The causes of the Ukrainian crisis

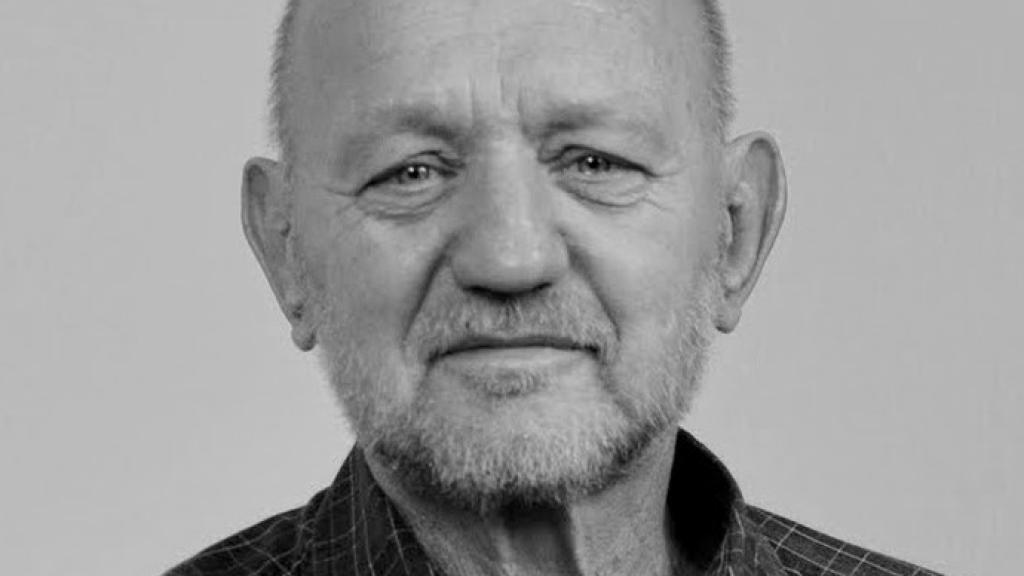

First published at Commons in 2016. Republished in memoriam of Marko Bojcun (1951-2023)

This article explores the origins of the Ukrainian crisis in several historical developments that came together in 2014. The first development, and the condition necessary for activating all the others, is the situation that has unfolded inside Ukraine itself since 1991 with the establishment of a new nation state simultaneously with the return of capitalism. The second is the isolation of Ukraine from the regional economic and security blocs of the Euro-Atlantic core states to the west and of Russia to the east. The third is the revival of Russian imperialism, and the fourth is the ensuing rivalry between Russian and European imperialisms to incorporate Ukraine into their respective transnational strategies. The fifth development is the overarching confrontation between a declining American power and a reviving Russian power in Europe. Russia is observed as the proactive power that militarised and internationalised the Ukrainian crisis in 2014 by seizing Crimea and arming the separatist insurgency in the east. It brought the question of European security to the centre ground, making a confrontation inevitable between Russia and the USA. However, it also has the potential to open up cracks in the Euro-Atlantic core between the USA on the one hand and the most powerful European states on the other.

The fragility of the Ukrainian state

The Maidan arose in 2013, as it did in 2004, because the new Ukrainian ruling class failed to share state power democratically or to invest in the development of its own society. Lacking democratic legitimacy or an adequate social consensus made the state weak and less capable of dealing with the challenges and opportunities it faced from neighbouring powers.

This past quarter century we have seen the simultaneous construction of a new nation state and its still incomplete transition to a capitalist economy. State building and the privatisation of the nationalised assets have been not only simultaneous, but also symbiotic processes. The state was built as the instrument for the wholesale transfer of these assets into the hands of a very narrow class that we call the oligarchs. The social class then turned the state to enabling new rounds of wealth accumulation from the living labour deployed in the growing private sector.

The old Stalinist bureaucracy was not driven out of the collapsing nationalised economy. Rather, it made its own way to the individual and corporate ownership of the economy’s “commanding heights”. So too did it ensure its own resurrection in the political sphere where it became the absolutely dominant subject of the multi-party system.

The state rested on a fragile social consensus of a population holding onto an ever fading promise that prosperity would come from leaving the Soviet Union and joining the West. The Ukrainian masses rose up in frustration and anger over this broken promise in 1994, 2001 and 2004 [1], but their increasingly massive protests failed each time to fundamentally change things. On the contrary, the Ukrainian people are poorer today as they were in the last year of the USSR, and they are riven by far more inequalities than they were then. Their influence over public policy and public institutions remains weak, even if they have managed repeatedly to recover their basic rights to free expression, assembly and self organisation.

Thus the present crisis is in the first instance attributable to the failure of a newly independent state to meet the mass expectations on which it was founded in 1991 The Maidan in the winter of 2013-14 was the latest revolt against this manifest failure, a mass movement that briefly undermined the new ruling class, drove its most powerful faction out of the country, but ultimately failed to dislodge it from the political and economic institutions. However, the Maidan was sufficiently threatening to compel the Russian state – gendarme of the transnational ruling class in its region – to intervene and seize Crimea, to arm a revanchist insurgency in the Donbas, and so to prevent the revolutionary process from spreading into the east and south.

The international isolation of the Ukrainian state

The second historical development that contributed to the outbreak of the current crisis was the failure of the Ukrainian state – for reasons not of its own making alone – to integrate successfully into either the Euro-Atlantic alliance or the Russia-led alliance. Its resulting isolation from the integration projects on either side made Ukraine particularly vulnerable to shifts in the relations between the big powers in the region.

After succeeding Leonid Kravchuk as president in 1994, Leonid Kuchma pursued a strategy to build a national ruling class that could hold its own place in the international political economy. His strategy required keeping Western and Russian capital out of the first big privatisations of nationalised property, accumulating wealth at home and upgrading technologically so as to prepare the country for membership in the EU and its single market. Kuchma’s strategy failed because the state leadership could not compel its own capitalists to keep their wealth in the country to upgrade and diversify the domestic economy. Rather, Ukraine became a low wage, energy and materials intensive exporter of primary goods and semi finished products in agriculture, energy, chemicals and minerals, the profits from which the oligarchs sent abroad. [2]

There was a rapid rate of economic recovery on the back of growing exports. However, the concomitant recovery in wages and services was strikingly uneven across the regions, with average wages in the east rising to 700 hryvnia by mid 2004, against 500 in the west of the country. The mounting social and regional economic inequalities and an increasingly repressive regime were the triggers for the 2004 Orange Revolution.

From Kuchma’s second term in office and Putin’s first in Russia, Russian capitalists succeeded in placing substantial investments in the Ukrainian economy. Kuchma’s successor in 2004, Viktor Yushchenko, tried to offset the Russian advance by inviting in European investment capital. By 2008 the Ukrainian economy was well penetrated by both Western and Russian investors, neither of whom contributed much to diversifying or upgrading it. Rather, each side was trying to incorporate Ukraine’s natural resources, cheap labour and its markets onto a low technological echelon of its own regional chains of production and consumption.

Yet the 2008 financial crisis prevented either side from making a bid for a dominant position. The Ukrainian oligarchs still held onto their hope of remaining an independent capitalist class in the global political economy. They resisted incorporation into the succession of Russia-led integration projects: the Commonwealth of Independent States and the Customs Union. The European Union, on the other hand, did not want them in as members – and made that abundantly clear in 2005-7 by rejecting the requests for a membership path from Yushchenko, the most pro-Western of all Ukraine’s leaders. Moreover, the EU’s biggest states – Germany, France and Italy – remained steadfastly opposed to offering Ukraine membership in NATO.

So Ukraine ended up in the grey zone between US-led Europe and Russia, and the likely recipient of friction between them that grew as Russia revived and US influence in Europe waned.

The revival of Russian imperialism

The third historical development contributing to the current crisis has been the revival of Russian imperialist ambitions. Throughout the 1990s the Western powers set the agenda, incorporating Central European and Baltic states into the EU and NATO, and all the time holding Russia, Ukraine and Belarus at arm’s length outside their integration project.

From around 2000 Putin began to restore Russia’s position as a power in Eurasia. He focussed first on rebuilding Russia’s economic ties in the ex-Soviet space by reclaiming state control over Russian energy and mineral resources and promoting several national corporate champions in these sectors. Later, the restored economic links with Russia’s near abroad would lay a path to securing transnational competitive status for Russia’s biggest energy and mineral producers. [3]

In terms of strategy, though not of scale, the Russian model of imperialism is similar to that of the USA in the 20th century: the provision of military security to countries in exchange for their alignment with Russian foreign policy, and their access to Russian markets in exchange for the removal of barriers against Russian capital penetrating their national economies. It is different from the USA experience insofar as Russian expansion has relied on its competitive advantages in global markets of fuel, energy and mineral resources whereas American capitalism expanded globally with a far more diversified production base and with already saturated domestic demand.

The Russian economy is weakly driven by domestic demand, and it does not satisfy it. It is not diversified nor is its bourgeoisie willing to invest significantly in its diversification. Property ownership in Russia is too insecure, access to domestic resources and markets is in the gift of state authorities, and better security and better investment opportunities exist for Russian capital investment abroad. Therefore, while the Russian national economy is not diversified, Russian capital has become diversified both sectorally and geographically along transnational chains of production, trade and investment.

A Deutsche Bank report in 2008 concluded that Russia had become by 2006 the largest outward investor of its capital of all the BRIC countries. Russian overseas direct investment (ODI) was double that of its nearest rivals India and China at USD$160 bn, up from USD$20bn in 2000. Russia was already the second largest source of ODI in emerging markets after Hong Kong. Russian private capital was invested first in the near abroad and then expanded outwards, seeking new markets, financing and new technologies principally in the fields of fuel, energy and metals

A survey of 25 top Russian firms shows they sent 52% of the ODI into Western Europe, followed by 22% to the near abroad countries and 11% to Eastern Europe. Several Russian companies, including Evraz, Severstal, Lukoil and Gazprom, made new large purchases abroad in 2008: in Ukraine, Belarus, Italy, Canada and the United States. At The other big transnational corporations of Russian origin at the time were Sistema, Sovkomflot, Norilsk Nickel and Basic Element. By 2010 ODI by Russian firms exceeded USD$200bn, and was going mainly to the CIS and EU countries. [4]

For the past fifteen years Russia has targeted Ukraine for reabsorption into its traditional sphere of influence. There was an ongoing desire to preserve joint production in engineering, defense, aerospace and other high technology sectors that survived the Soviet break-up. But Russian capitalism was looking to new horizons as well, and Ukraine lay along its principal path of expansion into Central and Western Europe. It holds the downstream transit facilities and processing industries that Russian energy, minerals and chemical producers need. Russian producers made their first such cross border acquisitions in 2000. [5]

But the gas and oil transit pipelines through Ukraine that link Russian suppliers to European consumers, the most valuable transit facility of them all, has remained steadfastly in state hands.

The Yanukovych presidency

The period of Viktor Yanukovych’s presidency saw further popular alienation from the political order, the economy falter under the blows of the 2008 financial crisis, and the state face a zero-sum choice to accept either Russia’s or the West’s terms of integration into their respective regional integration projects. The mixture of these three factors finally exploded in Kyiv in the winter of 2013-14.

Yanukovych narrowly defeated Yuliya Tymoshenko for the presidency in 2009 on a platform of political stability and the restoration of economic ties with Russia. [6]

His predecessor Yushchenko had fallen out bitterly with Tymoshenko as Prime Minister over policy towards Russia. Tymoshenko took the full force the 2008 financial crisis. She negotiated for emergency funding with the IMF in 2009. Ukraine-Russia relations were dominated by disputes about the cost of Russian gas and for its transit to Europe. The state corporation Naftogaz Ukrainy became more and more indebted to Gazprom, and the Russian government used the debt to pressure Ukraine on a variety of issues.

Yushchenko had tried to balance growing Russian economic penetration by opening up the country to Western investment. That influx ended spectacularly with the financial meltdown in 2008 that battered people’s livelihoods and convinced enough voters, even in the nationalist west of the country, to give Yanukovych a chance to turn things around. The arrival of Armani-dressed oligarchs in window darkened limos with bodyguards to Yanukovych’s inauguration in Kyiv in January 2010 gave everyone a taste of things to come.

Yanukovych perfected the scheme of taking bribes from all businesses his ministries permitted to trade. These appropriations made him a tycoon in his own right (he was nominally represented in the private sector by his son Oleksandr. Yanukovych created his inner circle, called “the Family” from the seven most powerful capitalists. He restored Dmytro Firtash, the gas trader, to financial health by giving him 12 billion cubic metres of Russian gas in settlement of a dispute Firtash’s firm Rosukrenergo had had with Naftogaz Ukrainy during Yushchenko and Tymoshenko’s terms, when they tried to close him down. Rosukrenergo once again became the intermediary between Gazprom and Naftogaz Ukrainy in a scheme that allowed Russian and Ukrainian presidents and oligarchs to milk the interstate gas transit. Gazprom opened an $11bn credit line for Firtash, which he used to build a monopoly stake in fertilizer processing in Ukraine, a port facility, a bank and the national television channel Inter. [7]

Rinat Akhmetov, the country’s richest man, was also blessed when Yanukovych granted his firm DTEK the monopoly to export electricity. He also ordered the state energy regulator to increase tariffs local and regional authorities paid for DTEK’s electricity from coal burning stations to levels comparable to those paid to state operated nuclear power stations. Both Akhmetov and Firtash won tenders to privatise regional electricity distributors. Both placed their representatives into the state energy regulating commission to ensure they continued to get high returns for their gas and electricity. [8]

In November 2012 President Yanukovych signed a Double Tax Treaty with the government of Cyprus to replace the Soviet era treaty. Thus he preserved the channel used by the biggest corporations to expatriate their profits either permanently or to recycle them back to Ukraine as foreign investments and loans that were subject to much lower levels of capital gains tax. Flight of capital to tax havens was taking place through various other channels used by Ukrainian and foreign firms alike. They consistently deprived the state budget of between $10bn and $20bn every year. [9]

As soon as he took office Yanukovych moved to strengthen presidential authority over the legislature, judiciary, public procuracy and the Kyiv city government. The rules were changed to make it easier for the Party of Regions to build voting majorities in the Verkhovna Rada. And in August 2012 the law by which the Rada was elected entirely on the basis of proportional representation of parties was replaced. Now half the seats would be chosen on the basis of proportional representation of those parties that gained more than 5 percent of all votes, and the other half by single mandate constituency elections. The new law gave the President’s Party of Regions a way to finance its own candidates disguised as independents to run in the single mandate constituencies. It also provided the means to subvert the democratic oversight of local electoral committees and to deliver fraudulent vote counts to the Central Election Commissions.

The October 2012 elections to Verkhovna Rada were the dirtiest since the falsified presidential elections in 2004 that provoked the Orange Revolution. They provided Yanukovych with a majority of deputies in the Rada, elected by proportional representation from the list of the Party of Regions and as nominally independent candidates standing in single member constituencies. [10]

In addition to settling scores with potent rivals, the imprisonment of Yulia Tymoshenko and Yuriy Lutsenko (former Minister of Interior) and their barring from public office for 7 years served to intimidate the parliamentary and extra-parliamentary opposition. State security organs went after opposition candidates, independent analysts, university rectors and investigative journalists. A attempt was made – in the end unsuccessful – to muzzle the media by making slander of public officials a criminal offense. This broader offensive had some of the hallmarks of the drive to “sovereign democracy” made by Putin years before in neighbouring Russia.

The economy

Economic growth in the period 2000-2008 were driven by the influx of foreign direct investment into domestic retail markets and the commodities that dominated Ukraine’s exports: raw and semi-processed minerals, chemicals and food products. When their hugely inflated prices finally collapsed in 2008 GDP dropped more than 15% in the following year, the second deepest fall in Eastern Europe after Latvia. The combined private sector and public sector debt mounted to $103 billion, or 88% of the country’s 2008 GDP. [11]

Commodity prices recovered at the end of 2009, but in the longer term international demand did not. Ukraine’s recorded annual GDP grew again, in 2011 by just over 5%, but then fell back and registered no growth at all in 2012 and 2013. In 2014 it began to contract as a result of several factors: continued weakness of external demand, massive capital flight, the Russian seizure of Crimea and the war in the east of the country.

Trade

Ukraine’s foreign trade was characterised by the following patterns:

The value of its trade with the EU single market and with Russia has fluctuated over the years. The general pattern was the steady displacement of Russia as Ukraine’s dominant trade partner by other countries. On the eve of the crisis the EU and Russia each accounted for around one third of Ukraine’s total trade. In 2014, as a result of the Russia trade embargoes against Ukraine’s exports and the Ukrainian government’s prohibition of trade in defense sector goods, the Russian share declined to around 21%, while the EU share rose to 35%.

Ukraine has incurred annual trade deficits in its trade with Russia as a result of its reliance on Russia’s and (transited through Russia) Turkmenistan’s oil and gas;

Ukraine has incurred annual trade deficits with the EU as a result of the disparity between the capital content of goods it imported from the EU (machinery, consumer durables) and those it exported to the EU (primary and semi-processed goods);

Ukraine has covered its trade deficits with Russia and the EU by generating surpluses from trade with the East Asian, Middle Eastern and African countries.

External trade remained in balance or went into surplus as long as demand for the country’s principal exports remained strong – i.e. between 2000 and 2008. Thereafter, the trade deficit grew year on year, reaching $15bn in 2012. [12] [13]

In 2013 Russia began a trade war with Ukraine in response to the first easing of trade barriers between the EU and Ukraine ahead of the anticipated free trade area agreement between them. Russia claimed that EU exporters would use Ukraine to dump their products into the Russian market. It banned imports of Ukrainian dairy products, fruit, vegetables, meat, sunflower oil and alcohol.

Investment

Annual foreign direct investment leapt forward after the Orange revolution from $1.7bn in 2004 to a peak of $9.2bn in 2007. Ukraine was second only to China in these years in terms of per capita investment flowing into the country. [14] For the first time much of this inflow came through the banking system, with many foreign banks setting up Ukrainian subsidiaries to provide both corporate lending and retail services. Most FDI went into export credits for agricultural and mining concerns, consumer lending, real estate and the domestic trade in imported luxury goods. [15]

The proportion of foreign capital held in Ukraine’s banks grew from 13% to over 50% between 2004 and 2008. Between them the banks of six EU member states held 30% of the banking capital. Financial institutions based in Russia held another 10%. The European share was held overwhelmingly by large commercial banks, headed up by Raiffeisen of Austria, Unicredit and Intesa San Paolo of Italy, and BNP Paribas of France. The Russian share was distinguished by the predominance of state banks among their holders – VTB, Vneshekonombank, Sberbank, BM Bank and Prominvestbank, and by four other banks tied to the Kremlin. [16]

The international financial crisis in 2008 forced the rival centres of foreign capital alter their positions in the Ukrainian market. Facing serious problems at home, the banks which had bought up the domestic networks of several Ukrainian banks were forced to sell. Ukrainian oligarchs, who had sold their banks at lucrative multiples of their book value now bought them back at a good discount. Russian banks, on the other hand, were better protected from the financial crisis by ample credit from their own government’s sovereign funds, so they strengthened their position in the Ukrainian banking system. On balance, however, the biggest initial winners were the Ukrainian private banks, which increased their share of assets in the banking system from 40 to 51% between 2008 and 2012. The Ukrainian state banks Oshchadbank and Ukrexsimbank also increased their share from 11 to 15% over the same period. [17]

The overall share of banking capital owned by foreigners fell to 34% in 2014. The share of Russian capital rose to 12%, making it the largest bloc from any one country and double that of its closest rival, Cyprus, at 6%. Not to be overlooked was the fact that a considerable share of Cyprus exported capital came originally from Russia. After fifteen years of cross border investment Russian capital was deeply penetrated not only into Ukraine’s banking services, but critically also in the processing and manufacturing sectors: petrochemicals, agrochemicals, food production, paper, construction materials, steel, non-ferrous metals, machinery and weapons manufacturing. It also had developed strong positions in mass media, telecommunications, insurance, business information and information technology. [18]

Debt

Ukraine’s state debt (including state guaranteed debt of the private sector) grew only marginally between 2000 and 2007 to $18 bn, or 12% of its GDP. Thereafter it grew rapidly, peaking at $73 bn in 2013. The country’s gross external debt, which included that of the private sector, was double that amount at $142.5bn, equivalent to 78.3% of GDP in 2013. [19]

Tymoshenko’s government had taken $3.4 bn in IMF special drawing rights (stand by loan) in August 2008 to bail out the country’s banks and repay sovereign debt for Russian gas imports. Yanukovych’s government led by Premier Mykola Azarov was responsible for adding another $40bn to the state debt over four years, including: $20 bn in treasury bills and Eurobonds; $6.85bn in IMF Special Drawing Rights in August 2010 and April 2013; $6.6bn borrowed from the Chinese government in 2012; and $3bn of the $15 bn originally offered by the Russian government in November 2013 to help persuade Yanukovych not to sign the Association and Free Trade Area Agreements with the EU. [20] The Ukrainian government was additionally in arrears to Gazprom for several billions dollars’ worth of gas. [21]

Debt repayment became an increasingly heavy burden on the state budget, at the end of 2014 accounting for 40% of total expenditures. [22]

For both the West and Russia Ukraine’s indebtedness provided a handy lever to influence its government. The IMF was the arbiter of its creditworthiness and so its gatekeeper to international capital markets It tried to impose its conditions on the government to decrease state ownership of public utilities, and to withdraw subsidies on the cost of supplying them to households, communal services and to businesses.

The Russian government used Ukraine’s indebtedness and its dependence on Russian export markets to lever the Kharkiv Accords in April 2010. The Accords extended the lease of Sevastopol and other Crimean ports to the Russian navy until 2042 in exchange for cheaper gas. In June of that year the Verkhovna Rada excluded the goal of NATO membership from the country’s national security strategy, thus restoring its a non-aligned status. Yanukovych also agreed to start talks with Russia about merging the state utility Naftogaz Ukrayiny with Gazprom and deepening co-operation between the countries’ defence, aerospace and aeronautical industries.

Labour migration

The movement of labour also reveals the pattern of Ukraine’s incorporation into the international political economy. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union Ukraine has exported its labour in two directions: workers living in the east of the country have gone largely into Russia, while those in the centre and west have gone into the EU countries. They number in the millions, and their outmigration has had a profound, if the contradictory impact on the Ukrainian economy. It has lost skilled and well-educated people to countries where they are now employed as cheap, illegal or legally precarious labour. Communities depopulated by the outmigration have seen their social and family structures severely degraded. Migrant workers have been sending remittances from their earnings home that are estimated to exceed the combined foreign direct investment coming into Ukraine. [23]

Without their remittances, the condition of the working class would be considerably worse than it is today. The overall impact of labour outmigration, however, has been negative as far as the reproductive capacity of Ukrainian society is concerned.

The zero-sum choice

Labour migration, trade, the repatriation of profits from FDI, debt repayments and capital flight are all tributaries for the extraction of wealth from the Ukrainian economy. The European Union and the Eurasian Economic Union are both regional integration projects designed to comprehensively regulate and channel such tributaries into their respective metropolitan cores. In 2013 the Ukrainian state found itself forced to choose between the EU on the one hand and Customs Union on the other. The Customs Union, formed in 2010 and made up of Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan, was the precursor to the Eurasian Economic Union. The latter was launched in January 2015, together with Armenia as its fourth member. This was a zero-sum choice because there was no way for Ukraine to belong to both regional integration projects. The fact that its economy was closely tied to both the Russian and EU markets, asymmetrically but nevertheless in equally strong measures – through debt to the West, energy supplies from the east, and trade with both – was simply ignored by Russian and EU leaders.

The European Union and Ukraine had a Partnership and Co-operation Agreement since 1994. They had been negotiating since 2007 an Association Agreement and a common “deep” free trade area based on the laws, state competition policy and production standards that are already enforced within the EU single market. These requirements, which the Verkhovna Rada was urgently adopting throughout 2013, would add considerable costs to the state and the private sector in order to make Ukrainian goods acceptable in the EU market. Except for a transition period when EU food products and Ukrainian automobiles were protected from competition, the abolition of almost all tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade would in the long run expose several Ukrainian industries to sustained and ruinous competition from the EU side. [24]

Moreover, the EU’s offer was “integration without the institutions”: Ukraine was not offered membership in the EU nor even the prospect of membership, so it would remain excluded from the decision making process that shapes the EU single market in which its own businesses and workers were going to compete. It was not an attractive proposition.

The Customs Union and its successor Eurasian Economic Union offered Ukraine something different. This integration project was far less developed than the European Union’s. Russia accounted for 90% of the combined GDP of the Customs Union’s members, which meant that Russia would dominate the Union whatever its formal governing structure. The Russian establishment saw in this project one of the important means to reclaim great power status. The news agency Sputnik hailed the launch of the Eurasian Economic Union in January 2015 as “the birth of a new giant”. Putin called it “a powerful supranational association capable of becoming one of the poles in the modern world and serving as an efficient bridge between Europe and the dynamic Asia-Pacific region.” [25]

But such a bridge was hardly possible to build without Ukraine. Russian diplomacy focussed on this challenge, trying to coax it into the Union by promising generous energy subsidies if it joined and trade sanctions if it didn’t. But even under Yanukovych and in the worsened economic situation the government continued to resist. There was a fundamental lack of trust between Kyiv and Moscow, at its heart of which was the refusal of the Russian state to acknowledge Ukraine’s independence. [26] This refusal is rooted in a long history of Russian imperial domination of Ukraine. It is justified ideologically by the claim that the Ukrainian nation does not exist, that its people are simply the “little brothers” of the Russian nation (malorosy). After gaining independence in 1991 Ukrainian leaders regularly faced jibes from their Russian counterparts about when they would finally come to their senses and stop playing their game of nation building. Putin expressed perfectly the paradox that Ukrainian statehood poses to Russia’s leaders when he told George W Bush in April 2008 at the NATO summit in Bucharest that Ukraine really wasn’t a state, but if it tried to join NATO it would cease to exist as a state. [27]

It was therefore hardly surprising Kyiv baulked at pooling its sovereignty with Russia’s in the Customs Union or the Eurasian Economic Union.

Despite the Kharkiv Accords lowering the price for Russian gas by $100 per thousand cubic metres (tcm), Ukraine continued to pay more than Germany and Italy, which are considerably further from Russian gas fields than Ukraine. Neighbouring Belarus enjoyed a lower price, but only after its president Alexander Lukashenko sold the country’s gas transit pipelines to Gazprom. The Ukrainians were not ready to do that; instead, they began to diversify their sources of supply, reducing imports from Russia from 57 million cubic metres (mcm) in 2007 to 33mcm in 2012 and 26mcm in 2013. [28]

The Ukrainian government’s inability to service its foreign debt brought matters to a head at the beginning of winter in 2013. Putin and Yanukovych held talks in Moscow on 22 November 2013 after which Yanukovych announced he would not sign the Association Agreement and the linked European Free Trade Agreement at the upcoming Summit of the EU Eastern Partnerhip in Vilnius. When the news reached Kyiv several hundred people gathered on the Maidan to protest and demand Yanukovych sign the agreements.

In Vilnius on 29 November he said at his press conference: “We have big difficulties with Moscow. I have been alone for three and a half years in very unequal conditions with Russia”. [29]

He proposed as a way out of the situation that Moscow be involved in three way negotiations with the EU and Ukraine. But EU officials rejected his proposal.

Addressing the Eastern Partnership’s plenary session Yanukovych insisted he was not rejecting the Agreements, but wanted further negotiations in order “to minimise the negative consequences of the initial period that will be felt by the most vulnerable groups of Ukrainians”:

“Unfortunately Ukraine has been left facing serious financial and economic problems recently….(we need) macro-financial assistance…the restoration of co-operation with the IMF and WB…a revision of trade restrictions on individual items…participation of the EU and international financial institutions in the modernisation of the Ukrainian gas transit system…as the key element…to ensuring Ukraine’s energy independence…the elimination of contradictions and the settlement of problems in trade and economic cooperation with Russia and other members of the Customs Union related to the establishment of the free trade area between Ukraine and the EU”. [30]

Yanukovych was being pressed to choose between Russia and the West, but he wanted co-operation with both sides to deal with the country’s mounting problems.

The Maidan

By the time Yanukovych uttered these words, the protesters on Kyiv’s Maidan had grown to several thousand. No-one was paying attention to the very real shortcomings of the Agreements. Or that the EU was not prepared to offer more than 10m euros to help the government service a debt in the billions. [31]

The protesters simply saw in Yanukovych’s refusal to sign the Agreements a rejection of the EU as a result of the pressure coming from Moscow. In the night of 29-30 November students camping on the Maidan were brutally beaten by riot police and dozens of them were imprisoned. Their treatment caused outrage in the capital and the numbers on the Maidan the following day, 1 December, swelled to hundreds thousand.

The Ukrainian crisis internationalised

The events which then unfolded in December, January and February and became known around the world as “the Maidan” constituted a mass struggle to overthrow the political regime of Viktor Yanukovych. Although he was removed from power, the class of oligarchs whose power and interests his regime served was not removed. Rather it was split, with the rump of Yanukovych’s faction among the class of oligarchs driven to the eastern border where it mounted its revanche in the form of a separatist movement against those oligarchs who retained control over the state institutions in Kyiv. Crucially, the Maidan failed in several respects to utilise the revolutionary potential of this historical moment. It failed to drive the oligarchs from the institutions of the state, to challenge their control over the economy, or to offer an alternative programme of social and economic development.

However, the outcome of the struggle between the Yanukovych regime and the Maidan – with the class of oligarchs increasingly divided between them – was not resolved solely on the basis of domestic forces alone. If not at the beginning of the mass mobilisations then certainly by the end of the regime both Russia and the United States of America strived to influence the course of events to their own great power advantage. However, it was Russia that decisively turned the struggle for power inside Ukraine into an international crisis. As Yanukovych’s position in Kyiv grew more tenuous the Russian leadership deployed military forces to its border with Ukraine and reinforced its positions in the leased Crimean naval bases. After Yanukovych fled Kyiv Russian forces began taking control of the Crimean government, the peninsula’s communications and the urban centres, and lay siege to Ukrainian military bases there.

By seizing Crimea Russia violated the Budapest Declaration, which it signed along with the USA and the UK in 1994. In exchange for Ukraine giving up its nuclear weapons – which were sent to Russia, no less – the signatories had promised to respect Ukraine’s territorial integrity and national sovereignty. Russia also violated the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Partnership it had signed with Ukraine in 1998. It violated the UN Charter by changing international borders by force, offering as its only defense the fact that the Western powers had done the same by upholding the separation of the Kosovan statelet from Serbia. Putin acknowledged much later he ordered the occupation and annexation of Crimea. [32] And the Russian FSB agent Igor Girkin-Strelkov, who served in Crimea at the time before being dispatched to the Donbas [33], described on the NeuroMir tv channel how Russian armed forces, and not the local authorities, organised the so-called referendum. [34] Putin’s plans were far more ambitious than what he actually achieved. [35]

According to the Moscow based newspaper Novaya gazeta eight oblasts were targeted for separation from Ukraine. If successful, this would have given Russia a land bridge from its western border through to Crimea and across to Transdnistria, thereby cutting Ukraine off completely from the Black Sea. In the end, Russian and Russia-backed Ukrainian forces took only parts of two oblasts, Donetsk and Luhansk. Initially they made up about 4% of the territory of Ukraine in 2014, and 5% after the separatist offensive in January 2015, but they accounted for a considerably larger portion of its GDP and export earnings.

The separatist movement was launched by members of Yanukovych’s Party of Regions when it became clear their power in Kyiv was broken. Rinat Akhmetov, a prime beneficiary of Yanukovych’s patronage whose businesses are concentrated in the Donbas, provided the initial finance for its armed detachments. [36] The separatists’ declared aim was to protect the region’s Russian speakers from Ukrainian “fascists and banderites” allegedly coming from Kyiv to ethnically cleanse them. [37]

But their real aim was to prevent the spread of the Maidan into the east where the oligarchs’ industrial assets and power were concentrated. The ousted fragment of the oligarchic regime clung to this separatist platform in the east and started to rock it so as to upend the Kyiv government.

The separatists were reinforced by Russian nationalists, fascists, mercenaries and soldiers “on leave” from across the Russian border. Russian nationals took over the leadership of the Donetsk People’s Republic (Aleksandr Borodai) and its Slovyansk military headquarters (Igor Girkin-Streltsov), sidelining the original Ukrainian leader (Pavel Gubarev, a former member of the neo-Nazi Russian National Unity). [38]

As the Kyiv government stepped up its military campaign against these militias and their declared republics Russia increased both the calibre and supply of personnel and weaponry to them. The so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics did establish a certain social base and a professional cadre drawn from the region itself. But their military, diplomatic and financial capacities were almost entirely dependent on the Kremlin.

Russia’s principal motive in seizing Crimea and backing the separatist movement in the east was not to gain territory, but above all to suppress the Maidan and to restore Russia’s influence over the government in Kyiv that Yanukovych had previously guaranteed. The Maidan threatened Russia’s interests not only in Ukraine: it showed that oligarchic-capitalist states in the region could be overthrown by a sustained popular uprising.

Russia aimed to prevent Ukraine’s further incorporation into the Atlantic alliance through an association agreement or a free trade regime with the EU or a path to NATO membership. It was alarmed at the economic consequences for itself of an EU-Ukraine free trade regime and at the possibility the EU association agreement might become a back door for Ukraine to get into NATO. It sought guarantees for Russian capitalists’ access to Ukraine’s markets and their protection from competition by EU investors and producers. It wanted a government in Kyiv that would instead align its economic and security policies with Russian regional and global strategies, that would eventually join the Eurasian Economic Union and a Russia-led security alliance.

Russia’s timing and calculations

Why did Russia choose this moment to seize Crimea and intervene into the eastern oblasts? Russia was weaker militarily than the USA, but only in an abstract comparative sense. In the real disposition of their conventional forces Russia was stronger than NATO in its own near broad. Its immediate neighbours were militarily weak and NATO was unable to project and sustain its power in the region. It could not fulfil its commitments to mutual defence of members in Eastern Europe for strictly logistical reasons – it had no forward bases there of any significance and could not establish them quickly. As the Estonian defence minister Sven Mikser put it on 24 June 2015 “Putin believes that he enjoys regional superiority”. [39]

Most important to Putin’s calculations were the political divisions between the USA and its European allies over relations with Russia. According to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center the leaders of Germany, France and Italy were not prepared to come to the defence of East European member states like Latvia, Lithuania or Estonia if they were attacked by Russia. [40]

And there was a growing resistance among the American public to more military campaigns abroad which placed real restraints on the American administration.

All these factors emboldened Russia to intervene in Ukraine at the moment of opportunity, for which it had been preparing. Russia was rebuilding its military capabilities and placing them forward across its own borders. After the Soviet Union’s collapse, the Russian Federation held onto military bases in Belarus, Transdnistria in Moldova, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Kazakhstan. After Putin became president, they were augmented with new bases and additional forces in existing ones in Belarus, Armenia, Georgia and Ukraine. In 2014 after annexing Crimea Moscow annulled its previous agreements with Ukraine on its bases at Sevastopol, Kerch and other Crimean locations. In January 2015 the Russian defence ministry issued a new military doctrine and announced plans to spend 20 tn roubles ($310 bn) by 2020 to upgrade its military capabilities in Crimea, Kaliningrad and the Arctic. [41]

Into the arms of the western powers

If Putin’s aim was to dissuade the Ukrainian state from seeking closer ties with NATO then his actions had the opposite effect. The Verkhovna Rada revoked the country’s non-aligned status and urged the government to seek NATO membership again. The government sought lethal military equipment from NATO, which was refused. And the attitude of the population towards NATO membership made a historic shift from a majority consistently opposed since 1991 towards a majority in favour [42]. And throughout this period the official position of NATO states, including the USA, was no more than stating Ukraine had a right to seek NATO membership and to actively dissuade any such application. This was their response in a period when Russia stepped up deliveries of heavy weapons to the separatists (including the BUK missiles that shot down Malaysian passenger airliner MH17) and sent in its own trainers and political advisors, helping them to halt the Ukrainian offensive in the summer of 2014, return to the offensive themselves and take more territory and population. Poroshenko walked away from the NATO summit in Wales in August 2014 without the weapons he’d asked for [43]. And then he was obliged by his Western allies to send ex President Kuchma to negotiate the Minsk Accords in September with the leaders of the separatist republics, by which they were recognised as parties to an interstate agreement.

So what is the evidence in 2013 and 2014 that it was NATO encroaching further into Russia’s “traditional sphere of influence” which provoked Putin to react by intervening militarily into Ukraine? The available evidence suggests otherwise: Putin was the proactive side in confrontation that ensued. He calculated correctly that NATO would not respond in kind to Russia’s attack on Ukraine if that attack was decisive and rapidly attained its objectives.

In part, that is what happened, at least with regard to the Crimea. The Western powers take it as a fait accompli. However, the ongoing crisis did not play out like the Russia-Georgia shooting war that lasted for only four days in August 2008. Putin miscalculated on the readiness of Ukrainian government forces to resist the separatist insurgency in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts and to suppress his efforts to widen it to the other oblasts. Putin had planned a rapid advance deep into the country. He failed to achieve that depth of position and the pro-Russia separatist forces were contained in the eastern reaches of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts. The Russians’ advantages in speed and geographic proximity diminished as the conflict dragged on, leaving them with superiority only in fire power. The war of movement became a war of position. And the longer it dragged on the more it encouraged NATO member states in the region to seek reinforcements of their own borders with Russia from their Western allies.

The balance of power

Framing the Ukrainian crisis is the changing balance of power between Russia, the USA and Germany as the leading EU state. Russia’s economic and military expansion places it on a collision course with US hegemony over Western and Central Europe. This collision is all the more destabilising the weaker becomes the USA’s capacity to project its own power into Eastern Europe.

As noted above Russian capital is investing and diversifying its portfolios in Western and Central Europe, and its government has long sought and secured bilateral co-operation with separate EU member states. It has done so deliberately to avoid negotiating with the EU as their collective representative. Germany is the most important such partner for Russia. It has the biggest investment in Russia of any country in the world, and Germany has admitted significant Russian inward investment in return. Corresponding to that mutual economic relationship there was a political axis of EU (Berlin)-Kyiv-Moscow in the making when the Ukrainian crisis broke open. The imposition a Western sanctions against Russia has created huge uncertainty as to its future.

This axis passes through a specific faction of the ruling class in Ukraine grouped around the tycoon and key Russian point of contact Dmytro Firtash, his ally Serhiy Lyovochkin, former head of Yanukovych’s presidential administration, and the Opposition Bloc in the Ukrainian parliament. This group is trying to build an EU-Kyiv-Moscow axis to compete with the existing Washington-Kyiv-Moscow axis. Their international platform to build this axis is the Agency for Modernisation of Ukraine, created in Vienna in March 2015. Its European participants include a range of prominent public figures. [44]

Its two main pillars of support in Ukraine are the Employers Federation, headed by Firtash himself, whose members’ businesses accounted for 70% of the country’s GDP in 2014, and the leadership of the Federation of Trade Unions. The faction of Firtash, Lyovochkin and the Opposition Bloc has been preparing to challenge the current government. The likelihood they will do so depends on at least two things: whether Poroshenko and Yatseniuk succeed in crushing Firtash first by destroying his business empire ( as part of the current campaign to “deoligarchise” of the state), and whether the Western powers and Russia agree between themselves that the current Ukrainian leadership needs replacing in order to impose a settlement to the war onto all sides.

The second political axis passing through the Ukrainian ruling class is a Washington-Kyiv-Moscow axis, which in Kyiv passes through the Poroshenko-Yatseniuk faction. This faction has been trying hard to discipline the biggest oligarchs Rinat Akhmetov, Ihor Kolomoisky and Dmytro Firtash to its pro-Western course . But all three oligarchs have powerful interests in maintaining ties with both Russia and the EU states. And this political axis does not have as powerful an economic chain at its foundation as the EU (Germany)-Kyiv-Moscow one has because the USA does not have a vital economic relationship with either Russia or Ukraine. Rather, its main underlying motive is to demarcate and discipline the European region over which the USA exercises hegemony. The war between Russia and Ukraine has become the issue through which Washington tries contain German ambitions and marshals all its European allies to oppose Russia, rather than to allowing them to work out deals with Russia behind the USA’s back. The USA’s approach is fundamentally different from Germany’s, which is to get Russia to uphold a common rules-based regional order that is also economically productive for both of them. Has the Ukrainian crisis, then, become a lightning rod for the further bifurcation within the Western alliance that places Germany on a tightrope between the USA and Russia?

Conclusions

I have not ventured into the period since the start of the war in the east. It has been marked by many thousands dead and injured in the fighting- more civilians than soldiers, a humanitarian crisis in the occupied territories [45], an exodus of a million, now internally and externally displaced people, a deepening economic and social crisis throughout the country, the imposition of western sanctions against Russia, rising nationalisms in Russia and Ukraine, military exercises and mobilisations by Russia and NATO across Eastern Europe. They amount to further escalation and widening of the conflict.

In this article I have tried to show it is not enough to examine the actions of the big powers in order to understand how this crisis began. Its tap root grows out of the historical experience of Ukrainian society and their state. It is the first and necessary condition for the activation of all the other roots. So too will the solution to the crisis grow out of Ukraine. It will have to confront the failure of the contemporary ruling class to fulfil the popular expectations arising from the attainment of independence in 1991 for prosperity, social justice, democracy and national self determination. And while the first three of these expectations were denied by the Ukrainian ruling class, the present war with Russia shows this same class is incapable of defending its country’s national independence. The current situation powerfully echoes the two previous attempts in history – in 1648 and 1917 – when a new social class tried but failed to build an independent state centred on Kyiv and the Dnipro River basin. Will the same happen again? Will Ukraine be reduced again to territory contested by the Great Powers?

Russia, the USA and the West European states all bear responsibility for their parts in this crisis. I have tried to show here that the political economy of Ukraine is stretched across a reknitted transnational capitalist economy in which Russia on the one hand and the Western powers on the other are vying to draw Ukraine’s ruling class, national market and productive assets into their respective integration projects. Despite trying for a quarter century, the Ukrainian state has been unable to gain membership in the political and military-security institutions of the Western, Euroatlantic project. Over the same period it has been refusing to join equivalent institutions of the Russia-led project.

My findings draw attention to the revival of Russian imperialism since 2000, the divisions in the Western alliance over policy towards Russia, and the diminished capacity of the USA to project its own power into the region. These three factors steadily altered the balance of power in Eastern Europe between these competing regional integration projects. The collapse of the Yanukovych regime gave Russia’s leaders the opportunity to exploit the changing balance, return to the initiative and try to draw Ukraine back into its own sphere. Russia militarised and internationalised the crisis. It provoked the Western powers to respond with economic sanctions and strengthening NATO’s capacity of its member states bordering Russia and Ukraine. Both the Western powers and Russia have pressed the Ukrainian leadership to engage with the separatist movement and seek a negotiated solution with them. The harder it is pressed the less becomes the room for its manoeuvre between them.

Whether it is Russia or the Western powers who claim Ukraine as part of their own sphere this can only be an imperialist claim. One or another faction of the Ukrainian ruling class may submit to such a claim, or even to a joint Russia-West tutelage over the country. Sooner or later their common class interests will lead them to it. But it will not be accepted by the Ukrainian people, nor should it be by those who want to support them around the world.

Notes

1. У 1994 р. то була загроза загального страйку, яка змусила Верховну Раду та Президента Леоніда Кравчука нарешті оголосити перші демократичні вибори до обох органів незалежної держави; у 2001 – наметове містечко на майдані Незалежності – «Майдані» – у Києві, що проголошувало гасло «Україна без Кучми» та вимагало відставки другого Президента, аж поки його було жорстоко придушено; та Помаранчева Революція у 2004 р., яка скасувала результати сфальсифікованих президентських виборів та привела до влади Віктора Ющенка.

2. Уряд зберіг у державній власності земельні ресурси, озброєння, авіаційну та аерокосмічну промисловість, трубопроводи зв’язку та енергоносіїв.

3. Стратегія Путіна також передбачала субординацію олігархів за політичною ознакою, винищення повстанської Чеченської держави ціною десятків тисяч життів, суттєву централізацію розслабленої федеральної системи, успадкованої від Бориса Єльцина, а також проведення неоліберальних реформ системи соціального забезпечення.

4. Alexey V. Kuznetsov, “Industrial and geographical diversification of Russian foreign direct investments”. Electronic Publications of Pan-European Institute, 7/2010; [link]; [link] .

5. Marko Bojcun, “Trade, investment and debt: Ukraine’s integration into world markets” in Neil Robinson (ed) Reforging the Weakest Link: Global Political Economy and Post-Soviet Change in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus; Ashgate, Aldershot, 2004; pp. 46-60.

6. Marko Bojcun,“The International Economic Crisis and the 2010 Presidential Elections in Ukraine”, Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics, Vol.27, Nos.3–4, September–December 2011, pp.496–519.

7. Кого "здав" на суді Фірташ: одкровення, які можуть викликати політичний землетрус в Україні - [link]

8. Фірташ купив свої активи за гроші Путіна - [link]; Петров: Якщо ви давно не бачили щасливу людину, то подивіться на мене - [link]

10. Тищук Т. А, Іванов О.В., «Шляхи протидії прихованому відпливу капіталу з України». (Ways to combat concealed capital flight from Ukraine), National Institute of Strategic Studies, 2012. http://www.niss.gov.ua/, accessed 14 November 2011.

11. Сергій Рахманін, «Усе вже вкрадено до нас…» [link]

12. НБУ [link]

13. Економічна правда [link]

14. Насправді зовнішньоторгівельний дефіцит України в торгівлі товарами зростав із 2005 року, особливо після вступу до ВТО. Див. статтю Олександра Кравчука Можливі соціально-економічні наслідки євроінтеграції для України(рис.6,7) – Прим. ред.

15. Водночас значною мірою зростання «іноземних інвестицій» в Україну було наслідком повернення грошей олігархів із офшорів. Див. статті «Пісок крізь пальці: офшори в українській і світовій економіці» Олексія Вєдрова та «Україна офшорна. Історія формування вітчизняної моделі економіки» Олександра Кравчука у «Спільному». – Прим. ред.

16. Bojcun, “The International economic Crisis”

17. Bojcun, “The International economic Crisis”.

18. Tyzhden’. 18 February 2013

19. Kuznetsov, “Industrial and geographical diversification”

20. Oleksandr Kravchuk, Історія Формування Боргової Залежності України (A History of the Formation of Ukraine’s Indebtedness); [link].

21. [link]; [link]; [link]; [link]; Financial Times 23 September, 26 November, 28 November 2013; 18 March, 8 April 2015.

22. [link].

23. World Bank (2011) Migration and Remittances Factbook 2011, [link]

25. [link]

26. Пояснення видається нам сумнівним. Куди ймовірніше, що уряд Януковича опирався входженню в Митний союз із Росією радше через перетин інтересів українських та російських олігархів на багатьох ринках, аніж через загрозу українській незалежності. – Прим. ред.

27. Також стосовно цієї зустрічі див. “Putin threatened to encourage the secession of the Black Sea peninsula of Crimea and eastern Ukraine” [link]. Див також звернення Путіна до Російських Федеральних зборів 4.12.2014.

28. Arkady Moshes, “Will Ukraine Join (and Save) the Eurasian Customs Union? ” - [link].

29. The Guardian 29 November 2013.

30. Kyiv Post 29.11.2013.

31. Насправді восени 2013 року МВФ пропонував відкриття кредитної лінії на 15 млрд дол. за умови скорочення соціальних витрат, зокрема – зменшення субсидій на газ для населення, замороження росту мінімальних заробітних плат, обсягів Пенсійного Фонду, а також загальну дерегуляцію економіки країни. – Прим. ред.

32. [link]; accessed 30.03.2015. Достеменність документу, опублікованого в «Новой газете» не було ані спростовано, ані підтверджено, тож наразі немає достатніх підстав повністю покладатися на цю публікацію як на свідчення планів російського керівництва. – Прим. ред.

33. Статус Ігоря Гіркіна як агента ФСБ на момент подій, змальованих у статті, можна розглядати лише як припущення автора. На момент анексії Криму Гіркін офіційно звільнився з ФСБ й обіймав посаду керівника служби безпеки інвестиційного фонду «Маршал-Капітал». – Прим. ред.

34. YouTube: [link].

35. Див. англійський переклад тексту кремлівського документу щодо цих планів; у оригіналі опубліковано у «Новая газета» 24 лютого 2015:[link].

36. [link]; accessed 14.05.2014.

37. Твердження автора щодо поширеності аргументів про загрозу етнічних чисток не є очевидним, оскільки в риториці сепаратистів на той момент переважали інші аргументи. – Прим. ред.

39. Див Zbigniew Marcin Kowalewski, “Russian White Guards in the Donbas”; тут англійською: [link]; Французькою тут - [link]. [link].

39. [link].

40. Financial Times, 24 June 2015

41. [link]. У відсотках від ВВП затрати Росії на оборону зросли від 3,9% у 2010 р. до 4,2% у 2013 р. За той самий період затрати США впали з 4,6% до 3,8%.

42. «Якби референдум щодо вступу України в НАТО проходив у липні 2015 року, проголосували б “за” 64% громадян і 28,5% – “проти”, вагалися з відповіддю – 7,5%, свідчать данні соцопитування фонду “Демократичні ініціативи” і Центру Разумкова». Дзеркало тижня, 3 серпня 2015 - [link]

45. Reiner Lindner, голова German-Ukrainian Parliamentary Group, Karl-Georg Wellmann, член Bundestag; Bernard-Henry Lévy, французький публіцист та активіст, Lord Risby, британський член парламенту, Karl-Georg Wellmann, член Bundestag, Gunther Verheugen, європейський комісар з питань ЄС у 1999-2004; Peer Steinbrück, архітектор програми захисту євро під час економічного кризи 2008 року, Laurence Parisot, віце-президент French Employers Association, Lord Mandelson колишній комісар ЄС з питань торгівлі, Rupert Scholtz, Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz, прем’єр-міністр Польщі у 1996-1997, Lord McDonald, Генеральний прокурор Англії та Уельсу у 2003 – 2008, та Bernard Kouchner – екс-міністр закордонних справ Франції і засновник міжнародної організації Medecins sans Frontiers.