had some special circumstances working in our favour. But we still have to convince thousands of young workers in a 24/7 business to join a union and pay fees by speaking to them and getting them to sign a membership form. We have done this with no financial help from the broader union movement. We did it with volunteers, credit cards and low paid staff, when we could even pay. It a success worth celebrating and where possible emulating.

Unite is also now not alone in doing this type of union building in New Zealand today. First Union in particular has used many of our campaigning techniques (and some of our former staff!) to launch successful recruitment drives in major non-union retail chains like The Warehouse and the Pak ‘n’ Save supermarket chain.

A rejuvenated labour movement with the unions at their heart is vital for the future of the working class. To be successful, we need to become a social movement that has a radical critique of the system we live under, a strong social justice program, and inspiring methods to challenge and change the unequal and exploitative society we are forced to live under today. Unite remains committed to playing its part in sowing the seeds for the regeneration of a labour movement that can play its natural role as leader of a society-wide movement to change the world for the better.

Unite organiser Joe Carolan on Unite truck.