Applying/misapplying Gramsci’s passive revolution to Latin America

First published at Monthly Review.

The second wave of progressive Latin American governments that began with the election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador in Mexico in 2018 does not have the aura of excitement surrounding the first, dating back to Hugo Chávez in 1998. It is not only characterized by pragmatism, but lacks the slogans and banners of radical change associated with Chávez and Evo Morales. As stated by former Bolivian vice president Álvaro García Linera in the face of challenges from an aggressive right, the second-wave left “turned up to the fight in an already exhausted state.”1

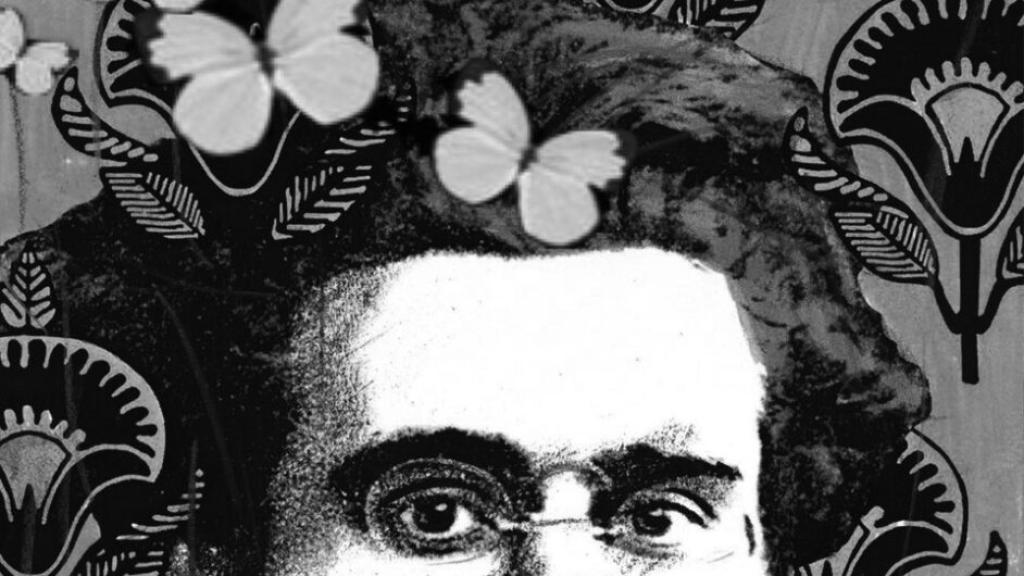

It is no small wonder the criticisms formulated by leftist detractors of these progressive governments, known as the Pink Tide, have become increasingly severe. Over recent years, these critics have analyzed Pink Tide governments through the lens of Antonio Gramsci’s concept of “passive revolution,” as have leftist analysts of other governments that began as progressive and then moved in a rightist direction, such as that of post-apartheid South Africa and those associated with African socialism and Pan-Arabism. In broad strokes, passive revolutions occur in revolutionary situations, often in the context of uneven development, in which a strong state grants concessions to the popular sectors, but ends up taming them and derailing the revolutionary process while, to varying degrees, modifying capitalist relations.

The critique of Pink Tide governments is strengthened by the setbacks that followed the electoral triumphs of López Obrador, Alberto Fernández in Argentina (2019), Luis Arce in Bolivia (2020), Gabriel Boric in Chile (2021), and Pedro Castillo in Peru (2021). Such setbacks include the overthrow and imprisonment of Castillo in 2022, the virtual schism in Bolivia’s ruling Movimiento al Socialismo — largely due to the competing presidential aspirations of Arce and Morales, and the election of Trump-admirer Javier Milei in Argentina. The most recent problem area is the Venezuelan presidential elections of July 28, the results of which have not been adequately clarified, and the subsequent two days of violence in popular neighborhoods, which demonstrated that the Chavistas are not the dominant force that they were in previous rounds of disturbances. I maintain that in spite of these discouraging developments, the Pink Tide is far from being a lost cause, and that Pink Tide movements continue to be anti-imperialist strongholds in a world in which the far right has made ongoing inroads.

Some of the harshest critics of the Pink Tide’s second wave were zealous admirers of the first, particularly in the case of Chávez, in contrast to Nicolás Maduro.2 This is largely because the initial momentum of the second wave was so short-lived, especially compared to that of the first, which was driven by a series of dramatic breakthroughs, including Chávez’s return to power after the coup staged on April 11, 2002; his proclamation that he was a socialist at the World Social Forum in January 2005; the definitive defeat of the U.S.-sponsored Free Trade Area of the Americas proposal at the Summit of the Americas in 2005; and the partial nationalizations of hydrocarbon industries by Chávez, Morales, and Argentine president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.

Nevertheless, developments in the twenty-first century lend themselves to the point of view that current Pink Tide governments, with all their limitations — including concessions to private capital — play a progressive role. Two compelling facts stand out. First, Pink Tide governments have directly challenged U.S. interventionism, which has become more blatant in Latin America in the second wave than at the outset of the first wave. Second, due to the extreme political polarization in Latin America, as elsewhere in the world, the leading alternatives to the Pink Tide are extreme rightist, if not semifascist, movements aligned with Washington.

That said, the Pink Tide today hardly embodies the revolutionary spirit that Chávez unleashed two decades earlier. A distinction needs to be made between critical support for the Pink Tide and the passive revolution analysis that gets translated into frontal opposition to those governments. The critical support position views Pink Tide governments as basically progressive, but, at the same time, contested territory in which the middle classes, capitalists, and popular sectors often weigh in heavily. That position takes into account the fact that the political adversary of those governments consists of reactionary domestic forces, including the dominant fractions of the local capitalist class, backed by U.S. imperialism. The position of critical support converges with that of social movements, which, for the most part, have supported the Pink Tide in moments of political crisis, without renouncing their autonomy. In contrast, the framework of passive revolution lends itself to the view that the end result of the Pink Tide phenomenon, which is torn with contradictions, is the restoration of the old order and, to put it bluntly, the selling out of those who lead the process.

The passive revolution concept put to the test

In different Pink Tide countries, renowned scholars on the left have analyzed the governments of their respective countries in the framework of the theory of passive revolution. Once having adopted this framework, they all reach the conclusion that Pink Tide leaders have turned their backs on the banners that catapulted them to power. Three major examples include Carlos Nelson Coutinho, who has been described as “Brazil’s leading Gramscian,” Luis Tapia in Bolivia, and Maristella Svampa of Argentina.3

Some passive revolution writers deny that Pink Tide governments have any redeeming qualities. For them, the Pink Tide’s passive revolution constitutes “a step backward,” or a revolution betrayed.4 Some of them have accused those who defend the Pink Tide of “capitulation” or, even worse, of being commissioned by those governments.5 The well-known Uruguayan writer and activist Raúl Zibechi, who also embraces Gramsci’s writing, quotes a resident of a Rio de Janeiro favela as saying the main problem is “the complementarity between the center-left governments that destroy the movements and the right-wing ones that destroy the social façade of the state — a perfect combination.”6

Other passive revolution writers present a more nuanced interpretation of the concept, but also end up denying the basically progressive nature of Pink Tide governments. Massimo Modonesi, the scholar who has done the most to apply the framework of passive revolution to twenty-first-century Latin America, points out that by the transformismo of passive revolution, Gramsci meant “doses of renovation and conservation” that play out as a dialectical relationship. The end product is not a return to a previous state, since “progressive restoration is not a total restoration.” Alluding to the Pink Tide, Modonesi warns against “ignoring the importance of the current transformations [or] disqualifying a group of governments — some more than others — that are encouraging processes that are to a significant extent anti-neoliberal and anti-imperialist.”7 Another Marxist scholar who has written extensively on passive revolution and Latin America, Adam David Morton, observes that Gramsci’s intention was “open ended,” and that fatalism needs to be avoided at all costs.8

In their analyses of the Pink Tide, however, none of these writers come close to striking a balance between the “progressive” and “restoration” components of passive revolution. They recognize what only the most aggressive adversaries of the Pink Tide deny: namely, the accomplishments of progressive Latin American governments in the area of social programs. But, according to them, this positive side is more than offset by a negative side. Modonesi writes that the social measures “not only do not guarantee the proper and durable means for the poor to achieve their welfare but … they operate … as powerful devices for cronyism and the construction of political loyalties.” He adds that the measures are, in effect, a “top-down construction of passivity,” which is part of a process “overseen by the “dominant classes that…incorporates certain demands of the subalterns in order to demobilize their movement.”9 Another writer on the left who avoids simplistic notions regarding passive revolution, Jeffery Webber, concludes an article on Morales’s presidency: “In the revolutionary/restorative dialectic of passive revolution, I have demonstrated on multiple levels the determining tendency of restoration, of preservation over transformation.”10

Although in theory the outcome of passive revolutions is not predetermined, in the case of the Pink Tide, Modonesi, Webber, and other passive revolution theorists view it as largely a foregone conclusion. Modonesi points to the beginning of the second decade of the century as a turning point, after which “the passive element … became characteristic, distinctive, decisive and common.” He adds, “in the context of these passive revolutions … groups or entire sectors of popular movements were co-opted and absorbed by conservative forces, alliances, and projects.”11 The use of the terms “project” (as in “project of demobilization,” “project of restoration,” and “Rafael Correa’s project”) and “the new order” by passive revolution writers to describe limited or meager concessions by Pink Tide governments to the popular sectors is somewhat misleading.12 In many cases, these concessions should be seen not as an “elite-engineered” process, but part of a leftist strategy to buy time in situations of crisis, and thus need to be contextualized, rather than considered a finished product based on a preconceived project.13 The magnitude of the imperialist threat to Pink Tide governments should enter into the equation but many passive revolution writers on Latin America attach little importance to it, if any at all.14 According to their line of reasoning, V. I. Lenin’s New Economic Policy could have been classified at the time as a passive revolution, and the Communist no-strike policy during the Second World War could have been viewed in the same vein.

The prevailing situation, in which Pink Tide governments have reached power, is dynamic. The state in those countries is clearly more akin to a “battleground” of competing social forces, as theorized by Nicos Poulantzas, than to a vertical structure with economic and political elites securely sitting at the top. Characterizing the Pink Tide governments as the demobilizers within the context of a passive revolution does not tell the whole story.

In an article prior to Morales’s overthrow in 2019, Webber wrote: “There is a molecular change in the balance of forces under passive revolution, gradually draining the capacities for self-organization and self-activity from below through co-optation, guaranteeing passivity to the new order.”15 However, subsequent events proved that passive revolution was not an ideal framework to understand Bolivian political developments. The social movements that had clashed with the Morales government over specific issues united first with his Movimiento al Socialismo party to force the right-wing government to hold elections, and then ended up supporting the socialist party’s presidential candidate, Arce. The endorsement of Arce by the intransigent Felipe Quispe, Morales’s arch social movement rival, symbolized the convergence of social movements and the Pink Tide. This scenario is a far cry from the clear-cut divide between a Pink Tide state that is increasingly subservient to bourgeois interests, versus autonomous, if not antistatist, movements from below, as envisioned by passive revolution writers.16

Events in Brazil also call into question the applicability of the passive revolution concept to the demobilization of social movements under Pink Tide governments. William Robinson, for instance, defines passive revolutions as situations in which “dominant groups undertake reform from above that defuses mobilization from below for more far-reaching transformation.”17 Robinson and other Pink Tide critics on the left point to the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST) as a paradigmatic example of an autonomous social movement that has staunchly criticized Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s former government in the area of land distribution. Some of these critics, including passive revolution scholar Coutinho, favored a complete break with Lula and his Workers’ Party and praised the Socialism and Liberty Party, the leaders of which were expelled from the Workers’ Party in 2004 for being too far to the left.18 Nevertheless, the passive revolution paradigm, which highlights co-optation and demobilization cannot explain why the MST, in the context of the extreme polarization driven by the government of Jair Bolsonaro, forcefully pushed for Lula to be the left’s candidate in the 2022 presidential elections. In doing so, the MST vetoed the proposal for a more centrist anti-Bolsonaro alliance. The Socialism and Liberty Party supported the same position.

The co-optation of social movement activists, which is the cornerstone of the passive revolution theory applied to Latin America, is more complex than what passive revolution theorists claim. In Argentina, for instance, many members of the generation of youth protesters who forced neoliberal president Fernando de la Rua to resign in 2001 joined social movements such as La Cámpora, created by Néstor Kirchner (and headed by his son), and the Movimiento Evita created by his successor, Cristina Kirchner de Fernández. Pink Tide detractors both on the left and the right painted the pro-Kirchner social groups as lackies of the president. But these activists saw themselves in a different light. Rather than “bureaucrats,” those who entered the state sphere considered themselves to be “militants” in a public space “under dispute.” In fact, they represented a leftist faction within Kirchnerism that served to counter the more conservative currents within the Peronist movement.19

García Linera, whom Webber criticizes for advocating a strategy of stages based on relative stability rather than ongoing transformation, characterizes the relations between Pink Tide governments and social movements as one of “creative tensions.”20 The term, in some cases, exaggerates the degree of creativity and underestimates the degree of conflict. Elsewhere I have pointed to cases of sectarianism by Pink Tide governments toward leftists outside the governing party and toward social movements, which, as Poulantzas posits, play a fundamental role in revolutionary transformation — especially when it is by peaceful means.21

Nevertheless, a distinction needs to be drawn between social movements, like the MST, that are critically supportive of progressive governments and intransigent movements that continuously clash with Pink Tide governments. In line with their praise for the latter, passive revolution writers and other Pink Tide detractors on the left highlight social movement leaders who have run for president against Pink Tide candidates.22 Pinpointing these leaders to shed light on the resistance to the process of passive revolution may not be the best choice. Among them are Quispe of Bolivia in 2005, Luis Macas of Ecuador in 2006, and Alberto Acosta of Ecuador in 2013, each of whom received 2 to 3 percent of the vote. Yaku Pérez, the Ecuadorian anti-Pink Tide Indigenous leader, appeared to break this pattern in the first round of the presidential elections in 2021, garnering 19 percent of the vote, but he then secured the election of conservative banker Guillermo Lasso in the second round by refusing to endorse the progressive Pink Tide candidate Andrés Arauz. Pérez went on to run in the 2023 electoral contests and pulled in a mere 4 percent, as opposed to the 48 percent that the Pink Tide presidential candidate received in the second round.

Passive revolution writers also overstate their case when they allege that Pink Tide governments have done more to further the interests of global capitalism than conservatives and that this feat has been recognized by the apologists of the established order. Webber writes: “With hindsight … it seems Morales has been a better night watchman over private property and financial affairs than the Right could have hoped for.” He also quotes the Financial Times as saying that Morales’s rhetoric of “mouthing off at capitalists and imperialists … provided political cover for closer alliances with the country’s private sector.”23 As a result, in the words of Robinson, many “Pink Tide states were able to push forward a new wave of capitalist globalization with greater credibility than their orthodox and politically bankrupt neoliberal predecessors.”24 Webber, Modonesi, and other passive revolution writers attribute “the eventual close of the progressive period” beginning in 2015 to the Pink Tide’s retrograde policies.25

It is hard to believe, however, that imperialism views the Pink Tide with any degree of approval. If it does, how can one explain the devastating sanctions imposed on Venezuela and Nicaragua and the well-documented role of the U.S. Justice Department in the jailing of Lula? Of course, that is just the beginning of a nearly endless list of Washington initiatives, including coups and attempted coups, aimed at undermining the Pink Tide.

Modonesi and Morton flatly reject the claim that the concept of passive revolution, which has been associated with countries as dissimilar as Communist China and Argentina under Juan Perón, has been overextended. In response to the observation of Trotskyist activist and scholar Alex Callinicos that passive revolution is an example of “concept stretching” as it has “come to take on an infinity of meanings,” Morton asserts that “passive revolution is alive and kicking.” He characterizes the position defended by Callinicos as “deeply anti-historicist.”26

Nevertheless, one fundamental difference between the historical cases analyzed by Gramsci and the Pink Tide phenomena calls into question the applicability of passive revolution to twenty-first-century Latin America. Gramsci derived his concept of passive revolution from his interpretation of the Risorgimento (Italian unification) in the latter half of the nineteenth century and Italian fascism in the 1920s. Karl Marx developed the similar concept of Bonapartism, which is sometimes invoked by passive revolution writers and other leftist critics of the Pink Tide on the basis of France’s experiences under Napoleon I and Napoleon III.27 The four cases occurred in the context of combative social and political movements in revolutionary environments. But the dominant leaders of all four did not come from solid revolutionary or leftist backgrounds by any rational definition of the term.28 This context cannot be brushed aside, because it had a direct bearing on the outcome of the process. Indeed, Gramsci recognized the importance of the trajectories of passive revolution leaders. He wrote: “A social group can, and indeed must, already exercise ‘leadership’ before winning governmental power (this indeed is one of the principal conditions for the winning of such power).… It seems clear from the policies of the [Resorgimento] Moderates that there can, and indeed must, be hegemonic activity even before the rise to power.”29

The Pink Tide settings tell a different story. In contrast to the four cases analyzed by Marx and Gramsci, most (though not all) of the leading figures in Pink Tide governments were previously immersed, and, in some cases, played major roles in popular struggles, and participated in left-wing social and political movements. Lula, Morales, and Maduro emerged from worker struggles; Gustavo Petro in Colombia and the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front leaders who came to power in El Salvador participated in guerrilla movements; López Obrador, Gabriel Boric (Chile), and Xiomara Castro de Zelaya (Honduras) played leading roles in massive mobilizations against neoliberalism; Chávez, through his brother Adán, was associated with a split-off Communist guerrilla faction that attempted to recruit military officers; and the Fifth Republic Movement, which launched Chávez’s presidential candidacy in 1997–1998, was largely led by leftists, including Maduro. The very fact that the top leaders of these Pink Tide movements prior to reaching power were committed to far-reaching socioeconomic change, if not socialism, points to a far different dynamic and outcome than in the case of the Risorgimento and fascist movements analyzed by Gramsci. Most important, Pink Tide parties were more likely to be subject to internal contradictions and conflicts, and the process was less likely to be linear than in the two Italian cases.

The structure and superstructure of the passive revolution

Passive revolution writers view Pink Tide governments as having succumbed to global capitalism, in the process giving up their relative autonomy vis-à-vis powerful interest groups. The envisioned model as it relates to the Pink Tide is based on an all-pervasive global capitalist structure, as opposed to government policies (the superstructure) that are at best timidly progressive and have been watered down by the co-optation of militant social movement activists, repression, and corruption. Passive revolution writers argue that the structure is wedded to so-called “neo-extractivism,” in which the local economy and the global economy dovetail more than ever before. According to this concept, Latin American governments took advantage of the primary commodities boom (for example, unprocessed raw materials, hydrocarbons, and soybeans) by increasing the export of those products at the expense of the industrial progress that had previously been registered. Webber points out that some of the benefits of extractivism filter down to the popular sectors, but these “relatively petty handouts run on the blood of extraction,” resulting in an increasingly “repressive state (even with a left government in office) on behalf of capital, as the expansion of extraction necessarily accelerates what David Harvey calls accumulation by dispossession.”30 Svampa, who adheres to the passive revolution thesis as applied to Kirchnerism in her native Argentina, calls this strategy the “commodities consensus,” as both leftist and rightist governments converge in prioritizing commodity exports and the windfall revenue derived from them.31

Not only do passive revolution writers belittle the importance of the Pink Tide’s welfare programs, but also its strategy of economic diversification through the cultivation of new economic partners both in the region and worldwide. Some of them conflate Brazil’s economic initiatives abroad with U.S. imperialism. They also view the asymmetry between Pink Tide governments and China as a replica of traditional imperialist relations between metropolises and satellites, a relationship that the governments of the latter uncritically accept. In this context, China is viewed as increasingly becoming just one more major imperialist power. As Robinson puts it, “the emerging centers in this polycentric world are converging around remarkably similar ‘Great Power’ tropes [that are] especially jingoistic.”32

This analytical focus on the structure of global capitalism at the expense of factors related to the superstructure begs for closer examination. The underlying argument of passive revolution writers is that the Pink Tide’s performance needs to be theorized from a Marxist perspective on the basis of class interests. Given the Pink Tide governments’ failure to even attempt to lessen dependence on the export of primary commodities, and given their undeniable ties with certain capitalist groups, then the superstructure in the form of Pink Tide policies must be nothing more than a mere echo of the capitalist structure. Their conclusion is simple and obvious: there is not much progressive about Pink Tide governments.

But facts are facts, and if there are discrepancies between the facts and theory, it is the latter that needs to be revised. Proving that the policies of Pink Tide governments were progressive in fundamental ways would, at the least, poke holes in the theory of passive revolution applied to Latin America and, more seriously, would expose it for being reductionist. In that case, the underlying assumption that the structure of Pink Tide countries consists of a largely undifferentiated bloc taking in both transnational capitalists and the dominant domestic bourgeoisie would be open to question, and it would be necessary to view the state in those countries as a battleground of conflicting social forces (à la Poulantzas), rather than an instrument of the dominant bourgeoisie. In short, the plausibility of the passive revolution theory applied to Latin America hinges on the characterization of Pink Tide policies as serving the interests of capitalism, with nothing much more than crumbs for the popular sectors.

Just how progressive are progressive Latin American governments?

Foreign policy, more than any other realm, clearly defines Pink Tide governments as progressive, without exception. Indeed, the divide between the foreign policy of all Pink Tide governments and that of centrist and rightist ones could not be starker. Take the case of Israel’s 2023 invasion of Gaza and the issue of Palestine. Lula’s falling out with Washington occurred after his recognition of Palestinian statehood in 2010, after which other Pink Tide governments followed suit. After Israel’s recent invasion of Gaza, the Pink Tide governments of Colombia, Brazil, Venezuela, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Chile, and Honduras accused Israel of committing genocide, and most withdrew ambassadors from Tel Aviv (or threatened to do so). Nearly all have harshly criticized the United States for its support of Israel (though Mexico’s position was surprisingly more restrained). In contrast, the centrist and rightist governments of Ecuador, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Argentina (under Milei) supported the Israeli invasion of Gaza; the latter announced its intentions of moving the nation’s embassy to Jerusalem.

Also consider the U.S. sanctions against Cuba and Venezuela. In October 2023, the Pink Tide presidents of Colombia, Honduras, Venezuela, and Mexico were instrumental in passing a resolution at a Latin American summit of twelve nations in Palenque, Mexico, denouncing the sanctions. None of the conservative South American nations attended the meeting. In contrast, at the height of the conservative backlash against the Pink Tide in 2017, the ad hoc “Group of Lima,” consisting of over a dozen Latin American nations, was established in order to push for regime change in Venezuela.

Similarly, the progressive banner of Latin American unity and integration — which for over a century challenged the prevailing hemispheric-wide, U.S.-dominated pan-Americanism — split the continent along ideological lines. Pink Tide governments promoted the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA), the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, and the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR). The most radical, ALBA, which was founded by Chávez and Fidel Castro, lost three key members when Pink Tide governments were overthrown in Honduras, Bolivia, and Ecuador. When the Pink Tide returned to power in Bolivia, it rejoined ALBA, a move that Xiomara Castro is also considering. In contrast, the conservative and rightist governments in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Paraguay, and Peru suspended their membership in UNASUR in 2018. The following year, the anti-Pink Tide president of Ecuador, Lenín Moreno, dislodged the organization from its headquarters in Quito. The vicissitudes of the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR) tell a similar story.

The position of Latin American governments on Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS) follows the same pattern. After assuming the presidency in 2023, Lula prioritized the strategy of opening BRICS to new members with the aim of revitalizing Third Worldism and avoiding a revival of the bipolarity of the first Cold War, with BRICS serving as a front for Russia and China. He also calls for a BRICS currency equivalent to the euro and with “different criteria” for its lending than that of the International Monetary Fund (IMF).33 BRICS status as a cornerstone of Lula’s foreign policy contrasts with Bolsonaro’s lethargy on the international front. It also contrasts with Milei’s decision to cancel Argentina’s membership in BRICS, which had been lobbied for by his predecessor, Pink Tide president Alberto Fernández.

Robinson’s analysis of BRICS, like passive revolution writing on Latin America in general, subsumes progressive initiatives like these into the structure of global capitalism and its imperatives. A case in point is the measures and proposals coming from BRICS to sidestep the dollar for international transactions. Robinson points out that China’s proposal for a world currency issued by the IMF would “help save the global economy from the dangers of continued reliance on the U.S. dollar.” He adds that implementing ideas along these lines, even though they “clash with the G7 … would have the effect of extending and contributing to the stabilization of global capitalism and … further transnationalizing the dominant groups in these countries.”34 Although the argument is plausible, Robinson makes no mention of the fact that the BRICS currency plans will undermine Washington’s nefarious system of international sanctions, which are predicated on the supremacy of the dollar and have wreaked havoc on the economies of Cuba, Venezuela, and many other nations. His statement that the upshot of the currency proposal would be the “stabilization of global capitalism” is thus incomplete in that it ignores, or plays down, the importance of providing breathing space to countries committed to socialism.

Other progressive positions assumed by BRICS are also viewed as mere byproducts of jockeying by globally oriented capitalists of the Global South for a greater voice in world affairs. The way Robinson frames the issue, Pink Tide actions in favor of popular causes appear to be of limited significance because those governments have been incorporated into the web of an unjust global capitalist system. Robinson, for instance, recognizes and approves of the BRICS stand on Palestinian rights and other issues with an eye toward achieving a “more balanced inter-state regime.” But, he adds that the multipolar system “remains part of a brutal, exploitative, global capitalist world in which the BRICS capitalists and states are as much committed to control and repression of the global working class as are their Northern counterparts.”35

In other words, for Robinson, the transnational economic system trumps everything else. He says in order to understand the BRICS phenomenon, it is necessary to go beyond “surface phenomena” involving the tensions and conflict of “inter-state dynamics” in order “to get at the underlying essence of social and class forces in the global political economy.” All this leaves little room for placing pragmatic politics in favor of popular and national interests (for instance, transferring technological skills from the Global North to workers in the South) at the center of analysis. After all, the end result is the BRICS capitalist class’s “greater integration into global capitalism and heightened association with transnational capital,” and making the system of global capitalism more rational.36 Robinson’s framing fails to take into account the rationale behind alliances between the popular sectors and fractions of the bourgeoisie in certain circumstances in countries of the Global South. More specifically, Robinson’s approach leaves little room for giving serious consideration to Maduro’s claim that concessions to private capital are part of a defensive strategy designed to weather the effects of the debilitating sanctions imposed by Washington, not to mention a world in which the right has gained the upper hand. Robinson, his extensive and valuable research into “transnational capital” notwithstanding, fails to empirically demonstrate why these leftist strategies should be relegated to the category of superficial “superstructure” divorced from the structure, as opposed to being placed at center stage along with global capitalism.

It is disturbing that Robinson and other BRICS critics on the left repeatedly accuse those who view that bloc in a positive light (or those who have a favorable view of China) as running the risk of becoming “cheerleaders” for global capitalists of the South.37 That is to say, support for Lula and BRICS gets translated into cheerleading for capitalists. The use of the term “cheerleaders” inadvertently lends itself to a binary outlook (the “you are with us or against us” nonsense) reminiscent of the first Cold War, when the left was accused by the self-styled center-left of siding with the enemy. In those days leftists were, in effect, told you have to criticize forcefully the enemy bloc (the “Communists,” of course) since otherwise you were accused of being a “dupe,” a “fellow traveler,” or worse. Those on the left who praise Brazil under Lula or the rest of the Pink Tide, or China for that matter, should not feel obliged to formulate criticisms of those nations just to demonstrate their credentials as non-“campist” revolutionaries.

Discarding passive revolution — but in favor of what?

In the world that emerges from the passive revolution writing analyzed in this article, autonomous social movements are pitted against global capitalism, with not much in between. The state in Pink Tide countries is so wedded to the so-called transnational capitalist class and to the extractivist model that the end result of its “project” of demobilization and co-optation of reformers and leftists is a forgone conclusion.

I believe this analytical framework is counterproductive in that it blurs important issues that need to be rigorously analyzed and debated on the left. Most important, the progressive politics of Pink Tide governments cannot be played down or relegated to a category of secondary importance. At the root of the issue is the perennial debate among Marxists over structure and superstructure. Is the structure, global capitalism, the principal focus in the analysis of nonsocialist progressive governments like the Pink Tide, as claimed by passive revolution writers on Latin America, determining all else? Or is the relationship between structure and superstructure in these countries more complex (as Louis Althusser argued), with no simple cause-and-effect relationship?

One basic fact overlooked by Pink Tide detractors on the left is the quarter-century duration of the phenomenon, and the large number of countries that it comprises, in the context of relentless resistance backed by imperialist powers. This, in itself, is a historic accomplishment. The sheer number of complex issues surrounding these experiences, with evidently no easy answer, is an even weightier factor, countering the thesis that the Pink Tide is moving in a predictable direction favorable to global capitalism. The following are several of these knotty issues that demonstrate the complexity of the Pink Tide phenomenon, the unpredictability of its final outcome, and the need for a debate on the topic free of conceptual blinders.

First, there are Pink Tide programs that are not resounding successes but that cannot be considered failures with regard to the goal of achieving structural change. It is necessary to make a distinction between Pink Tide policies that point in the direction of far-reaching change, such as the creation of spaces for popular participation, as opposed to token programs amounting to public relations ploys. The significance of the former cannot be written off because of their limited effectiveness or for not having succeeded in replacing existing institutions of the old order. Examples include the numerous cooperatives and communes established in Venezuela and organs of participation in political decision-making in Brazil, Uruguay, and elsewhere, all of which involved large numbers of participants.38 Along these lines, Chris Gilbert, in his study of Venezuela’s communal movement, writes “I am delighted by the headway made by the red flag in this commune [El Maizal] because it points to the persistence of very ‘red’ elements in the so-called Pink Tide.”39

Social movements play key roles in promoting popular participation. Prominent scholars of social movements have long underlined the importance of “friendly” governments in stimulating their growth.40 The observation is particularly applicable to Pink Tide countries that were previously characterized by brutally repressive regimes and where the far-right, if it returns to power, will undoubtedly repress social protests in ever more extreme forms. These variables raise the issue of how to judge governments (like that of Lula) that encourage social movements while not satisfying their more ambitious demands, such as land redistribution.

Second, defensive strategies sometimes succeed from a political viewpoint, but other times fail miserably. Maduro’s defensive strategy of concessions to the private sector, for instance, was successful in that it allowed him to weather a Washington-backed right-wing offensive. The opposite occurred with former president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s endorsement of the presidential candidate Sergio Massa (rather than youthful social movement leader Juan Grabois) as a means to placate centrists, resulting in the election of Milei. Whereas Minister of the Economy Massa was held responsible for the nation’s triple-digit inflation, Grabois promised to revitalize the Peronist movement, which, he pointed out, was lacking in any kind of political project.41

Third, China, with its success in combating extreme poverty and promoting economic growth, serves as an inspiration for Pink Tide movements in their rejection of U.S.-imposed neoliberal formulas. But is China a good role model for the Pink Tide in its attempt to achieve far-reaching change, as some Latin American leftist champions of “market socialism” contend?42 Certainly, an economic model that takes in many large-scale capitalists cannot be labeled as pure socialism. Pink Tide governments, however, have been characterized by multiclass alliances in which the capitalist class is divided between a minority sector lending various degrees of support to the progressive government and the majority fractions aligned with the right. The alliances with business groups are “tactical” — as opposed to strategic alliances with the so-called “national anti-imperialist bourgeoisie,” as envisioned by the Communist International a century ago. These are tactical because they are fragile and not based on far-reaching goals, and because the capitalist allies are the first to defect when the going gets rough, as occurred in Brazil in 2016 and Bolivia in 2019.

The Argentine Marxist economist Claudio Katz calls these complex, contradictory relationships “antagonistic cooperation,” in which the capitalists of the South, in spite of their “increasing transnationalization,” have “not destroyed their local roots,” and “remain … in competition with the corporations based outside the region.”43 The thesis of anti-Pink Tide writers, including the passive revolution ones, that the Pink Tide has capitulated to global capitalism belies the intensity of these tensions and the “antagonistic” component of the relations. Robinson, for instance, recognizes tensions but minimizes their confrontational aspect. Thus, he claims that the BRICS countries, far from challenging global capitalism, are seeking integration into the system and a greater decision-making voice within its framework.

Fourth, there is the possibility that at a given moment Pink Tide governments can move significantly to the left, similar to what happened in Mexico under Lázaro Cárdenas in the 1930s. The existence of leftist factions within Pink Tide movements, the radicalness of its rank and file, and its legacy of struggle heightens the probability of such a scenario. Another factor enters into play. As the historic leader of Brazil’s MST João Pedro Stédile recently stated, with the deepening of the crisis of world capitalism the Latin American left — including the Pink Tide — is likely to progress from anti-neoliberalism (or what he calls the “neo-developmental, progressive project”) to anticapitalism.44

These and other issues are bound to impact leftist strategy and as such call for open-ended discussion. Passive revolution writing on Latin America, however, concludes that the revolutionary component of the Pink Tide phenomenon has exhausted itself, and that those governments are now inextricably tied to global capitalism and its dominant class fractions. With such an outlook, the richness and uniqueness of Pink Tide experiences are left behind.

The second wave of Pink Tide governments is more moderate than the first, but the extreme opposition of their Washington-supported, right-wing adversaries has not eased. International sanctions imposed on Venezuela and Nicaragua; lawfare used against Pink Tide leaders in Brazil, Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, and Argentina; and the 2019 coup in Bolivia, coupled with the U.S. nurturing of right-wing opposition elements, are not to be ignored. That imperialist aggression has not diminished against the Pink Tide runs counter to the central argument of passive revolution writers that those governments have turned their backs on the social movements that brought them to power. For passive revolution writers, Latin America is moving toward an ever clearer divide between the forces of global capitalism, including governments across the political spectrum that adhere to the “commodity consensus,” on the one hand, and social movements, on the other. In this sense, passive revolution theory has been a poor predictor of what is taking place. The region is much more than states obedient to the dictates of global capitalism pitted against robust, completely autonomous, globally supported social movements backed by revolutionaries on the far left. In Latin America, there is a strategically important middle ground between global capitalism and social movements, a space that is occupied by Pink Tide governments and movements—whose future direction is far from predictable.

- 1

Álvaro Garcia Linera interviewed by Iván Schuliaquer, “In Turbulent Times, Moderation Means Defeat for the Left,” Links: International Journal of Socialist Renewal (November 17, 2023), links.org.au.

- 2

Massimo Modonesi, for instance, viewed Venezuela under Chávez as a partial exception to the Pink Tide in general, due to its participatory democracy, the “level of public financing,” and “strong reformism with a structural scope,” as well as the Chavista government’s promotion of communes. Massimo Modonesi, Subalternity, Antagonism, Autonomy: Constructing the Political Subject (London: Pluto Press, 2014), 164, 174; Massimo Modonesi, The Antagonistic Principle: Marxism and Political Action (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2019), 156. For a similar contrast between Chávez and Maduro, see William I. Robinson, “Venezuela: The Epicenter of the ‘Pink Tide’ and Now of the Right-Wing Rollback,” The Real News, February 20, 2019.

- 3

Nicolas Allen and Hernán Ouviña, “Reading Gramsci in Latin America,” NACLA: Report on the Americas, May 26, 2017; Franck Gaudichaud, Massimo Modonesi, and Jeffery R. Webber, The Impasse of the Latin American Left (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022), 126–27.

- 4

Gaudichaud, Modonesi, and Webber, The Impasse of the Latin American Left, 125.

- 5

As discussed by Franck Gaudichaud, “South America: End of a Cycle? Popular Movements, ‘Progressive’ Governments and Eco-Socialist Alternatives,” International Viewpoint, December 10, 2015.

- 6

Raúl Zibechi, “Argentina from Below,” Autonomies (blog), November 29, 2023, autonomies.org.

- 7

Modonesi, Subalternity, Antagonism, Autonomy, 156, 165.

- 8

Adam David Morton, “The Continuum of Passive Revolution,” Capital & Class 34, no. 3 (2010): 329.

- 9

Modonesi, Subalternity, Antagonism, Autonomy, 167; Massimo Modonesi interviewed by Mariana Bayle and Nicolas Allen, “Fourth Transformation or ‘Transformism’?,” Historical Materialism (August 28, 2019).

- 10

Jeffery R. Webber, “Evo Morales and the Political Economy of Passive Revolution in Bolivia, 2006–15,” Third World Quarterly 37, no. 10 (2016): 1872.

- 11

Modonesi, The Antagonistic Principle, 145–46, 153–54.

- 12

Modonesi, The Antagonistic Principle, 146–47; Webber, “Evo Morales and the Political Economy of Passive Revolution in Bolivia,” 1860; Morton, “The Continuum of Passive Revolution,” 317.

- 13

Morton, “The Continuum of Passive Revolution,” 317–18; Steve Ellner, “Objective Conditions in Venezuela: Maduro’s Defensive Strategy and Contradictions among the People,” Science and Society 87, no. 3 (2023).

- 14

This is the case with Svampa. See Modonesi, The Antagonistic Principle, 147; Steve Ellner, “Prioritizing U.S. Imperialism in Evaluating Latin America’s Pink Tide,” Monthly Review 74, no. 10 (March 2023): 44.

- 15

Webber, “Evo Morales and the Political Economy of Passive Revolution in Bolivia,” 1860.

- 16

Chris Hesketh, Spaces of Capital/ Spaces of Resistance: Mexico and the Global Political Economy (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2017), 69–70.

- 17

William I. Robinson, “Passive Revolution: The Transnational Capitalist Class Unravels Latin America’s Pink Tide,” Truthout, June 6, 2017.

- 18

Carlos Nelson Coutinho interviewed by Jornal do Brasil, “Socialism and the Workers Party in Brazil,” Rethinking Marxism 16, no. 4 (2004): 403; João Machado and José Correa Leite, “Brazil after Four Years of Lula,” Against the Current, no. 127 (March/April 2007).

- 19

Steve Ellner, “Introduction: Progressive Governments and Social Movements in Latin America: An Alternative Line of Thinking,” in Latin American Social Movements and Progressive Governments, Steve Ellner, Ronaldo Munck, and Kyla Sankey, eds. (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2022), 14–15.

- 20

Webber, “Evo Morales and the Political Economy of Passive Revolution in Bolivia, 1857–60;” Jeffery R. Webber and Barry Carr, “The Latin American Left in Theory and Practice,” in The New Latin American Left: Cracks in the Empire, Jeffery R. Webber and Barry Carr, eds. (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2013), 9–10.

- 21

Ellner, “Progressive Governments and Social Movements in Latin America,” 23–24; Ellner, “Objective Conditions in Venezuela,” 410.

- 22

Gaudichaud, Modonesi, and Webber, The Impasse of the Latin American Left, 68, 124; Mike Gonzalez, The Ebb of the Pink Tide: The Decline of the Left in Latin America (London: Pluto Press), 66–71, 95, 105, 179.

- 23

Jeffery R. Webber, “Managing Bolivian Capitalism,” Jacobin, January 12, 2014; Jeffery R. Webber, “Bolivia’s Passive Revolution,” Jacobin, October, 29, 2015.

- 24

Robinson, “Passive Revolution.”

- 25

Gaudichaud, Modonesi, and Webber, The Impasse of the Latin American Left, 110.

- 26

Morton, “The Continuum of Passive Revolution,” 319, 333–35; Panagiotis Sotiris, “Revisiting the Passive Revolution,” Historical Materialism 3, no. 3 (2022): 4.

- 27

In his analysis of Maduro, Marxist scholar and Pink Tide critic Mike Gonzalez turns to Marx’s writing on Bonapartism, in which the state in the face of intense class conflict distances itself from classes but achieves a degree of stability at the expense of the aspirations of the popular sectors. He also cites the concept of passive revolution. Gonzalez, The Ebb of the Pink Tide, 102, 176. Modonesi applies the same concept to Ecuador under Rafael Correa, and Robinson to the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. See Modonesi, The Antagonistic Principle, 147–48; William I. Robinson, “Nicaragua: Daniel Ortega and the Ghost of Louis Bonaparte,” Against the Current (November–December 2022).

- 28

Italy’s passive revolution began in the aftermath of the First World War, after Benito Mussolini had abandoned his socialist positions and was expelled from the Socialist Party for supporting Italian participation in the war.

- 29

As quoted in Sotiris, “Revisiting the Passive Revolution,” 17. A fundamental distinction needs to be made between a process in which the bourgeoisie achieves hegemony—one consisting of a military-led “revolution from above”—and one consisting of leftist-inspired reformism from above (as analyzed by Coutinho, who denied that passive revolution necessarily involves hegemony and consensus).

- 30

Jeffery R. Webber, “Contemporary Latin American Inequality: Class Struggle, Decolonization, and the Limits of Liberal Citizenship,” Latin American Research Review 52, no. 2 (2017): 291.

- 31

Modonesi, The Antagonistic Principle, 149, 154; Chris Hesketh, “A Gramscian Conjuncture in Latin America?: Reflections on Violence, Hegemony, and Geographical Difference,” Antipode 51, no. 5 (2019): 1486.

- 32

William I. Robinson, “The Unbearable Manicheanism of the ‘Anti-Imperialist’ Left,” The Philosophical Salon, August 7, 2023.

- 33

“BRICS Invite Is ‘Great Opportunity’ for Argentina, Outgoing President Says,” Al Jazeera, August 24, 2023.

- 34

William I. Robinson, “The Transnational State and the BRICS: A Global Capitalism Perspective,” Third World Quarterly 36, no. 1 (2015): 5.

- 35

Robinson, “The Transnational State and the BRICS,” 18.

- 36

Robinson, “The Transnational State and the BRICS,” 2–3, 5.

- 37

Robinson, “The Transnational State and the BRICS,” 18; Robinson, “The Unbearable Manicheanism of the ‘Anti-Imperialist’ Left”; “Interview with PEWS Chair Bill Robinson,” PEWS News 14, no. 1 (2014), 6; Patrick Bond, “BRICS Banking and the Debate over Sub-Imperialism,” Third World Quarterly 37, no. 4 (2016): 622.

- 38

Ellner, “Progressive Governments and Social Movements in Latin America,” 11–13.

- 39

Chris Gilbert, Commune or Nothing!: Venezuela’s Communal Movement and Its Socialist Project (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2023), 50.

- 40

Peter K. Eisinger, “The Conditions of Protest Behavior in American Cities,” American Political Science Review 67, no. 1 (1973): 26–27.

- 41

José Pablo Criales, “Juan Grabois: ‘El Peronismo ya no tiene un proyecto,'” El País, December 13, 2023.

- 42

Steve Ellner, “Maduro and Machado Play Hardball,” NACLA: Report on the Americas (Spring 2024): 10.

- 43

Claudio Katz, “Dualities of Latin America,” Latin American Perspectives 42, no. 4 (2015): 15; Claudio Katz, “Latin America’s New ‘Left’ Governments,” International Socialism 107 (Summer 2015).

- 44

Al Mayadeen, “Without Struggle, There Is No Victory,” Peoples Dispatch, April 29, 2024. Works by Ernesto Laclau and others on the relationship between populism and crisis, and on the potential of populist movements in power to move in a far leftist direction in situations of crisis, reinforce my position on the unpredictability of the Pink Tide phenomenon. See Ernesto Laclau, Politics and Ideology in Marxist Theory: Capitalism-Fascism-Populism (London: Verso, 2012); Benjamin Moffitt, “How to Perform Crisis,” Government and Opposition 50, no. 2 (2015): 191–95.