Serbia in 2024: A mirror on capitalism’s global crises

There are countries that shape global politics and those shaped by it. Serbia belongs to the latter. As a small nation on the receiving end of global forces, Serbia often provides a sharper lens through which to observe capitalism’s global crises. The old saying goes, “When America has a cold, the rest of the world sneezes,” but smaller countries such as Serbia are often the first to display symptoms. In 2024, Serbia offered a particularly clear reflection of the three core dimensions — political, economic and systemic — of capitalism’s crises. These crises are not incidental; they are manifestations of contradictions inherent to capitalism. This text adopts a Marxist framework to examine these dimensions, highlighting how Serbia exemplifies broader global trends.

The political dimension: Decline of liberal democracy

The global crisis of liberal democracy has reached Serbia with full force. Boris Kagarlitsky’s (2024) critique of the “hollowing out” of democracy was evident in Serbia’s December 2023-January 2024 parliamentary elections. The Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) secured victory by receiving 48% of the votes — twice as much as the opposition — despite various political and corruption scandals plaguing its more than a decade in power. While the SNS often vilifies the previous government (now in opposition) to deflect criticism, this strategy has had diminishing returns over time.

Its victory can largely be attributed to the opposition’s inability to present a credible alternative to the electorate. This was exemplified by their campaign name, “Serbia Against Violence”, which emphasised what they opposed but failed to articulate what they stood for. The SNS, in contrast, employed various methods of regime legitimation. Along with criticism of the previous government, it frequently pointed to indicators such as GDP growth and increased foreign direct investment (FDI) as markers of its success.

Popular mobilisations, such as student protests over the Novi Sad Railway Station disaster, public outcry against the lithium extraction project in Jadar and, more recently, the destruction of the Old Bridge over the Sava in Belgrade, reveal another facet of the political crisis. These protests, while significant, lacked coherence and vision, resembling what Volodymyr Ishchenko (2024) describes as “Maidan revolutions” — uprisings that fail to consolidate into organised political movements.

These protests reflect another global trend: the weakening of the left as it further merges into liberal democratic discourse. Kagarlitsky offers a piercing analysis of this predicament, arguing that the left, in its retreat from working-class politics, has increasingly aligned with the urban bourgeoisie, adopting politically correct positions that prioritise symbolic issues over material struggles. This alignment has vacated political space for the right, which has opportunistically coopted elements of the working-class agenda, leading to a general rightward shift in the electorate. In Serbia, like many post-socialist countries such as Ukraine and Georgia, the absence of a genuine left-wing movement has exacerbated this political vacuum —unless one genuinely believes that Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS), long in cahoots with the ruling SNS, is a left party.

A December Faktor Plus poll is a clear indication of all this, as it demonstrates despite the wave of mass protests in Belgrade and other large cities in November and December, the balance of political forces has not changed. While the ruling coalition (SNS/SPS) still enjoys overwhelming public support at 54.8%, the popularity of the main opposition party, the Party of Freedom and Truth (SSP), is just 7.3%. Most people see the opposition as part of the same ruling elite and adopt the position that the devil they know is better than the devil they don’t. This situation bodes ill for the future of protest movements, as the absence of a cohesive and independent left often leads to cosmetic political changes that fail to improve the conditions of the working class. Instead, such movements frequently end up cementing the power of foreign and comprador bourgeoisies, leaving capitalism’s structural inequalities untouched.

A Demostat public opinion poll conducted in May revealed a striking contradiction between public satisfaction with personal living conditions and dissatisfaction with governance and democracy. While 81% of respondents said they were content with their living conditions and 60% approved of their working conditions, only 29% expressed satisfaction with the state of democracy, and just 38% approved of the government’s performance. Key areas of dissatisfaction included the fight against corruption and crime (67%), justice and courts (53%), and political freedoms and human rights (42%). Interestingly, mistrust was highest not toward the government but trade unions (61%), NGOs (69%) and opposition parties (69%). These findings encapsulate the paradox of citizens being “happy with their lives and unhappy with their government,” highlighting the disconnect between personal well-being and the state of governance and democracy in Serbia.

Serbia’s recent trajectory confirms its alignment with the framework of political capitalism (Branko Milanović, 2021) or “party state” model (Vesna Pešić, 2007), with events in 2024 have underscored the defining characteristics of this system. The political and economic fallout from the lithium mining project, anger over the Novi Sad Railway Station tragedy and dissatisfaction with the handling of election disputes collectively highlight how state and party structures intertwine to consolidate power while managing dissent. These events illustrate the inherent contradictions of political capitalism: steady economic growth (heavily reliant on resource exploitation and foreign investment) is sustained alongside democratic backsliding and systemic corruption.

As Milanović and Pešić explain, endemic corruption is a central feature of such a system. Discretionary decision-making, inherent to the system, allows elites to blur the boundaries between state and party functions, channeling resources and opportunities toward politically-connected actors. In Serbia, the merger between government and ruling party structures amplifies these dynamics, making corruption a recurring accusation during popular protests.

Public mobilisations in 2024 frequently centred on allegations of corrupt practices, highlighting the perceived exploitation of state power for private and partisan gain. This deepening corruption not only erodes trust in governance but stifles avenues for meaningful opposition, as the intertwining of party and state limits the scope for institutional accountability. The protests underscore the systemic nature of corruption in political capitalism, as well as its role in fuelling public dissatisfaction and amplifying demands for transparency and reform.

The erosion of trust and failure of collective action in Serbia reflect the decline of liberal democracy as a stabilising force within capitalism. As corruption becomes endemic in systems of political capitalism and populism or political extremes capture voter preferences, the legitimacy of democratic institutions has been weakened. This trend is evident not only in Serbia but in countries such as France, where the collapse of the centrist Barnier??? government mirrors the polarisation of Serbia’s political landscape. The global crisis of liberal democracy, characterised by rising discontent, institutional decay and the inability to address systemic inequalities, is no longer a distant spectre but an immediate and pressing reality.

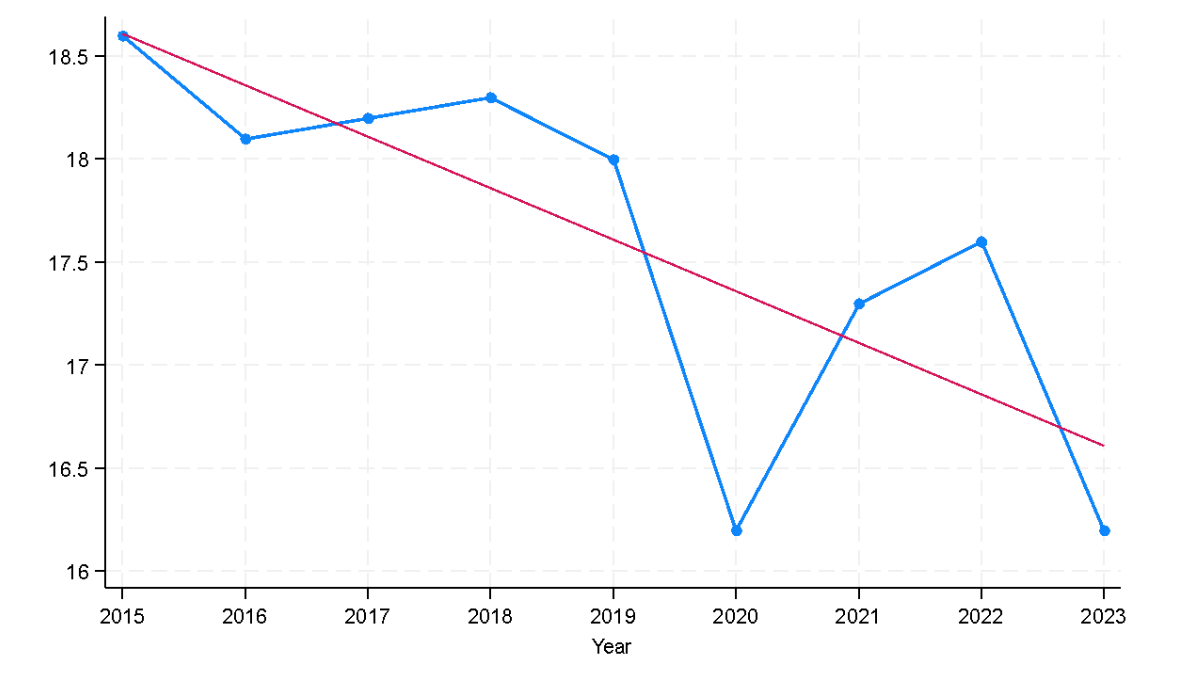

The economic dimension: Countering the tendency of the rate of profit to fall

Karl Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall underscores a central contradiction of capitalism: the pressure to maintain profitability amid declining returns on investment. The average rate of profit on US non-financial sector capital has been in general decline over the past decade, only partially recovering in 2021 and 2022 after the COVID-19 pandemic before declining again in 2023 (Figure 1). Contemporary capitalism counters this tendency through three principal strategies: increasing surplus value, generating waste and expanding to the periphery. These dynamics are particularly evident in Serbia, where global economic crises intersect with local manifestations of dependency and exploitation.

Increasing surplus value: Green Transition and labour exploitation

Globally promoted as a solution to environmental and economic challenges, the “Green Transition” often masks intensified surplus value extraction. In Serbia, the controversial Jadar lithium project, spearheaded by multinational corporations, exemplifies this trend. Marketed as an environmentally friendly initiative, the project primarily serves the interests of global capital by exploiting Serbia’s natural resources and cheap labour. It reflects what Samir Amin (1974) identified as the use of technological advancement to amplify surplus value extraction at the expense of workers and ecosystems. The Global Green Transition, as argued by developing countries, also “kicks away the ladder” (Ha-Joon Chang, 2002), placing an excessive burden on them while stymieing their development. Simultaneously, it creates significant investment opportunities for Western capitalists, often shouldered by state subsidies. This dynamic is particularly evident in the context of the Jadar project, as multinational corporations such as Rio Tinto stand to benefit far more than the host country.

The Serbian government has hailed the Jadar project as a transformative investment that could see GDP rise by 2-16%, depending on the scope of value-adding activities. However, GDP is a highly imperfect measure — not only because it excludes many economically and socially valuable non-market activities but because it reveals nothing about how the product is distributed or reinvested. The government implies that GDP rises will translate to improved living standards, yet this assumption remains highly questionable. If the lion’s share of profits is expatriated by Rio Tinto, Serbia becomes little more than a geographic location where profit is generated, without significantly impacting its development trajectory.

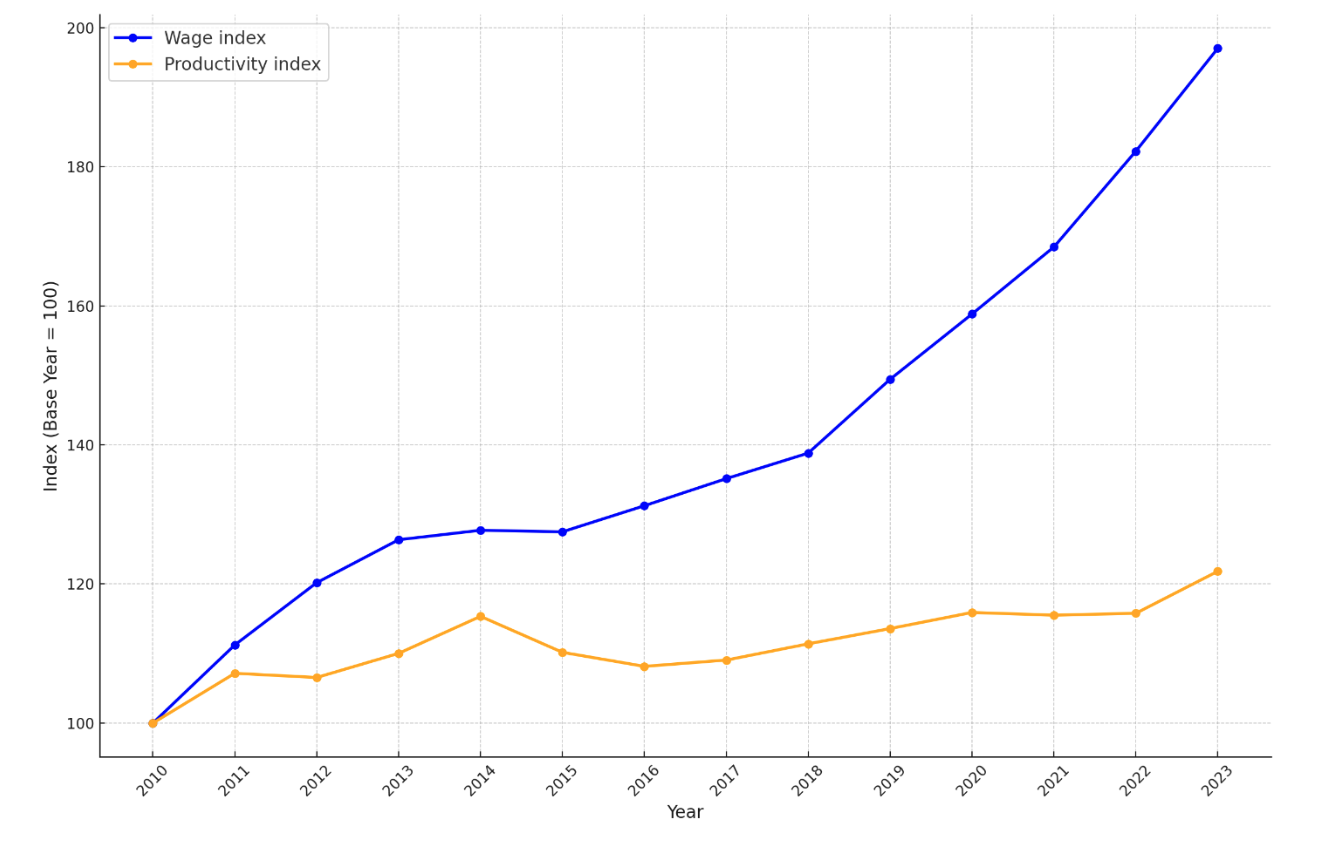

Internally, this exploitation is reflected in the persistent gap between labour productivity and wage growth in Serbia (Figure 2). Over the period from 2010 to 2023, average net wage growth consistently outpaced labour productivity (measured as output per hour worked). This trend became particularly pronounced after 2015, highlighting the decoupling of wages from productivity gains.

From a Marxist perspective, this divergence can be interpreted as a form of redistribution within the working class, rather than a fundamental shift in the dynamics of capital accumulation and surplus value extraction. While rising wages may temporarily improve worker’s living standards, they do not fundamentally challenge the structural logic of capitalism. Surplus value created by workers is still appropriated by capital, and observed wage rises could reflect the need to maintain social stability or to incentivise labour in a context of low productivity growth.

Looking ahead, as Serbia reintegrates into global supply chains and resumes its role as a peripheral economy within the capitalist world-system, the sustainability of these wage gains remains uncertain. FDI and export-oriented industries will likely prioritise cost competitiveness, potentially reversing the trend of wage growth outpacing productivity. This dynamic highlights the precarious nature of wage gains in addressing systemic inequality without broader structural changes to the mode of production.

This trend diverges from broader global dynamics, particularly in advanced economies such as the United States and in the European Union, where productivity has outpaced wages over recent decades. In the US, for instance, productivity rose by more than 60% between 1980-2020, yet real wages grew by only 17%. Significant disparities also exist between the productivity and wage trajectories of EU member states, exacerbating inequality. In contrast, Serbia’s experience of wage growth outpacing productivity reflects the specific conditions of its peripheral economy, where labour costs and social considerations play a distinct role. Nonetheless, this divergence still underscores the systemic inequalities inherent in contemporary capitalism, albeit manifested differently across the global economic hierarchy. This underscores the unique dynamics of Serbia’s integration into global supply chains, where competitive pressures on productivity are less intense compared to core economies.

This “pass-through” arrangement — where wealth flows through Serbia only to return to its origin with little left behind — reflects the structural inequalities of global capitalism. It highlights how GDP growth, in isolation, is a poor proxy for meaningful development, particularly in peripheral economies. Moreover, local resistance to such projects underscore growing discontent with exploitative arrangements, as communities question the ecological and social costs of hosting extractive industries for negligible national benefit.

Generating government waste

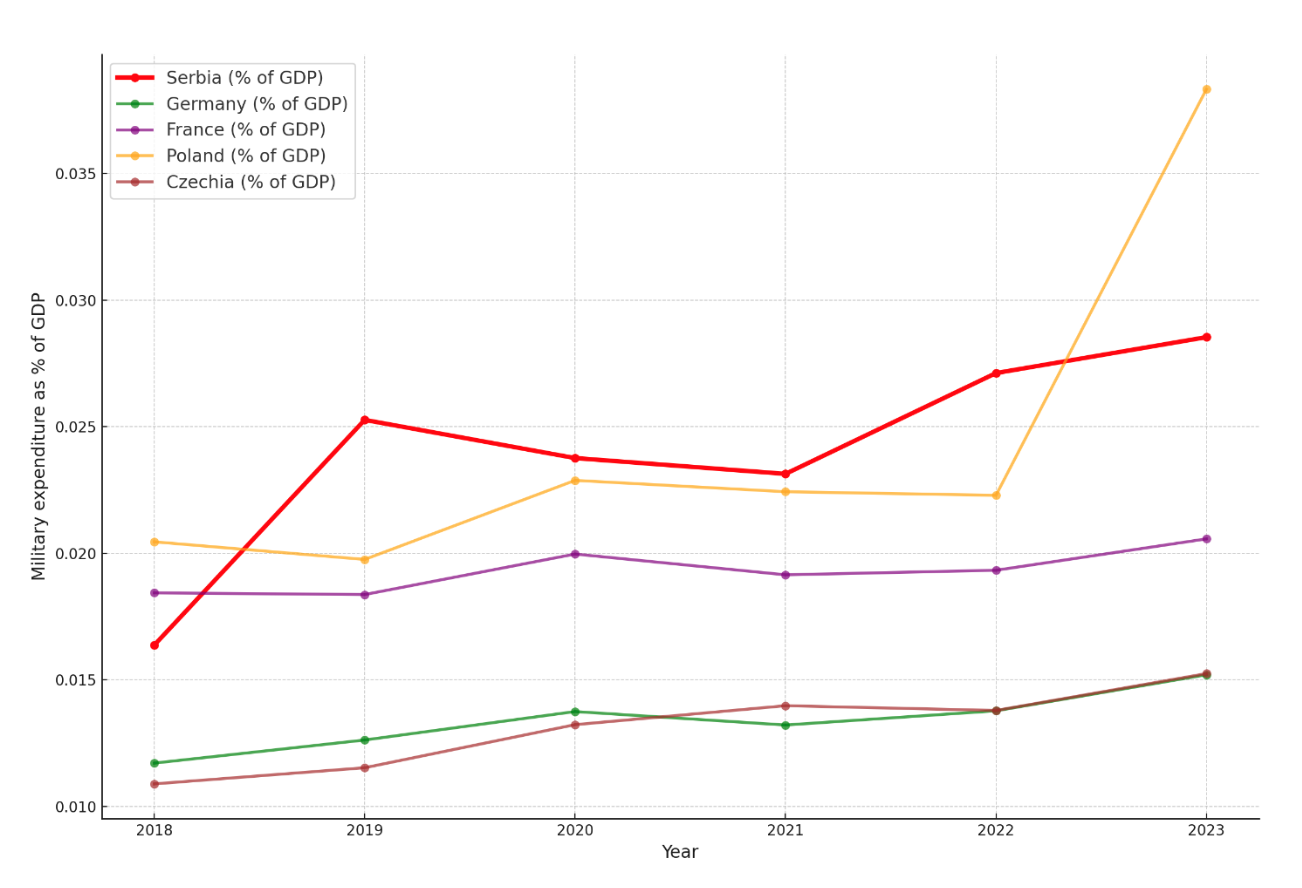

Another mechanism to counter the tendency of the rate of profit to fall is generating waste through unproductive expenditures. Serbia’s growing militarisation mirrors global trends of using military expenditures as a tool to absorb surplus capital. The country’s decision to reintroduce conscription and purchase 12 French Rafale fighter jets, at a cost of €2.7 billion, reflects an increasing reliance on militarisation, not as a strategic necessity but an economic imperative.

Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy’s (1966) analysis of monopoly capitalism elucidates how military spending functions as a pseudo-solution to systemic contradictions, creating demand without addressing structural issues. Michal Kalecki (1972) explained the appeal of military Keynesianism to capitalists, noting that it is “limitless” — unconstrained by the physical infrastructure needs of society — and does not compete with private sector provision, instead funnelling resources to private suppliers for “wasteful” purposes.

In Serbia, this form of waste aligns with significant increases in military expenditure, which rose from 2.2% of GDP in 2018 to approximately 3.6% of GDP in 2023. This represents one of the fastest rises in military spending in the region. Had Serbia maintained its 2018 level of military expenditure, approximately $1.02 billion — equivalent to 1.4% of GDP — could have been redirected toward socially useful purposes, such as education, healthcare or infrastructure development.

Figure 3 highlights Serbia’s sharp rise in military expenditures, which outpaced nearly all European countries, including NATO members. Despite not being a NATO member — and therefore not bound by the 2% GDP defence spending guideline — Serbia’s defence budget has grown at an extraordinary rate, standing second to only to Poland in Europe (whose exceptional rise is driven by its unique geopolitical situation).

From a Marxist perspective, Serbia’s escalating military expenditure represents a transfer of resources toward unproductive activities that sustain capitalism’s inherent contradictions while deepening its peripheral status. Military spending absorbs surplus capital, fulfilling a role in maintaining economic activity, without addressing underlying structural issues such as low productivity and economic dependency. This trend reflects the dual pressures of domestic political stability and regional integration into global arms markets, underscoring the opportunity costs of prioritising militarisation over structural transformation.

This form of waste is compounded by bloated government expenditures in the public sector, particularly in state enterprises. While the non-public sector has narrowed the wage gap from 22% to 5.4% since August 2020, the public sector still leads in terms of salaries. Notably, state enterprises have even higher average salaries. This wage structure, while providing stability for public sector employees, raises concerns about inefficiencies and misallocation of resources. Higher salaries in the public sector may not always align with productivity and can divert funds from critical investments in infrastructure, health, and education (Amin, 1974).

Together, these patterns of militarisation and inefficient public sector spending reflect systemic waste, reinforcing structural inequalities rather than addressing them. This misallocation of resources highlights the limitations of such expenditures as a means to counter capitalism’s inherent contradictions.

Expansion to the periphery: FDI

Serbia’s reliance on FDI exemplifies capitalism’s expansionary logic, where peripheral economies are integrated into global value chains primarily as sites for low-value-added production. Chinese investments in key sectors such as mining (the Bor copper mine), steel production (the Smederevo steel plant) and energy underscore how foreign capital dominates Serbia’s economy, extracting resources and profits while leaving structural weaknesses in the domestic economy unaddressed. This reliance locks Serbia into its peripheral status within the global capitalist system, with short-term GDP growth masking deeper dependencies.

In 2024, government officials hailed as a milestone that S&P had granted Serbia an investment-grade credit rating (BBB-) with a stable outlook. President Aleksandar Vučić and finance minister Siniša Mali highlighted the anticipated benefits of this upgrade: increased FDI inflows, lower borrowing costs on capital markets, and improved economic growth, employment and living standards. However, this optimistic outlook underscores Serbia’s ongoing dependency on foreign capital markets and external financing to sustain its economic model. While the investment-grade rating is likely to facilitate further borrowing and attract investors, it fails to address the structural constraints of an economy reliant on low-wage labour and resource extraction.

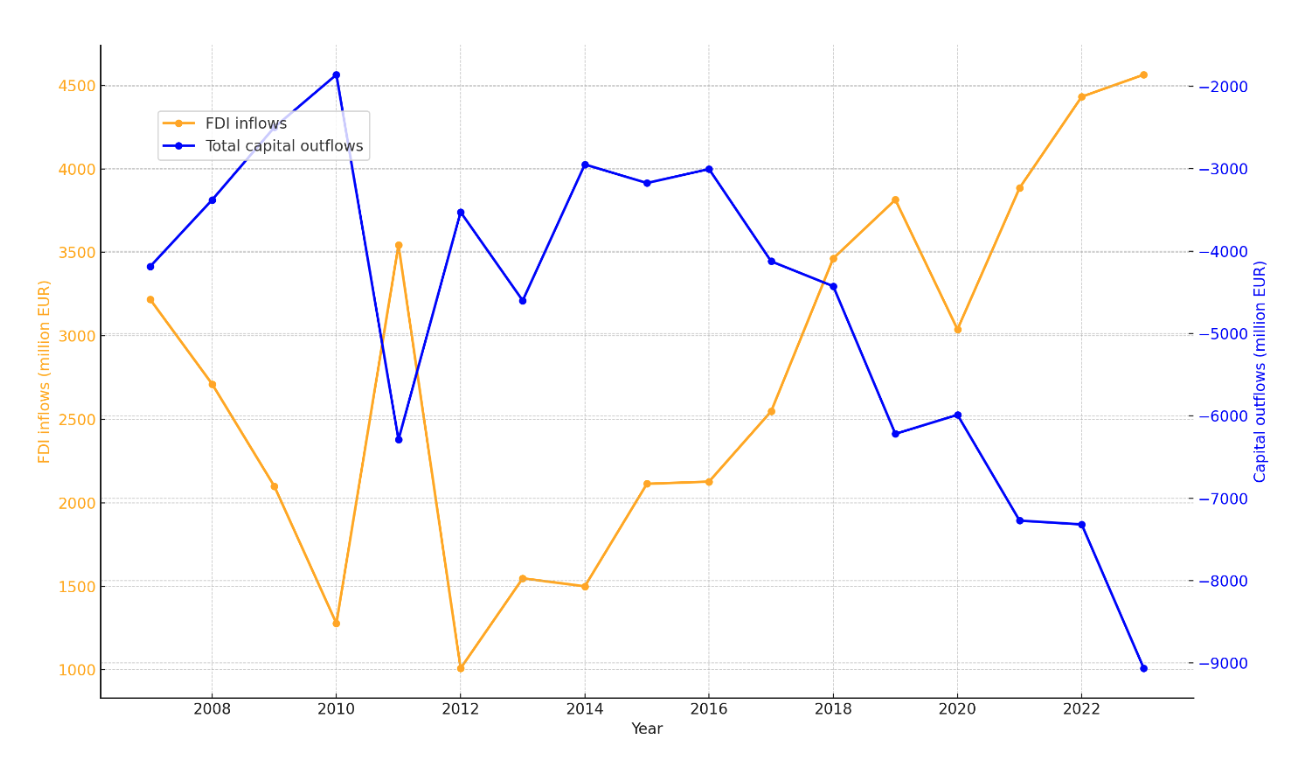

Amin (1974) argued 50 years ago that a rise in FDI in developing countries strengthens their dependence on goods and services produced in the capitalist centre and results in an increase in capital outflows. Indeed, the contrast between rising FDI inflows and growing total capital outflows highlights the contradictions of Serbia’s integration into global capitalism (Figure 4). Between 2007-23, FDI inflows steadily increased, peaking at €4.56 billion in 2023. In the same time, total capital outflows (including profit repatriation, reinvested earnings and interest payments) more than quadrupled, reaching nearly €9 billion. While FDI provides immediate capital inflows, it is accompanied by systemic value extraction, as profits generated in Serbia are repatriated to foreign investors, reinforcing the country’s role as a surplus exporter within the global system.

This dynamic is further reflected in Serbia’s debt servicing burden. Despite a significant decline in the foreign debt-to-GDP ratio, from a peak of 73.1% in 2012 to 59.4% in the first quarter of 2024, the debt service-to-GDP ratio has remained stubbornly high, about 10% over the past decade and reaching 11.4% in 2024. In 2025, the country is expected to pay €1.88 billion in interest alone, an increase of €300 million compared to 2024.

Despite government claims of improved borrowing terms following its investment-grade credit rating, the reality suggests otherwise. For example, loans denominated in dinars for EXPO 27 projects attract interest rates exceeding 8% (3-month Belibor + 3.3%), highlighting the rising cost of financing. This indicates that while the overall stock of debt relative to GDP has declined, the terms of borrowing or repayment structure have placed significant strain on the economy. From a Marxist perspective, these trends reflect a continuous transfer of surplus value to global financial markets, where peripheral economies such as Serbia incur high costs to sustain their integration into the global capitalist system.

Serbia’s leadership promotes FDI as a path to economic modernisation, but the reality is that such investments often prioritise profit repatriation over local development. Resource-intensive industries and environmentally damaging projects exacerbate social and ecological challenges while leaving little room for long-term, sustainable growth. Ultimately, Serbia’s strategy of attracting FDI and cheap capital serves to entrench its position in the global division of labour, ensuring that the benefits of growth remain unequally distributed domestically and internationally. Rising outflows of surplus value starkly demonstrate that while FDI might promise modernisation, it ultimately perpetuates Serbia’s dependency and peripheral status in the global economy.

The systemic dimension: Global fragmentation and declining Western hegemony

The decline of Western hegemony and rise of multipolarity are reshaping global politics, with Serbia positioned at the intersection of competing forces. This transition reflects broader systemic changes in the global capitalist order, as declining centres of power contend with the ascent of new players. Giovanni Arrighi’s The Long Twentieth Century (1994) provides a theoretical lens to understand this shift, highlighting how periods of hegemonic decline often coincide with the fragmentation of established power structures and emergence of new centres of accumulation.

Serbia’s balancing act reflects its pragmatic approach to navigating these shifting dynamics by maintaining ties with both Eastern and Western powers. This pragmatism is particularly evident in its response to EU pressure to impose sanctions on Russia, with Serbia continuing to rely heavily on Russian natural gas. More than 90% of Serbia’s gas imports come from Russia and Gazprom remains its dominant supplier. This reliance underscores Serbia’s economic vulnerability while highlighting its cautious steps toward diversification.

In 2024, Serbia began operationalising a gas supply agreement with Azerbaijan as part of its diversification strategy. Gas exports from Azerbaijan represent less than 15% of Serbia’s domestic demand of roughly 2.5 billion cubic metres a year, almost all of which is imported. But the initiative is considered significant for diversifying energy sources. The move also aligns with the EU’s broader strategy to reduce dependence on Russian energy, even as Serbia seeks to maintain favourable gas contracts with Russia.

The EU’s Growth Plan for the Western Balkans allocates €1.58 billion to Serbia over 2024-27, making it the largest recipient in the region. This funding, consisting of €525 million in grants and €1.05 billion in favourable loans, aims to support infrastructure development, the Green Transition and digitalisation. While the plan underscores the EU’s strategic interest in Serbia as a key regional partner, it also highlights the conditional nature of EU support, tied as it is to the Reform Agenda.

For Serbia, this initiative represents both an opportunity to advance its development goals and a challenge to navigate growing tensions between aligning with EU standards and maintaining ties with Eastern powers such as China and Russia. This balancing act, central to Serbia’s foreign and domestic policies, continues to shape its geopolitical and economic strategies.

In 2004, Serbia sought to diversify its partnerships beyond the West. Visits by Chinese President Xi Jinping and French President Emmanuel Macron to Belgrade exemplified the country’s strategic balancing act. Xi’s visit in May resulted in 28 agreements spanning infrastructure, energy, technology and trade, underscoring China’s strategic interest in Serbia as a regional gateway for its Belt and Road Initiative. Macron’s visit in August, on the other hand, highlighted the EU’s ongoing attempts to maintain its influence in Serbia and ensure alignment with EU policies. These visits represent contrasting global forces vying for influence in Serbia. But they are far from the full picture.

A political analyst reviewing the geography of high-level visits to Serbia in 2024 could equally defend opposing theses: that Serbia is an anti-EU Russian stooge aligned with the East, or an ardent pro-Western EU aspirant. On the one hand, the “Eastern” narrative is supported by the visits of Russian Minister of Economic Development Maxim Reshetnikov (coinciding with European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s visit in October), Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán (often seen as a thorn in the EU’s side), Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev. These high-profile engagements reflect Serbia’s strengthening ties with non-Western powers, emphasising its efforts to align with rising multipolar trends.

On the other hand, the “Western” narrative draws upon a similarly impressive roster of visits: in addition to Macron and von der Leyen, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz (June) and Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk (July) visited Serbia in 2024. These visits underscore the EU’s strategic interest in anchoring Serbia within its sphere of influence and advancing the country’s EU accession process. Serbia also hosted Ukrainian First Lady Olena Zelenska and foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba in May, signalling solidarity with Ukraine and its Western allies.

Yet, 2024 showed no surge of enthusiasm for EU accession within Serbia itself. A February 2024 NSPM poll revealed that support for joining the EU had fallen to 42.8%, with 36.8% opposed — a sharp decline from 75% support in 2006. Another poll indicated that 76% opposed EU membership if it required recognising Kosovo’s independence. These results highlight the increasing political divide and challenges surrounding Serbia’s EU integration process.

The EU’s ability to drive reforms through conditionality — a key factor in moving candidate countries to align with EU standards — has significantly weakened. No new negotiation chapters have been opened since 2021. Even the opening of Chapter 3 (on services), a relatively technical issue, has faced objections from eight EU member states due to Serbia’s non-compliance with EU foreign policy criteria. This stagnation reflects the broader disillusionment with the EU accession process, both within Serbia and among EU members, further complicating Serbia’s geopolitical positioning.

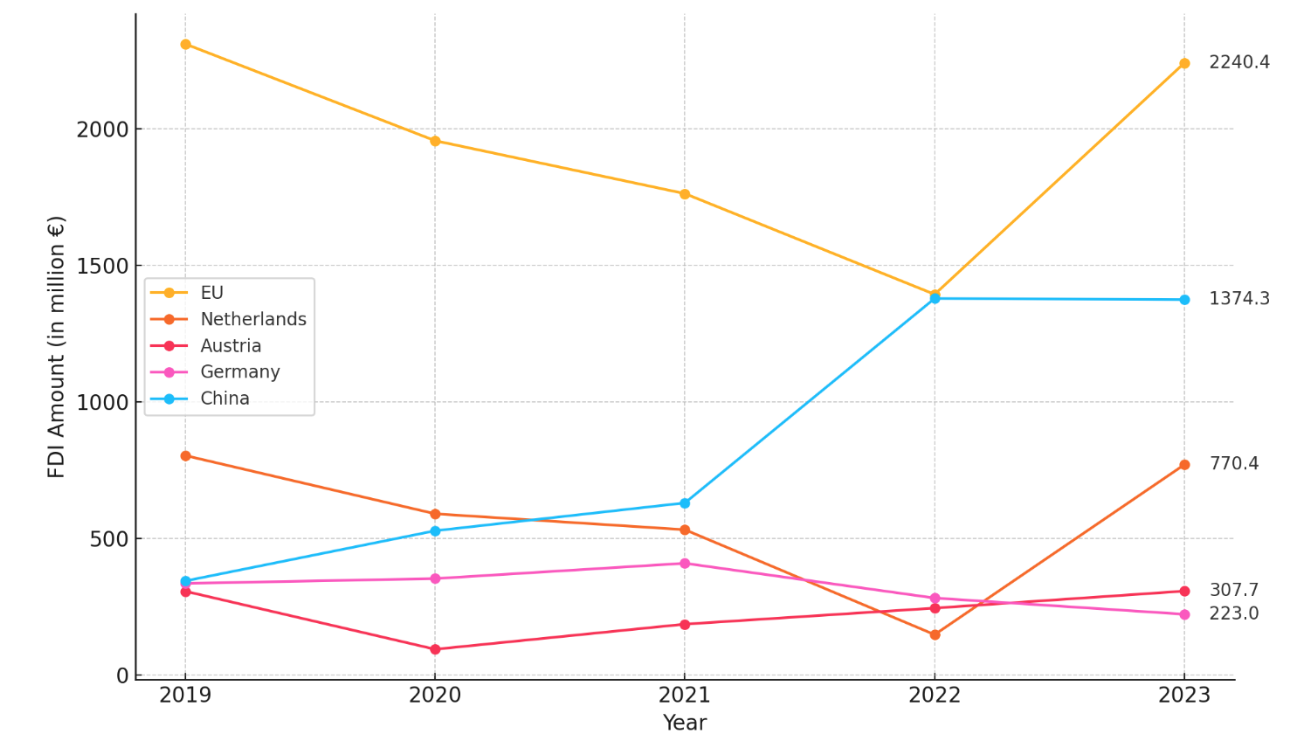

Serbia’s diversification strategy is also evident in its FDI patterns (Figure 5). While the EU collectively remains Serbia’s largest investor, in the past four years China has emerged as the single largest investor, with FDI inflows reaching €1.37 billion in 2023. This growth is particularly pronounced in sectors such as mining, energy and infrastructure, reflecting China’s strategic interest in Serbia as a gateway to the Balkans. Meanwhile, traditional EU investors, such as Austria and Germany, maintain their presence but are increasingly overshadowed by the growing influence of non-Western powers. Turkey plays a growing role in FDI, aligning with its expanding trade relations with Serbia.

As discussed above, the influx of FDI — whether from the EU or China — comes with challenges. While providing immediate capital and supporting GDP growth, it also facilitates significant capital outflows. This dynamic underscores the structural constraints of Serbia’s economic model, where the benefits of FDI are offset by profit repatriation and other forms of surplus value extraction. From this perspective, even China’s growing role as Serbia’s largest investor does little to mitigate the country’s peripheral status in the global economy, as foreign investments prioritise profit over local development.

Serbia’s multi-vector approach exemplifies its ability to manoeuvre within a fragmented global order. While trade ties with China and Turkey have expanded significantly, the diversification of FDI sources highlights the complexity of Serbia’s integration into the global economy. However, this diversification also exposes contradictions inherent in Serbia’s geopolitical positioning. Closer ties with China, Turkey and others bring new opportunities for investment and trade, but they also risk deepening dependency on external powers, albeit different from the West.

From a Marxist perspective, Serbia’s balancing act reflects the declining stability of the global capitalist system, where the core-periphery hierarchy is increasingly contested. The fragmentation of Western hegemony may open space for smaller states to assert agency, but it also highlights the enduring mechanisms of dependency, extraction and surplus value transfer that underpin global capitalism. Serbia’s experience demonstrates the potential and limits of navigating these tectonic shifts in global power, as the country remains firmly embedded in the contradictions of a fragmented world.

Serbia: A microcosm of the global crisis of capitalism

Events in Serbia throughout 2024 offer a microcosm of capitalism’s global crises. Politically, the deepening erosion of liberal democracy mirrors global trends of polarisation and stagnation. Continued SNS dominance, despite widespread dissatisfaction, highlights the inability of opposition forces to present a coherent alternative, a phenomenon Kagarlitsky aptly attributes to the left’s retreat from material struggles. The rise of populism, the absence of a genuine left, and the hollowing out of democracy reflect the systemic contradictions of capitalism, which is unable to provide stability even in its core, let alone in its periphery.

Economically, Serbia illustrates how capitalism counters the tendency of the rate of profit to fall through surplus value extraction, waste generation and peripheral expansion. The persistent gap between productivity and wage growth highlights the intensification of labour exploitation. Military spending and inefficient public sector wages, while absorbing surplus capital, fail to address structural issues and deepen Serbia’s dependency on external financing. FDI expansion, particularly from China, underlines the contradictions of globalisation. While providing short-term capital inflows, FDI is accompanied by systemic capital outflows and profit repatriation, reinforcing Serbia’s role as a peripheral economy within the global system.

Geopolitically, Serbia’s balancing act between East and West encapsulates the fragmentation of global hegemony. Competing visits by leaders from China, Russia and Turkey, on the one hand, and EU and NATO-aligned countries, on the other, underscore Serbia’s strategic importance in a multipolar world. Yet this diversification, while politically significant, fails to alter the underlying economic dependencies that tie Serbia to the core-periphery dynamics of global capitalism.

Taken together, these dimensions reflect the broader global crisis of capitalism — a system marked by declining hegemony, deepening inequalities and systemic contradictions. Rosa Luxemburg (1913) argued: “Capitalism, by its very nature, drives beyond national boundaries. The contradiction between its expansionary tendencies and the constraints of national and global systems leads inevitably to crises and, ultimately, its own demise.” Serbia’s experiences in 2024 not only mirror these global trends but offers a stark reminder of the enduring struggles of peripheral economies to navigate the crises of a deeply fractured world order.