From South Africa to Syria: The rising perils for Palestine solidarity

The sudden regime overthrow in Syria and the long-delayed opportunity to confront the legacy of Bashar al-Assad’s tyranny comes at a time that poses profound challenges for solidarity with Palestine.

These problems are particularly acute in South Africa given the government’s two-faced approach to Israel: condemnatory at The Hague, yet with President Cyril Ramaphosa apparently now backing away from anti-genocide “megaphone diplomacy” and allowing increased profiteering from exports to Israel (coal, diamonds, grapes and even bullets).

Pretoria enters the West Asian drama — this time stage right

A common concern in Johannesburg is that Trumpism’s return to power will hasten the genocide of Palestinians and erasure of their homelands, as well as further destabilise West Asia and amplify a long-lasting Washington-Pretoria-Tel Aviv relay in which mutual economic interests dominate.

Beyond the historic function of the three states collaborating in 1970s-80s nuclear weapons technology, the relay dates most conspicuously to Ramaphosa predecessor Jacob Zuma’s capitulation to Barack Obama and local South African Zionists during an earlier Gaza War.

A repeat performance is most worrying to progressives, in large part because South Africa’s Richards Bay bulk minerals port has become the world’s main terminal for exporting coal to Israel, which depends on the Orot Rabin and Rutenberg power stations for nearly 20% of its energy grid.

It is to be expected that incoming US President Donald Trump will go on the offensive against South Africa’s International Court of Justice (ICJ) genocide case against Israel. Trump is a proponent of Israel’s mass murder and illegal settlements, calling predecessor Joe Biden a “very bad Palestinian” during a debate in June for not sufficiently helping Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to “finish the job” in Gaza.

But instead of helping to build the global movement against Israel by highlighting Trump’s threats, Ramaphosa’s new Ambassador to Washington Ebrahim Rasool — formerly part of the ruling party’s left-wing currents — let slip in an interview this week: “We need to put away the [Palestine solidarity] megaphone now. And the president’s words were, it is now sub judice ... I understand the need to completely recalibrate … that’s the art of the deal. It is about framing the messages in particular ways that make South Africa an ally [of Trump].”

Some might be surprised at this betrayal, including Ramaphosa’s nonsensical sub judice posture. Yet beyond its important ideological advocacy megaphone at the Hague, the Pretoria government has barely lifted a finger for Palestine.

Backlash against Pretoria

The Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) strategy called for by a broad range of Palestinian civil society peacefully addresses one of Israel’s major vulnerabilities: fossil-energy supply. Yet Ramaphosa’s brother-in-law Patrice Motsepe runs a major mining house that partners with Glencore (as did Ramaphosa until he became deputy president in 2014), which serves as the main co-supplier of coal to fuel Israel’s genocide of Palestine.

Activists continue to insist on BDS, ending diplomatic recognition of Israel, and prosecuting South African mercenaries who illegally serve the Israel Defense Force (IDF), but they are making virtually no progress.

South African BDS Coalition coordinator Roshan Dadoo wrote in Amandla!: “South Africa is increasingly being seen as hypocritical, as it does not follow through with implementing the findings of the ICJ … Government has certainly not taken all measures within its power. The Department of International Relations and Cooperation says that coal sales to Israel are a trade-related matter. The BDS Coalition Energy Embargo campaign has been trying to meet the Department of Trade, Industry and Competition, but with little success. A meeting was set up and then cancelled at the last minute, leaving activists frustrated.”

Reflecting that frustration, leading personalities associated with South Africa’s three main (often fractious) local progressive political traditions — which could be termed “multipolar”, “independent-internationalist” and “liberal-constitutionalist” — penned a strong open letter. This included former intelligence minister Ronnie Kasrils, trade union leader Zwelinzima Vavi and anti-apartheid veteran Reverend Frank Chikane. They warned: “It looks increasingly like the South African government is reluctant to follow its own logic and uphold its legal obligations to isolate and sanction apartheid Israel.”

According to Kasrils, Vavi and Chikane, those obligations include following the ICJ Advisory Opinion ruling offered in July to halt “aid or assistance in maintaining the situation created by Israel’s illegal presence in the Occupied Palestinian Territory.” The vast majority of countries voting at the United Nations General Assembly in September (including South Africa) agreed with the ICJ that the world must “prevent trade or investment relations that assist in the maintenance of the illegal situation created by Israel.”

Coal fuels genocide

But as Kasrils, Vavi and Chikane observe, coal mined by Glencore and its longest-standing Johannesburg partner, African Rainbow Minerals (ARM), is still being “ supplied to Israelto generate electricity used to fuel genocide, the Israeli Occupation Forces, including production of military equipment, and maintaining the system of apartheid and illegal settlements.”

In spite of ICJ and UN mandates, trade minister Parks Tau claimed in parliament when asked about coal a few weeks ago: “Sanctions applied by one member against another in the absence of multilateral sanctions by the United Nations would violate the World Trade Organisation principle of non-discrimination and would open the country to legal challenge.” Tau’s specious argument results in his refusal to regulate a dangerous export, a commonly-used state tool.

Tau is not the only minister to ignore appeals to abide by the ICJ/UN mandate to disempower the Israeli genocidaires. Pretoria’s transport minister Barbara Creecy also refuses to answer BDS correspondence, though she is responsible for Transnet, whose “rail shipments and Richards Bay port facilitation subsidise the export of coal, which is a state-owned natural resource,” complain Kasrils, Vavi and Chikane.

Another culprit of dereliction is environment minister Dion George, who last month co-chaired the climate mitigation committee of the UN climate summit in Azerbaijan (the main supplier of oil to Israel). As Kasrils, Vavi and Chikane point out, over the past year, with a coal price “average of $110/ton, Glencore earns net profits of $40 for each ton of coal sold, with production costs of $70/ton. Each ton burned creates 2.6 tons of CO2 emissions. The resulting ‘social cost of carbon’ is $1056/ton burned, resulting in a net negative impact of nearly $2-billion climate damage due to South African coal sold [to Israel] since October 2023. So, these coal shipments fuel both Israel's genocide and the climate crisis.”

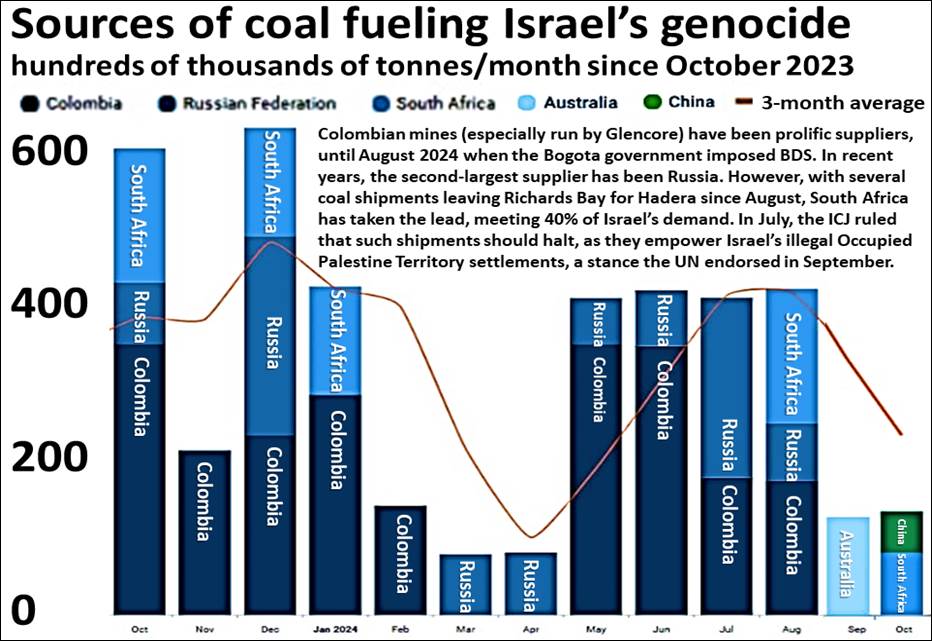

South Africa’s supply is increasingly vital to Israel, which currently relies on coal to power 17.5% of its national electricity grid. The last time fully-disaggregated UN Comtrade coal data was available, in 2021 (before Russia disguised its trade due to sanctions), Israel imported 6.5 million tons of which 50% was Colombian, 36% Russian, 13% South African and 1% Turkish.

In 2023, Israel consumed 5.2 million tons. According to a June 2024 SPGlobal report, between January-May, of 1.4 million tons Colombia accounted for 60% and “other key suppliers included Russia with 247,500, South Africa at 169,200, the U.S. at 86,100 and China supplying 53,000.”

In May 2024, Turkey imposed full trade sanctions on Israel, although dishonest shippers rerouted exports. The maritime-data company Kpler issued South African BDS activists with new data in November for ships bringing coal to Israel’s Hadera and Ashdod coal ports, revealing that a Chinese firm has apparently resumed shipments, along with one from Australia.

Another data source, Vessel Tracker, revealed last week that Colombia did not conclusively halt coal shipments, as anticipated in August, because on November 27 the Navios Felix took a load of coal — most likely from Glencore — to Hadera. The same ship was in Richards Bay on August 11 to load South African coal to Hadera, arriving on September 27, as its owner Navios Partners acknowledged how its fleet ships “for a broad range of high-quality counterparties, such as … Glencore.”

South Africa became Israel’s main coal supplier in August — overtaking Russia — with more shipments in September-November. Four shipments supplied Israel’s Hadera Port and Orot Rabin power station in recent weeks, each carrying 165,000 tons of South African coal. After the genocide began last October, at least seven ships have left Richards Bay carrying coal to Israel.

Glencore as BDS coal target

As the world’s largest commodity trader, Glencore offers no apologies or rationale. In May, at Glencore’s Annual General Meeting, one shareholder asked: “If [Glencore is] conducting human rights assessments on the use of the coal you’re exporting to Israel to ensure that you’re not held liable?” Board Chairman Kalidas Madhavpeddi replied: “The company supplies to many countries around the world and it’s almost impossible to tell you the answer to your question.”

The shareholder followed up: “So you don’t check how the coal is being used?” Madhavpeddi replied: “Coal is used in power generation, that’s simple.” The two Johannesburg-born South African Glencore directors at the AGM – CEO Gary Nagle and Senior Independent Director Gill Marcus – were notably silent during the questioning.

In 2006, ARM Coal was set up thanks to a $135 million loan to Motsepe from Glencore’s predecessor Xstrata, along with nearly half the firm’s investment capital. The deal was a major reason Motsepe vaulted to become South Africa’s richest Black businessman. That year, Xstrata bragged of 13 million tons of coal exports from Richards Bay: “Outside of Europe, Israel was the largest purchaser of the South African operations’ coal production.”

Glencore acquired Xstrata in 2013, inheriting the relationship with Motsepe’s ARM Coal. Meanwhile in 2014, Ramaphosa sold his own Glencore-allied firm, Shanduka Coal — including a stake in the enormous Glencore-owned Optimum Mine whose board Ramaphosa chaired — to become SA’s deputy president. As head of the Eskom “war room” in 2014-15, Ramaphosa allegedly instructed the power utility to pay a price 3.5 times the former cost of Optimum coal, with profits to Glencore.

Since its 1994 renaming from Marc Rich & Co, Glencore has had a terrible reputation in Africa. Initial earnings included apartheid-era sanctions busting for white South Africa. Its Congolese dealings with Israeli tycoon Dan Gertler continued until the latter’s 2018 blacklisting by the US government. From 2018-22, Glencore was successfully prosecuted under the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act for widespread bribery and corruption across Africa and Latin America, and paid $1.5 billion in fines. (Suspiciously, it has not been subject to prosecution in South Africa.)

Colombia’s Israel coal sales were typically 5% of recent exports, but in South Africa’s case the equivalent was usually lower than 1%, although that may rise to 2% in 2024. Earnings from these exports fluctuate with price and quantity: $101 million in 2021, $184 million in 2022 and $78 million in 2023. But the full costs of coal exports — in terms of local pollution, greenhouse gas damage and depleted hydrocarbons, as well as labour, operating costs and environmental remediation — are far higher than gross income.

Still, any worker or community adversely affected by BDS against Glencore and other coal mines prevented from selling to Israel, should in 2025 be first in line for compensation from $14 billion in SA’s Just Energy Transition funding.

Another demand made to Glencore at an August 22 Johannesburg protest was pay reparations, as Detroit-based General Motors did for profiteering in pre-1994 apartheid South Africa. All firms supporting Israeli genocide should now appreciate this risk.

More SA-Israel trade, perhaps including arms

Stopping coal sales to Israel is crucial but Pretoria also turns a blind eye to the lucrative diamonds and grape trade. Plus, there are new concerns that a 50% upsurge of artillery ammunition being produced by SA parastatal arms firm Denel, in a joint venture with German arms manufacturer Rheinmetall, is finding its way to Israel.

Moreover, both in Pretoria last month and in the US state of Delaware’s bankruptcy courts in August, another weapons link was unveiled when Johannesburg native Ivor Ichikowitz declared that several divisions of his Paramount Group (Africa’s largest privately-held arms dealership) were unable to pay creditors. One of Ichikowitz’s bankruptcy protection requests was for Paramount Industrial Holdings, whose Johannesburg factory was subject to an anti-genocide protest in November 2023.

Paramount South Africa — set up in 2018 to allegedly support “black economic empowerment” but mainly so as to gain access to SA military procurement contracts — is being accused by United Arab Emirates officials of merely asset-stripping Intellectual Property, which is technically owed to Abu Dhabi Autonomous Systems Investments following a London arbitration ruling against Ichikowitz.

In the process of trying to escape a huge debt to the Emiratis’ drone-manufacturing parastatal, Ichikowitz disclosed not only a previously-reported ongoing joint venture with Elbit, but that the main Israeli arms company retains an address at Ichikowitz’s Johannesburg factory.

Ichikowitz also revealed Paramount’s $725,000 debt to the Israel office of Cognyte Technologies, a spyware firm known previously as a component of Verint, which was prosecuted for corruption in the US and criticised by Amnesty International for contributing to South Sudanese surveillance abuses. Cognyte is also under investigation by Israeli courts for providing technology to the Myanmar junta as it carried out a coup and civilian killings in early 2021.

Earlier this year, South Africa’s leading investigative journalists’ non-profit, Amabhungane, objected to the secretive nature of another of Ichikowitz’s divisions that went bankrupt: “By operating in low scrutiny jurisdictions, the Paramount group might have placed itself outside of the oversight structures in South Africa that restrict military trade. In addition, questions have been raised about the alleged funding of political interests ranging from South Africa’s ruling party to politicians abroad, and whether political connections have enabled the expansion of the company outside South Africa.”

For much of 2023, the Ichikowitz Family Foundation was indeed the single largest funder of Ramaphosa’s ruling party, the African National Congress. Later in the year, as the genocide got underway in Gaza, the same foundation was a brazen, public supplier of tefillin (spiritual leather garb) to the IDF. As South Africa’s anti-genocide ICJ case began, Ichikowitz published articles in the Chicago Tribune and Fortune condemning the proceedings.

Delaware court documents suggest the need for a relook by the Pretoria regulator supposedly monitoring such deals, the South African National Conventional Arms Control Committee (NCACC). Several months ago, the notoriously lax NCACC lost a human rights case in local courts for approving an illegal Myanmar arms deal. The same committee had offered late-2023 denials that Ichikowitz and other local firms worked with the IDF, in spite of Ichikowitz’s mysterious Tel Aviv office and his tefillin supply to the genocidaires.

BDS must intensify

Could BDS help end the genocide and other IDF attacks? Kasrils, Vavi and Chikane conclude: “As South Africans, we know that sanctions in support of our liberation struggle played a vital role in bringing down the apartheid regime.”

Indeed, in 1985, financial sanctions caused such a squeeze that President PW Botha declared a debt default, imposed exchange controls and shut the stock market. The response by business leaders was to visit Zambia to meet exiled Black leaders, beginning the democratisation process, as whites fearful of further meltdown finally accepted “one person, one vote” democracy.

But one reason activists suspect sanctions will not be imposed unless pressure rises is the role of Motsepe, a generous financial contributor to a range of local political parties. With a net worth estimate of nearly $3 billion, he is Johannesburg’s richest resident.

Motsepe is also the president of the Confederation of African Football and therefore, along with other Federation Internationale de Football Association executives, continues to delay suspension of Israel players from international fixtures, a demand made due to their extensive collusion in genocide and apartheid.

Will activists overcome Pretoria’s failures to impose sanctions, cut diplomatic relations (as was mandated by parliament in November 2023), and prosecute young mercenaries who take their gap year after Herzlia and King David High School degrees to serve as paid IDF genocidaires?

A growing activist coalition will be needed. Dadoo notes that “South Africa’s largest trade union federation, the Congress of South African Unions, and its affiliate, the National Union of Mineworkers, support a ban on coal exports to Israel. So do environmental groups and social justice movements in the country.” Long gone are the days Ramaphosa organised a national strike as the National Union of Mineworkers leader, 37 years ago.

But links between the various movements are growing, for example at a protest on August 22 at Glencore’s Johannesburg headquarters and Cape Town oil company branch, and again on October 8, when climate activists included a protest at the Ichikowitz Family Foundation office during an anti-fossils march — in part because of his role providing military ship and air support to protect Big Oil operating offshore Nigeria and Mozambique. A leader of SA Jews for Palestine also addressed the crowd.

Syrian chaos

Another factor that makes BDS work more important everywhere, is Syria’s new government. After pounding his citizenry with bombs and bullets since the Arab Spring arrived in Syria in March 2011 — leaving more than 600,000 dead and six million exiled refugees — Assad witnessed the carving of his country into a balkanised set of territories characterised by US, Russian, Turkish and Israeli land and resource grabs.

The stunning 12-day military campaign coordinated by Hayʼat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and its leader Abu Mohammed al-Jolani began the day after Lebanon’s remaining Hezbollah leadership signed a dubious ceasefire with Netanyahu’s regime on November 27. On December 6, the IDF demolished the Lebanon-Syria crossing to prevent Hezbollah from importing arms from Iran, but also to halt any Lebanese fighters’ defense of Assad against the rapid HTS advance into the capital Damascus.

This has provoked a series of reactions, including at least three dueling left-wing narratives, as usual distinguishing between an emphasis on top-down geopolitics and bottom-up social-struggle:

- The first focuses on a critique of the role of imperialist and sub-imperialist powers — especially Washington, Tel Aviv and Ankara — in a behind-the-curtain “dirty war” manipulation of HTS jihadis. An example of this is Mohammad Marandi’s account of Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Biden’s current de facto support for al-Qaeda extremists, or Vijay Prashad’s summation that “Israeli bombardment of Syrian military facilities had weakened the Syrian armed forces’ logistical and ordinance capabilities… [and] attacks on Iranian supply depots and military facilities in Syria as well as the attacks by Israel on Iran had prevented any build up of Iranian forces to defend the Syrian government… conflict in Ukraine had certainly denied Syria the ability to call upon further Russian assistance… HTS has received aid and support from Turkey, but also covertly from Israel.”

- The second, in contrast to manipulation, is based on a recognition that for US and Israeli military interests, as Gilbert Achar puts it: “The Assad regime and HTS are almost equally bad.” The focus is instead on sectarian religious infighting (which weakened the government army’s commitment to defend Assad) plus degraded Iranian, Hezbollah and Russian support for Damascus, which together provided a gap for HTS’ advance. This narrative holds profound concerns that the extreme Islamist values of HTS and its allies, and oppression of secular democratic forces, means very tough times ahead, including for the Rojava movement of progressive Kurds in north-eastern Syria; and

- The third narrative, which focuses on a celebration of the role of popular will in overthrowing the brutal Assad regime, leaves us with a generally-progressive, bottom-up success story containing democratic and anti-patriarchal potentials, notwithstanding some dubious elements and threats of restored sectarian extremism. Examples are Moazzem Begg’s approving description of ecstatic Syrians who long suffered Assad’s totalitarianism and torture chambers, Michael Karadjis’ interpretation that “the Syrian revolution returns with a bang,” and statements by the liberal and feminist elements of the Free Syria movement.

Certainly, each perspective contains a degree of truth. My own interpretation from afar lies somewhere between the second (realist) and third (hopeful) arguments, while recognising the fundamental truths of the first: US imperial malevolence, Israeli regional sub-imperialism and Turkish brutality.

The overarching point though is that waging a 13-year long set of diverse struggles by movements with so many fractured elements means many dirty deals were (and are) done. An example is the Kurds of Rojava getting on-and-off protection from Washington while still managing to run a quasi-liberated zone, deservedly famous for progressive advances in social ecology, feminism and municipal-socialist collaboration, in the style of Murray Bookchin’s bottom-up democratic confederalism.

Washington’s interests in having a 1000-strong troop presence in Syria were not to support Rojava, regardless of the Kurds’ role in holding at bay extreme Islamist armies. Trump made clear his reason for betraying Rojava when during a White House meeting he intoned to Erdoğan: “We want to worry about our things [sic]. We’re keeping the oil. We have the oil. The oil is secure. We left troops behind only for the oil.”

Although he is forever committed to resource grabs, Trump has more recently expressed nervousness about the 500 remaining US troops being “caught in the middle,” declaring to Robert F. Kennedy Jr that he wanted to pull them out. The four remaining US army bases in northeast Syria appear to be fully operational.

Also remaining at this stage are the Russian military’s Tartus Mediterranean naval port and Khmeimim air base in western Syria. If the latter were to shut, Moscow’s ability to intervene across Africa in various regional and local conflicts would be hampered, as the alternative for cargo war planes to refuel and reload would be unstable airports in Libya or Sudan.

As for Rojava, early indications are that the Kurdish liberation movement will defend their terrain, in spite of 100,000 refugees now fleeing violence. The Kurds are fighting the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army, which violently captured the city of Manbij — and are also repelling Erdoğan’s ongoing opportunistic attacks. Erdoğan would be furious if an independent Kurdish state emerged from the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, because it would empower progressive Kurdish activists across West Asia, especially in Türkiye.

Statements from Rojava have celebrated Assad’s fall. Yet no one doubts the danger that a full-fledged collapse of Syrian central state power — and, ultimately, a far worse balkanisation and extremist Islamic state — may result from the turmoil. For Syria’s masses, including Kurds and hundreds of thousands who do not yet dare return from exile, the need for solidarity could again become acute.

Sam Husseini explains that different scenarios are possible: “It’s possible that the US and other outside forces will decapitate Syria. And it’s possible that they will keep it technically whole but subservient. Or it’s possible that genuine freedom and dignity will assert themselves there and a new Syria will be a meaningful force for good.”

Hamas, meanwhile, congratulated “the brotherly Syrian people on their success in achieving their aspirations for freedom and justice. We call on all components of the Syrian people to unite, enhance national cohesion, and rise above the pains of the past … Hamas strongly condemns the repeated brutal aggression by the Zionist occupation against Syrian territories and firmly rejects any Zionist ambitions or schemes targeting brotherly Syria, its land and its people.”

The clarity that brave Palestinians provide the world remind us of the interrelationships between geopolitics, political economy and bottom-up solidarity. This is especially critical at a time when even the South African and Colombian governments are failing to meet reasonable expectations to help end genocide.