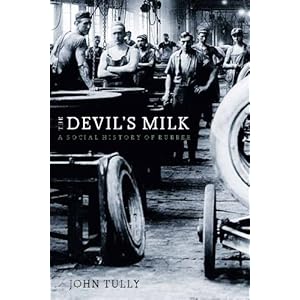

`Coolie revolts': exclusive excerpt from 'The Devil's Milk: A social history of rubber'

The Devil’s Milk: A social history of rubber

By John Tully

Monthly Review Press, 2011

March 13, 2011 – With the kind permission of Monthly Review Press, Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal is honoured to be able to bring its readers an exclusive excerpt from Australian socialist John Tully's fascinating new book, The Devil’s Milk: A social history of rubber. The section below details how the peoples of the colonies exploited by the imperialist rubber barons fought back against their oppression. Links readers are urged to purchase a copy of this excellent new book. See also an interview with John Tully about his new book, "New book reveals the history of rubber: holocausts, environmental destruction and class struggle".

Order the The Devil’s Milk from Monthly Review Press HERE.

By John Tully

The plantation system was based on the super-exploitation of labour. Pay was so low that the English assistant Leopold Ainsworth wondered how the Tamil workers and their families could “possibly exist as ordinary human beings” on the wages paid on his boss’s Malayan plantation.

In 1926, the cost of a Papuan indentured laborer was 20 per cent of that of a white worker, 25 per cent of that of an employed estate manager, and 10 percent of that of a white unskilled laborer. Racist humiliation, insult, and cruelty were part of the everyday lives of the coolies: “I’ve been greeted only with cudgels/And a pot-bellied, red-faced French colon/Who swears all day long: ‘shit, pig, scum!’” laments a Vietnamese vè poem about work in the colonial era.

The plantation workforces were largely made up of new proletarians from a peasant background. Peasants often tend toward individualistic solutions to socially based problems. Moreover, these peasants-turned-workers often came from outside the regions where the rubber estates were situated. In the case of Sumatra and Malaya in particular, the new plantation proletariat was ethnically heterogeneous, riven by barriers of language, culture, and belief. In addition, many of the workers were transient and would return to their homes upon the expiration of their contracts, although as the present-day ethnic composition of Singapore and Malaya shows, many of them stayed on in their adopted countries.

Class consciousness and the internationalist values of the labour movement have to be learned, and the classic forms of workers’ resistance often have to be reinvented afresh. While stoical fatalism might be an understandable response to factors beyond an individual’s control in a traditional setting, in the plantation context it was a barrier to collective action. The uprooted peasant might also regard cruelty and injustice as a normal part of life to be endured, or even as somehow justified.

When Sir Maori Kiki, a future prime minister of independent Papua New Guinea, was a boy in both senses of the word, a white planter poured a cup of scalding hot tea over his chest because Kiki had accidentally slopped some in the saucer. Kiki was scarred for life but, “At the time,” writes Hank Nelson, “He accepted the punishment. That was the way things were. It was only later when he was filled with hate.”

Continue reading on screen below or download the excerpt (PDF) here.

‘Coolie revolts': exclusive excerpt from The Devil's Milk: A social history of rubber