The place of capital exports in Lenin’s conception of imperialism — A response to John Bellamy Foster

In a recent article in Monthly Review (Volume 76, Number 6, November 2024), “The New Denial of Imperialism on the Left”1, John Bellamy Foster argued:

A common economistic error advanced primarily by Western Marxist theorists has been to suggest, without any real backing, that Lenin saw imperialism as a product of the export of capital, or that it had its cause in economic crisis theory [sic] of some sort, either underconsumption or the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. In contrast, Lenin himself, in fact, argued that imperialism was the monopoly stage of capitalism and was thus as basic to the system as the search for profits. It thus needed no special economic explanation. (Bellamy Foster 2024, endnote 12)

The article as a whole, whatever other virtues it might or might not have, exhibits this odd perspective. In particular, Bellamy Foster’s claim concerning the export of capital is plainly wrong, as the following excerpts from Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (Lenin 1916) demonstrate. The export of capital was, to Lenin’s mind, an exceptionally important part of what was, in every respect, a special economic explanation: ‘the connection and relationships between the principal economic features of imperialism’, as he put it (1916, p. 641). The excerpts are long — forgivably, I hope — but I think it best to let Lenin speak for himself. In addition, the excerpts double — usefully, again I hope — as a selective précis of Imperialism.

After the section “Lenin in his own words”, I shall try to distill his conception of the principal economic features of imperialism and briefly refer to the questions of underconsumption and the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. I should add that this contribution is not a defence of Lenin’s conception. Rather, it is an appeal for accuracy in describing it. As Lenin said in Imperialism, facts are stubborn things. Textual facts are especially stubborn because they remain in print.

Lenin in his own words

All page references for the following excerpts are from Lenin, 1916, Imperialism, The Highest Stage of Capitalism, in V.I. Lenin: Selected Works in Three Volumes, Volume 1, Progress Publishers 1976, Moscow, pp. 641-731. This source is freely available to readers due to the indefatigable scholarly work of the Marxists Internet Archive.2 All italicised emphases in this section are from the original text. As noted above, my choice of excerpts is selective. The selection as a whole is best described as “hoping to be comprehensive, with particular reference to the export of capital.”

Context: From two Prefaces

The pamphlet here presented to the reader was written in the spring of 1916, in Zurich. In the conditions in which I was obliged to work there I naturally suffered somewhat from a shortage of French and English literature and from a serious dearth of Russian literature. However, I made use of the principal English work on imperialism, the book by J.A. Hobson, with all the care that, in my opinion, that work deserves. This pamphlet was written with an eye to the tsarist censorship. Hence, I was not only forced to confine myself strictly to an exclusively theoretical, specifically economic analysis of facts, but to formulate the few necessary observations on politics with extreme caution, by hints, in an allegorical language — in that accursed Aesopian language — to which tsarism compelled all revolutionaries to have recourse whenever they took up the pen to write a “legal” work. It is painful, in these days of liberty, to re-read the passages of the pamphlet which have been distorted, cramped, compressed in an iron vice on account of the censor … In order to show the reader, in a guise acceptable to the censors, how shamelessly untruthful the capitalists and the social-chauvinists who have deserted to their side (and whom Kautsky opposes so inconsistently) are on the question of annexations; in order to show how shamelessly they screen the annexations of their capitalists, I was forced to quote as an example — Japan! The careful reader will easily substitute Russia for Japan, and Finland, Poland, Courland, the Ukraine, Khiva, Bokhara, Estonia or other regions peopled by non-Great Russians, for Korea. I trust that this pamphlet will help the reader to understand the fundamental economic question, that of the economic essence of imperialism, for unless this is studied, it will be impossible to understand and appraise modern war and modern politics. (Preface, Petrograd, April 26 1917, pp. 634-5)

It is precisely the parasitism and decay of capitalism, characteristic of its highest historical stage of development, i.e., imperialism. As this pamphlet shows, capitalism has now singled out a handful (less than one-tenth of the inhabitants of the globe; less than one-fifth at a most “generous” and liberal calculation) of exceptionally rich and powerful states which plunder the whole world simply by “clipping coupons”. Capital exports yield an income of eight to ten thousand million francs per annum, at pre-war prices and according to pre-war bourgeois statistics. Now, of course, they yield much more. Obviously, out of such enormous superprofits (since they are obtained over and above the profits which capitalists squeeze out of the workers of their “own” country) it is possible to bribe the labour leaders and the upper stratum of the labour aristocracy. And that is just what the capitalists of the “advanced” countries are doing: they are bribing them in a thousand different ways, direct and indirect, overt and covert.’ (Preface to the French and German editions July 6 1920, pp. 640)

I shall try to show briefly, and as simply as possible, the connection and relationships between the principal economic features of imperialism. I shall not be able to deal with the non-economic aspects of the question, however much they deserve to be dealt with. (p. 641)

Monopoly, banks and finance capital

Half a century ago, when Marx was writing Capital, free competition appeared to the overwhelming majority of economists to be a “natural law” … [Marx] proved that free competition gives rise to the concentration of production, which, in turn, at a certain stage of development, leads to monopoly…But facts are stubborn things, as the English proverb says, and they have to be reckoned with, whether we like it or not. The facts show that differences between capitalist countries, e.g., in the matter of protection or free trade, only give rise to insignificant variations in the form of monopolies or in the moment of their appearance, and that the rise of monopolies, as the result of the concentration of production, is a general and fundamental law of the present stage of development of capitalism. (p. 645)

As banking develops and becomes concentrated in a small number of establishments, the banks grow from modest middlemen into powerful monopolies having at their command almost the whole of the money capital of all the capitalists and small businessmen and also the larger part of the means of production and sources of raw materials in any one country and in a number of countries. This transformation of numerous modest middlemen into a handful of monopolists is one of the fundamental processes in the growth of capitalism into capitalist imperialism; for this reason, we must first of all examine the concentration of banking … The change from the old type of capitalism, in which free competition predominated, to the new capitalism, in which monopoly reigns, is expressed, among other things, by a decline in the importance of the Stock Exchange … Again and again, the final word in the development of banking is monopoly. As regards the close connection between the banks and industry, it is precisely in this sphere that the new role of the banks is, perhaps, most strikingly felt … The result is, on the one hand, the ever-growing merger, or, as N.I. Bukharin aptly calls it, coalescence, of bank and industrial capital and, on the other hand, the growth of the banks into institutions of a truly “universal character” … Thus, the twentieth century marks the turning-point from the old capitalism to the new, from the domination of capital in general to the domination of finance capital. (pp. 653, 660, 662, 664, 666)

“A steadily increasing proportion of capital in industry”, Hilferding writes, “ceases to belong to the industrialists who employ it. They obtain the use of it only through the medium of the banks which, in relation to them, represent the owners of the capital. On the other hand, the bank is forced to sink an increasing share of its funds in industry. Thus, to an ever-greater degree the banker is being transformed into an industrial capitalist. This bank capital, i.e., capital in money form, which is thus actually transformed into industrial capital, I call ‘finance capital’ … Finance capital is capital controlled by banks and employed by industrialists” … Hilferding [also] stresses the part played by capitalist monopolies. The concentration of production; the monopolies arising therefrom; the merging or coalescence of the banks with industry — such is the history of the rise of finance capital and such is the content of that concept. We now have to describe how…the “business operations” of capitalist monopolies inevitably lead to the domination of a financial oligarchy … Paramount importance attaches to the “holding system” [ownership by parent companies of subsidiaries]. (pp. 666-7)

The extraordinarily high rate of profit obtained from the issue of bonds, which is one of the principal functions of finance capital, plays a very important part in the development and consolidation of the financial oligarchy. “There is not a single business of this type within the country that brings in profits even approximately equal to those obtained from the floatation of foreign loans,” says Die Bank … It is characteristic of capitalism in general that the ownership of capital is separated from the application of capital to production, that money capital is separated from industrial or productive capital, and that the rentier who lives entirely on income obtained from money capital, is separated from the entrepreneur and from all who are directly concerned in the management of capital. Imperialism, or the domination of finance capital, is that highest stage of capitalism in which this separation reaches vast proportions. The supremacy of finance capital over all other forms of capital means the predominance of the rentier and of the financial oligarchy; it means that a small number of financially “powerful” states stand out among all the rest. The extent to which this process is going on may be judged from the statistics on emissions, i.e., the issue of all kinds of securities. (pp. 673, 677)

From these figures we at once see standing out in sharp relief four of the richest capitalist countries, each of which holds securities to amounts ranging approximately from 100,000 to 150,000 million francs. Of these four countries, two, Britain and France, are the oldest capitalist countries, and, as we shall see, possess the most colonies; the other two, the United States and Germany, are capitalist countries leading in the rapidity of development and the degree of extension of capitalist monopolies in industry. Together, these four countries own 479,000 million francs, that is, nearly 80 per cent of the world’s finance capital. In one way or another, nearly the whole of the rest of the world is more or less the debtor to and tributary of these international banker countries, these four “pillars” of world finance capital. It is particularly important to examine the part which the export of capital plays in creating the international network of dependence on and connections of finance capital. (p. 678)

Export of capital

Typical of the old capitalism, when free competition held undivided sway, was the export of goods. Typical of the latest stage of capitalism, when monopolies rule, is the export of capital. (p. 678)

On the threshold of the twentieth century we see the formation of a new type of monopoly: firstly, monopolist associations of capitalists in all capitalistically developed countries; secondly, the monopolist position of a few very rich countries, in which the accumulation of capital has reached gigantic proportions. An enormous “surplus of capital” has arisen in the advanced countries. It goes without saying that if capitalism could develop agriculture, which today is everywhere lagging terribly behind industry, if it could raise the living standards of the masses, who in spite of the amazing technical progress are everywhere still half-starved and poverty-stricken, there could be no question of a surplus of capital. This “argument” is very often advanced by the petty-bourgeois critics of capitalism. But if capitalism did these things it would not be capitalism; for both uneven development and a semi-starvation level of existence of the masses are fundamental and inevitable conditions and constitute premises of this mode of production. As long as capitalism remains what it is, surplus capital will be utilised not for the purpose of raising the standard of living of the masses in a given country, for this would mean a decline in profits for the capitalists, but for the purpose of increasing profits by exporting capital abroad to the backward countries. In these backward countries profits are usually high, for capital is scarce, the price of land is relatively low, wages are low, raw materials are cheap … The need to export capital arises from the fact that in a few countries capitalism has become “overripe” and (owing to the backward state of agriculture and the poverty of the masses) capital cannot find a field for “profitable” investment … [T]he export of capital reached enormous dimensions only at the beginning of the twentieth century. Before the war the capital invested abroad by the three principal countries amounted to between 175,000 million and 200,000 million francs. At the modest rate of 5 per cent, the income from this sum should reach from 8,000 to 10,000 million francs a year — a sound basis for the imperialist oppression and exploitation of most of the countries and nations of the world, for the capitalist parasitism of a handful of wealthy states! (pp. 679-80)

The export of capital influences and greatly accelerates the development of capitalism in those countries to which it is exported. While, therefore, the export of capital may tend to a certain extent to arrest development in the capital-exporting countries, it can only do so by expanding and deepening the further development of capitalism throughout the world … Finance capital has created the epoch of monopolies, and monopolies introduce everywhere monopolist principles: the utilisation of “connections” for profitable transactions takes the place of competition on the open market. The most usual thing is to stipulate that part of the loan granted shall be spent on purchases in the creditor country, particularly on orders for war materials, or for ships, etc. In the course of the last two decades (1890-1910), France has very often resorted to this method. The export of capital thus becomes a means of encouraging the export of commodities. (p. 681)

Thus finance capital, literally, one might say, spreads its net over all countries of the world … The capital-exporting countries have divided the world among themselves in the figurative sense of the term. But finance capital has led to the actual division of the world. (p. 683)

Division of the world

Monopolist capitalist associations, cartels, syndicates and trusts first divided the home market among themselves and obtained more or less complete possession of the industry of their own country. But under capitalism the home market is inevitably bound up with the foreign market. Capitalism long ago created a world market. As the export of capital increased, and as the foreign and colonial connections and “spheres of influence” of the big monopolist associations expanded in all ways, things “naturally” gravitated towards an international agreement among these associations, and towards the formation of international cartels. This is a new stage of world concentration of capital and production, incomparably higher than the preceding stages. Let us see how this supermonopoly develops. (p. 683)

The capitalists divide the world, not out of any particular malice, but because the degree of concentration which has been reached forces them to adopt this method in order to obtain profits. And they divide it “in proportion to capital”, “in proportion to strength”, because there cannot be any other method of division under commodity production and capitalism. But strength varies with the degree of economic and political development. In order to understand what is taking place, it is necessary to know what questions are settled by the changes in strength. The question as to whether these changes are “purely” economic or non-economic (e.g., military) is a secondary one, which cannot in the least affect fundamental views on the latest epoch of capitalism. To substitute the question of the form of the struggle and agreements (today peaceful, tomorrow warlike, the next day warlike again) for the question of the substance of the struggle and agreements between capitalist associations is to sink to the role of a sophist. The epoch of the latest stage of capitalism shows us that certain relations between capitalist associations grow up, based on the economic division of the world; while parallel to and in connection with it, certain relations grow up between political alliances, between states, on the basis of the territorial division of the world, of the struggle for colonies, of the “struggle for spheres of influence”. (pp. 689-90)

Hence, we are living in a peculiar epoch of world colonial policy, which is most closely connected with the “latest stage in the development of capitalism”, with finance capital … The principal feature of the latest stage of capitalism is the domination of monopolist associations of big employers. These monopolies are most firmly established when all the sources of raw materials are captured by one group, and we have seen with what zeal the international capitalist associations exert every effort to deprive their rivals of all opportunity of competing, to buy up, for example, iron fields, oilfields, etc. Colonial possession alone gives the monopolies complete guarantee against all contingencies in the struggle against competitors, including the case of the adversary wanting to be protected by a law establishing a state monopoly. The more capitalism is developed, the more strongly the shortage of raw materials is felt, the more intense the competition and the hunt for sources of raw materials throughout the whole world, the more desperate the struggle for the acquisition of colonies … The interests pursued in exporting capital also give an impetus to the conquest of colonies, for in the colonial market it is easier to employ monopoly methods (and sometimes they are the only methods that can be employed) to eliminate competition, to ensure supplies, to secure the necessary “connections”, etc. The non-economic superstructure which grows up on the basis of finance capital, its politics and its ideology, stimulates the striving for colonial conquest. “Finance capital does not want liberty, it wants domination,” as Hilferding very truly says. (pp. 690, 695, 697)

A special stage

We must now try to sum up … capitalism only became capitalist imperialism at a definite and very high stage of its development … [the] main thing in this process is the displacement of capitalist free competition by capitalist monopoly … replacing large-scale by still larger-scale industry, and carrying concentration of production and capital to the point where out of it has grown and is growing monopoly: cartels, syndicates and trusts, and merging with them, the capital of a dozen or so banks, which manipulate thousands of millions. At the same time the monopolies, which have grown out of free competition, do not eliminate the latter, but exist above it and alongside it, and thereby give rise to a number of very acute, intense antagonisms, frictions and conflicts. Monopoly is the transition from capitalism to a higher system … If it were necessary to give the briefest possible definition of imperialism we should have to say that imperialism is the monopoly stage of capitalism … But very brief definitions, although convenient, for they sum up the main points, are nevertheless inadequate, since we have to deduce from them some especially important features of the phenomenon that has to be defined. And so, without forgetting the conditional and relative value of all definitions in general, which can never embrace all the concatenations of a phenomenon in its full development, we must give a definition of imperialism that will include the following five of its basic features: (1) the concentration of production and capital has developed to such a high stage that it has created monopolies which play a decisive role in economic life; (2) the merging of bank capital with industrial capital, and the creation, on the basis of this “finance capital”, of a financial oligarchy; (3) the export of capital as distinguished from the export of commodities acquires exceptional importance; (4) the formation of international monopolist capitalist associations which share the world among themselves, and (5) the territorial division of the whole world among the biggest capitalist powers is completed. Imperialism is capitalism at that stage of development at which the dominance of monopolies and finance capital is established; in which the export of capital has acquired pronounced importance; in which the division of the world among the international trusts has begun, in which the division of all territories of the globe among the biggest capitalist powers has been completed. We shall see later that imperialism can and must be defined differently if we bear in mind not only the basic, purely economic concepts — to which the above definition is limited — but also the historical place of this stage of capitalism in relation to capitalism in general … The characteristic feature of imperialism is not industrial but finance capital. It is not an accident that in France it was precisely the extraordinarily rapid development of finance capital, and the weakening of industrial capital, that from the eighties onwards gave rise to the extreme intensification of annexationist (colonial) policy … (1) the fact that the world is already partitioned obliges those contemplating a redivision to reach out for every kind of territory, and (2) an essential feature of imperialism is the rivalry between several great powers in the striving for hegemony, i.e., for the conquest of territory, not so much directly for themselves as to weaken the adversary and undermine his hegemony. (pp. 699-700, 702)

Parasitism and decay

As we have seen, the deepest economic foundation of imperialism is monopoly. This is capitalist monopoly, i.e., monopoly which has grown out of capitalism and which exists in the general environment of capitalism, commodity production and competition, in permanent and insoluble contradiction to this general environment. Nevertheless, like all monopoly, it inevitably engenders a tendency of stagnation and decay. Since monopoly prices are established, even temporarily, the motive cause of technical and, consequently, of all other progress disappears to a certain extent and, further, the economic possibility arises of deliberately retarding technical progress … Certainly, monopoly under capitalism can never completely, and for a very long period of time, eliminate competition in the world market (and this, by the by, is one of the reasons why the theory of ultra-imperialism is so absurd). Certainly, the possibility of reducing the cost of production and increasing profits by introducing technical improvements operates in the direction of change. But the tendency to stagnation and decay, which is characteristic of monopoly, continues to operate, and in some branches of industry, in some countries, for certain periods of time, it gains the upper hand. The monopoly ownership of very extensive, rich or well situated colonies operates in the same direction. Further, imperialism is an immense accumulation of money capital in a few countries, amounting, as we have seen, to 100,000-50,000 million francs in securities. Hence the extraordinary growth of a class, or rather, of a stratum of rentiers, i.e., people who live by “clipping coupons”, who take no part in any enterprise whatever, whose profession is idleness. The export of capital, one of the most essential economic bases of imperialism, still more completely isolates the rentiers from production and sets the seal of parasitism on the whole country that lives by exploiting the labour of several overseas countries and colonies…Great as this sum is, it [trade commissions] cannot explain the aggressive imperialism of Great Britain, which is explained by the income of £90 million to £100 million from “invested” capital, the income of the rentiers. The income of the rentiers is five times greater than the income obtained from the foreign trade of the biggest “trading” country in the world! This is the essence of imperialism and imperialist parasitism. For that reason the term “rentier state” (Rentnerstaat), or usurer state, is coming into common use in the economic literature that deals with imperialism. The world has become divided into a handful of usurer states and a vast majority of debtor states. (pp. 708-9)

Critique, history, self-determination

Imperialism is the epoch of finance capital and of monopolies, which introduce everywhere the striving for domination, not for freedom. Whatever the political system, the result of these tendencies is everywhere reaction and an extreme intensification of antagonisms in this field. Particularly intensified become the yoke of national oppression and the striving for annexations, i.e., the violation of national independence (for annexation is nothing but the violation of the right of nations to self-determination) … And shall we not be constrained to admit that the “fight” the Japanese is waging against annexations can be regarded as being sincere and politically honest only if he fights against the annexation of Korea by Japan, and urges freedom for Korea to secede from Japan? (pp. 725-6)

We have seen that in its economic essence imperialism is monopoly capitalism. This in itself determines its place in history, for monopoly that grows out of the soil of free competition, and precisely out of free competition, is the transition from the capitalist system to a higher socio-economic order. We must take special note of the four principal types of monopoly, or principal manifestations of monopoly capitalism, which are characteristic of the epoch we are examining. Firstly, monopoly arose out of the concentration of production at a very high stage. This refers to the monopolist capitalist associations, cartels, syndicates, and trusts … Secondly, monopolies have stimulated the seizure of the most important sources of raw materials, especially for the basic and most highly cartelised industries in capitalist society: the coal and iron industries … Thirdly, monopoly has sprung from the banks. The banks have developed from modest middleman enterprises into the monopolists of finance capital … Fourthly, monopoly has grown out of colonial policy. To the numerous “old” motives of colonial policy, finance capital has added the struggle for the sources of raw materials, for the export of capital, for spheres of influence, i.e., for spheres for profitable deals, concessions, monopoly profits and so on, economic territory in general … [Finally, m]ore and more prominently there emerges, as one of the tendencies of imperialism, the creation of the “rentier state”, the usurer state, in which the bourgeoisie to an ever-increasing degree lives on the proceeds of capital exports and by “clipping coupons”. (pp. 726-8)

Lenin’s conception of imperialism

Lenin (1916, p. 636, original emphasis) said that “the main purpose of the book was … to present … a composite picture of the world capitalist system in its international relationships at the beginning of the twentieth century.” To accomplish this, his task in part was to give an historical account, that is to locate in time when the composite conception of imperialism had actually matured (1916, p. 700, 726ff). In equal part, it was empirical: that is, to demonstrate factually that “capitalism has grown into a world system of colonial oppression and of the financial strangulation of the overwhelming majority of the population of the world by a handful of ‘advanced countries’” (1916, p. 637). In both respects, Imperialism is replete with source quotations and tables. Indeed, it overflows with “irrefutable bourgeois statistics” (1916, p. 636). However, for all that, it is no mere historical-empirical description. The composite picture it presents is economic, which is incomplete to be sure, but Lenin may be excused for narrowing the focus because the essence of imperialism is economic (1916, pp. 635, 641).

Very much as Marx had planned in Capital,3 Lenin aims to unfold each successive part of the composite picture of imperialism from more fundamental — that is, more abstract — parts that both precede it logically and are conceptually necessary for it. Each more concrete elaboration of the picture thus sits, or nests, within its more general predecessor and would be inconceivable otherwise. Monopoly would be an empty concept without the former concept of capitalism and its profit-making enlivening cause. Yet the more abstract, fundamental representations are insufficient by themselves. It is necessary to be progressively more complete, which is also to say to be more descriptively accurate, more concrete. Thus we see how profitable larger industrial enterprises dominate notionally “free” markets because of their greater productivity. The general idea or definition of capitalism thus requires more accurate specification as the form monopoly capitalism. Monopoly capitalism, in its turn, requires its own conceptual completion. Larger enterprises require the larger financial resources offered by correspondingly large monopolies in banking. Monopoly capitalism thus requires further specification as the form dominated by finance capital: that is, by a banking-industrial “financial” oligarchy. Ultimately, within this, sits the tendency towards a rentier state form. Lenin thereby both unfolds an increasingly composite picture and preserves more fundamental underlying concepts. In each new specification, as we can see, he embodies a causal mechanism. The dominance of finance capital is therefore the necessary consequence of motivating causes: profit, productivity, enterprise size and investment mass, etc.

Now, it is to the dangling “etc.” immediately above that we must attend in order to fully understand Lenin’s conception of imperialism. What are the motivating causes that take us from the mere (as it were) dominance of a banking-industrial “financial” oligarchy to the world carved up by a handful of advanced economies and their exploitation of the overwhelming majority of humanity? By itself, the preceding conception offers insufficient explanation. Specifically, what are the economic motives for the international extension of monopoly capitalism? Of course, the pre-existing colonial architecture had provided a platform (1916, p. 727), one enhanced by the early development of railways (1916, p. 679). More significant, to Lenin’s mind, were two motive forces, one essential, and the other contingent. The latter was the desire to secure reliable access to sources of the raw materials demanded by imperialism’s metropolitan industries. The former was the export of capital (1916, p. 728), made necessary by reduced domestic profitability and the immanent tendency of monopoly towards stagnation. Monopoly prices swell the coffers but simultaneously dampen the competitive necessity to invest relentlessly in productivity improvements (1916, p. 709). Though I might be accused of over-condensing the text, the following is a reasonable composite conclusion. Monopoly profits, stagnation, an unwillingness to invest in agriculture and the poverty of the masses together generate “an enormous surplus of capital”: that is, capital that “cannot find a field for ‘profitable’ investment” at home and that seeks the higher returns available in the poorer countries (1916, p. 679). This, in turn, drives the conquest of colonies: the desire to carve up the world into spheres of influence that both secure sources of raw materials and protect the investments that capital exports create (1916, pp. 695, 697). The notion of a surplus of capital is central to Lenin’s case.

Therefore, to say perfunctorily that “imperialism was the monopoly stage of capitalism” and “thus needed no special economic explanation” (Bellamy Foster 2024, endnote 12) would be like saying no more about capitalism than that it is “commodity production at its highest stage of development, when labour-power itself becomes a commodity” (1916, p. 678). This is true enough, as Marx maintained and Lenin echoed, but it is just the beginning of wisdom. Lenin, of course, does say more about imperialism than that it is “the monopoly stage of capitalism”, tout court. He says much more, especially about the export of capital. His definition, though he admits it to be less than adequate, is clear (1916, p. 700): “Imperialism is capitalism at that stage of development at which the dominance of monopolies and finance capital is established; in which the export of capital has acquired pronounced importance; in which the division of the world among the international trusts has begun, in which the division of all territories of the globe among the biggest capitalist powers has been completed.” A little further on, Lenin expands the definition by linking the “immense accumulation of money capital in a few countries” to the export of capital. Thus, the “world has become divided into a handful of usurer states and a vast majority of debtor states” (1916, p. 709). The “bourgeoisie to an ever-increasing degree lives on the proceeds of capital exports and by ‘clipping coupons’” (1916, p. 728).

Against this, we have Bellamy Foster’s assertion (2024, endnote 12) that “A common economistic error advanced primarily by Western Marxist theorists has been to suggest, without any real backing, that Lenin saw imperialism as a product of the export of capital.” Whether one is a “product” of the other is beside the point. The salient point is that the export of capital was, to Lenin, an essential aspect of his conception of imperialism. Of that, there can be no doubt. The question of whether or not Lenin thought that imperialism, presumably via the export of capital, “had its cause in economic crisis theory [sic] of some sort, either underconsumption or the tendency of the rate of profit to fall” (2024, endnote 12) is simply misplaced. First, we have seen how Lenin unfolded a nested composite picture, a composite including causalities irreducible to a single level or kind. A different and altogether more engaging question is whether one or other of underconsumption or the tendency of the rate of profit to fall might contribute to the cause of capital exports. Lenin’s remark concerning the “poverty of the masses” likely suggests that he saw a role for underconsumption. This was certainly the opinion of JA Hobson, upon whose work Lenin drew heavily (see the appended note). Secondly, underconsumption and the tendency of the rate of profit to fall are not merely crisis theories. The Western Marxist theorists to whom Bellamy Foster refers4 also regard them as causes of stagnation, which clearly makes them pertinent to this discussion.

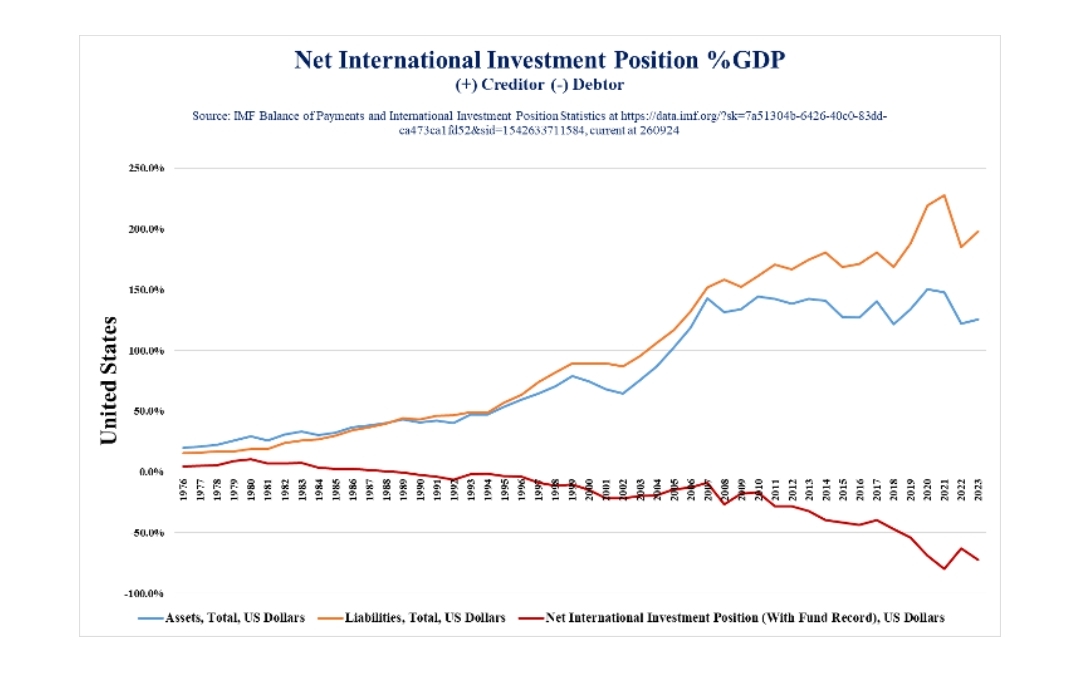

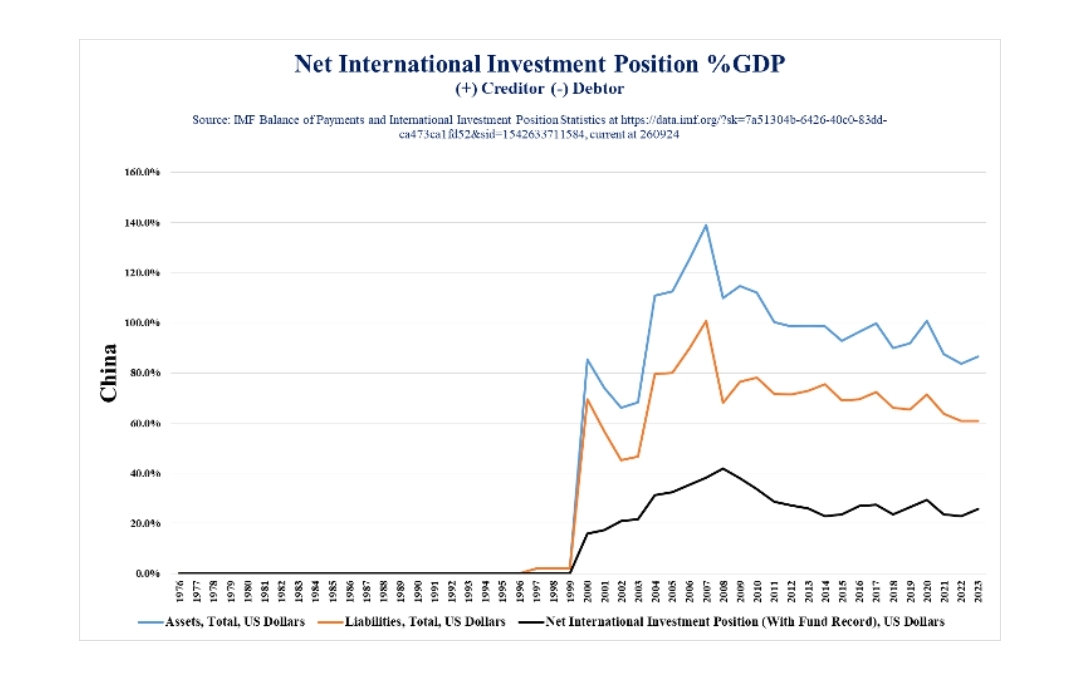

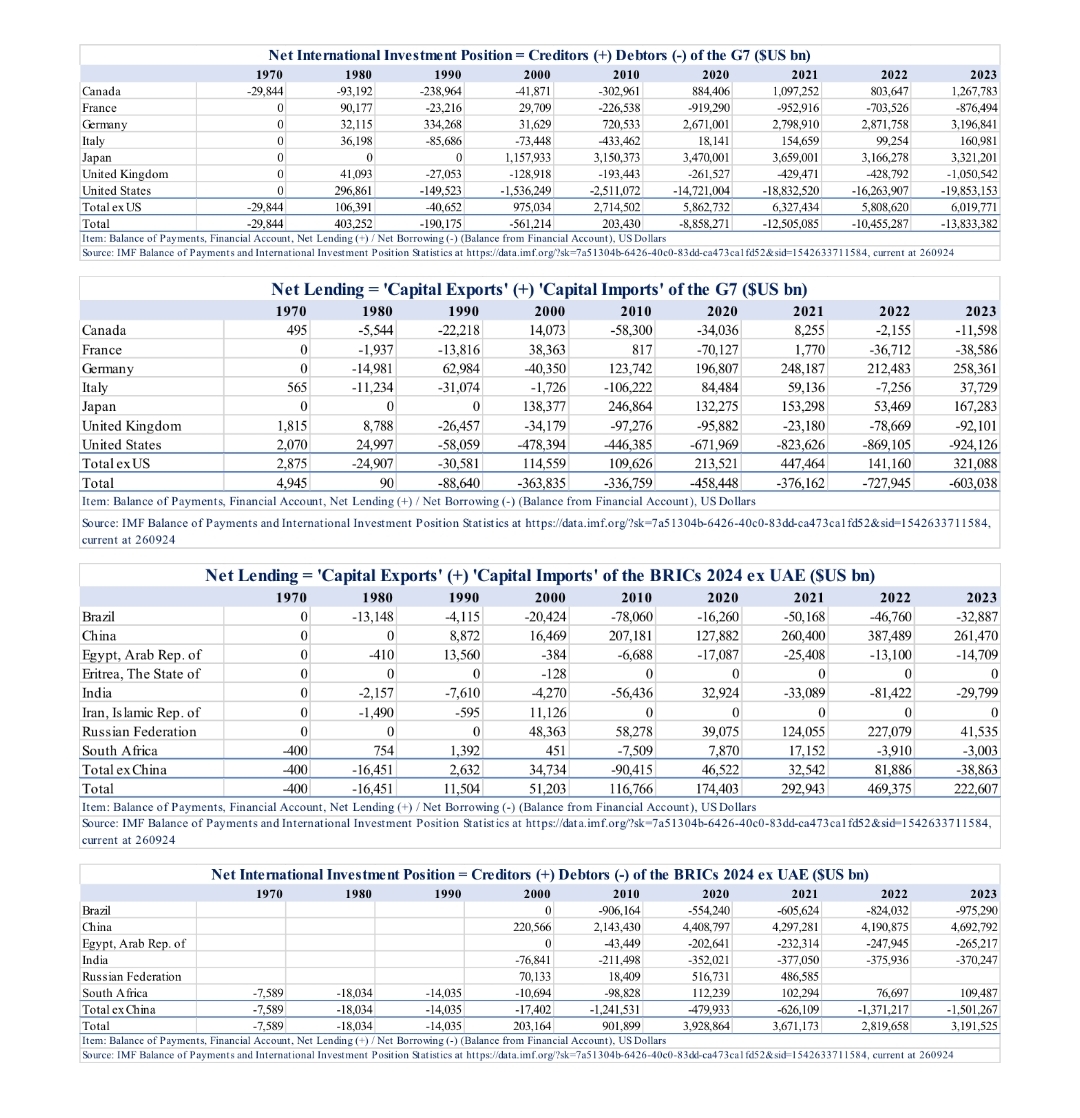

I should note for the record that I consider Lenin’s theory inadequate in many respects and plainly wrong in some. Obviously, a work penned in 1916 will also suffer empirically from the rigours of age. Now is not the time to air my claims.5 This contribution has been concerned to aid the current discussion of imperialism by trying to present Lenin’s views as they were, unsullied by retrospective reinterpretation. That said, it is hard to avoid thinking that any attempt to airbrush Lenin’s Imperialism — especially regarding the export of capital, the status of creditor and debtor nations and the like — is a form of avoidance behaviour in the face of awkward but stubborn facts. The US, for example, has for some years been the world’s largest importer of capital and debtor nation. China is now one of the world’s largest capital exporters and creditor nations. Other nations that are members of the G7 and the BRICs, respectively, present a mix. The two charts and four tables below illustrate some of the facts.6

Of course, the peril of deliberate or inadvertent misinterpretation stalks any contribution to this discussion. For the record, I am not saying that the US has ceased to be “imperialist” and that China has taken its place. I am saying that the discussion needs to recognise the facts such as they are and to account for them rigorously in theory.

Appendix: A note on JA Hobson’s Imperialism

The Fabian socialist JA Hobson’s Imperialism: A Study (1902 [2005], Cosimo Classics, New York) is seminal. For Hobson, a “new imperialism” had emerged in the last quarter of the nineteenth century as a national policy with a distinctively “economic taproot” (1902 [2005], p. 89). He sketched the outlines of the new imperialism in an imagined justification espoused by the “Imperialists” (1902 [2005], pp. 81-3):

We must have markets for our growing manufactures, we must have new outlets for the investment of our surplus capital … a necessity of life to a nation with our great and growing powers of production. An ever larger share of our population is devoted to the manufactures and commerce of towns, and is thus dependent for life and work upon food and raw materials from foreign lands. In order to buy and pay for these things we must sell our goods abroad … Far larger and more important is the pressure of capital for external fields of investment … Of the fact of this pressure of capital there can be no question. Large savings are made which cannot find any profitable investment in this country; they must find employment elsewhere … [I]f we abandoned [the policy of imperial expansion] we must be content to leave the development of the world to other nations, who will everywhere cut into our trade, and even impair our means of securing the food and raw materials we require to support our population. Imperialism is thus seen to be, not a choice, but a necessity.

Hobson criticised the outlook of the “Imperialists” on economic and social grounds. His argument aimed to add economic sophistication to this criticism. On the one hand, he emphasised and linked the roles of effective demand and the unequal distribution of wealth and income in creating chronic overproduction due to underconsumption. On the other hand, he highlighted the concentration of capital into trusts and combines and linked this with the tendency to limit domestic investment and accentuate overproduction. Already, under a more competitive capitalism, productive capacity had exceeded consumption demand, but concentration introduced a new dynamic (1902 [2005], pp. 85-8):

… in some cases trusts take most of their profits by raising prices, in other cases by reducing the costs of production through employing only the best mills and stopping the waste of competition. For the present argument it matters not which course is taken; the point is that this concentration of industry in ‘trusts,’ ‘combines,’ etc., at once limits the quantity of capital which can be effectively employed and increases the share of profits out of which fresh savings and fresh capital will spring … New inventions and other economies of production or distribution within the trade may absorb some of the new capital, but there are rigid limits to this absorption … The same needs [as in the US] exist in European countries, and, as is admitted, drive Governments along the same path. Overproduction in the sense of an excessive manufacturing plant, and surplus capital which cannot find sound investments within the country, force Great Britain, Germany, Holland, France to place larger and larger portions of their economic resources outside the area of their present political domain, and then stimulate a policy of political expansion so as to take in the new areas. The economic sources of this movement are laid bare by periodic trade-depressions due to an inability of producers to find adequate and profitable markets for what they can produce.

It is hard to think of anything in the twentieth century literature on monopoly and imperialism that had not already been foreshadowed by Hobson. Too often treated, in Marxist circles at least, as a mere footnote to Lenin, Hobson’s Imperialism deserves to be treated, as Lenin noted in the first paragraph of his 1917 Preface to his own Imperialism, “with all the care that, in my opinion, that work deserves”. The long quotation to follow should give readers a better sense of Hobson’s work and why it was influential, especially in promoting underconsumptionist thinking (1902 [2005], pp. 89-91, emphasis added):

The process we may be told is inevitable, and so it seems upon a superficial inspection. Everywhere appear excessive powers of production, excessive capital in search of investment. It is admitted by all business men that the growth of the powers of production in their country exceeds the growth in consumption, that more goods can be produced than can be sold at a profit, and that more capital exists than can find remunerative investment.

It is this economic condition of affairs that forms the taproot of Imperialism. If the consuming public in this country raised its standard of consumption to keep pace with every rise of productive powers, there could be no excess of goods or capital clamorous to use Imperialism in order to find markets: foreign trade would indeed exist, but there would be no difficulty in exchanging a small surplus of our manufactures for the food and raw material we annually absorbed, and all the savings that we made could find employment, if we chose, in home industries.

There is nothing inherently irrational in such a supposition. Whatever is, or can be, produced, can be consumed, for a claim upon it, as rent, profit, or wages, forms part of the real income of some member of the community, and he can consume it, or else exchange it for some other consumable with someone else who will consume it. With everything that is produced a consuming power is born. If then there are goods which cannot get consumed, or which cannot even get produced because it is evident they cannot get consumed, and if there is a quantity of capital and labour which cannot get full employment because its products cannot get consumed, the only possible explanation of this paradox is the refusal of owners of consuming power to apply that power in effective demand for commodities.

It is, of course, possible that an excess of producing power might exist in particular industries by misdirection, being engaged in certain manufactures, whereas it ought to have been engaged in agriculture or some other use. But no one can seriously contend that such misdirection explains the recurrent gluts and consequent depressions of modern industry, or that, when overproduction is manifest in the leading manufactures, ample avenues are open for the surplus capital and labour in other industries. The general character of the excess of producing power is proved by the existence at such times of large bank stocks of idle money seeking any sort of profitable investment and finding none. The root questions underlying the phenomena are clearly these: “Why is it that consumption fails to keep pace automatically in a community with power of production?” “Why does underconsumption or over-saving occur?” For it is evident that the consuming power, which, if exercised, would keep tense the reins of production, is in part withheld, or in other words is “saved” and stored up for investment. All saving for investment does not imply slackness of production; quite the contrary. Saving is economically justified, from the social standpoint, when the capital in which it takes material shape finds full employment in helping to produce commodities which, when produced, will be consumed. It is saving in excess of this amount that causes mischief, taking shape in surplus capital which is not needed to assist current consumption, and which either lies idle, or tries to oust existing capital from its employment, or else seeks speculative use abroad under the protection of the Government.

This “process we may be told is inevitable”, but Hobson set out the broad lines of an alternative (1902 [2005], pp. 94-5). Arguing that it “is not inherent in the nature of things that we should spend our natural resources on militarism, war, and risky, unscrupulous diplomacy, in order to find markets for our goods and surplus capital” he proposed:

An intelligent progressive community, based upon substantial equality of economic and educational opportunities, will raise its standard of consumption to correspond with every increased power of production, and can find full employment for an unlimited quantity of capital and labour within the limits of the country which it occupies. Where the distribution of incomes is such as to enable all classes of the nation to convert their felt wants into an effective demand for commodities, there can be no overproduction, no underemployment of capital and labour, and no necessity to fight for foreign markets. The most convincing condemnation of the current economy is conveyed in the difficulty which producers everywhere experience in finding consumers for their products: a fact attested by the prodigious growth of classes of agents and middlemen, the multiplication of every sort of advertising, and the general increase of the distributive classes. Under a sound economy the pressure would be reversed: the growing wants of progressive societies would be a constant stimulus to the inventive and operative energies of producers, and would form a constant strain upon the powers of production.

How an “intelligent and progressive community, based on substantial equality of economic and educational opportunities”, should not shudder at the racism evident throughout Hobson’s work is another question entirely. Though Hobson’s Imperialism is a necessary reading, it is a painful one.

- 1

At https://monthlyreview.org/2024/11/01/the-new-denial-of-imperialism-on-the-left/ (updated 3 November 2024).

- 2

See https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1916/imp-hsc/index.htm for access to Imperialism and additional references to the work of the Archive. Any errors in compiling the excerpts are mine alone. Unfortunately, the MIA version does not have page numbers.

- 3

See Marx’s Introduction to the Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy (Rough Draft) (1857-8 [1973], Penguin/New Left Review, London, pp. 99-101).

- 4

I suspect that Ernest Mandel is a principal target. In Late Capitalism (1972 [1975], trans. Joris de Bres, New Left Books, London, pp. 594-5), Mandel defines “Monopoly capitalism (Imperialism)” as “that phase in the development of the capitalist mode of production in which a qualitative increase in the concentration and centralization of capital leads to the elimination of price competition from a series of key branches of industry … A trend to regulate (i.e., limit) investment and production in monopolized sectors henceforth prevails, in spite of the existence of monopolistic surplus-profits [that is “specific forms of surplus-profit originating from obstacles to entry into special branches of production”, the general forms of which are “profits over and above the socially average rate of profit”, pp. 595, 597], so that over-accumulation [that is “a state in which there is a significant mass of excess capital in the economy, which cannot be invested at the average rate of profit normally expected by owners of capital”, p. 595] leads to a frantic search for new fields of capital investment and hence to a growth of capital exports.”

- 5

See, however, my “Surplus profits, surplus capital, capital exports and imperialism?” (2025, forthcoming), in which I criticise inter alia the argument expressed by Ernest Mandel in the previous footnote. A useful short contribution is Alice H. Amsden’s entry, Imperialism, in The New Palgrave: Marxian Economics (1987, pp. 205-17; from Eatwell, J., M. Milgate and P. Newman eds. 1987, The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, Macmillan, London).

- 6

The net international investment position (a stock measure at year end) shows the gap between overseas assets owned by resident entities and domestic assets owned by non-resident entities (liabilities). Net lending (a flow measure over the period of a year) shows net purchases less sales of overseas assets by resident entities against the reverse domestically by non-resident entities. In non-technical terms, it serves to represent “capital exports” less “capital imports”. Net annual capital exports — that is, capital exports (+) less capital imports (-) — and net revaluations of international assets and liabilities account for changes in the net international investment position, namely the magnitude attached to creditor or debtor status. All data are in current US dollars, which means that exchange rates, and the various determinants of them, influence the absolute magnitudes. However, exchange rates do not alter the signs. A positive (+) is still a positive, and a negative (-) is still a negative.