The limits to growth: ecosocialism or barbarism

By Alberto Garzón Espinosa, Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal reposted from La-U

Abstract: This year marks the 50th anniversary of the publication of The Limits to Growth, a report warning of the serious ecological consequences of maintaining the trajectory followed by the economic activity at global level. Nonetheless, half a century later, the situation has simply got worse in terms of environmental pressure and impact, while the ideologies and practices built up around the fetish of economic growth have continued to expand. The scientific community warns that time is running out and the only way of avoiding environmental collapse, with its catastrophic consequences especially for the most vulnerable social sectors, is to scale economic activity down to the level compatible with the planetary boundaries. Some international institutions and various national governments have approved programmes and policies to achieve these goals, with meagre results so far, while alarm is growing as to the possibility of a reactionary, eco-fascist solution to the eco-social crisis. In this article, we assess the current position and review how the production and consumption model lies behind ecological breakdowns and why the only democratic political solution to the eco-social crisis is the eco-socialist project.

Introduction

It’s now 50 years since the scientist Professor Donella Meadows led publication of the report The Limits to Growth, which aimed to analyse the physical impact of economic growth patterns on the planet. A computer model was used for that assessment, which looked amongst other things at the effect of economic exploitation on soils, the exhaustion of non-renewable resources such as minerals and the resulting climate distortions. Various scenarios were put forward, the worst case being that, if no action were taken to correct the trajectory followed at the time, industrial society would collapse in the mid-21st century.

That report became an international reference point and highlighted the ecological consequences of the dynamics of growth which had until then been seen as positive. The scientific team’s model, together with its findings, was nevertheless fiercely contested by economists (Solow, 1973).

Economic growth is indeed habitually seen as something desirable, limited in space and time and even as a reflection of a process of natural evolution of societies. The very notion of economic growth is intrinsically connected with the social notion of progress, both of which arise from the Enlightenment and have been victims of forced, equivocal analogies with the natural sciences, particularly based on Darwinist theory (Nisbet, 1980). In short, we have firmly internalized and naturalized the notion of economic growth.

Meadows herself maintained, 30 years later (Meadows et al., 2006), that economic growth should be understood as a tool and not as an end in itself, so that it was necessary to question the rationale of such growth, who would benefit from it and whether there were sources and sinks on the planet to make it possible. This had similarities with what the economist Simon Kuznets had suggested when he designed the GDP indicator and put it forward to the United States Congress. According to Kuznets (Gadrey, 2004), it should not be inferred that this indicator, which measures the monetary value of production, could also be an expression of social well-being. More and more voices have been raised since then, warning that GDP is not a good tool for measuring human development and social well-being (Raworth, K., 2018).

The main problem underlying conventional economics is its reliance on a conceptualization of the economy which deliberately ignores the physical context of which it is necessarily part, as well as the most elementary laws of physics. This means working on the assumption that resources and energy are unlimited, without even considering the fallout of the activity or the planet’s limited carrying capacity. In view of the hegemonic nature of economic thought insofar as it is capable of moulding the framework of social thought, this is crucially important, because it makes finding effective solutions to the eco-social crisis virtually impossible.

Defective economic models

Economic growth can be seen as the result of greater production capacity on the part of a particular society. To simplify, this means that a society which produces a larger quantity of product than it did in the previous year is said to have grown economically by an amount equal to the difference between the two levels of output. In this way, a country which produces 10 units of food in a particular year and produces 12 units of food the following year is said to have experienced a 20% growth in food units. These two new food units are considered as economic surplus. The systematic build-up of economic surpluses lies behind the development of societies, inasmuch as historically it has enabled societies to become more complex (Cesaratto, 2020).

Capitalism is an economic system which emerged around five centuries ago and introduced a series of incentives, through competition, to discipline companies and force them to grow in each period, as well as to reinvest profits in order to raise their production capacity to a higher level, in addition to awarding a growing share of those profits to the people who supplied the capital. In this way, under capitalism the whole entrepreneurial fabric is pushed towards boosting its production capacity. This is what, under particular institutional arrangements, has driven the spectacular increase in economic activity, infrastructure and, finally, the living standards of people over the past two hundred years.

The historical reality of capitalism has, however, demonstrated that the process of economic growth is neither constant nor spared from serious upheavals (leading to phenomena such as unemployment and lack of paid work for large sectors of the society). Economists have also devoted themselves to the task of untangling the difficulties of economic growth for more than two hundred years. Most of them, however, have used a set of theoretical instruments blind to the ecological issue, i.e. the ecological prerequisites for economic growth and the ecological consequences of that growth.

Classical economists, the founders of Political Economy as a discipline, have nevertheless undoubtedly been aware of some of what we might call the social metabolism, i.e. the relationship between nature and the economy (Haberl et al, 2016; González de Molina, M., 2014). The physiocratic school, the predecessor of the above, whose principal exponent was François Quesnay, had already interpreted the economic question in the 18th century on the basis of agrarian flows and concluded that any surplus is possible thanks to the gifts given to us by nature. David Ricardo, on the other hand, was aware of differing soil fertility and put together a theory of decreasing land yields which led him to think that capitalism could not grow indefinitely. Reverend Thomas Malthus introduced his now famous thesis on population growth as a constraint on economic growth. And Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels considered that capitalism would come up against limits to its own development due to the downward trend of the rate of return, although all of this fell within an essentially teleological philosophy of history according to which the whole system would inevitably advance phase by phase until it culminated in communism (Garzón, 2017). A particular remark should, however, be made in the case of Marx, since research over the last few decades has shown that Marx was also a thinker extremely interested in the scientific advances of his time and that he himself accorded considerable importance to the concept of social metabolism (Burkett, 2006; Foster, 2020; Saito, 2022).

In the 20th century, economic thinking, in striving to make the discipline more scientific, moved even further away from the physical and even social conditions under which any economy must necessarily operate. Neoclassical thought, as reformulated by Walras, Marshall & Jevons, amongst others, permeated economic science as a whole and led to a break with the previous Political Economy, giving rise to notions of production and wealth completely disconnected from a natural base (Naredo, 2015). Meanwhile, the search for theoretical explanations of economic growth and its possible failures continued with the economists Harrod and Domar, who developed a model which concluded that economic growth was fundamentally unstable and that meeting the conditions for stability was extremely complicated (Harrod, 1939; Sen, 1970). That Keynesian-inspired model provoked a response from neoclassical economists such as Robert Solow and Swan, who laid the foundations for the paradigm of economic growth and whose models are still being studied as a priority in every economics faculty around the world. These are the models which, in the end, define to a large extent economists’ scope of thought.

The cornerstone of every model of economic growth is the aggregate production function. This function represents the economic production process and, in its most basic formulation, only involves capital and labour, while resources and energy are always considered as fully available. In this way, capital and labour are consolidated as the only production resources which, together, generate the surplus of an economy. This surplus, in its turn, makes up the amount to be distributed between wages and profits.

This is the root of a large proportion of policy discussions around accumulation and distribution in capitalist societies. Ethical and political issues as important as the level of wages or profits or, even more, their relative share of income, arise from the implicit question concerning the effects of those changes on economic growth. Each model belongs to a distinct school of thought due to its specific configuration, determined by different starting assumptions. In general, neoclassical models consider that restrictions on growth come from the supply side, so they suggest that profits must be increased to encourage accumulation, while post-Keynesian models focus on restrictions from the demand side and usually suggest changes in the distribution of income and increases in wages (or public expenditure) to support demand. The large majority of current discussions of economic policy fall within this perspective. Nevertheless, the paradigm is always shared, and the debate really turns on ways to maximize economic growth.

Students of economics are often surprised, when studying these models, especially the most basic ones, that there is apparently no possibility of unlimited growth existing. For example, Solow’s model establishes that the production factors, capital and labour, have decreasing returns, which supposes that each additional unit provides an ever-smaller quantity of product. In its dynamics, the model tends towards a stationary state where there is no economic growth. Nevertheless, when technical progress, in whichever possible formulation, is incorporated in these basic models, it is then possible for potentially unlimited growth to exist. This is what happens with the AK growth or endogenous growth models, as well as all models incorporating growing returns in the aggregate production function (Acemoglu, 2009; Romer, 2000). In the end, students soon learn that unlimited economic growth is technically possible thanks to technology and, in the case of certain heterodox models drawing inspiration from Allyn Young, Gunnar Myrdal, Nicholas Kaldor and Anthony Thirlwall, also the central role played by the industrial sector (Blecker & Setterfield, 2019).

This brief review of the relationship between economic models and public policy should make it clear above all that economists, past and present, generally tend to think within analytical and conceptual frameworks defined on the basis of the search for maximum economic growth. The responses given are dependent on the use of a set of theoretical instruments which, whether explicitly or otherwise, is limited by its own deficiencies. Bearing in mind the fundamental role played by economists in framing public debate, disseminating their own ideas, influencing the decisions of public institutions or, as in the case of central banks, directly holding absolute control of particular levers of power, it is more than ever necessary to find out the source of these limitations.

What all these trends and schools of thought have mostly ignored, both in their methodological foundations and in their policy proposals, is the connection between productive activity per se and the natural foundations on which it sits and which it cannot do without. In other words, there is absolutely no vision of the social metabolism, which entails starting from a world view where the economy is seen as a subsystem of the biosphere and not the other way around. This lack, wholly illegitimate in our times, relates to the physical aspects of the economic process, the use of energy and natural resources and the ecological pressures and impacts of the production process.

Natural resources and energy

The economist Georgescu-Rogen (2007) was one of the first to warn of the serious deficiencies in traditional ways of thinking about the economy. In particular, he highlighted the gap in economic models regarding the consumption of energy and materials. Both components restrict the possibilities of economic growth in ways that economics had ignored until just a few years ago[1]. In fact, planet Earth is a closed system of materials so that, aside from the very exceptional arrival of a meteorite or the removal of a human artefact, neither of which are significant in quantitative terms, the mass of materials is always the same. In the case of energy, planet Earth is an open system inasmuch as we receive energy flows from solar radiation, but even then, the laws of physics impose limits on energy use.

These days, we accept that most of the products we use in our daily lives are made from a combination of energy, water, and materials and also that, for the production process, we need energy sources too in order to extract and process those materials. We also know that they come from the geochemical cycles of Earth and most originated millions of years ago due to plate tectonics, which not only generated but also distributed resources geographically across the planet, although obviously not uniformly (Craig et al., 2012). For this reason, some regions of the planet are rich in petroleum and natural gas, while others are rich in other minerals, all of which have clearly shaped the historical development of societies and, of course, wars over resources as well. And we also know that a large part of these resources is non-renewable, i.e. they exist in fixed quantities and their natural regeneration occurs over a timeframe inaccessible to human beings. Furthermore, any resources which do renew cyclically are also limited by their own pace of regeneration.

Moreover, every human process involves use of a series of energy sources governed by the laws of physics, particularly the laws of thermodynamics. The second principle of thermodynamics establishes that the quality of energy usable by human beings is decreasing and that, in converting energy (for example, converting the energy deriving from solar radiation to photosynthesis or generating electricity through photovoltaic panels), it is not possible to maintain 100% of the available energy. Much of the energy is dissipated as heat, so that conversion presupposes the transformation of high-quality, low-entropy energy, such as carbon, into low-quality, high-entropy energy such as heat. The history of technological development is the history of a constant struggle to improve the energy efficiency of such conversions (Smil, 2021).

Flows of materials and flows of energy can be understood as two distinct aspects of the same process. In fact, a continuous flow of materials is only possible if there is a continuous flow of energy at the same time. In addition, these two restrictions on economic growth interact in very diverse ways and the ecological pressure and impact of productive activity also show up in the alteration of geochemical cycles.

It is usual, however, to differentiate between pressure and impacts deriving from productive activity. On the one hand, productive activity exerts pressure on the environment, for instance through the emission of carbon dioxide resulting from burning fossil fuels. On the other, the impact of productive activity on the environment shows up in phenomena such as climate change, i.e. global warming resulting from the sustained build-up over time of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Over the last few decades, the availability of information has significantly improved and many indicators have been put together with a view to measuring the level of pressure and impacts exerted by the production and consumption model on the natural environment.

The planetary boundaries

There is no doubt that human beings have lived on Earth for at least two hundred thousand years, although most of the time they did so in hunter-gatherer social groups. The end of the last ice age, which occurred some twenty thousand years ago, gave way to an extraordinarily warm climate which, in its turn, enabled human beings to develop new economic and social practices, such as agriculture (developed some 12,000 years ago). Scientists have agreed to call this warm era the Holocene, in which current civilizations developed.

Since the Industrial Revolution, the use of resources and energy by humanity has, however, increased to a marked degree. Many studies on environmental history describe these transformations very well (McNeil, 2003). This intensive use of resources and energy, especially energy from fossil fuels, has brought about a rise in living standards and with it an increase in population throughout the world. These trends have speeded up, especially since the mid 20th century, as can be seen in the following graphs. The period beginning at that time has been called the Great Acceleration (Steffen, 2020).

In more general terms, the scientists Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stormer coined the term Anthropocene more than two decades ago to refer to the change from one geological epoch to another, meaning that these days, as a consequence of the development of the global economic system, humanity mobilizes more land and sediments than any other natural process. Other authors use the expression Capitalocene to point out what is ultimately responsible for all of these transformations: the type of economic system (Foster, 2020).

Furthermore, in 2009, a group of scientists developed the «planetary boundaries» framework with reference to the main ecological thresholds which, if lowered, could entail significant planet-wide alterations in natural cycles (Rockström et al., 2009). The main virtue of this new framework is that it extends the range of attention beyond climate change, much more generally known, to encompass other environmental impacts such as the loss of biodiversity, acidification of oceans or contamination due to excess nitrates or plastics. Nine bio-geological phenomena were identified which, if specific limits were exceeded, would trigger one-way processes threatening life itself. This framework is based on the existence of a safe space, with boundaries determined by the specific bio-geological parameters of the Holocene, within which human beings could live with a degree of security. At the moment, five of the critical thresholds for life are thought to have been passed, highlighting the urgency of a forceful response to these imbalances.

One of the main problems with the planetary boundaries’ framework, however, is that it looks at social metabolism in an essentially technical way. If the analysis is not broadened, the framework seems to place responsibility on abstract notions such as «humanity» or «the human being», when it is obvious that neither the causes nor the consequences of the ecological impact are symmetrically distributed either across the class structure or between the different geographical regions. There is in fact no global ecological crisis which means the same for all human beings (Brand et al., 2021). Therefore it is much more appropriate to talk of an eco-social crisis, because this helps to highlight the importance of socio-political relationships when assessing environmental degradation processes and seeking solutions.

Some authors, such as the English economist Kate Raworth (2018), have added a social dimension to the sphere of planetary boundaries. The result, popularly known as the circular economy, points out the need for people in modern societies to live above the «social floor » (decent minimum living standards) and below the planet’s biophysical limits (ecological ceiling), thereby establishing a safe, fair space for humanity. This contribution is useful in that it allows for the incorporation of aspects such as inequality, poverty, or decent work together with the strictly biophysical limits.

The impact of consumption

Since the publication of Limits to Growth, the close link between economic growth and the heavy ecological pressure and impacts threatening life on the planet has been generally acknowledged. For this reason, the United Nations developed the Sustainable Development Goals. Target 8.4, for example, is to «improve progressively, through 2030, global resource efficiency in consumption and production and endeavour to decouple economic growth from environmental degradation». The European Union also adopted this agenda and has, since then, approved a large number of standards designed to achieve those goals, as has Spain.

The scientific work built up over the last few decades has resulted in the proliferation of indicators to measure the impact of economic activity on the planet and this has facilitated the pursuit of these commitments. The general public, for example, have become familiar with indicators measuring carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and are even aware of the impact of their Carbon Footprint on their daily life and consumption decisions. Nonetheless, as we have already noted, environmental impacts go beyond climate change and also require other indicators.

One of the most advanced approaches in this regard has to do with the flow of materials involved in the production and consumption model. The extraction and processing of resources is responsible for approximately 50% of greenhouse gas emissions and more than 90% of the loss of biodiversity on the planet (UNEP, 2019). And it has been proved that there is a direct, close relationship between the consumption of materials and economic growth. This is basically the result of the impulse to consume.

Consumption is the main driver of global economic impact, far ahead of other demographic factors such as age, household size, cultural capital, or housing structure (Wiedmann et al., 2020). It must be stressed that consumption is required to close the capital cycle, i.e. for production to be sold and economic growth to exist. Consumption and production are, in this sense, two sides of the same coin (Harvey, 2007). After all, under capitalism, production is geared towards economic gain – rather than satisfaction of human needs – so that economic actors are disciplined to ensure that their production is sold, through consumption, and the profits are reinvested in greater production, i.e. for growth. If aggregate demand were insufficient to cover production and stocks in a particular period, the system would be facing a crisis. For this reason, under capitalism, the incessant consumption spiral mirrors the incessant production spiral.

It should be remembered that any product coming onto the market carries with it a baggage of both visible and invisible resources, meaning that any product involves use of the materials it is made of, but also the materials necessarily consumed in manufacturing that product. For example, a single smartphone is made up of dozens of mineral substances such as lithium, aluminium, silicon, copper, and nickel, but its production also relies on consumption of huge amounts of water – according to some estimates, twelve thousand litres of water per unit (Friends of the Earth, 2015) – and other materials, in addition to generating waste during the production process and waste due to its early obsolescence. With economic globalization and the development of global value chains, the material and technological complexity of products has increased and with it the commercial exchange of raw and other materials and waste between countries. This applies not only to the consumption of electronic products but also to food products – as the world agri-food system is responsible for 34% of greenhouse gas emissions (Crippa et al., 2021) – and to the global tourism industry – the cause in its turn of 8% of greenhouse gas emissions (Lenzen et al., 2018). All our daily activity is tied to a particular level of resource and energy consumption which exerts pressure on and impacts the natural environment.

The extraction of material resources has in fact been stepped up throughout the world in recent decades, as is clear from the following graph going back to the beginnings of the last century (Krausmann, 2018). It can be seen, moreover, that there has been incredible growth since the second half of the last century, a good description of the Great Acceleration period. In 2017 for example, the average person consumed 65% more resources than in 1970 (UNEP, 2019).

The Domestic Extraction indicator is generally used to find out the precise impact of the production and consumption model on the use of natural resources in a particular territory. It measures natural resource use within the borders of a country. The drawback of this procedure, however, is that it does not record the impact of international trade and can lead to the belief that certain countries, traditionally net importers of products, are improving their indicators of the impact of resource use when this result might, for example, reflect the fact that they have relocated material-intensive industries. Another indicator used is Domestic Material Consumption, which does take account of international trade, but only adds the physical weight of the apparent consumption of imported and exported goods. This means that no account is taken of the quantity of resources used to produce the imported and exported goods. To solve this problem, a much more accurate indicator has been developed. Known as the Material Footprint, it describes the consumption of both domestic natural resources and imported goods, also including the resources used in producing those internationally traded goods (Wiedmann et al., 2015).

The Material Footprint is therefore the best available indicator to assess the impact of the production and consumption model on resource use. At aggregate level, the Material Footprint necessarily coincides with Material Extraction – due to the fact that imports and exports cancel each other out at global level – which means that the growth of the Material Footprint has also been spectacular over the last 50 years. It has nevertheless been asymmetric, because not all regions are equally responsible for this growth in natural resource use. If we look at per capita resource use, we can see that North America – mainly due to the United States – is clearly in the lead with consumption of 30 tonnes per person in 2019. This is 1.5 times the consumption recorded in Europe and up to 7 times higher than the figure for Africa.

This is somewhat similar to what happens with greenhouse gas emissions at global level, given that the so-called Global North has been responsible for 92% of cumulative carbon dioxide emissions since 1850. The United States alone accounts for 40% of those emissions, while the countries making up the current European Union are responsible for 29% (Hickel, 2020).

When we begin to look at the situation within different countries, we find that the upper income strata are the largest consumers of resources. As we have said, societies under capitalism are structured into classes and, insofar as resource consumption is linked to income, it is to be expected that the greatest ecological impact will come from the wealthiest social groups. Moreover, some research has shown that, at global level, the richest 10% are responsible for between 25% and 43% of carbon dioxide emissions (Bruckner et al., 2022), so it is clear that the ecological impact is driven by the richest citizens of each country.

In the case of Spain, the country’s material footprint has grown in the last 50 years, although with two clearly differentiated sub-periods. Until the financial crisis, the trend was upward, speeding up at the beginning of the century with the property boom, but the subsequent downward trend has continued ever since. This pattern points to possible dematerialization, i.e. less resource consumption per year. This is due to a large extent to the economic crisis, but it may also reflect changes in the production structure – towards less resource-intensive sectors – or an increase in technological efficiency.

The problem with the Material Footprint, as well as all the other previously mentioned indicators, is that they only reflect the consumption of materials. To take account of other types of impacts, the European Commission has developed a new methodology, based on the full product life-cycle, which has led to the construction of two new indicators: the Domestic Footprint and the Consumption Footprint (Sala, 2019).

The Domestic Footprint reflects the ecological impact (not of resources alone, but also a further fifteen aspects), taking account solely of what is produced within the country. On the other hand, as the Consumption Footprint also covers the effect of international trade, it incorporates the impact of all the goods produced abroad but consumed in our country (deducting the impacts of what we produce here for consumption in other countries). In the case of the European Union, the data show that in the period between 2005 and 2014 there was a relative reduction in environmental impacts, although with very different indicators from one country to another. The most significant environmental impact was felt in countries which are traditionally importers of fossil fuels, meat, minerals and manufactured products, resulting in a higher Consumption Footprint (Sanyé-Mengual, 2019). When we analyse the performance of both indicators for Spain, we see that they have moved in opposite directions in the last few years. Regarding the domestic ecological impact, there has been an improvement over the last decade. Despite this, when we look at the ecological impact of consumption as a whole – including imported goods – the economic recovery since 2013 also meant a clear increase in the ecological impact which has continued ever since.

All in all, at this point and 50 years after the publication of Limits to Growth, the debate no longer centres on whether economic growth is associated with pressure and impact on the natural environment, given that there is an overwhelming consensus in this regard, but whether it is possible to decouple the two phenomena sufficiently quickly to prevent the social metabolism from reaching the point of no return as regards the planetary boundaries. This is, precisely, the debate between «green growth or degrowth».

Degrowth and technological efficiency

According to the dominant view in international institutions such as the United Nations or European Union, to avoid the worst ecological scenarios the aim must be to reconcile economic growth – which is considered essential to social well-being – with use of resources and energy remaining within the planetary boundaries. This would be possible if there were a decoupling of some variable used to measure economic activity (normally GDP) from the variables used to measure ecological pressures and impacts (such as carbon dioxide emissions, use of material resources, etc.).

When the ecological pressure and impact variables grow at a slower rate than GDP, a relative decoupling is said to have occurred, whereas if GDP grows but the pressure and impact variables decrease, an absolute decoupling is said to have occurred. To achieve these objectives, great hope has been placed in technological efficiency, seen as the set of technologies which, applied to the production process, enable the latter to consume fewer resources and less energy per unit of product in monetary value. This is the technological optimism on which the whole narrative of green growth is based.

Most of the analyses carried out have, however, concluded that in general no decoupling between economic activity and environmental pressure and impact is happening and, furthermore, is unlikely to happen at any point (Parrique et al., 2019). In most cases, no kind of decoupling is taking place with regard to consumption of materials, energy consumption, water use, greenhouse gas emissions or loss of biodiversity and, where any study has found some evidence of decoupling, it has been based on local analyses, restricted to specific countries or regions, for short periods of time – during a crisis, for example – or on an insufficient scale to tackle the ecological challenges (Parrique et al., 2019; Haberl, 2020).

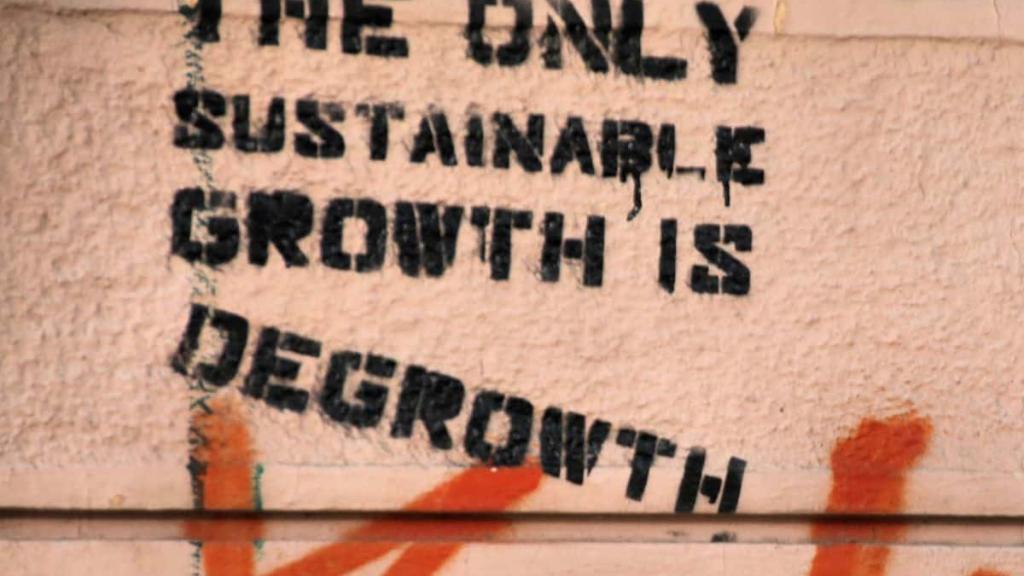

It is obvious that strategies to increase technological efficiency must be complemented with sufficiency strategies, i.e. with a reduction in the material scale of production and consumption in many sectors so that economic activity can fit within the planetary boundaries. This is where the proposals for degrowth have emerged most forcefully (Hickel, 2021). Degrowth began as a political and social movement and should not be understood either as an economic concept or as a consistently structured theory, but as a broad, heterogeneous stream of thinkers and proposals seeking to ensure development of the global economy within the planet’s biophysical limits (Demaria, F. et al, 2018). Quite simply, degrowth should be understood as a criticism of the theory of decoupling and green growth and as an affirmation of the need to reduce the pressure of human beings and their economic model on the ecosystems and natural environment without betting everything on technological promises.

Eco-socialist strategies versus barbarism

Fifty years since The Limits to Growth, is more research needed to confirm that there is a serious eco-social crisis? The answer is undoubtedly no. We are now fully aware that the production and consumption model is causing pressure and impacts on the natural environment to such an extent that life itself is threatened. What is lacking, however, is the political will to take decisions equal to that challenge, as the institutional policies followed to date have proven clearly insufficient. Despite the speeches and rhetoric from the governments of the most developed countries, the commitment in the Paris Agreement not to raise the global temperature by more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels is currently undeliverable. On the contrary, according to the research of the United Nations IPCC, the world is on a path towards a catastrophic rise of 2.7°C by the end of the century (IPCC, 2021).

This being the case, the key task of democratic societies should be to build resilient communities capable of prioritizing the well-being of their members without permanently damaging the natural environment which sustains them, as well as to prevent escalation of the social conflicts and wars increasingly linked to the eco-social crisis (Pirgmaier & Steinberger, 2019; Belcher et al., 2019). As we have seen, however, achieving this eco-social-political objective necessarily entails scaling down the material dimension of the economy to bring it within the planetary boundaries, with far-reaching political, social, and economic implications.

To begin with, a complete reframing of the consumption dimension is needed. Firstly, although it is true that consumers cannot take decisions concerning the supply side, such as the location of major production centres, they do have plenty of room to influence decisions on the demand side. It is not easy to take advantage of this capacity, because capital is a social relationship and, therefore, far more than a production and consumption model: it is a way of life. This means looking at the values and principles of capitalist consumption, which goes beyond human needs and the planetary boundaries, the ways such practices are socially reproduced and what potential centres of resistance could be generated (Pirgmaier, 2020). Secondly, when it comes to the necessary achievement of ecologically sustainable consumption, the starting point must be that the market is incapable of distinguishing between goods meeting basic needs and goods of a luxury nature (Gough, 2017). Therefore, we need to move in the direction of an approach based on gearing the economy towards the satisfaction of human needs.

Approaches of this type inspired by Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum and their influence on the United Nations Development Programme, together with the contributions of Max-Neef or Ian Gough (Álvarez Cantalapiedra, 2013), should replace the dominant paradigm of economic growth. The utilitarian tradition in economics maintains that there is a positive, infinite relationship between income growth and happiness/well-being. Specialist literature has nevertheless argued in favour of the existence of the «Easterlin Paradox», according to which increased income does not, beyond a certain point, result in increased individual happiness (Easterlin, 1974).

Regarding production and distribution, if this adaptation process is to be socially just as well, there must also be a significant flow of redistribution between social classes and a general reorientation of production towards activities which may be low intensity when it comes to ecological pressure and impact but instead have a high component of satisfaction of human needs. To this end, programmes such as guaranteed work can be useful while providing a tool to combat unemployment (Garzón & Guaman, 2015).

Moreover, democracy will only survive the coming social tensions if it can put itself forward as a complete programme of positive safeguards, meaning that it must be in the republican tradition with an underlying positive conception of the notion of freedom (Ferrajoli, 2011; Garzón, 2014). Consequently, consolidating and ring-fencing public services such as health, education, housing and pensions, amongst others, is an essential part of a not only ecologically sustainable but also socially just society.

The alternative policies outlined above must nevertheless start from a concrete analysis of concrete reality. A large part of scientific research concerning the eco-social crisis has given us ever more accurate information on what is happening in the social metabolism. It is much harder, however, to find the reasons why this is happening, which specific actors are responsible and which obstacles stand in the way of changing direction.

Firstly, it is unusual to find research which, along with technical analysis of the eco-social crisis, also provides a specific analysis of how power operates. When all is said and done, power is a social relationship which inevitably defines the limits of what it is possible, at the same time as the possibilities of implementing policies which may look simple on paper are moved closer or further away. For example, although the need to reduce global meat consumption in order to combat climate change effectively has been sufficiently documented, it is not easy to find any analysis which also incorporates thinking about how to put such notions into practice. In other words, analysis of the political ecosystem extending to power in its various guises (business lobbies, major production companies, production fabric, communications media, political and trade union alliances, or the State itself as a whole) is lacking (Fuchs et al., 2015).

Secondly, if power is missing from much of current thinking, the absence of thinking about the ultimate causes of the eco-social crisis is even more marked. It is true that the drivers of environmental destruction are, as we have said, pressure and impacts such as disproportionate use of resources and energy, greenhouse gas emissions and so on. But there is no use in reaching that point if no link is made with the ultimate, systemic causes which explain why this catastrophic process is still going on. In the end, without an understanding of how capital operates and how it pushes all actors (from the working class through to major companies) to achieve economic growth ad nauseam, the analysis will be lame. For this reason, if any analysis of the relationship between economics or society and environment truly wishes to go beyond the frontiers of academia and, consequently, genuinely seeks to transform the material reality it is examining, it must be capable of drawing on dynamic approaches to the study of the system which currently links together economic, social and environmental aspects, i.e. capitalism. The central contradiction of this economic system, as we have already remarked, is that it functions and operates as if it were disconnected from the natural base on which it necessarily stands. And as suggested by Marx, the main problem with capitalism is its huge success in achieving its objectives. We now know that life simply cannot bear the costs associated with this success.

The central ideological opponent of capitalism has historically been socialism, a socio-political movement without which even modern democracy itself could not be understood. But as it arose in the 19th century, socialism has also long been characterized by widespread ignorance of environmental pressures and impacts. Furthermore, most of the theoretical output concerning the economic measures to be taken in defence of the working class is blind to its ecological consequences. Even the most recent theoretical work. As we have already pointed out, the influence of the traditional way of thinking about the economy has seriously contaminated the thinking of socialists and the left in general, as can be seen currently in those uncritically productivist approaches from which economic policy proposals and measures classed as leftist are derived. Some researchers even speak of the role played by these authors as protagonists of a «passive revolution» – a concept Gramsci used to describe the ability of the dominant classes to co-opt the leaders of the subordinate classes (Spash, 2020). These policies, however, are not just the result of a specific conception of the world but at the same time serve to educate entire generations of opponents of capitalism in a particular political culture.

This blind spot of socialism is not the only dangerous legacy from the past. It should be remembered that the type of society we presently know, which has seen rapid development essentially over the last two hundred years, has come about as a result of intensive use of natural resources, especially fossil fuels. The predominant role of fossil fuels can hardly be exaggerated. The whole social architecture we see before us now is due to fossil capital, not just in historical terms but also in the present day. Everything from productive activities through to the layout and design of our cities, not to mention the way of living of working families, is shaped by the dynamics of fossil capital. Serving as an emblematic demonstration is the fact that, when there have been other upheavals in the energy markets, as happened in the 1970s and is happening again now following the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, the whole social system is transformed, from its material through to its ideological dimension. As if it were Achilles’ heel, dependency on fossil capital expresses the fragility of the whole social system, including modern democracy itself – also a child of its time – and that includes cheap energy (Mitchell, T., 2013).

The issue here is obvious. In a world with finite natural resources and fossil fuels reaching or exceeding their respective peaks, the crossroads at which we find ourselves should not be underestimated. We already have before us the first signs that one of the alternatives gaining ground in the face of this eco-social crisis is a new form of fascism, which promotes a type of closed, authoritarian social organization aimed at meeting the needs of select social groups to the detriment of the rest of the population. This type of Weberian social closure, which is characterized by insider/outsider dynamics, has fundamental socio-political implications. A growing proportion of international migratory flows are currently due to climate change and environmental crises and their effects on impoverished countries, while the neo-fascist response to migration brings traditional racism into line with climate denial and a commitment to authoritarian solutions to the eco-social crisis (Malm & Zetkin Collective, 2021). This route can only lead to barbarism. It is not by chance that the growth of the global reactionary wave is happening at the same time as we have the best and most accurate information about the way humankind is running out of time under this economic model. Clearly, it is not sufficient to be right. Currently, some of the social and generational frustrations of our time are being articulated politically through a reactionary solution which seeks to defend «our own» – the native – including lifestyle, against the foreign. An ideological/material retreat of broad social sectors in the face of the fundamental uncertainties of the Anthropocene era. Old scents in new bottles.

Taking up these challenges will not be a matter of simple political prescription. Once again, nor will it be a question of winning arguments. Rather, it will be to do with the ability to put together broad social and political alliances able to prepare the ground for a whole historical and social block to emerge. Local initiatives and global proposals, classical traditions, and new ways of thinking, along with social and institutional action, must play a part in this broad community, in an exercise to build a social fabric feeding on imagery and looking towards a horizon of peace, justice, equality and social rights within the planetary boundaries.

In the past, the idea of an alternative – socialism or barbarism – was popularized by Rosa Luxemburg against the bellicose backdrop of the First World War. The traditional Marxist conception of the time theorized that capitalism was at such an advanced stage of development – in its imperialist phase – that the only thing that could come out of it was international socialist revolution or the destruction of every trace of civilization under the yoke of the war and its consequences. In a way, there were indeed revolutions and a lot of destruction. Not only Europe but the whole world was devastated by two World Wars and totalitarian regimes, while those turbulent times swept away millions of human beings, including Rosa Luxemburg herself, assassinated in 1919 during the Spartacist uprising.

Presently, that alternative is perfectly valid. Human civilization, any civilization, can only build horizons of justice and well-being if it can find a way to do so within the planetary boundaries. Fitting within or readjusting to those boundaries, if we may put it like that, can happen in either an organized or a chaotic manner, the worst-case scenario being ecological collapse. Any of the intermediate scenarios will in any event oblige us to reorganize ourselves through other rules. But we must not forget that the politics striving hardest to prevail in these situations of emergency and collapse is that of authoritarianism, discrimination, inequality, and militarism. It is, once again, barbarism. To avoid it, we must open an alternative road based on other principles and values, democracy, human rights and social justice. This is the route towards eco-socialism. It is therefore a matter of choosing between eco-socialism or barbarism.

Alberto Garzón is an economist, leader of United Left party (Spain) and Minister of Consumption Affairs of Spain’s Government. This article is part of a project of the Party of the European Left.

Note

[1] To be fair, the most recent models incorporate a new productive resource known as natural capital, although with significant limitations deriving from the difficulty in reducing the complexity of ecosystems to a single monetary value.

Bibliography

Acemoglu, D. (2009): Introduction to Modern Economic Growth. Princeton University Press.

Álvarez Cantalapiedra, S. (2013): “Economía Política de las necesidades y caminos (no capitalistas) para su satisfacción sostenible”, Revista de Economía Crítica, 16.

Belcher, O., Bigger, P., Neimark, B., Kennelly, C. (2019): “Hidden carbon cost of the “everywhere war”: Logistics, geopolitical ecology, and the carbon boot-print of the US military, Trans Inst Br Geogr, 2019, 00:1-16.

Blecker, R., Setterfield, M. (2019): Heterodox Macroeconomics. Edward Elgar.

Brand, et al. (2021): “From planetary to societal boundaries: an argument for collectively defined self-limitation”.

Bruckner, B., Hubacek, K., Shan, Y., Zhong, H., Feng, K. (2022): “Impacts of poverty alleviation on national and global carbon emissions”, Nature sustainability

Burkett, P. (2006): Marxism and Ecological Economics. Brill.

Cesaratto, S. (2020): Heterodox Challenges in Economics: Theoretical Issues and the Crisis of the Eurozone. Springer.

Craig, J. R., Vaughan, D. J., Skinner, B., (2012): Recursos de la Tierra y el medio ambiente. Pearson.

Crippa, M., Solazzo, E., Guizzardi, D., Monforti-Ferrario, F., Tubiello, F. N., & Leip, A. J. N. F. (2021): “Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions”. Nature Food, 2(3), 198-209.

Easterlin, R. A. (1974): “Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot? Some Empirical Evidence”. Nations and Households in Economic Growth, pp. 89-125

Ferrajoli, L. (2011): Poderes salvajes. Trotta.

Foster, B.J. (2020): The Robbery of Nature: Capitalism and Ecological Rift. Monthly Review Press.

Friends of the Earth (2015): “The land and water footprints of everyday products”, available at https://catalogue.unccd.int/587_mind-your-step-report-76803.pdf

Fuchs, D., Di Giulio, A., Glaaba, K., Lorekc, S., Maniatesd, M., Princene, T., Røpkef, I. (2015): “Power: the missing element in sustainable consumption and absolute reductions research and action”. Journal of Cleaner Production Vol. 132, pp 298-307.

Gadrey, J. (2004): “What’s wrong with GDP and growth? The need for alternative indicators”, en E. Fullbrook (ed.), A guide to what’s wrong with economics (pp. 262–276). Anthem Press.

Garzón, A. (2014): La Tercera República. Península.

Garzón, A., Guamán, A. (eds.) (2015): El Trabajo Garantizado. Una propuesta necesaria frente al desempleo y la precarización. Akal.

Garzón, A. (2017): Por qué soy comunista. Península.

Georgescu-Roegen, N. (2007): Ensayos bioeconómicos. Antología. Catarata.

González de Molina, M., Toledo, V. M. (2014): The Social Metabolism. A Socio-Ecological Theory of Historical Change. Springer.

Gough, I. (2017): “Recomposing Consumption: Defining Necessities for Sustainable and Equitable Well-Being”, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 375: 1-18.

Haberl, H., Fischer-Kowalski, M., Krausmann, F., Winiwarter, V. (2016): Social Ecology. Society-Nature relations across Time and Space. Springer.

Haberl, H. (2020): “A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part II: synthesizing the insights”, Environmental Research Letters, 15, 065003.

Harrod, R. (1939): “An Essay in Dynamic Theory”, The Economic Journal Vol. 49, No. 193 (Mar., 1939), pp. 14-33.

Harvey, D. (2007): Limits to capital. Verso.

Hickel, J. (2021): Less is more: How Degrowth Will Save the World. Windmill Books.

Hickel, J. (2022): “Quantifying national responsibility for climate breakdown: an equality-based attribution approach for carbon dioxide emissions in excess of the planetary boundary”, Lancet Planet Health, 4: 399-404.

Higgs, K. (2022): “A Brief History of The Limits to Growth Debate”, en Williams, S. J. y Taylor, R. (2022): Sustainability and the New Economics.

IPCC (2021): “Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis”.

Lenzen, M., Sun, Y-Y., Faturay, F., Ting, Y-P., Geschke, A., Malik, A. (2018): “The carbon footprint of global tourism”, en Nature Climate Change, vol. 8, pp. 522-528.

Malm, A., Zetkin Collective (2021): White Skin, Black Fuel: On the Danger of Fossil Fascism, Verso.

McNeil, J.R. (2003): Algo nuevo bajo el sol. Alianza Editorial.

Meadows, D., Randers, J., Meadows, D. (2006): “Limits to Growth. The 30-year update”. Earthscan.

Mitchell, T. (2013): Carbon Democracy, Verso.

Naredo, J. M. (2015): La economía en evolución. Siglo XXI.

Nisbet, R. (1980): Historia de la idea de progreso. Gedisa.

Parrique, T., Barth, J., Briens, F., Kerschner, C., Kraus-Polk, A., Kuokkanen, A., Spangenberg, J.H. (2019): “Decoupling debunked. Evidence and arguments against green growth as a sole strategy for sustainability”.

Pirgmaier, E. & Steinberger, J.K. (2019): “Roots, Riots, and Radical Change – A Road Less Travelled for Ecological Economics”, in Sustainability, 11, 2001.

Pirgmaier, E. (2020): “Consumption corridors, capitalism and social change”, Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 16:1, 274-285.

Raworth, K., (2018): Economía rosquilla. Paidós.

Rockström, J., Steffen, W. L., Noone, K., Persson, A., Stuart Chapin, F. (2009): “Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity”.

Romer, D. (2000): Advanced macroeconomics. McGraw-Hill.

Saito, K. (2022): La naturaleza contra el capital. Bellaterra Edicions.

Sala, S., Beylot, A., Corrado, S., Crenna, E., Sanyé-Mengual, E., Secchi, M. (2019): “Indicators and assessment of the environmental impact of EU consumption. Consumption and Consumer Footprints for assessing and monitoring EU policies with Life Cycle Assessment”, JRC Science for Policy Report.

Sanyé-Mengual, E., Secchi, M., Corrado, S., Beylot, A., Sala, S. (2019): “Assessing the decoupling of economic growth from environmental impacts in the European Union: A consumption-based approach”.

Sen, A. (1970): Growth Economics. Penguin modern economics.

Smil, V. (2021): Energía y civilización. Una historia. Arpa Editores.

Steffen, W. (2022): “The Earth System, the Great Acceleration and the Anthropocene”, in Williams, S. J. y Taylor, R. (2022): Sustainability and the New Economics.

Spash, C.L. (2020): “Apologist for growth: passive revolutionaries in a passive revolution”.

Solow, R. (1973): “Is the End of the World at Hand?”, Challenge, vol. 16. n. 1, pp. 39-50.

UNEP (2019): “Global Resources Outlook 2019. Natural resources for the future we want”.