Foreign direct investment: The opium for development

[Editor’s note: The research for this paper was conducted jointly with Russian Marxist Boris Kagarlitsky, who today is in a Russian prison due to his anti-war views. You can support the campaign to free Kagarlitsky by signing a petition here.]

This month, I presented our research (with Boris Kagarlitsky), at the annual meeting of the Armenian Economic Association in Yerevan. Our research applies a Marxist perspective on the relationship between foreign direct investment (FDI) and economic dependency in the Open Balkan countries (Albania, North Macedonia and Serbia). For the occasion in Yerevan, we also included data for Armenia using the same methodology.

One of the explicit objectives of the Open Balkan is to attract foreign investments. As we discovered in Armenia, attracting foreign investments is also very high on that country’s political agenda. This is because mainstream economics claims that developing countries are caught in a low-equilibrium trap due to a lack of capital. FDI is therefore seen as a critical factor of capital accumulation for growth and poverty reduction (Sachs, 2005).

Unmasking the illusion of growth

However, our study found that hopes of accelerating development in post-socialist countries with foreign investment are ill-justified. Our research demonstrates that, rather than contributing to capital accumulation, foreign investment has enabled value transfer and capital disaccumulation in the Open Balkan region (and elsewhere in the world), exacerbating external budget deficits, increasing capital outflows, and crowding out domestic investment. A one percent increase in FDI in the Open Balkan inflows is correlated with a drop in the external balance by 0.30 percentage points, an increase of FDI outflows by 0.13 percentage points, and displacement of domestic investment in total gross domestic investment by 3.75 percentage points.

Dependency confirmed: The Open Balkan case

These outcomes confirm the dependent and peripheral status of the Open Balkan and highlight the overall negative impact of FDI on the economic independence of its member countries, in accordance with Marxist dependency theory (Amin, 1974; Marini, 2022). This theory posits that foreign financial flows to peripheral regions are structured to extract and transfer economic surplus, rather than fostering local development. In the words of Karl Marx (1971: 364), “Capital is sent abroad not because it cannot be applied at home, but because it yields higher profits elsewhere.” If religion is the opium of the people, FDI is the opium of development: it creates an appearance of development while undermining and restricting development opportunities.

The GDP mirage and Armenia’s FDI paradox

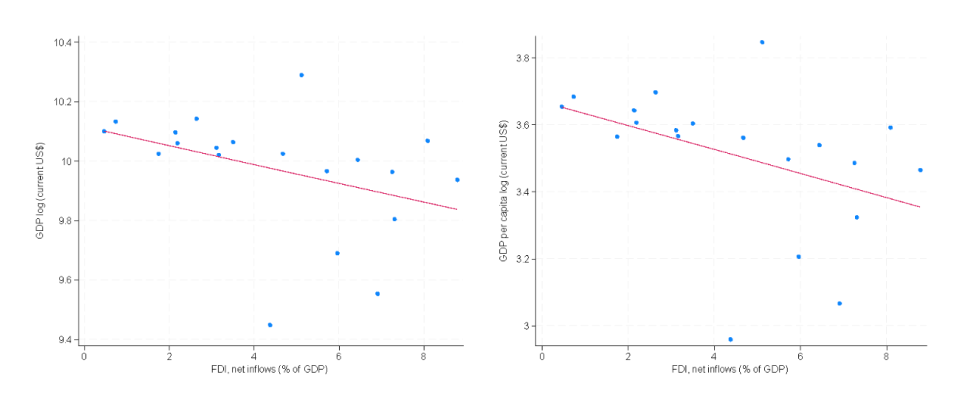

Our research deliberately avoids examining the impact of FDI on economic growth. This decision is rooted in the argument that GDP, as a measure of development, is imperfect and potentially misleading (Stiglitz et al., 2009). The relationship between FDI and economic development remains a contentious topic with contradictory empirical findings. While GDP growth in the Open Balkan region is positively correlated with FDI inflows (Chart 1), this correlation does not equate to increased economic independence.

Although statistically significant for annual GDP growth at 0.05, the growth observed does not improve economic quality as measured by dependency indicators in our study. This situation exemplifies what Seers (1969) describes as “growth without development,” where economic growth fails to address social and political issues and can even exacerbate them.

The situation is even starker in Armenia where FDI inflows correlate with negative growth in a statistically significant way (Chart 2). A one percent increase in FDI in Armenia is correlated with a drop in the external balance by 1.47 index points, an increase of FDI outflows by 0.25 percentage points, and displacement of domestic investment in the total gross domestic investment by 2.05 percentage points.

Trapped by external interests

Peripheral countries face significant constraints in mitigating the harmful effects of FDI due to limited decision-making space, capacity, and often political will, despite advancements in institutional environments such as corruption control (Amin, 1974 Katz, 2022). The latter finding is quite surprising: better control of corruption results not in the improvement, but in the deterioration of dependency. Specifically, better control of corruption is negatively correlated with the terms of trade and external balance of the periphery countries (Pozhidaev, 2024).

This raises the question of “fighting corruption for what?” If less corruption attracts more FDI (as mainstream economics maintains), then less corruption may well result in inferior development outcomes. Countries on the receiving end of FDI, driven by external interests, often find themselves choosing between imperfect investments and no investments at all. These investments frequently come with substantial political pressure from external entities, as illustrated by the proposed lithium exploitation project in Serbia, which has raised significant environmental concerns.

Revolution or reform?

When asked in Yerevan “What should we do then?”, our answer was “Do a socialist revolution.” Only a radical social change that sets labour free and puts the productive forces at the service of the society at large, rather than a bunch of (foreign and comprador) capitalists, can ensure conditions for sustained and sustainable development.

In the absence of the immediate prospects for this development, our study underscores the critical need for peripheral countries to strengthen their agency in FDI decision-making, despite the constrained manoeuvring space within the global capitalist structure. This aligns with Kagarlitsky's (2008) observations on the limitations imposed by the global capitalist system on peripheral countries.

FDI promotion policies should support national development strategies aimed at addressing “economic disarticulations” (Amin, 1974), where economic sectors engage in marginal exchanges primarily with the outside world rather than internally. For FDI to contribute to greater economic independence and quality growth, it must introduce new goods, technologies, and human capital into economies lacking the necessary know-how or resources, as suggested by the endogenous growth model (Romer, 1994). When FDI enters sectors with competing domestic firms or firms already producing for export markets, it can displace domestic investment opportunities, an effect identified in our study.

Responsible investment management

Effective public investment management is essential to structuring and implementing FDI projects in a way that minimises waste and maximises public benefits. Addressing inefficiencies in public investment processes, which the IMF (2015) estimates average around 30 percent, could yield significant economic dividends. The most efficient public investors achieve twice the growth impact from their investments compared to the least efficient. Sharing the rewards of FDI projects through public shareholding can result in high social benefits and reduced capital outflows (Laplane and Mazzucato, 2020). This idea resonates with Kagarlitsky's (2014) critique of neoliberalism and the importance of state intervention in achieving equitable economic development.

Furthermore, our study highlights the importance of coordinated FDI policies within the Open Balkan region to foster quality growth and reduce dependency. Strong and effective intergovernmental planning and coordination are necessary to address coordination failures (Rodrik, 1996) and capitalise on the economies of scale that the Open Balkan initiative aims to create. This does not imply equalising FDI across countries, which is a major concern for their politicians, but rather ensuring equal benefits from intensifying existing and creating new regional forward and backward linkages through strategic complementarity in investment decisions (Krugman, 1997).

A holistic approach that includes robust public investment management, strategic coordination of FDI policies, and an emphasis on introducing new technologies and human capital is required. By tackling these issues, the Open Balkan countries can better harness FDI for sustainable development and economic resilience — but only to the extent that global capitalism permits.