Norway election: Labour narrowly holds on to power amid uncertainty

First published at Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung.

Norway’s parliamentary election on Monday, September 8, 2025, was an incredibly close-run race. The left bloc, led by the Labour Party, secured a narrow victory. Labour will likely continue as a single-party minority government, seeking compromises and budget agreements with other left-wing parties as well as across the political spectrum. Much remains uncertain, however, as negotiations with as many as four smaller left-wing parties are still ongoing before a new government can be formally established.

The race for the threshold

Norway’s multi-party system means that election outcomes often hinge on which parties surpass the 4 percent threshold for proportional representation. This year’s vote was no exception – in fact, it was even dubbed “the threshold election.” In the previous election, the radical-left Red Party (R) became the first newly established party in Norwegian history to pass the threshold, ensuring proportional representation in Parliament. This time, polls consistently showed the Red Party comfortably above the line, establishing itself as a permanent political force.

The real suspense centred on three other parties: the Green Party (MDG) on the left, and the Liberal Party (V) and the Christian Democratic Party (KrF) on the right. Their ability — or failure — to pass the threshold was widely seen as decisive for which bloc would secure power, and it fueled intense debate about tactical voting. The Greens in particular built their campaign almost entirely on the message that crossing the threshold was essential to keeping the far right out of government, symbolised by a campaign where prominent green politicians posed on pictures next to a massive wooden “4%” sign.

Tactical voting and a fragmented parliament

On the right, tactical voting is hardly new. Both the Liberals and Christian Democrats frequently hover around the threshold, and conservative voters are well aware that they are essential for forming a right-wing government. It is even said that some local Conservative Party (H) branches traditionally lend votes to the Liberals to ensure their survival. This year, however, the Conservatives performed unusually poorly. Having polled strongly in recent years, their support collapsed in the run-up to the election, dropping from 20.3 percent in the last election to 14.6. With fewer votes to spare, they could not bolster their allies as effectively. One key reason for their decline was the growing strength of the far-right Progress Party (FrP), which captured large numbers of Conservative voters and secured 23.9 percent of the vote.

In the end, the Green Party and the Christian Democratic Party cleared the 4 percent threshold, while the Liberals failed to do so. This secured victory for a left bloc of five parties that cleared the threshold, while the right bloc could only get three parties over the line. The Liberals will still have a parliamentary group consisting of three MPs, however — down by five — on account of winning a number of direct mandates in the counties.

Norway’s new “super PACs”

Another factor in the Conservatives’ poor performance was a heated national debate on wealth taxation. The Conservatives’ want to reduce Norway’s net wealth tax, while FrP wants to remove it completely. And of the two options, the more extreme stand seemed to be the most popular. Much of the campaign was dominated by a discussion of this tax, an issue pushed not only by right-wing parties but also by influential think tanks and lobby groups. Three self-described “super PACs” emerged, channeling large amounts of money into campaigns for the four right-wing parties while advocating for abolishing the wealth tax. These groups — “Action for Norwegian Ownership,” “Joint Action for Value Creation and Private Ownership,” and “Action for a Bourgeois Election Victory” — argued that the tax harmed Norwegian business owners, encouraged foreign takeovers, and in some cases forced entrepreneurs to sell shares to cover their tax bills.

Their narrative resonated strongly, even though only 14 percent of Norwegians pay the tax, and most of the burden falls on a small group of ultra-wealthy individuals. The “super PACs” dominated media coverage, circulating stories of struggling young entrepreneurs at risk of bankruptcy or emigration. Late in the campaign, the left finally mounted a stronger response. Asle Olsen, an oil engineer and Socialist Left Party (SV) member, launched a website called “Facts About the Net Wealth Tax,” which debunked many of the claims. He showed that the supposed hardship cases often involved companies with large surpluses and state support. Olsen accused mainstream media of neglecting their responsibility, and they seemed to listen, as they started to investigate the stories and arguments against the wealth tax themselves.

Unpopular attempts to “buy the election”

The left’s argument for keeping the tax is that, as Olsen exposed, it’s not true that it harms businesses in the way the right-wing claims. And secondly that this peculiar tax is the only way to tax the super-rich, as they are good at dodging others, like the income tax that most people pay. The Labour Party, initially cautious on this issue so as to maintain its business-friendly credentials, eventually joined the debate. Emboldened by shifting public opinion, they deployed their best guy, Finance Minister (and former NATO secretary general) Jens Stoltenberg, to defend the tax. This sharpened the contrast between the blocs and kept the issue alive in the media.

The outcome of this debate remains unclear, however. On one hand, the right succeeded in framing the tax as a threat to national ownership, embedding an Ayn Rand–style narrative of the embattled entrepreneur against an overbearing state. On the other hand, many voters grew weary of the topic, seeing it as irrelevant to everyday life. Moreover, Norway’s egalitarian ethos fits more with everyone paying their fair share and clashed with the optics of wealthy elites attempting to “buy” the election. The Christian Democrats, in particular, faced criticism for accepting large donations and then starting to claim that “Jesus would have cut the wealth tax.”

Social media and young voters

While taxation dominated much of the campaign, other issues also influenced the election, though often in less traditional ways. Media coverage frequently focused on “meta-debates” such as polling, the threshold question, and tactical voting, rather than on more substantive policy issues. Two other “meta-debates” that got significant attention were the related matters of the changing media landscape and engagement with young voters, especially young men.

A notable new trend during the campaign was the rise of social media in shaping political engagement, especially among young voters. Influencers on platforms like YouTube and TikTok interviewed top politicians, endorsed parties, or created explicitly political content. In addition to that, new influencers appeared that solely did political content to try to persuade voters, and also, of course, some politicians themselves began using these platforms innovatively, gaining significant followings.

Desperate media and a messy campaign

Traditional media followed these developments closely. For example, a group of young male YouTubers called Gutta (“the lads”) invited politicians from all parties to take part in a “20 vs. 1” interview format, in which each interviewee faced 20 disagreeing participants in a row. Although derivative of international YouTube formats and not particularly successful, the stunt drew substantial attention and commentary from mainstream media.

Mainstream media itself then began doing a lot of “stunts” and experiments to get attention in the new media reality. For instance, the public service broadcaster NRK made a series of nine interviews with the party leaders. The format — called Mørch og makta (“Mørch and power”, named after the host Erlend Mørch) — asked shocking and rude questions of the party leaders in addition to letting them present their program, and was quite successful and popular. Other large media outlets asked prominent politicians questions like how many people they had slept with and challenged them to games like “Fuck marry kill”.

All of this, in many ways desperate, silliness forced key issues in the background and made the overall campaign rather messy. Questions about youth political culture, voting behavior, and the growing appeal of right-wing movements among young men got a lot of traction. Meanwhile, issues of real concern to young people — things like climate change, housing, the rising cost of food, education, and job prospects — were often sidelined in the campaign.

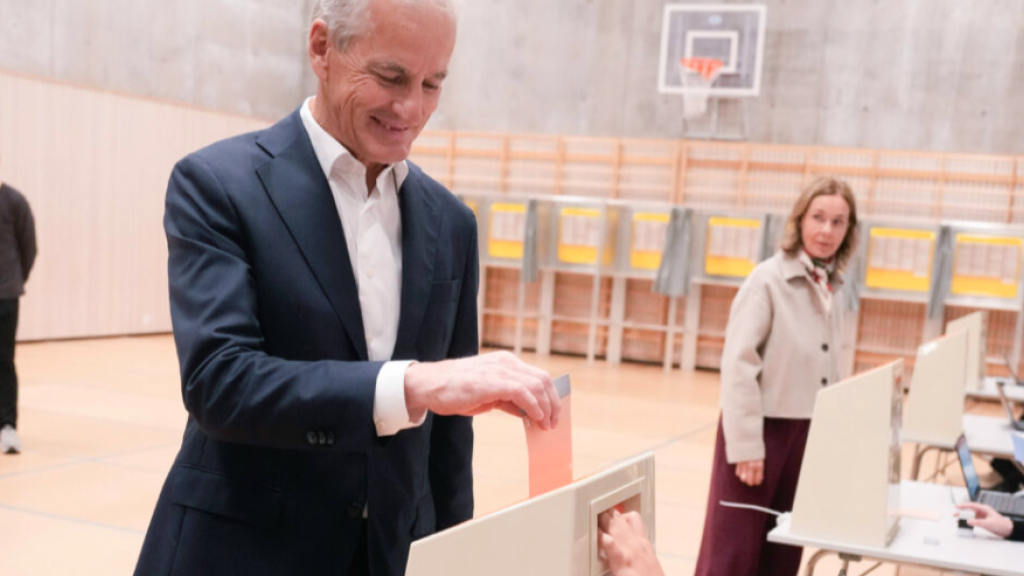

Uncertain times abroad

Foreign policy played a larger role in this election than is typical in Norway. With war in Europe and instability in the United States, the Labour Party benefited from its reputation for international competence. Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre, a respected diplomat who served as Foreign Minister from 2005 to 2012, enjoyed renewed popularity. Along with Foreign Minister Espen Barth Eide and Finance Minister Jens Stoltenberg, the government was widely seen as experienced and trustworthy.

Stoltenberg in particular plays a peculiar role in Norwegian politics. He was prime minister for a short time from 2000 to 2001, in which he made a series of reforms that made him popular with centre-right voters. Then he was prime minister again from 2005 to 2013, leading a red-green alliance. After that he was general secretary of NATO for ten years, which put him close to the inner circles of international politics and also US President Trump.

When he made a surprising comeback as Minister of finance in February this year, Stoltenberg was a key ingredient in the turnaround the government experienced in the polls, from being seen as chaotic and haunted by several personal scandals, to competent and the best bet to lead the country through uncharted waters. By contrast, the Conservatives were less trusted on foreign affairs, and the far-right Progress Party was viewed by many voters as simply unfit to represent Norway abroad. This perception may also have pushed some voters from the Liberals to the Greens.

Foreign policy controversies

Norway’s foreign policy has not been without controversy. The government’s recognition of Palestine, alongside Spain and Ireland in May 2025, was widely popular domestically and has energised the left. However, the government faced criticism over the investments of Norway’s sovereign wealth fund in companies linked to Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territories. After public scrutiny, the fund eventually divested from 11 Israeli firms and later from Caterpillar, provoking backlash from US Republicans, including Senator Lindsey Graham, who suggested imposing tariffs and visa restrictions in retaliation.

The Conservatives, Christian Democrats, and Progress Party accused the government of politicising the sovereign wealth fund, even though its decisions are formally made by Norges Bank, who follows clear guidelines that didn’t change during the campaign. Left-wing parties, meanwhile, called for deeper divestment, with the Red Party, Socialist Left, and Greens all campaigning on an openly pro-BDS platform. The Liberals also voiced support for Palestinian rights but had limited credibility due to their alliances with pro-Israel parties.

A new political reality

The previous election, four years ago, was shaped by a rural revolt against an unpopular right-wing coalition. The Center Party (Sp) thrived, forming a government with Labour. But that coalition became increasingly unpopular and plagued by scandals. In January 2025, the Center Party quit the government over disputes about the EU’s fourth energy market package. The Center Party hoped to re-establish itself as a more powerful force in opposition by leaving the government and tapping into sentiment opposed to ceding further sovereignty to Brussels. Labour, meanwhile, hoped that governing alone would give it greater room to maneuver.

This gamble paid off for Labour but not for the Center Party, which collapsed in this election. Prime Minister Støre staged a dramatic comeback, transforming himself from a “political dead man” into a strong leader whose popularity has now carried Labour to victory. The party now seems poised to once again govern alone, a role it has historically relished.

January’s debacle didn’t change much in the population’s view on the EU, but it did highlight the fact that the EU remains a constant issue in the Norwegian debate. Both political blocs also have parties for and against the EU, making it difficult to have a clear-cut debate about joining the union. (On the right, the Conservatives and Liberals are for the EU and the Christian Democrats and the Progress Party against, while on the left, Rødt, SV and the Center Party are against, Labour is split, and the Green Party is for). Whether or not Norway should integrate more with the EU without membership remains an ongoing debate, however, and it will be a painful one for the government in the coming years, as several of their coalition partners have conflicting views on this matter.

Changing landscape on the left

The big shock this election was that the far-right more than doubled their share of the vote, leaving Norway in a similar situation to many other European countries: ruled by a centre-left party, but with the strong far-right in second place and dominant on the right-wing of politics.

On the left, the radical left party Rødt (R) had its best election ever, winning 5.3 percent of the vote (up 0.6 percent). This success stems in large part from the party’s long-term strategy of establishing themselves as a working-class party, and a heavy focus on workers’ rights and expanding the welfare state. The Socialist Left party (SV), traditionally the bigger party on the left of Labour, performed worse this election, however, ending up just above Rødt with only 5.5 percent. The party appears to have been squeezed between a more confident Red Party and the Green Party’s campaign on tactical voting.

The main issues for the left — nature and climate, Palestine, welfare and inequality and poverty — were all taken up by Rødt, SV and the Greens, leaving them to fight for many of the same voters. This was the case despite the Green Party actually being a party of the centre, which likes to insist that it’s not part of the left bloc. Nonetheless, the party has a tendency of clarifying its position before each election, and this time it were firmly on the left, basing much of its campaign on a Green vote being a safeguard against the far-right gaining power.

In the end, then, the left bloc won the election, but still this vote has delivered a far less convincing mandate for change than the previous one. In 2021, the left secured 100 of 169 parliamentary seats, campaigning on class politics and economic reform. This year, the left holds only 88 seats compared to the right’s 81, leaving Labour reliant on difficult negotiations with its allies. With the potential instability this brings, the challenge now is not only to govern effectively but also to contain the far-right in the years ahead.

Ellen Engelstad (born 1985) is a Norwegian writer and editor at Manifest Publishing. She is the author of Syriza: The Athens Spring and the Struggle for Europe’s Soul (2016) and Rosa Luxemburg: A Biography (2019, co-written with Mímir Kristjánsson).