Who’s causing the environmental crisis: 7 billion or the 1%?

October 26, 2011 – Grist via Climate and Capitalism, posted at Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal with permission – Ironically, while populationist groups focus attention on the 7 billion, protesters in the worldwide Occupy movement have identified the real source of environmental destruction: not the 7 billion, but the 1%

This article, published today on the environmental website Grist, has provoked a vigorous discussion there. Many of the comments defend variations of the “consumer sovereignty” argument, that corporations only destroy the environment in order to provide the products and services consumers demand. We encourage readers to join that conversation.

* * *

By Ian Angus and Simon Butler

The United Nations says that the world’s population will reach 7 billion people this month.

The approach of that milestone has produced a wave of articles and opinion pieces blaming the world’s environmental crises on overpopulation. In New York’s Times Square, a huge and expensive video declares that “human overpopulation is driving species extinct”. In London’s busiest Underground stations, electronic poster boards warn that 7 billion is ecologically unsustainable.

In 1968, Paul Ehrlich’s bestseller The Population Bomb declared that as a result of overpopulation, “the battle to feed humanity is over” and the 1970s would be a time of global famines and ever-rising death rates. His predictions were all wrong, but four decades later his successors still use Ehrlich’s phrase — too many people! — to explain environmental problems.

But most of the 7 billion are not endangering the Earth. The majority of the world’s people don’t destroy forests, don’t wipe out endangered species, don’t pollute rivers and oceans, and emit essentially no greenhouse gases.

Even in the rich countries of the global North, most environmental destruction is caused not by individuals or households, but by mines, factories and power plants run by corporations that care more about profit than about humanity’s survival.

No reduction in US population would have stopped BP from poisoning the Gulf of Mexico last year. Lower birthrates won’t shut down Canada’s tar sands, which Bill McKibben has justly called one of the most staggering crimes the world has ever seen.

Universal access to birth control should be a fundamental human right — but it would not have prevented Shell’s massive destruction of ecosystems in the Niger River delta, or the immeasurable damage that Chevron has caused to rainforests in Ecuador.

Ironically, while populationist groups focus attention on the 7 billion, protesters in the worldwide Occupy movement have identified the real source of environmental destruction: not the 7 billion, but the 1%, the handful of millionaires and billionaires who own more, consume more, control more and destroy more than all the rest of us put together.

In the United States, the richest 1% own a majority of all stocks and corporate equity, giving them absolute control of the corporations that are directly responsible for most environmental destruction.

A recent report prepared by the British consulting firm Trucost for the United Nations found that just 3000 corporations cause $2.15 trillion in environmental damage every year. Outrageous as that figure is — only six countries have a GDP greater than $2.15 trillion — it substantially understates the damage, because it excludes costs that would result from “potential high impact events such as fishery or ecosystem collapse”, and “external costs caused by product use and disposal, as well as companies’ use of other natural resources and release of further pollutants through their operations and suppliers”.

So in the case of oil companies, the figure covers “normal operations” but not deaths and destruction caused by global warming, not damage caused by worldwide use of its products and not the multi-billions of dollars in costs to clean up oil spills. The real damage those companies alone do is much greater than $2.15 trillion, every single year.

The 1% also control the governments that supposedly regulate those destructive corporations. The millionaires include 46 per cent of members of the US House of Representatives, 54 out of 100 senators and every president since Eisenhower.

Through the government, the 1% control the US military, the largest user of petroleum in the world, and thus one of the largest emitters of greenhouse gases. Military operations produce more hazardous waste than the five largest chemical companies combined. More than 10 per cent of all Superfund hazardous waste sites in the United States are on military bases.

Those who believe that slowing population growth will stop or slow environmental destruction are ignoring these real and immediate threats to life on our planet. Corporations and armies aren’t polluting the world and destroying ecosystems because there are too many people, but because it is profitable to do so.

If the birthrate in Iraq or Afghanistan falls to zero, the US military will not use one less gallon of oil.

If every African country adopts a one-child policy, energy companies in the US, China and elsewhere will continue burning coal, bringing us ever closer to climate catastrophe.

Critics of the too many people argument are often accused of believing that there are no limits to growth. In our case, that simply isn’t true. What we do say is that in an ecologically rational and socially just world, where large families aren’t an economic necessity for hundreds of millions of people, population will stabilise. In Betsy Hartmann’s words, “The best population policy is to concentrate on improving human welfare in all its many facets. Take care of the population and population growth will go down.”

The world’s multiple environmental crises demand rapid and decisive action, but we can’t act effectively unless we understand why they are happening. If we misdiagnose the illness, at best we will waste precious time on ineffective cures; at worst, we will make the crises worse.

The too many people argument directs the attention and efforts of sincere activists to programs that will not have any substantial effect. At the same time, it weakens efforts to build an effective global movement against ecological destruction: It divides our forces, by blaming the principal victims of the crisis for problems they did not cause.

Above all, it ignores the massively destructive role of an irrational economic and social system that has gross waste and devastation built into its DNA. The capitalist system and the power of the 1%, not population size, are the root causes of today’s ecological crisis.

As pioneering ecologist Barry Commoner once said, “Pollution begins not in the family bedroom, but in the corporate boardroom.”

[Ian Angus and Simon Butler are the coauthors of Too Many People? Population, Immigration, and the Environmental Crisis.]

Population, consumer sovereignty, and the importance of class

By Ian Angus

October 28, 2011 – Climate and Capitalism – This week, the environmental website site Grist published an article by Simon Butler and me, Is the environmental crisis caused by the 7 billion or the 1%? This was a departure for Grist, which frequently carries articles warning of an impending overpopulation apocalypse. Kudos to editor Lysa Hymas for commissioning and publishing an article I’m sure she doesn’t agree with, in order to promote discussion of this important issue.

The article was posted on October 26, and by October 28, 820 people had “liked” it on Facebook, making it one of the three most-liked articles in Grist‘s population section this year.

But judging by the comments it received, some readers are less than keen about any discussion that focuses on issues of class, power and inequality. One wrote:

What a piece of leftist drivel. I don’t need to say this because most of the other commentors already have, but this crap is another low point for Grist.

The most frequent criticism from Grist commenters accuses us of failing to understand that consumer desires drive the economy, that corporations are just responding to our demands, expressed through the market. The system isn’t at fault, “we” are.

Some examples:

“Billionaires aren’t mining and pillaging for their own enjoyment – almost all of us in developed nations use those resources every day.”

“The 1% may own the companies and wealth, but that wealth comes from selling us all stuff, and it is hypocritical to say that all of us have not invested something in the global economic system. ”

“Less consumers equals less demand equals less consumption equals less sprawl equals less congestion equals less garbage equals less need for fossil fuels. Grist is on the wrong side of this issue.”

“But BP could not have polluted the Gulf Coast if there was no demand for petroleum. The demands of those 7 billion are driving corporations to fulfill the demands of all the humans inhabiting this planet. After all, if we were at say 3 billion now BP would not have had to drill in the Gulf in the first place.”

I responded to these comments with a brief summary of arguments that Simon and I make in Chapter 12 of Too Many People?

That view, known to academic economists as “consumer sovereignty,” suffers from at least four fatal weaknesses.

First, it ignores the immense market power of the wealthiest consumers. In the U.S., the richest one percent have greater wealth than the bottom 90 percent combined. The poorest 50% collectively own just 2.5% of all U.S. wealth. Analysts at Citibank have used the term ‘plutonomy” to describe the economies of the U.S., Canada, U.K., Australia, and others, which are dominated “rich consumers, few in number, but disproportionate in the gigantic slice of income and consumption they take.”

Second, it ignores the fact that markets aren’t just unbalanced in favor of rich buyers, they are consciously manipulated by rich sellers. The 1% aren’t just richer, they have the power to engage in what John Kenneth Galbraith called “management of demand” – far from just responding to consumer demand, corporations actively create demand for the products they find most profitable to sell.

Third, it ignores the fact the range of choices available to buyers is determined not by what is environmentally friendly, but by what can be sold profitably. As a result, we get microchoices such as Ford vs Hyundai — but not real choices such as automobiles vs reliable and affordable public transit.

Fourth, it ignores the fact that buyers have little or no influence over how products are made or produced. BPs decision to ignore safe drilling practices in the Gulf, Shell’s decision to dump oil in the Niger –those decisions were made not by consumers but by corporate executives, to maximize the profits demanded by their shareholders. And remember – 1% of the population owns a majority of stocks.

In short, the 1%, not the 7 Billion, control what is sold and how it is produced.

The underlying problem with the discussion, I think, is that many Grist readers – certainly the ones that are unhappy with what we wrote – are blind to class. They know that the 1% do more environmental damage than the rest of us, but view it as just a matter of degree, not as a fundamental class divide.

In fact, to echo F. Scott Fitzgerald, the very rich are different from you and me. As we wrote in Too Many People? they don’t just have more money:

At some point near the top of the income ladder, quantitative increases in income lead to qualitative changes in social power, exercised not through consumption but through ownership and control of profit-making institutions.

The Grist commenter who wrote that we all damage the environment, “the rich are just more destructive”, seems to be unaware of just how vast the gap exists between the very wealthy and the rest of us.

Perhaps this will clarify matters for greens who don’t trust what two leftists have to say. Last week, the decidedly non-socialist investment bank Credit Suisse issued its annual Global Wealth Report. Its main conclusion was reported by the decidedly non-socialist Wall Street Journal.

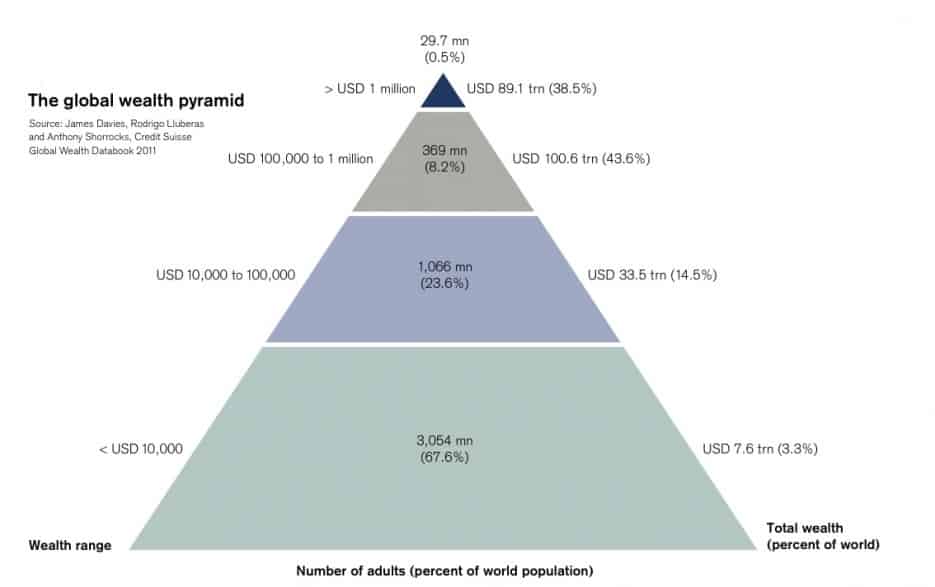

Here’s another stat that the Occupy Wall Streeters can hoist on their placards: The world’s millionaires and billionaires now control 38.5% of the world’s wealth. … the 29.7 million people in the world with household net worths of $1 million (representing less than 1% of the world’s population) control about $89 trillion of the world’s wealth.

This Credit Suisse graphic gives some idea of how unequally global wealth is distributed.

Economics professor David Ruccio comments in the Real-World Economics Review blog:

the figures for mid-2011 indicate that 29.7 million adults, about 1/2 of one percent of the world’s population, own more than one third of global household wealth. Of this group, they estimate that 85,000 individuals are worth more than $50 million, 29,000 are worth more than $100 million, and 2,700 have assets above $500 million.

Compare this to the bottom of the pyramid: 3.054 billion people, 67.6 percent of the world’s population, with assets of less than $10,000, who own a mere 3.3 percent of the world’s wealth.

Add another billion people with assets between $10,000 and $100,000 and we have 91.2 percent of the world’s population that owns something on the order of 17.8 percent of total world wealth.

He could have added that most of the wealth held by the bottom 90% consists of family homes, while richest 1% own most corporate shares. The rich aren’t just richer — they own wealth that gives them control of our economic system, and they profit from environmental destruction.

Reducing human numbers might, over many decades, make a small difference to the global environment. Eliminating the wealth and power of the 1% is the only way to completely turn things around.

7 billion people. Should we panic?

On 31 October, according to the UN, world population tops seven billion.

It’s only 13 years ago that we hit six billion. So is population exploding? It certainly sounds like it, judging by many media reports.

But take a look at these graphics and you may see another picture emerging. Let’s start with the projections:

The top line assumes a high total fertility rate, or number of children a woman will have on average during her lifetime. This takes us to around 11 billion people by 2050.

The middle one (which is most commonly used) assumes a medium or ‘replacement’ fertility rate and takes us up to around nine billion.

The lowest assumes a below replacement fertility rate and takes us to around eight billion.

So, a lot depends on the fertility rate and its impact on family size:

In around 76 countries in the world, the current population is not even replacing itself. But is some low income countries, especially those in sub-Saharan Africa, the fertility rate has remained high, with women having around five children on average.

Let’s look at what happens to those three projections beyond 2050:

In a low fertility scenario world population peaks by 2050 and starts to decline. By 2100 we are back where we were 1998, with six billion people. This is what some population experts, including the UNFPA’s Ralph Hakkert, think will happen.

In a medium fertility scenario, where people carry on replacing themselves, the rate of population growth slows down until we gradually reach 10 billion by 2100.

In a high fertility world we hit 16 billion by 2100.

As we have seen over the past 50 years, the global trend is quite definitely towards smaller families. Once that trend begins, with people having fewer children or none at all, it is hard or even impossible to reverse – as policy in makers have found in countries with shrinking populations like Japan or Korea or parts of Europe.

We know that one of the strongest factors in determining family size is women’s education and empowerment.

Just look at what happens to fertility rates when women become more literate.

Some people who are concerned about global warming are saying that the priority has to be bringing down fertility rates in the countries where they are high. Currently 18 per of the world’s population lives in such countries low-income countries.

But the areas where population is growing fastest are those that emit least CO2 while countries where population is growing slowly or shrinking emit the most.

Look at this:

Cutting fertility in low income countries is unlikely to make much impact on global warming at all.

So should the gas-guzzling, high-consuming, high-income citizens of the rich world abstain from having babies, then?

They might, but still this does not deliver the cuts in CO2 we need – 80 per cent by 2050. Researchers at the National Centre for Atmospheric Research at Boulder Colorado have found that a reduction of around one billion in world population would deliver a cut of only around 15 per cent.

So, what do we need to do? Get off fossil fuels and switch to renewable energy. Stop wasting so much energy and food (up to half the world’s food gets wasted). Ban the type of financial speculation on food that is driving up food prices. Foster sustainable farming methods.

But above all remember that population is about people – not just numbers. More important than how many we are, is how we use and how we share the earth’s resources.

Contents list:

1 Are too many people being born?

2 A brief history of population

3 Being alive, staying alive – and growing old

4 A woman’s body

5 For richer, for poorer

6 On the move

7 Population and climate change

8 How can we feed nine billion

9 Wild things

10 Conclusion

Order now from the New Internationalist shop.