Anti-imperialism and Maduro’s Venezuela: Myths and facts

An important debate is occurring on LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal regarding the nature of the Nicolás Maduro regime in Venezuela. So far, there have been contributions by Gabriel Hetland, Steve Ellner, Emiliano Terán Mantovani and Pedro Eusse.

We can divide these contributions in two: those who consider that Venezuela’s current institutional, political and economic shift has been largely caused by imperialism (Ellner); and those who, while not denying the subsequent role of sanctions, view Maduro’s negligence and ideological deviation as the fundamental cause for the current situation (Hetland, Terán and Eusse).

The intention of my contribution has two aims: first, to put forward some quantitative data (which Ellner rightly points out is needed) to better understand the context and situation; and second, to develop several qualitative assessments that can provide us with a better overall analytical framework.

Venezuela and imperialism

Ellner correctly notes in his July 23 contribution that debates on the conduct of socialist governments under attack from imperialism have been a constant feature of polemics among different left currents.

In the debate on Venezuela, I am reminded of French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre’s reflections on the Soviet Union’s occupation of Hungary after the 1956 popular revolt, aptly titled, The Ghost of Stalin.

Paraphrasing Sartre, in this discussion we have been asked to believe that we must — based on universal reasons, and therefore ones acceptable to the left — deny any possibility of new internal political forces emerging in Venezuela.

Rather, our only option is to accept the chaos and tyranny that reigns in Venezuela. The reason given is that events in Venezuela cannot be judged on their own merits: they can only be considered in relation to the impacts they might have on imperialism’s offensive or the emergence of a very hypothetical “multipolar” world.

We are, of course, aware of imperialism’s offensive and its multiple attacks on the country. But we need a clear understanding of the concept of imperialism, if we are to avoid it being used as a marketing tool by activists in the Global North, similar to terms such as ecologism or mindfulness.

Ellner would know, given his Marxist background, that economic categories express historically determined social relations, both nationally and globally. Not taking this into account when considering imperialism, for example, can lead to it being simplistically understood as a relationship between an oppressed nation and an oppressor power.

In Venezuela’s case, we can refute such a simplistic view by recalling — even though many try hard to forget — that prior to the blockade of our oil industry, there existed open collaboration between the country’s national capitalists and the destabilising interests of the Global North. Those capitalists, which sought to starve us to death between 2016-19, were and still are part of imperialism’s internal tentacles.

Imperialism, much like productive forces and the market, is not an abstract category. It is the logic of finance capitalism, with historically constituted relations, involving importing companies, distributors, patents, investment funds, mechanisms of pressure, etc.

Imperialism may be very visible when it takes the form of sanctions, but it also exists in the form of national capitalists who exploit workers while promoting monopolies and capital flight.

In Venezuela, as Domingo Alberto Rangel would say, we have a capitalism that was born old and with the direct help of imperial capital. That means its interests are one and the same.

One only has to look at where the country’s big financial groups hoard their resources. Does Ellner know, for example, where our new capitalist friend, the Grupo Mistral, keeps its profits? It should come as no surprise that they are certainly not patriotic enough to keep them in Venezuela.

In that sense, workers struggling against unjustified dismissals by a transnational, environmentalists in the Mesa de Guanipa in Anzoátegui state struggling against the overexploitation of aquifers by the transnational Ouro Branco, those demanding transparency over oil contracts signed with Chevron, and those opposing the handing over of more than 600 state enterprises under very irregular conditions, are all part of the anti-imperialist struggle.

What is not part of the anti-imperialist struggle, however, is respecting the assets and debts of more than 15 US and European oil transnationals operating in Venezuela, while the home countries of these companies freeze and seize our assets.

The same is true of paying more than US$71 billion to international financial creditors between 2013-18 , despite knowing that they could block Venezuela from accessing international loans and the SWIFT payment system at any time.

It is all well and good to rhetorically denounce imperialism; as spectators watching on from other latitudes, it can make us feel better and more enthusiastic. But for those of us caught up in the middle of the war, this is purely anecdotal.

This nuance and context is also needed when characterising the current government.

Some quantitative data: the myth of resources

It is quite common to hear things such as “former president Hugo Chávez benefited from oil at $100 a barrel, Maduro has had to deal with much leaner times”, “Maduro has been constantly suffocated by sanctions, Chávez had it easier,” etc. Such statements generally lack any quantitative data to substantiate them.

For this reason — and taking up Ellner’s request for empirical evidence — I want to look at oil production over the past 25 years (1999-2024), focusing on production and average prices, and comparing the Chávez period (1999-2012) with the Maduro period (2013-24).

I have relied on statistical data from the government’s Venezuelan Anti-Blockade Observatory — which in turn relies on monthly reports from the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) — and which, at least for now, remains publicly available.

If we analyse the period 1999-2012, we encounter some striking data. First, the average OPEC crude oil price during that period was far from $100 a barrel; rather it was $56.70. In fact, over that 13-year period, crude oil prices only exceeded the $100 mark in 26 separate months.

It was not until 2005 that average crude oil prices surpassed $50 a barrel. Yet, by then, the Chavez government had already initiated its major social missions in literacy and school education (Mission Robinson, Ribas and Sucre) and the Barrio Adentro social mission (providing primary level healthcare at the community level) was fully functioning. Several other important social programs were also in place — and all with oil prices well below $100 a barrel.

In terms of production, the average for this period was slightly more than 2.5 million barrels a day. It is true, as Terán noted in his article, that towards the end of Chávez’s period, production was trending downward. This was due to a series of factors that can only be summarised here, but whose nature were technical (migration from conventional oilfields off the eastern coast of Lake Maracaibo to unconventional oilfields in the Orinoco Oil Belt), operational (failures in project management) and financial (additional production costs).

During the Maduro period (2013-24), average crude oil production rose above 1.4 million barrels and the average crude oil price was $71. Yes, that is right — Maduro has, on average, benefitted from higher oil prices.

Many will say that just proves the impact of the sanctions; that despite higher prices, lower production and, in some cases, the discounts derived from sales made under conditions of the blockade made it more difficult to make the best use of these resources.

But, an extra fact should be considered: during the five-year period between 2013-18, average crude oil production was more than 2.1 million barrels a day and oil prices remained above $69 a barrel.

Curiously, during this same period we experienced the most severe process of labour market deregulation, public services were rendered largely useless, and social program coverage was greatly reduced. That is because, as noted above, foreign debt repayments were prioritised, despite imperialism’s threats.

Some will object, no doubt saying that Maduro had to deal with the guarimbas [violent street protests]. But they forget Chávez had to confront a coup attempt, an oil lockout, a kidnapping and assassination threats.

The issue is not simply one of economic problems but of political will.

The myth of the national capitalists

According to government spokespeople, there are two main sources for observing national private sector dynamics — the sector that will supposedly rescue the national economy. They are Conindustria’s Quarterly Survey of the Industrial Situation and the Venezuelan Finance Observatory’s (OVF) quarterly reports.

The former collects information on remuneration in the national industrial sector, while the latter mostly collects information on incomes for private sector workers in the Caracas metropolitan area, who are mostly employed in commerce and services.

In the national industrial sector, workers’ wages hit $235 dollars a month in the first quarter of 2025, a rise of 11.3% from the first quarter of 2024. This sum lags well behind the rise in domestic prices for goods produced by these industries (62.2%), as calculated by Conindustria.

The OVF’s data is also not encouraging. During the third quarter of 2024, the observatory recorded an average wage of about $241 dollars a month for those employed in the private sector in the Caracas metropolitan area. This is a rise of 7.1% from the first quarter, but below the observatory’s anticipated inflation (43%).

In fact, the private sector’s own data shows that, much like in the public sector, wages have suffered a prolonged and notorious fall in value. It is impossible, however, to measure precisely how this has affected the consumption of goods and services in real terms, mainly due to the lack of official statistics.

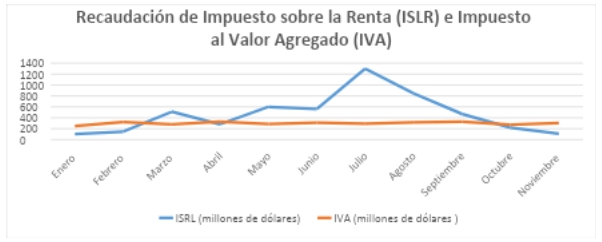

So, the best we can do is approximate via inference. One way is to take the Value Added Tax (VAT) as a reference for consumption patterns, noting it has remained constant at 16% and is imposed on all basic necessities, while accepting this will not be completely accurate due to tax evasion and commercial consumption. Nevertheless, it can at least provide us with some idea of the situation.

The graph above plots out two main sources of tax revenue: income tax (ISLR), which represented 45.8% of total tax revenue between January-November 2024; and VAT (IVA in Spanish), which represented 29.3%. As we can see, VAT revenue fluctuated slightly between $246 million dollars at its lowest point and $325 million at its peak. Average VAT revenue across this period was about $299.2 million a month.

Analysing VAT revenue, we can observe a flat trend when compared to the rise in ISLR revenue. This indicates that income growth has outpaced consumption growth. A partial conclusion we can draw is that most of the wealth produced is being concentrated in the hands of a few, rather than leading to higher consumption by the many.

These results may be partial, but one thing is certain: if wages are not keeping up with price rises, then consumption will decline. Many will object, pointing to the volume of remittances or the fact that US dollars are used to reinforce consumption.

However, generally speaking, any currency circulating in an economy is ultimately converted into capital, rent or wages. Regardless of the amount of money entering the economy, what ends up happening is that more will go to those who impose prices than those receiving lagging wages. Therefore, in the long term, consumption will tend to fall.

Applying a certain neoliberal logic, it can be argued that a needed transition from rent-based accumulation to industrial accumulation based on rising labour productivity and restraining real wages will, in the short term, lead to economic growth. If that is the case, then higher productivity should lead to a rise in available jobs.

Similarly, to make up for the lack of demand in the domestic market, we should see a rise in exports, as a means to reinforce the dynamism of the domestic market through a spillover effect. That is at least the vision of the technocrats in the Ministry of People’s Power for Economy and Finance.

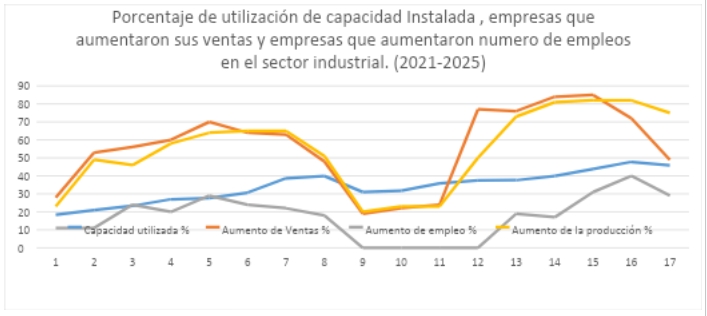

So, let us look at some data. Conindustria’s surveys between the first quarter of 2021 and the first quarter of 2025 show that, on average, 55.8% of companies acknowledged increasing their sales volume, 54.7% confirmed a rise in production, but only 22.6% confessed to increasing employee numbers.

In the graph above, we can see four indicators: capacity utilisation (blue), rise in sales (orange), rise in employment (grey) and rise in production (yellow). The graph tracks these indicators across the industrial sector over the past 17 quarters.

We can clearly see that job creation has lagged far behind the rise in the number of units produced and sold. Conindustria itself acknowledges that in those quarters where the number of jobs rose the most, the rise never exceeded an average of 1.5%.

So, we are strangely left with an industrial sector that produces and sells more, but falls well behind when it comes to generating jobs. This is despite raising capacity utilisation by more than 148% during those 17 quarters (from 18.4% at the start of 2021 to 45.8% in the first quarter of 2025). Contingently, we can deduce a steady rise in labour productivity, thanks to a rise in the intensity and duration of labour exploitation.

It is clear that the existing wage system, both private and public, is a long way from fulfilling its social function. Nor is there any correlation between social sacrifice and strengthening Venezuela’s industrial sector or economy more generally. It seems there are very few arguments to support the private sector alliance that is so celebrated by “pragmatic” sectors.

Let us now look at how the private sector has gone in terms of developing its so-called export vocation. In the first quarter of 2021, 85% of companies surveyed by Conindustria confessed to not exporting. By the second quarter of 2024, the percentage of companies exporting had risen, though most (about 62%) were still not exporting.

Also worth analysing in these surveys is the issue of imports. In the first quarter of 2021, 60% of companies relied on imports for their operations. By the second quarter of 2024, this had risen to 89%.

So, while the percentage of companies exporting rose by 23%, companies that were now importing rose by 29%. That is, imports grew quicker than exports — demonstrating that growth in the industrial sector is structurally dependent on external markets. As installed capacity utilisation rises, so does demand for foreign products, and with it the vital need for foreign currency to acquire these goods.

This is easy to verify by comparing the volume of non-oil exports in the private industrial sector with the sector’s demand for foreign currency. According to Venezuelan Association of Exporters president Gustavo González Velutini, exports for 2024 were below those of the previous year (totalling less than $3 billion).

But they were not only lower than exports for 2023, they were far below the $5.5 billion that the private sector acquired through interventions by the Central Bank of Venezuela (BCV) into the foreign currency market that year.

The real existing communal path

According to the latest data from the Ministry of Popular Power for Communes and Social Movements, there are 49,183 communal councils in Venezuela, of which only 30,219 form part of a commune. In turn, there are 3663 communes, of which, on average, less than 20% have functioning bodies, such as a communal government or bank.

One therefore has to ask: how can any communal project be carried out given such a low level of functioning bodies? How are projects being implemented? How are they being audited? How can a new democracy be built without a robust reinvigoration of such bodies?

Similarly, there are 4171 Social Property Companies (EPS). Of these, 3985 are directly communal-owned and 186 are indirectly communal-owned. This gives us an average of just over one EPS per commune, which falls well short of achieving what Chávez called the ”hegemony of social property”.

In more recent times, an alternative mechanism has been used to distribute resources to popular power: community consultations in communal circuits. Two consultations were held in 2024, and a further two more have been held so far this year. There is no doubt that this exercise has helped activate organising spaces and bodies within the commune; however, much more needs to be done.

But linked to the consultations is the question: why have no figures been given on participation levels in these consultations? Why are we simply told that “participation was massive”? Is this the right way to build a new democracy, or is it simply a means to eliminate what little democracy is left?

Can a digital register verifying participation be so dangerous? Would imperialism’s attacks become more intense if the Pentagon knew how many people voted in the consultation in a communal circuit in Santa Maria de Ipire?

Similarly, many of the projects that have been approved and executed, such as fixing roads or local public transport, fall within the competencies of municipal or state governments. Why not then push for the transfer of these competencies?

Why not demand that, as per Article 9 of the Regulations of the Organic Law of the Federal Council of Government, they be included in the list that needs to be submitted within the first 15 days of January by the relevant political-territorial entity, of proposed competencies to be transferred to popular power? A list, by the way, that since 2015 not one state or municipal entity has presented.

Then there is the issue of greater participation by the different forms of popular power in determining the use of the state’s extraordinary revenue streams, such as from oil and mining. Currently, 100% of resources allocated to the consultations, and its various bodies, come from VAT revenue that, strictly speaking, represent less than 3% of overall state revenue.

One final comment: up until June, the BCV had injected more than $2 billion dollars into the private foreign exchange market; in that same period, less than $200 million was allocated to financing communal projects.

This is a simple fact not rhetoric — and alone is enough to show the governing elite’s priorities.

Secrecy and new governance structures

Ellner will no doubt remember that in Chapter 6 of his book Rethinking Venezuelan Politics: Class, Conflict, and the Chávez Phenomenon, he discussed the differences between the soft and hardline currents within the Chavista movement, and above all the existing tensions between traditional and parallel political structures.

He must therefore understand that, in Venezuela today, we have the absolute colonisation of parallel structures by the traditional structures, and with this the complete closure of any transformative possibilities for popular power and constituent forces.

This contradiction has provoked debilitating conflicts between workers and the state, has led to a separation of the leaders from the masses, and facilitated the establishment of an authoritarian and bureaucratic system in which everything is sacrificed for the sake of production.

Economic decisions are made by the Higher Council of the Economy with no popular representation. Negotiations over our resources are carried out in secret and without any audits.

The democratic exercise of voting has become a fiction, far removed from what we had become accustomed to. The very defence of our rights and freedoms depends more on one’s ability to remain silent than one’s ability to fight.

It is worth here quoting Bolivian revolutionary Álvaro García Linera, who, referring to a revolution in progress, points out:

… there is the possibility of a social revolution in progress if the organisational modes of the action of the masses surpass the fossilised shell of representative democracy and invent new and more widespread modes of full participation of the people in the decision making on the common issues. There are socialist tendencies if the revolution generates mechanisms that exponentially increase the participation of the society in the debate, in the decisions that affect it; and, moreover, if these decisions are made in the collective, universal benefit of the society as a whole and not for individual or corporate revenue.

Today the field of politics appears closed to the great majorities, both in terms of their economic and social destinies. That is the problem we face.

The conditions that gave rise to the Chavista phenomenon remain intact: strong concentration of economic factors; exclusion of the vast majority from the national productive apparatus; a worn-out, corrupt and hermetic institutional framework; and, above all, a complete void between the governing elites and ordinary people.

Cuban revolutionary Orlando Borrego used to warn, when referring to leadership, that by advancing alone, leaders distance themselves from the rearguard, who are left behind. When no care is taken to maintain the needed relationship between leaders and the base that sustains them, the result is purely ephemeral triumphs.

In the July 28, 2024 presidential elections we witnessed, in part, a base rejecting its leadership that had left it behind. The leaders, however, decided to continue marching alone towards an ephemeral victory.

Returning to Sartre, today it is time to reflect on a new ghost, the ghost of Madurismo and the anti-popular, frivolous and cynical system that it conceals, but still seduces the unwary...

Dante Espinoza is a member of the National Commission of Comunes.