Paul Le Blanc: The essential and non-essential in Lenin

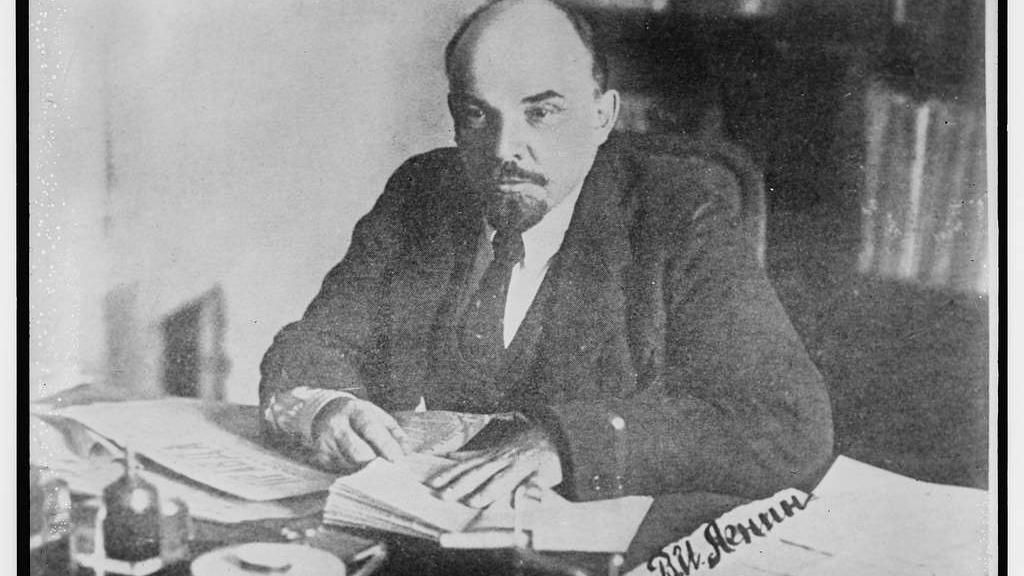

The hundredth anniversary year of Vladimir Lenin’s death has generated a remarkable outpouring of explorations and evaluations that are in dramatic contrast to the flat, two-dimensional dogmas that became dominant during the Cold War years of 1947-90. Those seeking an understanding of Lenin are now presented with much to consider that is complex, multifaceted, vibrantly alive and, perhaps, urgently relevant. Along with a proliferation of books, articles, forums and conferences, there has been a four-month online series of keynote addresses and panel discussions under the rubric of “Leninist Days/Jornadas Leninistas” — and all of this provides only a partial sense of the richness of this phenomenon. As the Leninist Days organizers emphasize, “100 years without Lenin” at the same time adds up to “100 years with him.” Much has changed, much has evolved, and much is different. Much is also the same — but in new ways.

We will focus here on one of the many issues to emerge in all of this. It relates to a challenge regarding a point raised in my new Lenin book and in my Leninist Days presentations — that some aspects of Lenin’s thought and practice are essential for serious revolutionaries, and other aspects are non-essential.

Historical framework of the essential and non-essential in Lenin

In the book Lenin: Responding to Catastrophe, Forging Revolution, I note that “one can certainly find, in what Lenin said and did under one or another circumstance, things that were rigid or dogmatic or authoritarian or wrong or overstated… But the essential thrust of Lenin’s thought and practice went in the opposite direction from such limitations.” I also add an opinion — “that humanistic and democratic ‘opposite direction’ has the greatest relevance for those who would change the world for the better.”1

Later in the book, I quote from Rosa Luxemburg: “What is in order is to distinguish the essential from the non-essential, the kernel from the accidental excrescencies in the politics of the Bolsheviks.”2For Lenin, genuine freedom and democracy are inherently anti-capitalist and revolutionary. A deep commitment to such freedom and democracy is essential to Lenin’s revolutionary goal, and also to his strategic orientation for achieving that goal.3

More than one person has challenged this approach to Lenin. Does defining “what is essential” to Lenin involve a desire to pick and choose only what appear to be the “nicer” aspects of Lenin’s orientation? Is this truly a materialist approach, or is it a recipe for a very subjective utopianism? These are valid questions, assuming we take them seriously — which means actually doing the research to determine what happened. These actualities matter. As Lenin stressed, “facts are stubborn things.”

Sufficient evidence has been amassed — by an impressive cluster of outstanding historians — to demonstrate that Lenin and his Bolshevik comrades were sincerely and effectively committed to a dynamic blend of democracy and socialism, and that they became a hegemonic force in Russia’s labor and revolutionary movements, helping to inspire a mass insurgency — a militant alliance of workers and peasants — that swept away the Tsarist order in 1917 and advanced in the direction of rule by democratic councils (soviets) and socialism. Out of all this, Lenin and his comrades created a global network of revolutionaries, the Communist International, to help generate revolutions in countries throughout the world. They saw this as essential for the future of socialism — and for the future development of the revolutionary process in Soviet Russia.4

As we know, the outcome was qualitatively different from the realization of a democratic and socialist order — in Soviet Russia and on our planet. The incredibly harsh years of 1918-24 (the year of Lenin’s death) culminated in the consolidation of a Communist Party dictatorship that modernized the new Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, consisting of most of the old Russian Empire. This modernization also involved an ongoing murderousness and repressiveness generally labeled Stalinism, named after Lenin’s successor. The three most influential explanations for this development go something like this:

It was all necessary and good — consistent with the democratic and humanistic aspirations of the 1917 revolution, and (whatever the difficulties and contradictions) are destined to triumph.

What happened demonstrates that Lenin’s aspirations, methods and goals were evil, and consistently so, from inception to realization — with loudly proclaimed democratic commitments simply a cover for totalitarian power-lust;

The genuine revolutionary-democratic commitments of Lenin and his comrades were overwhelmed by catastrophic developments.

The first two explanations predominated during the Cold War rivalry of the USSR and the capitalist West. The first cannot be taken seriously at least since the collapse of the USSR. Although the second consequently became the prevalent explanation, it was contradicted by much of the amassed evidence previously referred to. Only the third explanation is consistent both with that amassed evidence and with what we know of what happened between 1924-91. We will consider two items which support the explanation that the revolutionary-democratic commitments of Lenin and his comrades were overwhelmed by catastrophic developments. One is a primary document from 1920, a widely disseminated discussion of “the dictatorship of the proletariat” by a prominent Bolshevik leader, Lev Kamenev. The other is a careful study of the early functioning of the Soviet government by scholar Lara Douds.

While Karl Marx and such co-thinkers as Luxemburg and Lenin had defined the term “dictatorship of the proletariat” democratically as political rule by the working-class, by 1919 it had come to mean a dictatorship exercised by the Russian Communist Party, the name adopted by the Bolsheviks in 1918. This has often been seen as the essential, defining attribute of “Leninism.” Yet Lenin’s knowledgeable and sophisticated comrade Lev Kamenev scoffed at the notion that “the Russian Communists came into power with a prepared plan for a standing army, Extraordinary Commissions [the Cheka, secret police], and limitations of political liberty, to which the Russian proletariat was obliged to recur for self-defense after bitter experience.”5

Immediately after power was transferred to the soviets, he recalled, opponents of working-class rule were unable to maintain an effective resistance, and the revolution had “its period of ‘rosy illusions’.” Kamenev elaborated: “All the political parties — up to Miliukov’s [pro-capitalist Kadet] party — continued to exist openly. All the bourgeois newspapers continued to circulate. Capital punishment was abolished. The army was demobilized.” Even fierce opponents of the revolution arrested during the insurrection were generously set free (including pro-tsarist generals and reactionary officers who would soon put their expertise to use in the violent service of their own beliefs). Kamenev went on to describe increasingly severe civil war conditions that finally changed this situation, ending a period of “over six months (November 1917 to April–May 1918) [that] passed from the moment of the formation of the soviet power to the practical application by the proletariat of any harsh dictatorial measures.”6

This is corroborated by an anti-Leninist scholar from the Cold War period, Alfred G. Meyer, who commented that “the unceremonious dissolution of the Constituent Assembly” in January 1918 hardly constituted the inauguration of Bolshevik dictatorship: “for some months afterwards there was no violent terror. The nonsocialist press was not closed until the summer of the same year. The Cheka began its reign of terror only after the beginning of the Civil War and the attempted assassination of Lenin, and this terror is in marked contrast with the lenient treatment that White [counter-revolutionary] generals received immediately after the revolution.”7

Also significant is Lara Douds’ more recent scholarly study, Inside Lenin’s Government: Ideology, Power and Practice in the early Soviet State. The government referred to is commonly known as Sovnarkon, an acronym for Sovet Narodnykh Komissarov (Council of People's Commissars). As Douds notes, Lenin and his comrades believed that by carrying out a revolution to give all power to the soviets, “they were constructing a novel and superior democratic system.”8

“There were competing visions among radical socialists who led the new regime of how this Soviet democracy was to be expressed in practice,” Douds explains, “but government by Sovnarkom combining supreme executive and legislative power, responsible to the hierarchy of Soviets from local to national level, expressed at the center in the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets (Vserossiiskii Tsentral’nyi Ispolnite’nyi Kmitet or VTsIK), was initially the institutional form it took.” She documents that “the history of the first years of Lenin’s government illustrates that the monolithic, authoritarian party-state was not the immediate nor conscious outcome of Bolshevik ideology and intentional policy, but instead the result of ad hoc improvisation and incremental decisions shaped by both the complex, fluid ideological inheritance and the practical exigencies on the ground.”9

Douds engages with what she sees as “the overlooked but fascinating ways in which Soviet leaders attempted to apply elements of Marxist and socialist thought to the institutions at their disposal to create a superior form of democracy, although the experimental and innovative measures they trialed ultimately failed to deliver a freer and fairer system and instead crystallized into a dysfunctional state apparatus and a Communist Party dictatorship by the death of Lenin in 1924.” But the party dictatorship is not how it all started out. Initially it was the government of soviets, not the party, that was predominant. “In the first year or two after the October Revolution, Sovnarkom’s apparatus was certainly more developed than the equivalent party apparatus, which only began to expand from spring 1919.”10

Douds gives attention to the dynamics of the two-party coalition that first governed the newborn Soviet Republic — the Bolsheviks (soon renaming themselves Communists) and the Left-Socialist Revolutionaries, which broke down due to the precipitous actions of the Left SRs in reaction against the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. She also gives attention to the multi-party character of the soviets, in which Mensheviks, Socialist Revolutionaries, Left-Socialist Revolutionaries, and other oppositional leftists had voice and vote, until the relentless brutalization of the Russian civil war caused this to give way to repressions imposed by Lenin’s Communists.11

Douds also gives attention to the collegial, democratic-collectivist ethos that was initially predominant within the various components of the Soviet government, although the crises and catastrophes of civil war, foreign intervention, and economic collapse resulted in this giving way to more authoritarian modes of functioning. She traces Lenin’s efforts to push back against the ballooning of bureaucratic functioning and the erosion of Soviet authority through the increasing incursions of the Communist Party — efforts which proved to be doomed to failure.12

Causes for the failure are, Douds’ research suggests, only partly attributable to the aggressive assaults on the revolutionary regime by powerful and vicious enemies within Russia and globally. The replacement of multi-party democracy by single-party dictatorship quite naturally made the party predominant, and the relative autonomy of soviet institutions quickly melted away. While touching on this, however, Douds gives weight to deficiencies she sees in Lenin’s 1917 classic, The State and Revolution. Whatever its strengths as a work of historical-intellectual excavation in the views of Marx and Friedrich Engels, she finds it naïve and deficient as a blueprint for constructing a new form of government.13

Identifying the essential and non-essential in Lenin

This conceptual framework suggests an approach for determining the essential and non-essential in Lenin’s thinking. Karl Radek has recounted a comment made to him regarding some of his old writing: “It’s interesting to read now how stupid we were then!”14Surely one would be justified in consigning whatever those “stupidities” were to what was non-essential in the corpus of Lenin’s thought. In my explorations of Lenin’s thought and general approach, the following eight components seem essential:

- A belief in what Georg Lukács called “the actuality of revolution” — or as Max Eastman put it, a rejection of “people who talk revolution, and like to think about it, but do not ‘mean business’ … the people who talked revolution but did not intend to produce it.”15

- A commitment to utilizing Marxist theory not as dogma, but as a guide to action, understanding that general theoretical perspectives must be modified through application to “the concrete economic and political conditions of each particular period of the historical process.”16

- Building up an organization of class-conscious workers combined with radical intellectuals — operating as a revolutionary collective, both democratic and disciplined — capable of utilizing Marxist theory to mobilize insurgencies to replace the tyrannies of Tsarism and capitalism with democracy and socialism.17

- An approach to the interplay of reform struggles with the longer-range revolutionary struggle, permeated by several qualities: (a) a refusal to bow to the oppressive and exploitative powers-that-be; (b) a refusal to submit to the transitory “realism” of mainstream politics; and (c) a measuring of all activity by how it would help build the working-class consciousness, the mass workers’ movement, and the revolutionary organization that will be necessary to overturn capitalism and lead to a socialist future.

- An insistence that the revolutionary party must function as “a tribune of the people,”18combining working-class struggles with systematic struggles against all forms of oppression, regardless of which class was affected — deepening and extending into the centrality of a workers’ and peasants’ alliance in the anti-Tsarist struggle.

- A strategic orientation combining the struggle against capitalism with the struggle for revolutionary democracy (including a republic, a militia, election of government officials by the people, equal rights for women, self-determination of nations, etc.). Lenin stressed “basing ourselves on the democracy already achieved, and exposing its incompleteness under capitalism, we demand the overthrow of capitalism, the expropriation of the bourgeoisie, as a necessary basis both for the abolition of the poverty of the masses and for the complete and all-round institution of all democratic reforms.”19

- Characterizing global capitalism as having entered an imperialist stage, involving economic expansion beyond national boundaries for the purpose of securing markets, raw materials and investment opportunities, embracing all countries in our epoch — oppressed by competing and contending elites of the so-called “Great Powers.”20

- A consistent, unrelenting revolutionary internationalism: understanding that capitalism is a global system, seeing struggles against exploitation, oppression and tyranny that global solidarity and global organization are essential to socialist revolution.

One can argue that much of this is not unique to Lenin, but all of it is essential to the “Leninism” of Lenin.

Of the non-essential in Lenin’s political thought and practice, several examples suggest themselves. In this category we can place the unanticipated post-1917 emergency measures cited by Kamenev. Among the earlier examples, it can be argued that Lenin was, in his polemics with others on the left, prone to indulge in unfair exaggeration and uncomradely ridicule. That was certainly the judgment of some of his comrades who shared Lenin’s basic orientation and edited the Bolshevik newspaper Pravda and who, much to his chagrin, turned down 47 of his contributions between 1912-14, at one point admonishing that “his strong language and sharpness go too far.”21Despite his complaints, Lenin did not split from his comrades over this — a clear indication that we are dealing with something that was not essential.

Or consider this hostile critique by an anti-Leninist named Moissaye Olgin22from the Jewish Labor Bund, describing Lenin’s orientation as the revolutionary upsurge of 1905 was beginning to collapse:

In 1906, after the dissolution of the first Duma [tsarist parliament], when it became evident that absolutism had retained its power — when the mass of the peoples were becoming disappointed and revolutionary organizations were crumbling and the collapse of the revolution was evident — Lenin was preaching nothing less than an immediate armed insurrection. He urged the creation of an army of conspirators, to consist of groups of from five to ten “professional revolutionists,” those groups to go among the people and stage an insurrection.23

The Bundist critic saw this as a consistent feature of Lenin’s orientation, writing (in the months of 1917 between the overthrow of the Tsar and the Bolshevik seizure of power) that “now, as before, he advocated an armed insurrection.” Yet the critic fails to note that by 1907, Lenin was breaking away from the “armed insurrection” orientation (which continued to be advanced by his erstwhile co-thinker Alexander Bogdanov). At times he was even voting with the Mensheviks for non-insurrectionary electoral work, trade union efforts, and reform activity by the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party, to which both factions still belonged. This culminated in a sharp internal struggle among the Bolsheviks, in which Lenin led a majority in breaking from those around Bogdanov. All of which suggests — contrary to what is implied by the critic — that Lenin’s 1906 perspectives were not an essential element in his general revolutionary orientation.24

There is also a significant cluster of significant developments, taking place during the final years of Lenin’s life. In the catastrophic period of civil war and foreign intervention which followed the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, when optimistic expectations were overwhelmed by a desperate struggle simply to survive, there were a number of emergency measures and authoritarian improvisations — which had never been part of the Bolshevik orientation between 1903-17 — but that were advocated by Lenin and/or implemented by the new Communist regime. This resulted in protests and critiques from many Bolshevik comrades who had been close to Lenin up until this period, gathered in such groupings as the Workers’ Opposition and Democratic Centralists. Some of Lenin’s comrades also expressed concern over the repressive operations of the secret police, the Cheka. In addition to supporting the creation and many activities of the Cheka, Lenin condoned and even advocated the use of brutal and sometimes murderous human rights abuses, and also (perhaps “only” rhetorically) threatened, in 1921, to have socialist critics of his policies shot. The establishment of the Communist Party dictatorship was described by prominent Bolshevik Mikhail Tomsky in this way: “Under the dictatorship of the proletariat, two, three or four parties may exist, but only on the single condition that one of them is in power and the others in prison.” (Tomsky employed this joke in 1927 against long-time comrades of Lenin who, after Lenin’s death, opposed the policies of the bureaucratic regime represented at the time by Stalin and Nikolai Bukharin.) Such policies have been presented as representing the very essence of Leninism, rather than as the emergency measures and authoritarian improvisations that they actually were.25

In fact, many of these “non-essential” qualities in the Leninism of Lenin did become essentials of the “Leninism” associated with the ideology and regime associated with Stalin. For many in the larger world, such repressive and cynical qualities came to characterize much of the Communism prevalent in the Stalin era. The powerful propaganda apparatus of the Stalin regime affirmed that such “Communism” was firmly grounded in the ideas and actions of Lenin.26

The same message was conveyed by the powerful propaganda apparatus of the anti-Communists.

Lenin for revolutionaries

Many want something better than the crises and calamities of the status quo. Yet if we are passive, it seems likely that such a future, or something even worse, will finally triumph over us.

A society in which the free development of each person will be the condition for the free development of all people, in which we all share in the labor that would make this so, sharing in the fruits of our labor, with liberty and justice for all, a society of the free and the equal — it would be good to make that dream real. This would be an alternative worth striving for.

Efforts to bring this into being have more than once ended in failure and disappointment. Yet only through such efforts can any advances toward genuine democracy and freedom and a better life for all be made real. Nor is it realistic to see this as something that can simply be achieved once and for all. It is a never-ending story of continuing struggles that give meaning to life and hope for the future.

Increasing numbers of those who are aware of the situation we are in, and who engage in struggle to open a different and better pathway for humanity, are becoming revolutionaries. To be more effective, such people may commit themselves to making use of the positive insights and examples associated with what we have identified as essentials of Lenin’s orientation.

This essay served as the basis for a shorter presentation delivered online for Marxism 2024 in Istanbul on May 24.

- 1

Paul Le Blanc, Lenin: Responding to Catastrophe, Forging Revolution (London: Pluto Press, 2023), p. xv.

- 2

Ibid., p. 122.

- 3

Paul Le Blanc, “Lenin’s Socialism: Labels and Realities,” Links: International Journal of Socialist Renewal, 14 March 2024, https://links.org.au/lenins-socialism-labels-and-realities

- 4

A sampling includes: Alexander Rabinowitch, The Bolsheviks Come to Power: The Revolution of 1917 in Petrograd (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017); Ronald G. Suny, Red Flag Unfurled: History, Historians, and the Russian Revolution (London: Verso, 2017); David Mandel, The Petrograd Workers in the Russian Revolution: February 1917-June 1918 (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2018); Lars T. Lih, Lenin Rediscovered. “What Is To Be Done?” in Context (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2008); Tamas Krausz, Reconstructing Lenin, An Intellectual Biography (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2015).

- 5

Lev Kamenev, The Dictatorship of the Proletariat (Detroit: Marxian Educational Society, 1920); reproduced in Al Richardson, ed., In Defence of the Russian Revolution: A Selection of Bolshevik Writings, 1917-1923 (London: Porcupine Press, 1995, pp. 102-110); also on Marxist Internet Archive: https://www.marxists.org/archive/kamenev/1920/x01/x01.htm.

- 6

Ibid.

- 7

Alfred G. Meyer, Leninism (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1967), p. 193.

- 8

Lara Douds, Inside Lenin’s Government: Ideology, Power and Practice in the early Soviet State (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018), p. 2.

- 9

Ibid., p. 4.

- 10

Ibid., p. 10.

- 11

Ibid., pp. 97-124.

- 12

Ibid., pp. 149-68.

- 13

Ibid., pp. 11-20.

- 14

Radek/Lenin quoted in Le Blanc, Lenin: Responding to Catastrophe, Forging Revolution, p xv.

- 15

Eastman and Lukács quoted in Le Blanc, Lenin: Responding to Catastrophe, Forging Revolution, pp. xii, 10.

- 16

V.I. Lenin, “Letters on Tactics,” Collected Works, Vol. 24 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1974), p. 43.

- 17

Paul Le Blanc, Lenin and the Revolutionary Party (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2015).

- 18

V.I. Lenin, What Is To be Done? in Collected Works, Vol. 5 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1961), p. 423.

- 19

V.I. Lenin, in “The Revolutionary Proletariat and the Right of Nations in Self-Determination,” Collected Works, Vol. 21 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1974), p. 408.

- 20

See Paul Le Blanc, “Lenin, Imperialism, and Revolutionary Struggles,” Irish Marxist Review, Vol. 13, No. 37 (2024).

- 21

R. Carter Elwood, The Non-Geometric Lenin: Essays on the Development of the Bolshevik Party 1910-1914. (London: Anthem Press, 2011), p. 44.

- 22

By 1920, after immigrating to the United States, Olgin reevaluated his orientation, and became part of the Communist movement.

- 23

Moissaye J. Olgin, Lenin and the Bolsheviki (New York: Revolutionary Workers League, 1936; reprinted from Asia, Volume 17; Number 10, December 1917), p. 12.

- 24

Ibid., p. 12; Le Blanc, Lenin and the Revolutionary Party, pp. 129-152; Paul Le Blanc, “Learning from Bogdanov,” in Revolutionary Collective: Comrades, Critics, and Dynamics in the Struggle for Socialism (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2022), pp. 49-75.

- 25

Barbara Allen, Alexander Shlyapnikov, 1885-1937: Life of an Old Bolshevik (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2016); Charter Wynn, The Moderate Bolshevik: Mikhail Tomsky from the Factory to the Kremlin, 1880-1936 (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2023), p. 263.

- 26

See David Brandenberger and Mikhail V. Zelenov, eds. Stalin’s Master Narrative: A Critical Edition of the History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks), Short Course (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019).