Another Olympics is possible: the socialist sports movements of the past

For more discussion of issues surrounding sport and politics, click HERE. For more on the Olympics, click HERE.

August 7, 2012 – As Mike Marqusee points out in an article posted at Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal, the modern Olympic Games are "a symbolic package: individual excellence at the service of the nation-state under the overlordship of multinational capital". Today, the domination of most sport by the capitalist corporations, crude nationalism and dog-eat-dog ideology is almost complete, occasionally challenged by the actions a few principled groups and individuals. But that was not always the case.

In fact, in the early decades of the 20th century, there were mass socialist-inspired workers' sports movements that sought, to varying degrees, to challenge capitalist control and ideology in sport. The goal was to organise working-class people through sport and leisure, and in some cases to attempt to fashion a new conception of sport.

Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal has gathered the following articles to illustrate various aspects of this almost forgotten, but important, episodeof working-class history.

The modern Olympics and the triumph of capitalist sport

By John Nauright, co-director, the Center for the Study of Sport and Leisure in Society, George Mason University

Virginia, USA

August 6, 2012 – History Workshop – As the world turns its attention to London for the 2012 Summer Olympic Games, it is worth remembering that the modern Olympics represent the ultimate triumph of capitalist sport and not the “ideals” that are presented to the global audience.

The Olympic Games are run by an elite private organisation, the International Olympic Committee (IOC), which has succeeded in stamping out all other “Olympic” games and movements as it is the self-proclaimed great unifier of the world through “Olympic” sport. The IOC owns the rights to use the word “Olympic” and no event beyond of its control can use the word without permission due to its licensing agreements and penchant for using legal systems to protect the name. The IOC has a long history of using its power to marginalise others and has been faced with numerous scandals over the past 20 years.

Of course there is much to celebrate as athletes from around the world gather to compete for their native or chosen country [i]. These athletes have trained for many years to reach the top of their sport and have worked hard to reach their goals. However, do not be surprised to see the top nations on the medal table align closely with the past several summer games [ii].

Elitist

The modern games emerged as a borrowed vision of Baron Pierre de Coubertin of France. He was enamored with English games playing and visited the Much Wenlock “Olympic” Games in 1890. Founded by Dr William Penny Brookes in 1850, the Much Wenlock Games were a means to promote the “moral, physical and intellectual improvement of the inhabitants of the town and neighbourhood of Wenlock”, a small town in Shropshire. Professionals were allowed to participate in the Much Wenlock Games as of 1868 and events were handicapped in 1869. De Coubertin was so impressed that he moved forward with an idea to revive the ancient Greek Olympic Games, organising the first Olympic Congress in 1894, which decided to hold an Olympic Games in Athens, Greece in 1896 [iii].

Unlike Much Wenlock and earlier regional sporting festivals, the modern Olympics were elitist, amateur, and initially male only affairs directed by an organisation of male aristocrats and other social and economic elites from Europe and European descendants from various settler societies. At the time the modern games began “amateur” was defined in ways to create class exclusion rather than our more contemporary understanding of someone who is or is not paid to play the game.

In the 1890s sports organisations grappled with the class issue with some adopting open professionalism (association football, rugby league), some remaining amateur (rugby union, Olympic sports), and even some mixing amateurism and professionalism (cricket). Nearly all of these organisations remained for men only, though some women slowly made their way into a few of the Olympic sports.

Throughout much of the 19th century poorer rural and urban working-class men played sport in isolation from the sports played by the landed gentry and bourgeois classes. In some sports large sums of money could be made through the winning of prizes or wagers, particularly in “pedestrianism” and rowing. Football games, played in the streets, villages and on farmland, also continued to be played by young males throughout England and beyond. Some factory and business owners, particularly in the confectionary industry, supported their workers participating in sports and other physical activities – primarily to promote hygiene – though others feared too much playing at sports could lead to injuries and come at a cost to productivity.

Workers' sport

Workers' sport organisations became popular in the first decades of the 20th century. Initially workers formed their own sports teams, such as the football club founded by workers at the Woolwich Arsenal works, today’s Arsenal F.C. Later competitions between groups of workers were held ultimately leading to the formation of the social-democratic Worker Sport International, founded in Lucerne, Switzerland in 1920 (later changing its name to the Socialist Worker Sport International [SASI] in 1925).

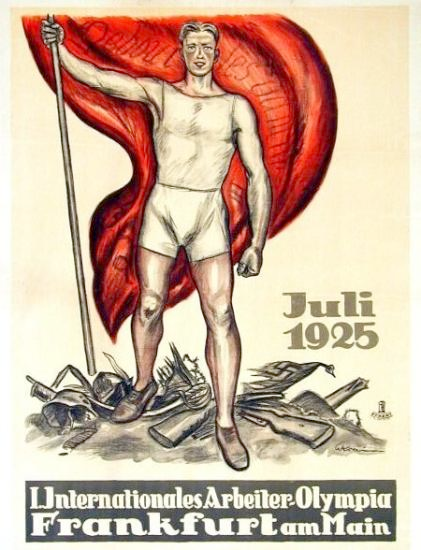

Not to be outdone by the socialists [social democrats], communists responded by forming the Red Sport International in Prague, Czechoslovakia in 1921. Socialist workers held a Winter Olympiad in Schreiberhau, Germany in February 1925 and a summer event in July 1925 in Frankfurt, Germany, in which more than 100,000 athletes participated and where 3000 athletes from 12 countries competed in official events. We know that the German women’s relay team broke the existing world record in their sprint relay, but the International Amateur Athletics Federation (IAAF) refused to recognise it since it did not sanction the event [iv].

A second summer Olympiad of workers took place in Vienna in 1931 with 77,000 athletes from 17 countries participating in front of more than 200,000 spectators. At that time the SASI boasted of more than 2 million members in workers' sports clubs internationally, though over half of these were in Germany.

In 1935 the socialist and communist worker sports movements began to work together. Workers planned to hold another “Worker Olympics” in Barcelona in 1936 to counter the Nazi-controlled 1936 Berlin Olympic Games of the IOC. Athletes from 11 countries had planned to participate, but the Spanish Civil War intervened. Many athletes stayed on to fight the fascists in Spain.

IOC consolidates

Once the fascists took over in Spain, one of their leaders was none other than Juan Antonio Samaranch, who assisted Franco as governor of the Barcelona region and who was president of the IOC from 1980 to 2004. The Worker Olympiad events were so successful that the Popular Front government in France financially supported French teams for Barcelona and Berlin in 1936. A combined event involving socialist and communist workers was held in Antwerp in 1937 involving another 30,000 participants and 100,000 total spectators.

After World War II, the IOC consolidated its position as the custodian of the “Olympic” traditions and name in part enabled by the decision of the Soviet Union to enter its events beginning in 1952. The Soviet regime decided to utilise the Olympics as a venue to demonstrate its superiority. In many European countries the impact of the war left workers' sports organisation in disarray and without funds or adequate facilities. The rule that only one governing body for sport would be recognised by international federations and the IOC made it doubly difficult for workers' sports organisations to gain traction.

Corporate takeover

During the 1960s the majority of people around the world engaged with the Olympics through the medium of television. More and more money entered the Olympics as a result of global television coverage and national governments viewing the Olympic Games as valuable public relations exercises, leading the IOC to remove amateur restrictions enabling professional athletes, many of whom earned large sums of money, to compete openly.

By the 1990s, cities spent small fortunes in hopes of hosting the games and millions and even billions to build facilities for the games in the hopes of gaining global publicity, increases in tourism and legacies for future generations. The distribution of costs and benefits has been vastly uneven, however.

Today the Olympics represent the triumph of the neoliberal global capitalist sports system based on a global economy of sports centered on a sports-media-tourism complex where professional sports leagues and regional and global international sporting competitions circulate among an elite few. These mega-sporting events have their brands and income protected via a vast machinery of contractual obligations that subvert democracy and human rights and impose significant burdens on local economies.

Former Australian Prime Minister John Howard argued in the 1990s that criticism of the Olympics was “un-Australian” in efforts to minimise protests against the requirements for Sydney 2000 and the country had to implement to satisfy the IOC. Protest and vigourous debate are hallmarks of the Australian tradition. Similarly in Britain, the London Olympic Games and Paralympic Games Act of 2006 exacts even tighter control over what can and cannot be done or said in the lead-up to the event and during the event itself.

Who will benefit from the London event? The small shopkeepers and local hawkers and traders? Global capitalist enterprises? The British economy? The athletes? We know for sure that the IOC and its group of elite global corporate sponsors will top the list. Today sport appears more and more popular yet less and less accessible.

Notes

[i] Many athletes in 2012 will represent countries that they have moved to in order to compete in their sport, some through inducements, others through choice based on a number of factors. In a recent list of Team Great Britain’s top 10 medal hopes in athletics (track and field), three fit this category including one from the USA.

[ii] These have been USA, Russia, China, Germany, Australia, Great Britain, France and Italy.

[iii] For more on Much Wenlock and British antecedents of modern sporting festivals see, M. Polley, The British Olympics: Britain’s Olympic Heritage, 1612-1912 (London: English Heritage, 2011). The best account of Baron de Coubertin and the rise of the modern Olympics is J. MacAloon, This Great Symbol: Pierre de Coubertin and the Origins of the Modern Olympic Games (London: Taylor & Francis, 2008, new edition).

[iv] For more detail on these games and European workers' sports movements, see A. Krueger & J. Riordan (eds.), The Story of Worker Sport (Champaign: Human Kinetics, 1996).

Doing it better than our enemy

By Ben Lewis

July 26, 2012 – Abridged from Weekly Worker

’Tis right as England beat the rest

Of Europe and the world at all things

That so her sports should be the best

And England first in great and small things

No German, Frenchman or Fijee can ever master cricket, sir

Because they haven’t got the pluck to stand before the wicket, sir1

Living as we do, in this strange time known as "London 2012", this popular rhyme from late 19th century Britain might sound all too familiar to many Weekly Worker readers currently up to their necks in state-sponsored Olympic fever. Of course, the BBC and other media outlets will now speak of "Britain", not "England", and the "Britain first" agenda no longer deploys terms like "Fijee". But nonetheless, the media offensive has an all-too-obvious focus: British medals, British pluckiness and British pride. In these times of depression and austerity, the nation -- black, white, rich, poor – should "unite as one" against the others.

Stirring the emotions and captivating hearts and minds, international competitive sport can certainly be exploited for such nefarious, chauvinistic purposes – and enormous profits and revenue along the way. Historically, this had led to conscious decisions and organisational manoeuvres on the part of the capitalist class to fashion sport in its own interest. Today, behind the deft flicks of German footballer Mesut Özil, the sumptuous timing of Indian cricket batter Sachin Tendulkar or the astounding stamina and pace of Kenyan marathon runner Patrick Mackau lurks a Byzantine empire of lucrative television contracts, ubiquitous advertising and farcical sponsorship stipulations.2 This is just another manifestation of capitalism’s unique ability to reduce everything to commodities.

But is there something intrinsic to sport that makes it uniquely reactionary and irredeemably prone to nationalistic narrow-mindedness? Is sport something immutable that stands above the balance of class forces and social relations more generally? And what, if anything, does Marxism have to say about the world of sport and recreation?

Many on the left – far too many unfortunately – dismiss sport altogether. After all, why should the working class be wasting its time lifting weights or watching football when there are so many other things to be getting on with?

In his 1996 article, "Marxism and sport", Chris Bambery, argued that sport simply distracts the working class from what it should really be doing: i.e., trade unionism, low-level "united front" work and reading dull-as-ditchwater left publications that pretend to speak to the "masses". For him, sport is just a kind of modern-day “opium of the masses”, where those like Özil, Tendulkar and Mackau are the new gods. “Naturally,” he remarks, in a distinctly elitist fashion, “socialists understand why people take part in or watch sport. It is an escape from the harsh world in which we live. That is why we do not ignore sport. Rather socialists campaign, for instance, against racism on the terraces and seek the support of sportsmen and women for such campaigns. Neither would socialists dream of banning or prohibiting participation in sports.”3 Well, that’s a relief.

That is not to say that comrade Bambery’s observations about the current nature of sport as an alienated form of self-expression and entertainment are off the mark. There is no doubt that sport does provide solace for millions of people. It certainly can divert and divide our class, forcing us to passively consume what are essentially tightly marketed products (clubs, players and competitions, as well as individual events) rather than actively engage in and exercise control over them.

The problem, however, is that Bambery essentially outlines a bourgeois conception of sport. The status quo is more or less the best that we proles can hope to achieve under capitalism: i.e., a form of entertainment that tames and pacifies the population, all the while serving as a means of rallying people to the nationalist banner and providing fit and healthy soldiers for imperialist wars.

He fails to even entertain the notion that sport, like so many other things in society, is reflective of social forces more generally and a site of struggle. And he certainly does not think that sport could provide soldiers for the class war.

A different approach

We must turn to Fritz Wildung, a German social-democratic pioneer of workers' sport, for a rather bolder vision: "Sport in the interests of the working class means sport that liberates the worker.”4 These were the founding ideas behind the phenomenon of mass workers' sport in the early 20th century .

Lorenz Peiffer argues that workers' sport has been “persecuted, banned, repressed and forgotten”5 -- perhaps explaining why many on the left do not take this important aspect of our history very seriously. Following decades of defeat it has been washed from our memory. Most people express genuine disbelief when they hear that our movement once successfully ran its own sporting clubs, associations, cooperatives and even international festivals to rival the Olympic Games. As such it is to be welcomed that Simon Basketter, writing in a post-Bambery Socialist Worker, considers that the “attempts to organise workers’ sport are worth remembering”.6 Ditto his argument that sport became a “battleground” in the class struggle.

Struggle is indeed key. In the face of bourgeois attempts to seize control of late 19th century sport through crowd control, ticket sales, nationalist propaganda and so on, our class fought back and organised. Thus the struggle for independent working-class sport was born – seen as an essential component of the struggle to refashion society and an integral part of the workers’ full and rounded development: a healthy body and a healthy mind. It is thus no surprise that the continental roots of workers' sport can be traced back to the formation of workers' educational associations there.

With the rise of national trade union federations, cooperatives and mass socialist parties during the period of the Second International (1889-1916), workers' sport started to assume organisational form. As with so many other aspects of working-class culture, the German working-class movement served as a model – its enormously popular gymnastics, cycling and hiking associations were replicated all across Europe. Workers' sport encompassed a wide-range of activities ranging from chess to jiu-jitsu.

The emphasis was always on participation – another way of patiently building the organisational capacity of our side, opposing the dominance of capital and breaking through the fetters it imposes on the self-expression of the worker. These clubs and associations often produced and distributed their own agitational materials and even specialist publications.

Reflecting the post-World War I division in the workers’ movement, two workers' sport internationals came into existence in the early 1920s. The Lucerne Sport International (LSI), founded in 1920, built on the remnants of official social democracy. Nevertheless, its membership totalled nearly 2 million people, with more than half of these coming from Germany. The German movement had the honour of running the largest cycling club in the world, served by a cooperatively run bicycle factory. While much smaller, the Austrian and French sections were also influential.

The Communist International helped found the International Union of Red Sports and Gymnastics Associations – more commonly known as the Red Sport International – in 1921. Its explicit aim was “the creation and amalgamation of revolutionary proletarian sports and gymnastics organisations in all countries of the world and their transformation into support centres for the proletariat in its class struggle”.7 The fate of both organisations was bound up with the twists and turns of the relationship between the two wings of the international workers’ movement. At a grassroots level, however, the relationship between the two organisations was often close and led to some interesting outcomes.8

Worker Olympics

Following a series of large regional and local events, the first Worker Olympics took place in Frankfurt am Main in July 1925, organised by the LSI. Despite the fact that the festival banned communist sporting organisations from taking part, these games were a big success. More than 100,000 athletes competed, making them the biggest Olympic event ever. Frankfurt 1925 highlighted the schism between the (class-prejudiced) "amateurism" of the official Olympic Games and the working-class response to them. A line had been drawn – there were no common events or competitions between the two Olympics. (In other sports, however, there were examples of competition – on one occasion the Austrian workers' football team actually beat the official Austrian national side. Forget Liverpool vs Everton: that’s a real derby!)

In welcome distinction to the usual capitalist crap, the official motto of Frankfurt 1925 was “no more war” – sticking two fingers up to the official Paris games of 1924: the warped and jingoistic values informing the latter ensured that athletes from the "loser" countries in World War I were banned from taking part, not to mention athletes from the young USSR. The LSI charged Paris 1924 with “using sport to promote war”. While the Second International’s record in fighting World War I was anything but exemplary, the message of the LSI games was clear: “For sure, competition easily awakens animal instincts. But only if the spirit of humanity is absent. Nationalists know no humanity. We all have the same enemy: capitalism.”9 More than 150,000 spectators attended the workers' games, which eschewed national flags and anthems. Memorable events included a “living chess game” and an anti-war demonstration on the “day of the masses”. The games finished with the (hugely popular) football final and an aquatic exhibition in the Main river! Later on that year the first workers' winter games took place – also in Germany.

Calisthenics were an important part – all competing athletes were expected to participate in these mass exercises. In this way the workers' Olympics strove to break down the artificial division between the athlete and the spectator – and to counter national chauvinism by bringing together so many athletes from around the world in a conscious display of international solidarity. The aim was to proclaim the “new great power” on the global scene: the international working class.

Social-democratic "Red Vienna", renowned for its daring, avant-garde experiments in architecture and the design of working-class accommodation, was the venue for the second LSI workers' Olympics. The Prater Stadium had been built especially for the occasion. More than 250,000 people watched the “festive march”. All this was a bit of a coup for the Second International too, with its 1931 Vienna congress taking place at the same time. The event’s official program even contained “welcome greetings” from such Second International luminaries as Austro-Marxist Victor Adler and the execrable Belgian social chauvinist Emile Vandervelde.

Once again, the festival’s opening ceremony was remarkable, featuring a live depiction of the history of the workers’ movement from the Middle Ages. At its close, a large model of a capitalist’s head placed in the middle of the Prater stadium collapsed into itself (imagine that, Seb Coe!).

All the while, the communist RSI and its affiliates, such as the wonderfully titled Combat Association for Red Sport Unity (Germany), were organising their own events as an alternative to both the official games and those of the LSI. The first Worker Spartakiad took place in Moscow in 1928, followed by a Winter Games in Oslo. Moscow 1928 could not compete with the LSI event in terms of numbers (600 athletes representing 14 countries), but it was nonetheless a crucial event for communist workers' sport and its attraction internationally.

In 1932 the RSI attempted to take the second Spartakiad to Germany, but in the heightened political atmosphere of the time the games were banned. Then came fascist reaction in Germany and Austria. It is worth noting that Hitler crushed the worker sport organisations in Germany in 1934.

Fascism struck another blow against the workers' Olympics in 1936. With Comintern’s embrace of popular frontism, there were successful attempts to organise a joint RSI-LSI Olympics in Spain. However, these games had to be cancelled immediately after the opening ceremony following Franco’s uprising. With much of Europe now coming under the influence of fascist reaction, brave attempts were made at organising another event in the following year, this time in Antwerp, but in spite of the unity of the two organisations the numbers were markedly down. The repression in the core country of workers' sport had taken its toll. Nevertheless 50,000 spectators at the opening ceremony was no mean achievement. And once again the games had tremendous symbolic value, especially for the many courageous working-class militants engaged in the struggle against fascism. There was even a Spanish delegation present despite the civil war. Their armoured car and "No pasaran" banners were met with cheers from the crowd.

This was the last time that a workers' Olympics was organised on an international scale. In line with post-war "peaceful co-existence", "official" communism [Stalinism] soon fell in behind the mainstream games -- as did official social democracy, by then fully integrated into the US-led global order. The split between the bourgeois Olympics and workers' Olympics was resolved in favour of the former. And this situation looks set to continue until we see a revival of mass working-class organisation.

Do it better

Seventy-five years on, we ought to look back on these events with great pride. With organisation, our class can achieve so much. Yet it has to be said that workers' sport was not without its problems: after all, both the RSI and LSI ultimately failed. As we might expect, the workers' sport movement has not been the subject of great study, but the research that has been undertaken has highlighted some significant shortcomings in the communist RSI – even before Stalinisation and Soviet sport’s degeneration into the cult of steroids, Stakhanovite biceps and the worship of targets.

André Guenot’s essay on communist sport makes some interesting observations10. The RSI was hastily set up to counter the influence of the dominant LSI among the masses, but its role was not entirely clear: at first it was subordinate to the Young Communist International: i.e., treated as youth work. This led to a dispute, with Comintern ultimately siding with the YCI over the RSI. Only in 1924, at Comintern’s fifth congress was the RSI officially recognised as a constituent part of the communist movement.

Gunot notes an ensuing tension in the RSI’s identity. On the one hand, RSI congresses were filled with Communist Party members and promoted communist policy on sport. On the other, it wanted to be a "broad" organisation seeking to win over non-communist elements. Indeed, most of its followers were not CP members. However, especially with increasing bureaucratisation, this led to a growing gulf between the party and the (overwhelmingly non-communist) rank and file, who were increasingly excluded from decision making and the actual politics of the RSI. This often ensured that many workers' sport activists often chose their particular sporting international not on the basis of the difference between reform and revolution, however understood, but on the basis of how it would impact on the organisation of their sporting competitions, leagues etc. There is a sense in which both the LSI and the RSI simply provided a space for well-organised and rewarding sport on the periphery of capitalist society, rather than challenging bourgeois conceptions of sport or society more generally.

In a certain sense, the German expression Sport und Körperkultur (Sport and physical culture) nicely captures what I think should be the aim: the promotion of sport as part of our culture, whether that takes the form of competitive sports (up to and including with "mainstream" athletes) or simply as a way of our class getting together and enjoying a hike/bicycle ride/cricket match.

There can be no doubt about sport’s socialising – and politicising – role if it is rooted in a culture of democracy, self-activity and self-organisation. A class that spends its "free time" in front of the television as isolated, passive consumers of activity that is totally alienated from their control or direction does not make for a political, thinking movement. This is why the emphasis on rounded development and self-improvement in workers' sport is so important – an integral part of the revolutionary project of human self-emancipation.

Clearly, much more thinking needs to be done on this question, and studying our rich past in more detail ought to be an essential part of this. I would stress that, while a communist program should advance demands on the state (sport as part of a polytechnic education, the provision of quality sports facilities), we should primarily look to building our own organisations: trade unions, cooperatives, sports associations and so on. These organisations should try to encompass the class as a whole, with democratic, self-activating structures within which communists can organise and have an influence.

Even today there are some examples of workers' sport: trade union five-a-side tournaments, cooperatively run sports clubs, the well-organised left-wing "ultra" fans in clubs like Sankt Pauli in Hamburg. But in truth these are small, often isolated examples. We are a long way from the kind of international coordination required to follow in the footsteps of the workers' sport activists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Yet even in its current emaciated state, the workers’ movement internationally certainly presides over the resources to organise sporting clubs, festivals and even counter-Olympic festivals that could rival and – within time – even outdo the "official" games. Obviously one huge obstacle to making that a reality is posed by the fact that our movement, rather like the official Olympics festivities themselves, is presently ideologically and organisationally tied to the organic hierarchy of nation-states that is the imperialist world order.

Two positive lessons we can certainly draw on are that the movement was founded on mass class organisation at base – upon a vision, however distorted, of the working class not as a slave class at the point of production, but as a potential future ruling class that needed to develop its own stance on all social questions. In this sense, many on today’s far left have a political vision that is more conservative than that of Adler or even Vandervelde.

Organising our class and equipping it for struggle is a task to be conducted both at and beyond the workplace. Our movement must be bold and daring in advancing solutions for all areas of society: in sport, leisure and culture more generally, we should aspire to emulate the words introducing the official program of Frankfurt 1925: “We want to show our enemies that we can do it better”.11

The bourgeoisie and its hirelings have, for now, got the upper hand. But, as London 2012 kicks off, it is worth bearing in mind that our side has everything to play for.

Notes1. Quoted in M. Hoskisson, "Capitalism and sport", Permanent Revolution summer 2010. Comrade Hoskisson provides a useful summary of capitalist designs on sport in the late 19th century.

2. For example, Olympic spectators will not be able to eat chips at the Olympics – unless they buy them from McDonald's, of course! Worse, perhaps, was the ban on German beer (!) at the special "spectator zones" during the 2006 football World Cup in Germany. Budweiser should be thanked for that particular stroke of genius.

3. Chris Bambery, "Marxism and sport", Socialist Review December 1996. Comrade Bambery must also take the gold medal for philistinism on the nature of competitive sport too. In true Eugen Dühring fashion, he states: “Under socialism there will be physical recreation – but not sport … Socialism will not be a society where 22 men still play football (far less where another 30,000 people will pay to watch them) or men and women crash up and down a swimming pool competing against each other and the clock. Physical recreation and play are about the enjoyment of one’s body, human company and the environment.” Bambery’s take on competition is comprehensively critiqued in L. Parker "Balls to worker sport?", Weekly Worker, June 12, 2008.

4. Quoted in the "Weblexikon der Wiener Sozialdemokratie": www.dasrotewien.at/arbeiterolympiade.html. This emphasis on the link between mental/physical health and revolution was a common one in Second International Marxism. Although dealing with the "woman question" specifically, August Bebel’s Woman under socialism (1879) is a good example of such an approach.

5. L. Peiffer, "Review of The story of worker sport", Journal of Sport History summer 1997, p. 218.

6. S. Basketter, "A league of our own: the story of the workers’ sports movement", Socialist Worker, July 10.

7. A. Gounot, "Sport or political organization? Structures and characteristics of the Red Sport International,1921-1937", Journal of Sport History, spring 2001, p. 23.

8. One example cited by Gounot is that following the split in the French workers' sports movement almost all the clubs in and around Paris joined the Red Sport International, regardless of whether they were made up of Socialist Party or Communist Party sympathisers. They wanted to keep their sporting events and league tables intact.

9. "Vorwort" in the "Internationales Arbeiterolympia Festbuch", Frankfurt am Main 1925.

10. A. Gounot, "Sport or political organization? Structures and characteristics of the Red Sport International,1921-1937", Journal of Sport History, spring 2001, pp. 23-39.

11. "Internationales Arbeiterolympia Festbuch", Frankfurt am Main 1925, p. 5.

Socialist sports in Yiddish: The Bundist sport organisation Morgnshtern in interwar Poland

By Roni Gechtman

Outlook – The Morgnshtern ("Morning Star" in Yiddish, also known by its Polish name Jutrznia) was the sport organisation of the Jewish Labour Bund in Poland between the two world wars. Founded in 1926 as the Polish-Jewish section of the Socialist Workers' Sport International (SWSI), the Morgnshtern achieved immediate popularity, boasting 5000 members and more than 170 branches in cities and towns throughout Poland. In the 1930s, it was the largest Jewish sport organisation in Poland. The aim of the Morgnshtern was to put in practice the key Bundist principles (socialism, working-class consciousness, internationalism, Yiddish culture and the rejection of militarism and nationalism) in the specific area of sport.

The Morgnshtern's activities were inspired by the theory of workers' sport formulated by the Austro-Marxist Julius Deutsch, at the time chair of the SWSI. In 1928, Deutsch published Sport and Politics, a manifesto of workers' sport, soon translated into Yiddish and most other European languages. Deutsch was a Marxist, but he was neither deterministic nor overly optimistic: he believed that socialists must organise the masses of workers, especially the proletarian youth, and prepare them for the class struggle through education.

For Deutsch, there was no greater error than to believe that the proletariat would bring the class struggle to a victorious end regardless of its moral and cultural situation. Thus, the first tasks of the socialist movement were to free the proletariat from the prison of ignorance in which it was kept by the bourgeois order, and to counteract the influence of bourgeois values transmitted through the media, the compulsory school system, the arts. The beneficial effects of sport activities on a mass scale would have a significant impact on the ongoing class struggle in society.

Class contradictions were evident in sport just as in the rest of society. Deutsch stressed that bourgeois sport reflected bourgeois culture and bourgeois ethical principles. Under bourgeois hegemony, sports were becoming increasingly competitive, individualistic and professionalised. Notions of quality and return in sport paralleled those of the stock market. Moreover, bourgeois sport federations at the time were becoming increasingly nationalist and combative. In many countries sport clubs were coming to resemble fascist parties and even creating fascist militias, attracting some "naïve" workers. Bourgeois sports organisations tried to promote a false sense of harmony between labour and capital and blamed the organised working class for disrupting "national unity".

Deutsch did not condemn professional athletes as individuals; on the contrary, he believed that they might be honest people earning their living in an honourable way, like artists or musicians, but that their performance was meaningless. The professional athlete could impress the audience, but not act as its role model, since his or her achievements resulted from exceptional physical characteristics and specialised training, and this special training was not desirable for everybody, since most professional athletes developed some muscles at the expense of others.

Thus, Deutsch concluded, it was imperative to create separate proletarian sport organisations that would develop sport activities under completely different principles: workers' sport must be "collectivist" and seek improvements in performance by means other than competition; it should not focus exclusively on the training of potential champions, nor make record breaking its main goal, but offer everyone the possibility of practicing sports. Workers' sport must have as its ideal the harmonious development and strengthening of the whole body; it should be practiced in a communal and friendly atmosphere free from any manifestation of violence or brutality. Strategically, a crucial goal of proletarian sport was to mobilise the masses of young workers to join the socialist movement.

The Morgnshtern tried to organise its activities according to Deutsch's principles in the context of Polish Jewry. Though decidedly Jewish, the Morgnshtern was a secular institution. Many of its activities were held on Saturdays and Jewish holidays, which was understandable in an organisation of workers with little leisure time during the week.

Bundists rejected any nationalism, including Jewish nationalism. Throughout its existence, the Morgnshtern produced no formulation equivalent to Max Nordau's famous call for a Muskuljudentum (muscular Judaism). The Morgnshtern membership – male and female Jewish workers engaged in physical work – did not need to prove their muscular and physical skills to counteract an abstract conception of Jews as spiritual or intellectual persons with weak bodies. Moreover, neither the Morgnshtern nor the Bund wanted to transform the Jews into a warrior-people: they rejected both nationalism and war, promoting international solidarity and the creation of a healthier and fairer society for both Jews and non-Jews.

Bundists saw Zionism as a manifestation of bourgeois nationalism and thus refrained from any collaboration with its organisations. The Morgnshtern was openly hostile not only toward the (Zionist) Maccabi, but also toward the (Labour-Zionist) HaPoel. The Yiddish editor of Deutsch's Sport and Politics greeted Deutsch's relative sympathy toward the activities of the HaPoel in Palestine in the 1920s with an ironic remark: "the 'facts' provided by the author – that HaPoel also comprises Arab members – are as accurate as the 'fact' that Jewish trade-unions in Palestine struggle for, and together with, the Arab workers." The irony would not have been lost on Bundist readers, well aware that the Histadrut, the Zionist workers' federation, not only did not represent Arabs but, on the contrary, actively sought to take jobs from Arab workers and give them to Jews.

The Morgnshtern emphasised participation in non-competitive activities, and the majority of its membership belonged to its non-competitive sections. The most popular activity was gymnastics, and after it, the overwhelmingly female-dominated eurhythmics [ritmika]. The incentive for the participants in these activities was not competition but self-improvement. The ritmika report for 1937 stated its main aim as the democratisation of physical activity by giving children who could not otherwise afford it access to physical education. In the summer, the Morgnshtern rented a swimming pool during certain hours to offer swimming lessons to its members. A popular winter activity was glitshn (ice skating), and lessons were also offered at accessible prices, especially for children. Every year from 1933 the Warsaw Morgnshtern rented a skating rink for its members.

The biggest event in the Morgnshtern calendar was the turnfest, a sport and cultural holiday in which displays of harmonic movement of hundreds or thousands of gymnasts represented the proletarian force, unity and sense of solidarity. The program of the 1932 turnfest in Kutno offers an indication of what these turnfests might have looked like. During the event, all the different gymnastic groups, from the youngest to the oldest, and alternating groups of males and females, performed gymnastic exercises in various styles. The last groups to perform were the adult men – performing the same program presented by the Morgnshtern one year earlier at the Workers' Olympic Games in Vienna – and adult women, who performed a series of exercises to the rhythm of popular Yiddish songs ("der rebe elimeylekh" and others). In the last part, all groups together performed a gymnastic piece called "der eybiker korbn" ("The Eternal Victim"), which represented "a symbolic image of the struggle between labour and capital". Another major event in the life of the Morgnshtern was the International Workers' Olympic Games, organised by the SWSI.

These massive events are today almost completely forgotten. Still, in the 1920s and 1930s, their popularity matched that of the "bourgeois" or "official" Olympic Games (organised by the International Olympic Committee, or IOC). The Second Workers' Olympiad took place in Vienna in 1931, with the participation of 100,000 worker-athletes from 26 countries. By comparison, in the IOC-organised Olympic Games in Los Angeles one year later, only 1408 athletes participated.

The Vienna Workers' Olympiad attracted 250,000 spectators, and it easily surpassed its rival, the IOC Olympic Games, not only in the number of competitors and spectators but also in the many cultural events it included. Unlike the bourgeois Olympic Games, the Workers' Olympiad stressed workers' internationalism, solidarity and peace, and did not restrict entry on the grounds of sporting ability but invited all athletes, encouraging mass participation. The Morgnshtern sent 300 worker-athletes to the Vienna Olympiad, who proudly marched along the avenues of "Red Vienna" displaying their Yiddish banners.

An even more monumental Workers' Olympiad was planned for Barcelona in 1936, in opposition to the Nazi Olympics in Berlin. However, the Barcelona Workers' Games never took place due to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War almost exactly at the same time the Olympiad was scheduled to begin. Thus the Third Workers' Olympic Games were rescheduled for the following year in Antwerp. Despite intensive preparations, the Morgnshtern was banned from participation in this event by the Polish government.

In its early years, the Morgnshtern, while actively opposing competitive or violent sports (in particular boxing and soccer), had simultaneously to deal with their increasing popularity, in Poland as everywhere else. In the 1929 congress of the SWSI, the Morgnshtern proposed a total ban on boxing in all the affiliated federations, and, in parallel, proposed that new rules be set for soccer to diminish its competitiveness and escalating violence. The proposal was that, in soccer competitions, the winning team would be decided not only on the basis of goals scored but also through a system of points rewarding "aesthetic and fair play" and "nice combinations". In this way the increasing brutality of bourgeois soccer would be avoided, and the game would be played according to humanist and socialist principles.

A passionate argument arose in the congress around this issue. The opponents of this proposal thought that soccer in its existing form should be used as a means of bringing the proletarian masses into workers' sport organisations. Besides, they claimed, soccer was so popular among workers that if the workers' clubs did not organise it, they would lose their members to the bourgeois clubs. Similar arguments took place within the Morgnshtern and eventually, as many times before and after, purist ideals were set aside under pressure from below.

The "soccer question" was resolved by the Central Organising Committee of the Morgnshtern in 1930. In the text of the resolution, the leaders of the Morgnshtern rationalised that soccer – with the appropriate approach, organisation and treatment – can help unfold the collective and solidarity senses of the athlete. Soccer greatly captures the interest of the young workers and it is possible to use it to draw the great mass of young workers into the socialist movement.

Following this precedent, other competitive sports were gradually incorporated into Morgnshtern activities, including ping-pong, handball, basketball, volleyball and even boxing. To be sure, regardless of these changes, the non-competitive activities always attracted the participation of larger numbers of people. But Morgnshtern competitive sports teams tended more and more to participate in the general leagues in Poland. Some of these teams reached remarkable achievements, for example, a Morgnshtern member was part of the Polish national team in the ping-pong World Championship in London in 1938.

By the early 1930s there were several Morgnshtern soccer teams in the Warsaw area alone, some representing different Jewish workers' unions. In 1929 the Bundist daily Naye Folkstsaitung sponsored the soccer tournament among the various Morgnshtern teams, offering as a prize the Naye Folkstsaitung Trophy: a bronze sculpture of a worker by a famous Polish sculptor. The winner of the tournament was the Czarny, the soccer team of the union of commerce employees. Two thousand people came to see this tournament. The Bundist press covered each game using the enthusiastic style that had become typical of this kind of reporting (but in Yiddish, of course).

This is how the game between the soccer teams of the Warsaw (Central) Morgnshtern and the Kraft-Morgnshtern was presented: "Kraft played with extraordinary ambition [mit oysergeveynlekher ambitsie] and dominated the field throughout the game. It was possible to see among the players a friendly, collective and cooperative style of play [a khaverish un kolektiv tsuzamenshpiln]; on the other hand, the Morgnshtern played chaotically, without any system, purposelessly kicking the ball around [stam gekopet di pilke arayn] and reaching nowhere. "

Regardless of style and aesthetic, the Warsaw Morgnshtern team won 1:0, because they managed to score a goal in a "suicidal" shot at the last minute of the game, when both teams were exhausted, to the great dismay of our unnamed reporter, who as early as the 1920s preferred controlled and tactical play over players' skills. The reporter of the Arbeter sportler concluded with disappointment that the Kraft deserved at least a draw.

As late as July 1939, a new soccer team was organised in the Warsaw Morgnshtern, and in the following weeks it played several friendly games with other Morgnshtern teams from Warsaw and Vilna. The team showed great promise. On August 8, 1939, it won two games against the older and strongest Morgnshtern teams, Czarny and Veker. A month later, Poland was under Nazi occupation. The Morgnshtern membership would share the fate of the rest of Polish Jewry.

[At the time of writing Roni Gechtman was a doctoral candidate in the history department at New York University. He grew up in Argentina, studied at Hebrew University in Jerusalem and lives in Vancouver, B.C.]

More on the forgotten legacy of workers’ Olympics

By Terry Bell

August 19, 2012

In this week of Women’s Day in South Africa, the 30th summer Olympiad is coming to an end. Over the past week and more, women and men from all backgrounds have displayed their sporting abilities, watched on television by more than a billion people around the world.

But it was not always like that — and not only in terms of television viewing or even the number of participants or spectators. These “modern Olympics” started out as an elitist and exclusively male preserve.

And, once again, as these Games come to an end, they are shrouded in some very modern myths that ignore the real origins of the Olympics — and fail to give credit where credit is due. Much of the credit for the fact that women now compete and that men and women from every background are generally included on the basis of ability alone, goes to the labour movement, mainly in Europe, but also in the United States.

It is a history that has largely been hidden and has no place in the grand commercial circus that is now the Olympics, and has been so since the end of World War II. But, courtesy of historians such as Robert Wheeler of the United States, we have access to this history.

More than 30 years ago, Wheeler unearthed and published much of the background to international “worker sports”, a history that remains neglected and largely forgotten. Unsurprisingly, because these sporting events not only included women, they also often openly rejected the competitive and elitist ethos of the official Olympic movement that got formally underway with the first “modern” Games in Athens in 1896.

Non-competitive hiking, cycling and team sports such as soccer and, in the US, baseball, tended to be the chosen activities in the early years as the labour movement won concessions on working hours and six and seven-days-a-week work. It was only after World War I that individually competitive sport became generally accepted in the worker movement.

And it was a movement that involved millions of women and men. By 1929, for example, the Workers’Cycling Association in Germany had 320 000 members and owned its own bicycle factory. It was affiliated to the main sports federation, ATUS, that boasted more than 1.2 million members.

Throughout, the stress in the worker sports movement was on building unity across national boundaries, to downplay competitiveness and to demand equal rights for all. This was in direct contrast to what is now called the “modern Olympics”.

This concept of a modern Games was based on a romantic notion of ancient Greek competitions dreamed up by a wealthy French nobleman, Baron Pierre de Coubertin. De Coubertin saw such exhibitions of prowess to be by “heroes” and his model for such events was those staged for boys and old boys of elite British private schools such as Rugby and Eton.

His vision of Olympic Games was a way of uniting what he perceived to be the cultured elite of the world across national boundaries, perhaps as a substitute for war, but also as a preparation for conflict. There was also stress on the fact that all competitors should be amateurs. Professionals — those paid to compete — were clearly unsuitable and this effectively excluded working men who could not afford, especially given low pay and long hours, to train to sufficient standard.

The original modern Olympics were, therefore, designed to be exclusive on the basis of class and gender. But to celebrate the common bond of this elite band of competing athletes, an Olympic anthem was composed and was played to celebrate every win by whichever competitor.

This genuflection to internationalism disappeared in 1936 when ultra-nationalist Nazi Germany staged the Olympics in Berlin. One of the legends of those Games is how Adolf Hitler got his comeuppance when an Afro-American, Jesse Owens, won golds against the “Aryan” champions.

Owens did indeed cause Hitler to storm out of the stadium, but the German dictator’s legacy lives on, not only in that national songs replaced the Olympic anthem, but also in the much lauded torch relay and the lighting of the Olympic flame. The Nazis introduced these rituals to symbolise cleansing fire, burning out the filth of the world.

The torch, the flame and the national anthems have survived, as have memories about the 1936 official Olympiad. However, a year later, in August, 1937, there was another Olympiad, this time in Antwerp, Belgium about which few people have heard.

Yet there were more than 50 000 men and women from 15 countries who took part in this, the last of the “Workers’ Olympics”. As fascism swept through Europe, the repression came down especially heavily on trade unionists and socialists of various stripes who were at the centre of the worker sports movement.

This was already evident in Antwerp because, at the previous “Workers’ Olympics” in Vienna, Austria, in 1931, there were an estimated 100 000 participants from 26 countries. They still promoted the slogan of the first such Games, staged in Prague in 1921: No More War!

The Prague Games also included athletes from “enemy states” who were excluded by the official movement. But, by 1939 and the outbreak of World War II, the no war slogan had a hollow ring and the dream of peace and unity was shattered.

However, the egalitarian principles these largely forgotten sportspeople fought for had a global impact, at least in part. After World War II, gender discrimination became unacceptable, as did the insistence on amateurism, so opening the way for talented athletes from other than wealthy backgrounds.

Ironically, the acceptance of professional sportsmen and women in the Olympics was largely the work of a Spanish nobleman and fascist, Juan Antonio Samaranch. A member of General Francisco Franco’s Falange, he headed the International Olympic Committee for 21 years until 2001.

Money is now the main determining factor. Better funding means a better chance on the medals table; and the egalitarian ideal is still a long way off. For example, South Africa’s total investment in all Olympic sports over the past four years was equal to what Britain put into the minority sport of badminton.