Marx’s critique of political economy: The logic of the commodity

For all who read Capital for the first time, comprehending the first chapter is never easy. This is not merely because, as Karl Marx remarked, “Beginnings are always difficult in all sciences.”1 It is far more because the audience, and its assumed intellectual background, has changed.

Marx’s critique was developed in the wake of the end of classical German philosophy and the dissolution of Hegelianism. Thus it assumed some acquaintance with the movement from Immanuel Kant to Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Lacking this makes understanding Marx’s treatment of the commodity, both its method and premises, impossible without the aid of other texts.

The purpose of this essay, though, is not to provide yet one more commentary on Marx’s discussion of the value-form of the commodity. Rather it is to provide an overview of the intellectual roots of his approach and explain the dialectical logic of his analysis of the commodity, the very basis of his call for communism.2

Critique and dialectical logic

In 1781 Kant proclaimed the aim of the modern era as a project of critique, with the following words: “Our age is the age of criticism, to which everything must be subjected.”3 He then went on to argue that the “sacredness of religion, and the authority of legislation, are by many regarded as grounds of exemption from the examination of this tribunal. But, if they are exempted, they become the subjects of just suspicion, and cannot lay claim to sincere respect, which reason accords only to that which has stood the test of a free and public examination.”4

Criticism, then, meant an examination by means of reason. However, in the first place, and as the most immediate goal, reason was to be applied to itself. Kant specified that he was giving a “call to reason, again to undertake the most laborious of all tasks — that of self-examination,” and, further, establishing “a tribunal, which may secure it in its well-grounded claims, while it pronounces against all baseless assumptions and pretensions … according to its own eternal and unchangeable laws. This tribunal is nothing less than the Critique of Pure Reason.”5 Therefore his critique “of the faculty of reason” would be the self-critique of reason itself.6

Now to critically examine something by means of reason means to judge, and logically this means to prove something as either necessarily true or untrue. This is precisely why Kant described logic as “the science that contains the formal rules and principles of thought.”7 A self-critique of reason, then, must involve logic itself.8

However, Kant failed to properly carry this out according to his own systematic principle of architectonic.9 Thus Hegel opened his Science of Logic by noting that the “complete transformation which philosophical thought in Germany has undergone” due to Kant’s revolution in philosophy, “had but little influence as yet on the structure of logic.”10 That is, he argued that “the science of logic” also “constitutes metaphysics proper or purely speculative philosophy,” and so his aim was the “reconstruction of logic.”11

In Hegel’s view, both Aristotle and Kant had fallen short of adhering to the rules of logic itself. More exactly, the different forms of thought “which come up for treatment as well as their further modifications are only, as it were, historically taken up; they are not subjected to criticism to determine whether they are in and for themselves true.”12 These forms were therefore merely assumed to be true.

Hence, the “Kantian philosophy did not consider the categories in and for themselves,” nor did it “subject to criticism the forms of the Notion which are the content of ordinary logic; on the contrary, it has adopted a portion of them, namely, the functions of judgement, for the determination of the categories and accepted them as valid presuppositions.”13 The task that remained was thus “to ascertain how far,” the forms of thought, “on their own account … correspond to the truth. A logic that does not perform this task can at most claim the value of a descriptive natural history of the phenomena of thinking just as they occur.”14

This is why, although it was “an infinite merit of Aristotle…that he was the first to undertake this description,” still it was essential “to go further and to ascertain both the systematic connection of these forms and their value.”15 Hence the assumption of truth in logic needed to be replaced by a methodical linkage of its different parts.

Hegel gave his exact reasoning for this later in his work, where he gave a devastating critique of the classic approach to logic. There he argued that in studying the traditional presentations, one is

struck by the inconsequential way in which the species of notions are introduced: there are, in respect of quantity, quality, etc., the following notions. There are, expresses no other justification than that we find such species already to hand and they present themselves empirically. In this way, we obtain an empirical logic — an odd science this, an irrational cognition of the rational. In proceeding thus, logic sets a very bad example of obedience to its own precepts; it permits itself for its own purpose to do the opposite of what it prescribes as a rule, namely that notions should be deduced, and scientific propositions … should be proved.16

If logic is to be true to itself, that is, be true, then it must criticise itself and so prove itself. This could only be done by a chain of reasoning, and so it would be the “systematic connection” of all of its forms, its categories and laws. Dialectical logic, then, is the science of proof. Yet, as regards itself, its self-proving can only occur as self-criticism and so the system of logic, for Hegel, was exactly its self-development.

In eschewing an empirical, external approach, dialectical logic rightly focuses on the immanent logic of what it has under view. In this case, Hegel was setting forth the logic of logic. As he wrote, “the method which I follow in this system of logic — or rather which this system in its own self follows … is the only true method.”17 He argued that this was the correct method because it was “self-evident simply from the fact that it is not something distinct from its object and content; for it is the inwardness of the content, the dialectic which it possesses within itself, which is the mainspring of its advance.”18 Hence, the internal logic of an object is its dialectic and this is precisely the method.

Following from the very logic of logic, Hegel further argued that it was “clear that no expositions can be accepted as scientifically valid which do not pursue the course of this method and do not conform to its simple rhythm, for this is the course of the subject matter itself.”19 In other words, the goal of dialectical logic was to grasp and accurately portray the objective, immanent necessity of a thing’s development and so not introduce any external, haphazard, and subjective considerations.

Dialectic method: Form and content

In discussing Hegel’s dialectical method a distinction must be made between its form and content. The latter refers to the unity of positing and negating, or, more generally, the unity of opposites. According to Hegel, the “one thing needed to achieve scientific progress … is the recognition of the logical principle that negation is equally positive, or that what is self-contradictory does not resolve itself into a nullity … but essentially only into the negation of its particular content.”20

For example, the syllogism is an organic whole. Each succeeding proposition supersedes the previous one and all culminate in the conclusion. The final result is, of course, the negation of the beginning, but it is not nothing; that is, “such a negation is not just negation, but is the negation of the determined fact which is resolved, and is therefore determinate negation; that in the result there is therefore contained in essence that from which the result derives.”21 Since “the result, the negation, is a determinate negation, it has a content. It is a new concept but one higher and richer than the preceding — richer because it negates or opposes the preceding and therefore contains it, and it contains even more than that, for it is the unity of itself and its opposite.”22 To understand a syllogism exactly means to grasp the premises in the conclusion and vice versa.

That is why Hegel pointed out that to “hold fast to the positive in its negative, to the content of the presupposition in the result, this is the most important factor in rational cognition,” and, moreover, “it takes only the simplest of reflections to be convinced of the absolute truth and necessity of this requirement, and as for examples of proofs that testify to this, the whole Logic consists of such proofs.”23 The positive development of the system of logic is simply a series of definite negations, or refutations, of each succeeding form and so, again, dialectical logic proves itself by criticising itself.24

On the other hand, the form of Hegel’s dialectical method refers to what he termed triplicity. In his reformation of formal logic, the height of Hegel’s endeavour was the syllogism. Indeed, properly (that is, dialectically) understood, his system of logic is a giant syllogism made up of subsidiary syllogisms. As he explicitly wrote: “Everything is a syllogism, a universal that through particularity is united with individuality.”25

The final chapter of his Science of Logic, “The Absolute Idea,” provides the most developed presentation of the dialectical method. The reason why this could not have been done at the start was, of course, because it would have then been a presupposition, a bare assertion. It therefore took the whole of logic for the method to prove itself.

In the beginning “a universal first, considered in and for itself, shows itself to be the other of itself.”26 That is, in the course of investigating the nature of a concept, it will inevitably show itself to be more than what initially appeared. For Hegel, this “first immediate now appears as mediated, related to an other, or that the universal appears as a particular. Hence the second term that has thereby come into being is the negative of the first.”27 Here, then, we have the first as positive and immediate, and the second as negative and mediated. As the second arose from the first, this is the unity of opposites.

Yet, recalling that the syllogism is the unity of universal, particular, and individual, only the first two steps have been completed. To continue on, the “second determination, the negative or mediated, is … in its truth … a relation or relationship; for it is the negative, but the negative of the positive, and includes the positive within itself.”28 As the “the first or the immediate is … implicitly the negative,” therefore, “the dialectical moment with it consists in positing in it the difference that it implicitly contains. The second, on the contrary, is itself the determinate moment, the difference or relationship; therefore with it the dialectical moment consists in positing the unity that is contained in it.”29

This second term, as the definite negative of the first, contains the first, and so, as the other of the first is the other of itself. The negative therefore shows itself as positive and so the negative negates itself. In Hegel’s words, the “second negative, the negative of the negative, at which we have arrived, is this sublating of the contradiction,” viz., the contradiction of the first two terms.30 We thus arrive at the third term, or moment, in the form of the method.

This third moment, the conclusion, is however, simultaneously a return to the beginning; the premises are in the conclusion. More specifically, as “self-sublating contradiction this negativity is the restoration of the first immediacy, of simple universality; for the other of the other, the negative of the negative, is immediately the positive, the identical, the universal.”31 The final term is the unity of the first two, of the universal and particular, and so shows itself to be a syllogism. Yet, as Hegel noted, that “it is this unity, as also that the whole form of the method is a triplicity, is, it is true, merely the superficial external side of the mode of cognition; but to have demonstrated even this … must also be regarded as an infinite merit of the Kantian philosophy.”32

Seeing that Hegel said that it was the “infinite merit” of Kant to have applied the form of triplicity, the only reason that he could also describe the latter as simply “superficial,” is because to focus only or mainly on the form, on the appearance, would be one-sided, viz., undialectical. This can be seen from the fact that, years before, he had written that “triplicity was rediscovered by Kantian thought — rediscovered by instinct,” and “it was then elevated to its absolute significance, the true form was set out in its true content.”33 For Hegel, both the form and the content, the appearance and essence, of the method had to be held together.34 Still, it was the essence of the method that was crucial: “dialectic” is “the grasping of opposites in their unity or of the positive in the negative,” and it “the most important aspect of dialectic.”35

Marx, in his afterword to the 2nd German edition of Capital, referred to Hegel’s dialectic as holding a “rational kernel within the mystical shell.”36 Here, Marx is traditionally taken to mean that the dialectic is the kernel and idealism is the shell. This is true, but it is only one aspect of the truth and to remain there is, therefore, to rest in a one-sided and superficial understanding.

More precisely, Marx was also referring to the form of triplicity, because that is the precise mechanism by which Hegel’s idealist system was formed. In fact, as the Old Hegelian Karl Rosenkranz had already noted back in 1869, the application of the form of triplicity was prone to arbitrary schematism among the Hegelian school, and even with Hegel himself.37 For example, according to Rosenkranz, Hegel in his “Philosophy of Right, under the conception of the state power … has set up royal sovereignty as the first, therefore abstract, moment; while in the second edition of the Encyclopedia it is the final and concrete moment.”38

Seeing as the final moment is a return to the first moment, it is understandable that, despite the desire to objectively portray the inner logic of development, a confusion of the two could occur. Further, error could also happen in the transition between the first and second moments, viz., “in regard to that which is posited as the negative … the transition from the general to the special the distinction necessary in itself could very easily be varied, and the immanent antithesis be falsified.”39 If error was possible in the first shift, then the next one only increased that chance.

While the unity of opposites seems to imply triplicity, the truth is that the latter is a false form of the dialectic. The reason is that it privileges identity and unity over difference and contradiction; but the heart of dialectic is precisely contradiction. As Hegel wrote: “That which enables the Notion to advance itself is the already mentioned negative which it possesses within itself; it is this which constitutes the genuine dialectical element.”40 It was its emphasis on identity and its susceptibility to error that made this form undialectical, unscientific, and enabled Hegel to artificially construct his idealist system. To properly apply the dialectic, triplicity must be let go, and so the form of Hegel’s dialectic was unfit to be applied to political economy.

Aside from the above-mentioned statement by Marx, this can also been seen in one of his earliest mature economic writings, the manuscripts known as the Grundrisse. Marx, in his draft introduction, gave a brief review of the different categories which economists regularly grouped along with production, and concluded that “production, distribution, exchange and consumption form a regular syllogism; production is the generality, distribution and exchange the particularity, and consumption the singularity in which the whole is joined together.”41 Marx identified that the relations between the different categories, or economic spheres, formed a Hegelian syllogism.

However, he then went on to comment that it was “admittedly a coherence, but a shallow one.”42 Marx was certainly not denying the truth of what he wrote; indeed, in later years he noted the existence of such syllogisms in subsequent economic writings.43 Rather, he was merely pointing out that its value was quite limited, viz., that it gave, at best, only a surface understanding. The reason for this was that the “task” was not “the dialectic balancing of concepts,” but rather “the grasping of real relations.”44 To accomplish that, historical empirical research was needed.

Marx then moved on to analysing the specific relations between production and the other categories, starting with the former and consumption. Summarising his analysis he wrote that the “identities between consumption and production thus appear threefold.”45 The first was that of “Immediate identity: Production is consumption, consumption is production. Consumptive production. Productive consumption.”46 Here producing is simultaneously consuming: to produce is to consume energy and materials, and consuming produces energy and waste.

The second identity was “that one appears as a means for the other, is mediated by the other: this is expressed as their mutual dependence; a movement which relates them to one another … but still leaves them external to each other.”47 Where in the first identity they are immediately the same, here they are separate, but become the same via their mutual dependence, their mutual mediation. As an example Marx gave the following: “Production creates the material, as external object, for consumption; consumption creates the need, as internal object, as aim, for production.”48

Finally, the third form of identity is where production and consumption, “each of them, apart from being immediately the other, and apart from mediating the other, in addition to this creates the other in completing itself, and creates itself as the other.”49 Marx gave as an example the fact that consumption “accomplishes the act of production only in completing the product as product by dissolving it, by consuming” it, and “production produces consumption by creating the specific manner of consumption; and, further, by creating the stimulus of consumption, the ability to consume, as a need.”50 Here, with each creating the other as itself and itself as the other, we have a self-mediated identity.

This is, of course, Hegel’s form of triplicity, and some of the different terms used to describe it are: immediate, mediate, self-mediation; in itself, for other, in and for itself; indeterminate, determinate, self-determined, positive, negative, the absolutely positive.51 In light of this, it is easy to see why Marx would write that, therefore, there was “nothing simpler for a Hegelian than to posit production and consumption as identical,” and note that this had also “been done not only by socialist belletrists but by prosaic economists themselves, e.g. Say; in the form that when one looks at an entire people, its production is its consumption. Or, indeed, at humanity in the abstract.”52 Using abstraction in the process of reason is a necessary part in all science. But remaining there would be to simply skate on the surface, to hold a one-sided conception and lack any concretisation. Therefore, while production and conception are clearly identical in some aspects, to assert an absolute identity was clearly abstract and wrong.

Doing so also ignored empirical reality and the fact that production and consumption are not and cannot be fully equal; that is, that one actually predominates over the other. Marx noted that “whether production and consumption are viewed as the activity of one or of many individuals, they appear in any case as moments of one process, in which production is the real point of departure and hence also the predominant moment.”53 The act of production is primary and consumption is secondary, and so the former “is the act through which the whole process again runs its course. The individual produces an object and, by consuming it … returns as a productive and self-reproducing individual.”54

While both spheres can be looked at separately or in connection, a Hegelian approach cannot provide a correct view of the real nature of the relations between the two. As Marx argued, treating “society as one single subject is, in addition, to look at it wrongly; speculatively.”55 He was not approaching political economy with either Hegelian speculative philosophy, nor with his own new philosophy. As I have argued elsewhere, Marx had made a materialist critique of Hegel’s dialectic and thrown philosophy overboard, moving on to critical, empirical social science.56 This was the basis for his dialectical critique of political economy. Hence, as the Grundrisse shows, Marx’s dialectical method did not and could not involve Hegel’s form of triplicity.

The premise of political economy

Although Marx built off the achievements of classical political economy, his own work was neither an extension nor a completion of it. He came not to fulfil it, but to abolish it by means of an imminent critique. Marx was, therefore, not a political economist, nor is there such a thing as Marxist political economy. The premises of his work was therefore the opposite of that of Adam Smith and David Ricardo, the greatest representatives of classical political economy. The more specific reason for this was Marx’s twofold estimation of the latter’s premises.

On the one hand, Smith and Ricardo had a shared premise in their approach to political economy which was ahistorical. This did not mean that either man denied that there were previous forms of economy. Rather their ahistorical view was in treating capitalism as eternal and natural; that is, history stops here. Marx, in 1847 noted that political economists “have a singular method of procedure. There are only two kinds of institutions for them, artificial and natural. The institutions of feudalism are artificial institutions, those of the bourgeoisie are natural institutions.”57

He repeated this in 1863, in the unfinished fourth volume of Capital, writing that “a failure, a deficiency of classical political economy is the fact that it does not conceive the basic form of capital, i.e. production designed to appropriate other people’s labour, as a historical form but as a natural form of social production.”58 The specific problem with the ahistorical premise was that it blocked the way to further comprehension, and so led Smith and Ricardo into contradictions:

The value-form of the product of labour is the most abstract, but also the most universal form of the bourgeois mode of production; by that fact it stamps the bourgeois mode of production as a particular kind of social production of a historical and transitory character. If then we make the mistake of treating it as the eternal natural form of social production, we necessarily overlook the specificity of the value-form, and consequently of the commodity-form together with its further developments, the money form, the capital form, etc.59

Despite the great advances made by classical political economy in elucidating aspects of the capitalist mode of production, the inability of its representatives to see its transient nature prevented them from grasping capitalism as a developing organic whole. This great weakness also, ultimately, did not allow them to be consistently critical. Hence they took its existence as something that was naturally good and beneficial.

On the other hand, the greatest strength of classical political economy was the focus of its research. More precisely, Smith, Ricardo, and others “investigated the real internal framework of bourgeois relations of production.”60 They primarily concentrated on the inner structure of capitalist economy and only secondarily on the connection of its outer forms. As Smith himself wrote in 1776: “The causes of this improvement, in the productive powers of labour, and the order, according to which its produce is naturally distributed among the different ranks and conditions of men in the society, make the subject of the first book of this Inquiry.”61

Ricardo repeated this in 1817 in more detail: “The produce of the earth … is divided among three classes of the community; namely, the proprietor of the land, the owner of the stock or capital necessary for its cultivation, and the labourers by whose industry it is cultivated … To determine the laws which regulate this distribution, is the principal problem in Political Economy.”62 For them and for other classical political economists, the goal was to grasp what the relations were between the major economic classes and how that determined how wealth was distributed among them.63

This was achieved by what Marx termed the analytic method, which he also judged in a twofold way. In this approach, classical political economy sought “to reduce the various fixed and mutually alien forms of wealth to their inner unity by means of analysis and to strip away the form in which they exist independently alongside one another.”64 These included, in Ricardo’s words, “rent, profit, and wages.”65

To understand these different forms under which wealth was apportioned to the different classes, they had to be reduced to some type of common basis. Thus, political economists tried to perceive “the inner connection in contrast to the multiplicity of outward forms,” and so, for example, they reduced “rent to surplus profit, so that it ceases to be a specific, separate form” and divested “interest of its independent form and shows that it is a part of profit … it reduces all types of revenue and all independent forms … under cover of which the non-workers receive a portion of the value of commodities, to the single form of profit.”66

What was accomplished by this, above all, was the greater substantiation and formulation of the law of value. For example “Adam Smith declared that the sole source of material wealth or of use-values is labour in general, that is the entire social aspect of labour as it appears in the division of labour.”67 Later on “David Ricardo, unlike Adam Smith, neatly sets forth the determination of the value of commodities by labour-time, and demonstrates that this law governs even those bourgeois relations of production which apparently contradict it most decisively.”68 Thus the application of the analytic method led to the establishment of what Marx described as “the basic law of modern political economy.”69 This is exactly one of the achievements of classical political economy that Marx critically developed.

However, that same method also led Smith, Ricardo, and others to contradicting themselves in presenting the system of capitalist economy. The reason for this lies in the fact that classical political economy, in trying to carry out the needed reduction, left “out the intermediate links”. This was because it was “not interested in elaborating how the various forms come into being,” because it began “from them as given premises.”70 That is, it took an already-finished capitalism as a given. Yet, as Marx wrote to his friend, Dr. Kugelmann:

Science consists precisely in working out how the law of value asserts itself. So if one wishes to ‘explain’ all the phenomenon which appear to contradict the law from the very start, then one would have to provide the science before the science. This is exactly Ricardo’s mistake, when, in his first chapter on value, he takes for granted all the possible categories which should first be explained, in order to provide evidence of their agreement with the law of value.71

Here, in the case of Ricardo, the key problem was that categories were put forth that had not been systematically elucidated, that is, they had not been explained or proven.72 As a result of these missing connections, these gaps, Marx spoke of Ricardo’s work as suffering from “necessarily faulty architectonics.”73 To Marx, this was “not accidental,” but “the result of Ricardo’s method of investigation itself … It expresses the scientific deficiencies of this method of investigation.”74 This was exactly the analytic method, and it clearly formed a parallel with that of Kant and logic.

Marx’s critique

Yet, despite these deficiencies, the method of classical political economy was historically necessary. Thus Marx wrote that it was the “analytical method, with which criticism and understanding must begin,” and, more exactly, that “analysis is the necessary prerequisite of genetical presentation, and of the understanding of the real, formative process in its different phases.”75 Here, he was pointing out that the research and method of classical political economy were the historical, scientific prerequisites of his own work.76

More importantly, in describing his method as “genetical,” he was making a reference to Hegel. The latter, in dialectically linking and so deducing the entirety of logic, described his system in the following words: “Hence the objective logic, which treats of being and essence, constitutes in truth the genetic exposition of the concept.”77 In this method, “the content and determination of the” concept “can be proven solely on the basis of an immanent deduction which contains its genesis.”78 Hegel systematically deduced, proved, each part of logic according to its own internal logic viz., the dialectic.

This is what Marx sought to accomplish in his critique of political economy, and held to be absolutely essential for properly comprehending the logic of the commodity and the development of the value-form. In fact, in 1858, he explicitly described his work as “a Critique of Economic Categories … a critical exposé of the system of the bourgeois economy. It is at once an exposé and, by the same token, a critique of the system.”79

Where Hegel gave a critical exposition of the system of logic, Marx gave a critical exposition of the system of political economy. To recall, each category is one-sided, deficient, and so shows itself to be other than what it is. Thus it falls into contradiction, or rather contains the latter. The overcoming of the category’s deficiency is the resolution of its contradiction. This, in turn, gives rise to a higher, more concrete category, which again proves to be contradictory, again is resolved, negated, and in this way an organic whole is formed.

However, although there is a real parallel here, a mirroring, there was also a very real, crucial difference between Marx’s project of critique and that of Hegel’s. That is, just as Marx’s premises differed from political economy, his premises also differed from Hegel’s. He once explained this in an 1868 letter: “my method of exposition is not Hegelian, since I am a materialist, and Hegel an idealist. Hegel’s dialectic is the basic form of all dialectic, but only after being stripped of its mystical form, and it is precisely this which distinguishes my method.”80

Marx accepted the content of Hegel’s method of dialectical critique, but not its form, and this revolved around its idealist basis. He later echoed this, famously declaring that his

dialectical method is, in its foundations, not only different from the Hegelian, but exactly opposite to it. For Hegel, the process of thinking … is the creator of the real world, and the real world is only the external appearance of the idea. With me the reverse is true: the ideal is nothing but the material world reflected in the mind of man, and translated into forms of thought.81

For Marx “ideas, categories,” are “the ideal abstract expressions of … social relations.”82 Therefore, “economic categories are but abstract expressions of these actually existing relations and only remain true while these relations continue to exist.”83 That is, Marx did not deduce the categories of capital according to dialectical logic. Rather he deduced them from their empirical relations within the developing organic whole of capitalism. Hence his critique was of the actual, material functioning of the latter and its ideal expression. Ergo, while dialectical logic guided his research, it did not dictate his conclusions. This is why Kozo Uno’s criticism of the derivation of categories in Marx’s critique was incorrect and beside the point.84

The commodity

At this point, it may still not be clear as to why Marx began his critique of political economy with the commodity. He wrote that it was the “first category in which bourgeois wealth presents itself.”85 He also gave this fact another formulation, writing in the first chapter of Capital that the “wealth of societies in which the capitalist mode of production prevails appears as an ‘immense collection of commodities’; the individual commodity appears as its elementary form.”86 It should be noted that he used the words “presents” and “appears.” Marx was implying that he was starting on the surface of capitalist reality, viz., that he was starting with its form, its appearance, and, in the course of his investigation, would move towards its content or essence.

However, there was an even deeper reason for starting with the commodity. This was because it is the historical and logical starting point for the genesis of the capitalist mode of production and all of its contradictions. As Marx observed, the exchange of commodities “begins not between the individuals within a community, but rather at the point where the communities end — at their boundary, at the point of contact between different communities.”87 It is at the exterior “where barter begins and moves thence into the interior of the community, exerting a disintegrating influence upon it.”88

All peoples originally lived communally and it was the development of barter, of simple commodity exchange, which eroded the former by encouraging new tastes, new needs, thus promoting the further development of the division of labour within and between communities. From a secondary, accidental act, it became over time, primary and necessary, hence leading humanity to become dependent on the exchange of commodities. This is why Marx wrote that “for bourgeois society, the commodity-form of the product of labour, or the value-form of the commodity, is the economic cell-form.”89 That is, capitalism organically grew out of the commodity, and so the concrete understanding of its development and functioning, of its internal logic, required exactly this beginning.

The individual commodity shows itself to have “a twofold aspect — use-value and exchange-value.”90 That is, it is a unity of opposites. The first aspect refers to the fact that “a thing … through its qualities satisfies human needs of whatever kind,” and so all useful things “for example, iron, paper, etc., may be looked at from the two points of view of quality and quantity.”91 Thus, in the example, iron and paper differ qualitatively and quantitatively viz., they weigh differently and are produced in different amounts. As use-values, commodities are separate and stand apart. However, as to the second aspect, exchange-value, it “seems at first to be a quantitative relation, the proportion in which use-values are exchanged for one another. In this relation they constitute equal exchangeable magnitudes.”92 As exchange-values, commodities are qualitatively and quantitatively the same and are connected and related via exchange.

The question that arises here is how are things that are different treated as equal? What is the basis of their equality? Marx noted that, in the first place, the act of exchange itself treats dissimilar things as similar; that is by “abstraction from the use-value. As far as the exchange-value is concerned, one commodity is, after all, quite as good as every other, provided it is present in the correct proportion.”93

Yet, the exchange relation itself “changes constantly with time and place. Hence exchange-value appears to be something accidental and purely relative, and consequently an intrinsic value, i.e. an exchange-value that is inseparably connected with the commodity, inherent in it, seems a contradiction in terms.”94 But if one commodity can be exchanged for any other commodity, then there must be a common basis outside exchange. The latter only seemed, appeared, to be the basis of their equality. There is, in truth, a deeper reason.

Marx wrote, “Commodities as objects of use or goods are corporeally different things. Their reality as values forms … their unity.”95 That is, when we abstract from use-value, we are left with exchange-value. If we then abstract from the latter — that is, the exchange relation — we are left with value.

Further, an object can be a use-value without being a commodity; for example, if I grow vegetables and eat them myself. However, to be a commodity an object must be made for exchange, must be exchangeable, it must have value; exchangeability is their common aspect. Yet, exchange is a social act. Thus, as Marx noted, this “unity does not arise out of nature but out of society. The common social substance which merely manifests itself differently in different use-values, is — labour.”96 Of course, before objects can be exchanged they have to actually be produced. Thus the real basis for the unity of all commodities is that they are products of labour.

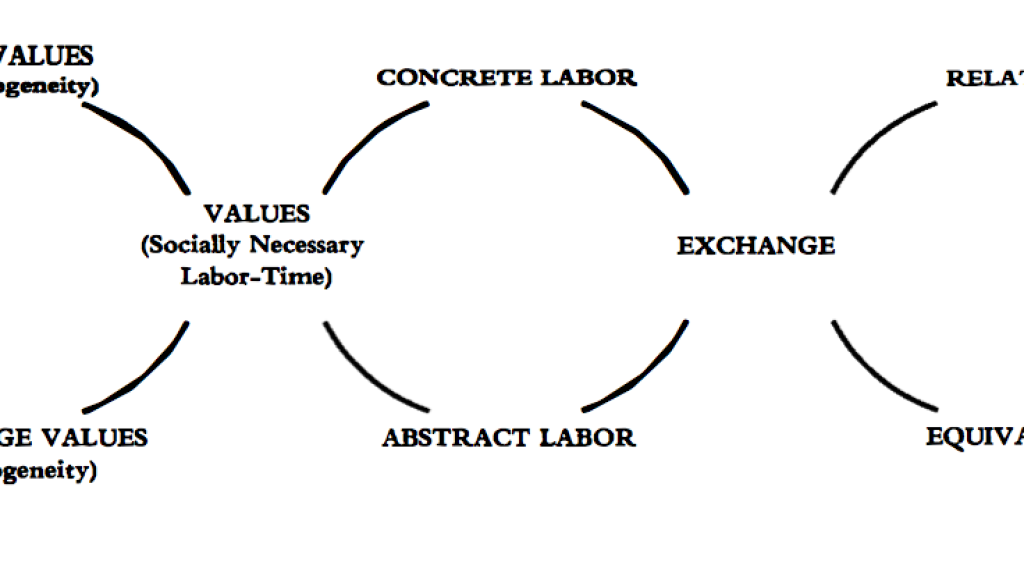

Starting with the category of the individual commodity, Marx showed the contradictory aspects contained therein. Analysing these two categories (use-value and exchange-value), separately and together, resulted in arriving at the next category viz., labour. In analysing the latter, we will see, yet again, a unity of opposites.

Marx, referring to, for example, a coat and linen explained that as they “are qualitatively different use-values, so also are the forms of labour through which their existence is mediated — tailoring and weaving.”97 As there are different types of use-values, so are there different types of useful, concrete labour that produced them. Yet, as an abstraction from use-value is made in exchange, so also is an abstraction made

from the material constituents and forms which make it a use-value. It is no longer a table, a house, a piece of yarn or any other useful thing … Nor is it any longer the product of the labour of the joiner, the mason or the spinner, or of any other particular kind of productive labour. With the disappearance of the useful character of the products of labour, the useful character of the kinds of labour embodied in them also disappears … They can no longer be distinguished, but are all together reduced to the same kind of labour, human labour in the abstract.98

Abstract labour is “human labour pure and simple, the expenditure of human labour in general … the expenditure of simple labour-power, i.e. of the labour-power possessed in his bodily organism by every” human “on the average, without being developed in any special way.”99 Thus, as the commodity has a twofold character, so does the labour which produces it. Marx was the first to prove this and argued that it was “crucial to an understanding of political economy.”100 The reason for this will be seen below.

It is important to emphasise that it was not only Marx forming the above abstractions. It happens every time commodities are exchanged. For example, in exchanging a coat for linen, and vice versa, the owners of those objects are equating “the coat as a thing of value to the linen,” and so equating “the labour embedded in the coat with the labour embedded in the linen.”101 Although it is “the tailoring which makes the coat,” which “is concrete labour of a different sort from the weaving which makes the linen,” the very “act of equating tailoring with weaving reduces the former in fact to what is really equal in the two kinds of labour, to the characteristic they have in common of being human labour.”102

So, while labour in its concrete form gives a commodity its use-value, labour in its abstract form gives it value. In fact, it “is only the expression of equivalence between different sorts of commodities which brings to view the specific character of value-creating labour, by actually reducing the different kinds of labour embedded in the different kinds of commodity to their common quality of being human labour in general.”103 Labour, therefore, is a contradiction, a relation within itself.

It will be recalled that, as a use-value, a commodity differs mainly qualitatively, and, as exchange-value, primarily quantitatively. But, if labour is the basis of value, then how is value to be determined? Marx answered that it was by “the quantum of the ‘value-forming substance’ (i.e. labour) which is contained in it. The quantity of labour itself is measured by its temporal duration and the labour-time in turn possesses a measuring rod for particular segments of time, like hour, day, etc.”104 It being the average human labour which forms value, therefore it is the amount of socially-necessary labour time for the production of a commodity which determines the quantity of the latter’s value.105

This is important because, again, as the contradiction within labour is expressed in the contradictory nature of the commodity, so developments in the former affect the latter. One expression of this was described by Marx as follows: “an increase in the quantity of use-values constitutes an increase in material wealth … Nevertheless, an increase in the amount of material wealth may correspond to a simultaneous fall in the magnitude of its value. This contradictory movement arises out of the twofold character of labour.”106 That is, an increase in the productive power of labour is manifested in the contradiction of a simultaneous growth of use-values (material wealth) and decrease of value (social wealth).

This state of affairs is rooted in the relations of production. That is, the things that humans make can only become commodities when they are “the products of mutually independent acts of labour, performed in isolation,” that is performed by private individuals, or groups thereof.107 Commodities are the result of private labour, and so the products of labour “only appear as commodities, or have the form of commodities, in so far as they possess a double form, i.e. natural form and value form.”108

The value form is precisely its social form. What this means is that the labour which produces commodities is private and not immediately social. It can only prove itself as such, only become so, by its products being exchanged. Therefore, “the exchange-value of commodities is … a mutual relation between various kinds of labour of individuals regarded as equal and universal labour, i.e., nothing but a material expression of a specific social form of labour.”109 Private producers, then, relate their different labours via the social act of exchanging material objects; hence, the material relations between commodities are the form, the appearance of the social relations between producers.

This is clear when considering the opposite situation. In the case of a “communal system,” this “mode of production … prevents the labour of an individual from becoming private labour and his product the private product of a separate individual; it causes individual labour to appear rather as the direct function of a member of the social organisation.”110 The labour of a member is immediately individual and social, and hence no commodities are produced, nor exchanged. On the other hand, that labour “which manifests itself in exchange-value appears to be the labour of an isolated individual,” and it only “becomes social labour by assuming the form of its direct opposite, of abstract universal labour,” i.e. that labour which produces value.111

As a result, where commodity production occurs, “it is a characteristic feature of labour which posits exchange-value that it causes the social relations of individuals to appear in the perverted form of a social relation between things.”112 Although existing in society, since production is carried on privately, we have the contradiction that social labour is not social and can only become so via the medium of exchanging objects, viz., by treating relations between people as actually relations among objects. It is precisely the logic of this process that leads to producers becoming dependent upon and ultimately dominated by their own products. This is why grasping the twofold nature of labour is necessary for critically understanding bourgeois political economy.

The value-form of the commodity

Marx’s analysis of labour and the contradiction contained therein returns us to exchange as the expression of the social nature of value. Now arises the next category, the value-form, which, like previous categories, will show itself to be a contradiction. Since commodities have a socially “objective character as values only in so far as they are all expressions of an identical social substance, human labour,” then “their objective character as values is … purely social,” and “can only appear in the social relation between commodity and commodity.”113

Presently, under capitalism, “commodities have a common value-form,” which is “the money-form.”114 Therefore, at this stage of the analysis, Marx had “to perform a task never even attempted by bourgeois economics,” which was to “show the origin of this money-form,” by tracing “the development of the expression of value contained in the value-relation of commodities from its simplest, almost imperceptible outline to the, dazzling money-form.”115 Since the genesis of capitalism develops from its simplest form, its economic cell-form, the further course moves from the simple to the complex, from the abstract to the concrete. As the “simplest value-relation is … one commodity to another commodity of a different kind,” so, “the relation between the values of two commodities supplies us with the simplest expression of the value of a single commodity.”116

Marx began with what he termed the “simple value-form.” He expressed it with the example of “20 yards of linen = 1 coat or 20 yards of linen are worth 1 coat.”117 As can be clearly seen from the latter, the form of value has a twofold, contradictory nature. It being a relation, it is structured by two poles that Marx termed “relative value-form and equivalent form.”118 The two commodities function differently depending on which pole they stand at. In this case, the

linen is the commodity which expresses its value in the body of a commodity different from it, the coat. On the other hand, the commodity-type coat serves as the material in which value is expressed. The one commodity plays an active, the other a passive role. Now we say of the commodity which expresses its value in another commodity: its value is represented as relative value, or is in the relative value-form. As opposed to this, we say of the other commodity, here the coat, which serves as the material of the expression of value: it functions as equivalent to the first commodity or is in the equivalent form.119

This is a true unity of opposites because the poles of this relation are at once “reciprocally conditioning and inseparable,” and “mutually excluding or opposed extremes.”120 Marx also noted, the same commodity cannot stand at both poles, i.e. two different commodities are needed. And, while the equation “20 yards of linen = 1 coat” implies its opposite, that is only for the owner of the other commodity, the coat. That is, the equation is reversed from their perspective.121 Two different commodities are equated, and the two poles form one relation.

Again, both objects in the value-form are equated qualitatively and quantitatively, viz., as both being values of the same amount. Yet for this to occur, both commodities have to be products of different labour, have to be different use-values, and so have different physical existences. In Marx’s words: “by means of the value-relation the value of the commodity is expressed in the use-value of another commodity, i.e. in the body of another commodity different from itself.”122

The significance of this is that although a commodity is a unity of use-value and exchange-value, the latter can only be seen in exchange, it can only take shape within the value-form. Here, the linen “possesses its value-form in its relation of equality with the coat. Through this relation of equality the body of another commodity, sensibly different from it, becomes the mirror of its own existence as value … of its own character as value.”123 In other words, the unity of the two aspects of the commodity only comes to be by division, by falling asunder in the exchange process.

Marx pointed out that, in this division, the equivalent form was the site of a number of dialectical transitions. First, as already discussed above, “use-value becomes the form of appearance of its opposite, of value.”124 Secondly, “concrete labour becomes the form of appearance of its opposite, abstract human labour.”125 Thirdly, “private labour becomes the form of its opposite, labour in immediately social form.”126 All of these shifts occur because of the basic contradiction of a society of separate producers, whose collectivity is only produced and mediated via exchange.

It is because of these contradictions that there exists what Marx called the “fetishism” of commodities, and which “emerges more strikingly in the equivalent-form than in the relative value-form.”127 With the former, it “consists precisely in the fact that the bodily or natural form of a commodity counts immediately as the social form, as the value-form for another commodity,” and, as a result, “to possess the equivalent-form appears as the social natural property … pertaining to it by nature, so that hence it appears to be immediately exchangeable with other things just as it exists for the senses.”128 That is, commodities only exist because humans carry on separate, private labour and exchange their products; that is, only because of social acts, since, in the equivalent form, the physical body of the commodity counts as value, thereby what is social becomes natural. Value is thus not seen as an expression of human activity, but as something inherent in the objects.

A use-value needs “the value-form in order for it to possess the commodity-form, i.e. for it to appear as a unity of the opposites use-value and exchange-value. The development of the value-form is hence identical with the development of the commodity-form.”129 As Marx wrote, “If we replace: 20 yards of linen = 1 coat … by the form: 20 yards of linen = 2 Pounds Sterling … then it becomes obvious at first glance that the money-form in nothing but the further development of the simple value-form of the commodity.” So, in order to grasp this higher form in its full truth, i.e. in its whole development, it is necessary “to consider the series of metamorphoses through which the simple commodity form … must run in order to take on the shape … ‘20 yards of linen = 2 Pounds Sterling’.”130 Money cannot be understood outside of this organic genesis.

With the development of commodity production there arises the possibility that, for example, linen has “just as many different simple expressions of value as there are different sorts of commodities … therefore, its complete relative expression of value consists not in an isolated simple relative expression of value but in the sum of its simple relative expressions of value.”131 With this we get the second form of value, what Marx termed the “Total or Expanded Value-form,” which is expressed as “20 yards of linen = 1 coat or = 10 pounds of tea or = 40 pounds of coffee or = 1 quarter of wheat or = 2 ounces of gold or = ½ ton of iron or = etc.”132

With this new form, the poles of the equation therefore also change. We have the “expanded relative value-form” and the “particular equivalent-form.”133 This series is inherently unlimited as new commodities are brought into exchange, and so the relative pole is expressed in so many separate particular equivalents. Yet Marx noted that this newest category suffered from a number of “deficiencies,” which affected both poles viz. “the relative expression of value of linen is incomplete … because the series which represents it never concludes.” So, “it consists of a motley mosaic of different … expressions of value,” and further, the “deficiencies of the expanded relative value-form are reflected in the equivalent-form … Since the natural form of each single type of commodity is here a particular equivalent-form beside innumerable other particular equivalent-forms there exist only limited equivalent-forms,” which exclude each other.134

However, as the owner of the linen exchanges it “with many other commodities and hence expresses the value of his commodity in a series … then necessarily the many other possessors of commodities must also exchange their commodities with linen and hence express the values of their different commodities in the same third commodity, the linen.”135 The above series or form of value therefore implies its own converse.

This gives rise to the third form, the “General Value-form,” where now all commodities stand in the relative value-form, except the linen stands alone in the equivalent form.136 Here each particular commodity in the series expresses its value in the body of a single commodity. So, the expression of a commodity’s value “in linen, now distinguishes the commodity not only as value from its own existence … as a useful object, i.e. from its own natural form, but at the same time relates it as value to all other commodities, to all commodities as equal to it … it possesses general social form.”137 By all commodities treating a single other commodity as equivalent, they now truly exist for each other as values, as being actually qualitatively equal. As the relative value-form is general, so now is the equivalent form general.

The development of the value-form took place via the contradiction of its two aspects and vice versa, hence the “polar opposition … of relative value-form and equivalent-form … develops and hardens … in the same measure as the value-form as such is developed.”138 That is, in the first form any commodity can stand at either pole as long as any other different commodity is related to it. However, by the third form, only one commodity can stand on one side, all the others standing in opposition. Thus we have moved from the relation of one to one, one to many, and finally many to one.

This takes us to the fourth and final form, viz., the money-form. This is a historical process and over time “the general equivalent-form may pertain now to this now to that commodity in turn.”139 Once a single commodity is finally excluded and treated as the general equivalent, at that point “the unified relative value-form has won objective stability and general social validity,” and so, now, “the specific type of commodity with whose natural form the equivalent form coalesces … socially becomes the money-commodity or functions as money … A definite commodity, gold, has historically conquered this privileged place amongst the commodities.”140 That is, all commodities now express their value in a certain amount of gold, and hence the “simple relative expression of value of a commodity, e.g. linen, in the commodity which is already functioning as the money-commodity, for example gold, is the price-form.”141

Conclusion

Marx’s dialectical critique began with the commodity and revealed two aspects: use- and exchange-value. The course of analysis then led to a new category, labour, which itself also had two aspects. The analysis of these, in turn, led to the form of exchange-value viz. the value-form and its two aspects, relative and equivalent form, and then passed through the simple form, the expanded form, the general form, and finally, the money form of value.

Marx’s analysis of the commodity was, therefore, the positing, development, and negation, of the unity of opposites contained in each successive category. These contradictions reflected deeper ones in the relations of production and eventually gave rise to money. The stages of the form of value were therefore the development and resolution-negation of the contradiction between use-value and exchange-value, between concrete and abstract labour, between private and social labour. Marx’s method proved that the logic of materialism is not merely the only true logic, but is the logical result of the dialectic of the material.

Finally, it will be recalled that the commodity is the economic cell-form and that its contradictions are the basis of all other contradictions in capitalism. For example, as the contradictions with simple exchange or barter develop into the contradiction between commodity and money, so exchange becomes divided between “purchase and sale” and this “contains the general possibility of commercial crises, essentially because the contradiction of commodity and money is the abstract and general form of all contradictions inherent in the bourgeois mode of labour.”142

Since crises are inherent in capitalism, the only ultimate solution, and hence resolution, of its contradictions, is to do away with commodity production, and thus of money, capital, and wage labour, and to institute “a society composed of associations of free and equal producers, carrying on the social business on a common and rational plan.”143 Anything less than that is simply the reforming and recuperating of capitalist relations of production.

- 1

Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume One, tran. Ben Fowkes (New York: Vintage Books, 1977), 89.

- 2

A final, added difficulty is that the first three chapters of Capital are a summary of Marx’s earlier book, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, where many aspects were dealt with more in-depth. There are real benefits to studying Marx’s critique in both presentations, along with the appendix to the first edition of Capital.

- 3

Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, tran. J.M.D. Meiklejohn and ed. Vasilis Politis (London: J.M. Dent, 2002), 4-5.

- 4

Ibid., 5.

- 5

Ibid., 5.

- 6

Ibid., 5.

- 7

Immanuel Kant, Lectures on Logic, tran. and ed. J. Michael Young (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 438.

- 8

“That from the earliest times logic has traveled this secure course can be seen from the fact that since the time of Aristotle it has not had to go a single step backwards, unless we count the abolition of a few dispensable subtleties or the more distinct determination of its presentation, which improvements belong more to the elegance than to the security of that science. What is further remarkable about logic is that until now it has also been unable to take a single step forward, and therefore seems to all appearance to be finished and complete.” Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, tran. and ed. Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 106.

- 9

“By an architectonic I understand the art of systems. Since systematic unity is that which first makes ordinary cognition into science, i.e. makes a system out of a mere aggregate of it, architectonic is the doctrine of that which is scientific in our cognition in general, and therefore necessarily belongs to the doctrine of method.” Ibid., 691.

- 10

G.W. F. Hegel, Hegel’s Science of Logic, tran. A.V. Miller (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1969), 25.

- 11

Ibid., 27.

- 12

Ibid., 594.

- 13

Ibid., 595.

- 14

Ibid., 595.

- 15

Ibid., 595.

- 16

Ibid., 613.

- 17

Ibid., 54.

- 18

Ibid., 54.

- 19

Ibid., 54.

- 20

G. W. F. Hegel, The Science of Logic, tran. and ed. George Di Giovanni (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 33.

- 21

Ibid., 33.

- 22

Ibid., 33.

- 23

Ibid., 744.

- 24

Each category, judgement, and syllogism, being only one aspect, is therefore one-sided, deficient, and the progress of the system consists in showing this and remedying it by developing and resolving its series of contradictions. As Hegel wrote in the Phenomenology, “a so-called basic proposition or principle of philosophy, if true, is also false, just because it is only a principle. It is, therefore, easy to refute it. The refutation consists in pointing out its defect; and it is defective because it is only the universal or principle, is only the beginning. If the refutation is thorough, it is derived and developed from the principle itself, not accomplished by counter-assertions and random thoughts from outside. The refutation would, therefore, properly consist in the further development of the principle, and in thus remedying the defectiveness, if it did not mistakenly pay attention solely to its negative action, without awareness of its progress and result on their positive side too – The genuinely positive exposition of the beginning is thus also, conversely, just as much a negative attitude towards it, viz., towards its initially one-sided form of being immediate or purpose.” See, G.W.F. Hegel, Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, tran. A.V. Miller (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 13.

- 25

Hegel, Hegel’s Science of Logic, 669.

- 26

Ibid., 833-834.

- 27

Ibid., 834.

- 28

Ibid., 834-835.

- 29

Ibid., 835.

- 30

Ibid., 835.

- 31

Ibid., 836.

- 32

Ibid., 836-837.

- 33

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, The Phenomenology of Spirit, tran. and ed. by Terry Pinkard (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 30.

- 34

For a more detailed and extensive treatment of the relation between the form and content of Hegel’s dialectical method see, Jason Devine, “From Kautsky and the Bolsheviks, to Hegel and Marx: Dialectics, the triad and triplicity,” accessed 13 July 2025, https://links.org.au/kautsky-and-bolsheviks-hegel-and-marx-dialectics-triad-and-triplicity

- 35

Hegel, Hegel’s Science of Logic, 56.

- 36

Marx, Capital, 103.

- 37

Karl Rosenkranz, Hegel as the National Philosopher of Germany, tran. Geo. S. Hall (St. Louis: Gray, Baker & Co., 1874), 34-35.

- 38

Ibid., 34.

- 39

Ibid., 34.

- 40

Hegel, Hegel’s Science of Logic, 55.

- 41

Karl Marx, Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy, tran. Martin Nicolaus (New York: Vintage Books, 1973), 89.

- 42

Ibid., 89.

- 43

Jason Devine, “Dialectical logic in Plato’s ‘Parmenides’, Hegel’s ‘Logic’ and Marx’s ‘Critique of Political Economy’,” accessed 13 July 2025, http://links.org.au/dialectical-logic-plato-parmenides-hegel-marx-critique-political-economy

- 44

Ibid., 90.

- 45

Ibid., 92.

- 46

Ibid., 93.

- 47

Ibid., 93.

- 48

Ibid., 93.

- 49

Ibid., 93.

- 50

Ibid., 93.

- 51

In Hegel’s terminology, self is synonymous with absolute, infinite, and freedom. Thus self-mediation can also be written as absolute mediation, or infinite mediation, etc.

- 52

Marx, Grundrisse, 93-94.

- 53

Ibid., 94.

- 54

Ibid., 94.

- 55

Ibid., 94.

- 56

Jason Devine, “1843-1844: Marx’s Feuerbachian Phase,” accessed 13 July 2025, https://links.org.au/1843-1844-marxs-feuerbachian-phase

- 57

Karl Marx, The Poverty of Philosophy: Answer to the “Philosophy of Poverty” by M. Proudhon (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1978), 112.

- 58

Karl Marx, Theories of Surplus Value: Volume IV of Capital, Part III (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1975), 500-501.

- 59

Marx, Capital, 174.

- 60

Ibid., 174-175.

- 61

Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, Books I-III, ed. by Andrew Skinner (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1979), 105.

- 62

David Ricardo, On The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (London: Dent, 1978), 3.

- 63

“Economists like Adam Smith and Ricardo, who are the historians of this epoch, have no other mission than that of showing how wealth is acquired in bourgeois production relations, of formulating these relations into categories, into laws, and of showing how superior these laws, these categories, are for the production of wealth to the laws and categories of feudal society.” Marx, The Poverty of Philosophy, 115.

- 64

Marx, Theories of Surplus Value, Part III, 500.

- 65

Ricardo, On The Principles, 3.

- 66

Marx, Theories of Surplus Value, Part III, 500.

- 67

Karl Marx, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (New York: International Publishers, 1989), 59.

- 68

Ibid., 60.

- 69

Ibid., 55.

- 70

Marx, Theories of Surplus Value, 500.

- 71

Karl Marx, “Marx to Kugelmann, July 11, 1868,” in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Letters on ‘Capital’, tran. Andrew Drummond (London: New Park Publications, 1983), 148.

- 72

“Thus one can see that in this first chapter not only are commodities assumed to exist—and when considering value as such, nothing further is required—but also wages, capital, profit, the general rate of profit and even, as we shall see, the various forms of capital as they arise from the process of circulation.” Karl Marx, Theories of Surplus Value: Volume IV of Capital, Part II (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1975), 168.

- 73

Ibid., 166.

- 74

Ibid., 167.

- 75

Marx, Theories of Surplus Value, Part III, 500.

- 76

“Of course the method of presentation must differ in form from that of inquiry. The latter has to appropriate the material in detail, to analyse its different forms of development and to track down their inner connection. Only after this work has been done can the real movement be appropriately presented.” Marx, Capital, 102.

- 77

Hegel, Science of Logic, 509.

- 78

Ibid., 514.

- 79

Karl Marx, “Marx to Ferdinand Lassalle, 22 February 1858,” in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works Volume 40: 1856-59 (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1983), 270.

- 80

Karl Marx, “Marx to Ludwig Kugelmann, 6 March 1868,” in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works Volume 42: 1864-68 (New York: International Publishers, 1987), 544.

- 81

Marx, Capital, 102.

- 82

Karl Marx, “Marx to P.V. Annenkov in Paris,” in Karl Marx, The Poverty of Philosophy: Answer to the “Philosophy of Poverty” by M. Proudhon (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1978), 174.

- 83

Ibid., 172; “The categories of bourgeois economics…are forms of thought which are socially valid, and therefore objective, for the relations of production belonging to this historically determined mode of social production, i.e. commodity production.” Marx, Capital, 169.

- 84

“It cannot be doubted that Marx had an accurate grasp of the true nature of the commodity-economy, although there remain some methodological ambiguities…[for instance; the misleading title of the first volume de-emphasises the primacy of the circulation-forms; the premature and unnecessary reference to the labour theory of value in the early part of Capital frequently beclouds the discussion of commodity circulation, etc.].” Kozo Uno, Principles of Political Economy: Theory of a Purely Capitalist Society, tran. T. Sekine (Sussex: Harvester Press, 1980), xxiv.

- 85

Marx, Grundrisse, 881.

- 86

Marx, Capital, 125.

- 87

Marx, Grundrisse, 882.

- 88

Marx, A Contribution, 50.

- 89

Marx, Capital, 90.

- 90

Marx, A Contribution, 27.

- 91

Marx, Capital, 125.

- 92

Marx, A Contribution, 28.

- 93

Karl Marx, “The Commodity,” in Karl Marx, Value: Studies by Marx, tran. Albert Dragstedt (London: New Park Publications, 1976), 8-9.

- 94

Marx, Capital, 126.

- 95

Marx, “The Commodity,” 9.

- 96

Ibid., 9.

- 97

Marx, Capital, 132.

- 98

Ibid., 128.

- 99

Ibid., 135.

- 100

Ibid., 132.

- 101

Ibid., 142.

- 102

Ibid., 142.

- 103

Ibid., 142.

- 104

Marx, “The Commodity,” 9.

- 105

Marx, in his discussion of how labour is the substance of value, noted that he was “not speaking here of the wages or value the worker receives for (e.g.) a day’s labour, but of the value of the commodity in which his day of labour is objectified. At this stage of our presentation, the category of wages does not exist at all.” See, Marx, Capital, 135. This is because Marx was not yet discussing capital and hence wage labour, and, moreover, he had not yet even discussed the category of money. Thus, he was clearly referring to a pre-capitalist relation. Indeed, as Marx noted “Aristotle’s conception of money was considerably more complex and profound than that of Plato…he describes very well how as a result of barter between different communities the necessity arises of turning a specific commodity, that is a substance which has itself value, into money.” See Marx, A Contribution, 117. As commodity production and exchange precede money, therefore they also precede capital, both logically and historically. Therefore, when Uno wrote that “Commodity production must assume the form of capital rather than of commodity. This means that commodity production or the production process of capital can be introduced only after the conceptual development of the form of commodity into that of capital,” he shows that he missed the fact that commodity production took place before the capitalist mode of production, that the latter grew out of the former. See, Uno, Principles of Political Economy, xxviii.

- 106

Marx, Capital, 136-137.

- 107

Ibid., 132.

- 108

Ibid., 138.

- 109

Marx, A Contribution, 35.

- 110

Ibid., 34.

- 111

Ibid., 34.

- 112

Ibid., 34.

- 113

Marx, Capital, 138-139.

- 114

Ibid., 139.

- 115

Ibid., 139.

- 116

Ibid., 139.

- 117

Karl Marx, “The Value-Form,” Capital and Class 4 (Spring, 1978): 134.

- 118

Ibid., 134.

- 119

Ibid., 134-135.

- 120

Ibid., 135.

- 121

Ibid., 135.

- 122

Ibid., 137.

- 123

Ibid., 137.

- 124

Ibid., 138.

- 125

Ibid., 139.

- 126

Ibid., 140.

- 127

Ibid., 143.

- 128

Ibid., 143.

- 129

Ibid., 144.

- 130

Ibid., 144.

- 131

Ibid., 144-145.

- 132

Ibid., 145.

- 133

Ibid., 145.

- 134

Ibid., 145-146.

- 135

Ibid., 146.

- 136

Ibid., 146.

- 137

Ibid., 146.

- 138

Ibid., 148.

- 139

Ibid., 149.

- 140

Ibid., 149.

- 141

Ibid., 150.

- 142

Marx, A Contribution, 96.

- 143

Karl Marx, “The Nationalisation of the Land,” in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works Volume 23: 1871-74 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1988), 136.