What the New Deal can teach us about winning a Green New Deal: Part IV—Keeping the pressure on the state

By Martin Hart-Landsberg

September 22, 2019 — Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal reposted from Reports from the Economic Front — Advocates for a Green New Deal, pointing to ever-worsening and interrelated environmental, economic, and social problems, seek adoption of a complex and multifaceted state-directed program of economic transformation. Many point to the original New Deal–highlighting the federal government’s acceptance of responsibility for fighting the depression and introduction of new initiatives to stabilize markets, expand relief, create jobs producing public goods and services, and establish a system of social security–to make it easier for people to envision and support another transformative state effort to solve a major societal crisis.

While the New Deal experience might well inspire people to believe in the possibility of a Green New Deal, the way that experience is commonly presented may well encourage Green New Deal supporters to miss what is most important to learn from it and thus weaken our chances for advancing a meaningful and responsive Green New Deal. Often the New Deal experience is described as a set of interconnected government policies that were implemented over a short period of time by a progressive government determined to end an economic crisis. This emphasis on government policy encourages current activists to focus on developing policies appropriate to our contemporary crisis and on electing progressive leaders to implement them.

In reality, as discussed in Part I, Part II, and Part III of this series, despite the enormous negative social consequences of the Great Depression, it took sustained organizing, led by a movement of the unemployed, to transform the national political environment and force the federal government to accept responsibility for improving economic conditions. Even then, the policies of the Roosevelt administration’s First New Deal were most concerned with stabilizing business conditions under terms more favorable to business than workers. Its relief and job creation policies were minimal and far from what the movement demanded or was needed to meet majority needs.

As I argue in this post, it took continued mass organizing to force the Roosevelt administration to implement, two years later, its Second New Deal, which included its now widely praised programs for public works, social security, and union rights. However, as important and unprecedented as these programs were, they again, as we will see in the next post, fell short of what working people were demanding at the time.

Thus, the most important take-away from this history is that winning a meaningful Green New Deal will require more than well-constructed policy demands and the election of a progressive president. It will require building a left-led mass movement that prepares people for a long struggle to overcome expected state and corporate resistance to the needed transformative changes. And a careful study of the New Deal experience can alert to the many challenges and strategic choices we are likely to confront in our movement building efforts as well as the many policy twists and turns we are likely to face as the federal government and corporate sector respond to our demands for a Green New Deal.

The failings of the First New Deal

The First New Deal, as important and innovative as it was, offered no meaningful solution to the crisis faced by working people. The economy had hit bottom in early 1933 and was beginning to recover. But although national income grew by one-quarter between 1933 and 1934, it was still only a little more than half of what it had been in 1929. Some ten million workers remained without jobs and almost twenty million people remained at least partially dependent on relief.

As discussed in Part III, Roosevelt’s First New Deal relief and job programs, were, by design, inadequate to address the ongoing social crisis. For example, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) did provide the first direct federal financing of state relief. But because the program required matching state funds, many states either refused to apply for FERA grants or kept their requests small. Moreover, because state governments were determined to minimize their own financial obligations and not undermine private business activity, those that did receive relief were subject to demeaning investigations into their personal finances and relief payments were kept small and often limited to coupons exchangeable only for food items on an approved list.

The Civil Works Administration (CWA), created under FERA’s umbrella, was a far more attractive program. Most importantly, participation was not limited to those on relief. And the program offered meaningful, federally organized, work for pay. However, with millions of workers seeking to participate in the program, Roosevelt, determined to keep the federal budget deficit small, refused to fund it beyond six months.

Many workers were also critical of one of the First New Deal’s most important efforts to promote economic recovery: the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA). The NIRA suspended anti-trust laws and encouraged companies to engage in self-regulation through industry organized wage and price controls, and the establishment of production quotas and restrictions on market entry. Workers saw this act as rewarding the same business leaders that were responsible for the Great Depression.

To appease trade union leaders, Section 7a of the NIRA included the statement that “employees shall have the right to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing . . . free from the interference, restraint, or coercion of employers.” Unfortunately, no mechanism was included to ensure that workers would be able to exercise this right, and after a short period of successful union organizing, companies began violently repressing genuine union activity.

Another key First New Deal initiative, The Agricultural Adjustment Act, was also unpopular. It sought to strengthen the agricultural sector by paying farmers to take land out of production, thus lowering the supply of agricultural goods and boosting their price. However, most of the land that was taken out of production had been used by poor African American sharecroppers and tenant farmers. Thus, the policy ended up rewarding the bigger farmers and punishing the poorest.

In short, the programs of the First New Deal, coming almost four years after the start of the Great Depression, fell far short of what workers needed and wanted. And, they did little to slow the on-going mass organizing.

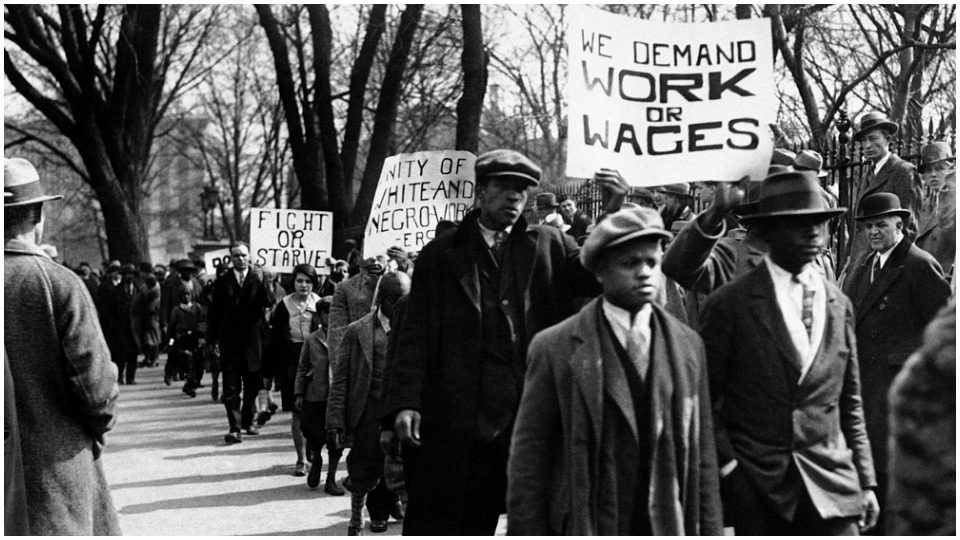

The unemployed movement continues

As described in Part II, the Communist Party (CP) was fast off the mark in organizing the unemployed. As early as August 1929, two months before the stock market crash, it had begun work on the creation of a nationwide organization of Unemployed Councils (UCs). The UCs grew fast, uniting and mobilizing the unemployed, who engaged in locally organized fights for relief and against evictions in many parts of the country. The CP and the UCs also organized several national mobilizations in support of federal unemployment insurance and emergency relief assistance as well as a 7-hour workday and an end to discrimination against African American and foreign-born workers.

The Socialist Party (SP) and the Muste-led Conference of Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) each had their own organizations concerned with the unemployed. But they were few in number and initially not engaged in the kind of direct organizing of the unemployed and direct action practiced by the UCs. SP organizations concentrated on educating the population about the causes of unemployment and the need for national action to combat it. While CPLA organizations did include the unemployed, they were mostly focused on promoting self-help activities for survival. However, beginning in 1933, both the SP and CPLA began to change their approach, and their respective organizations began to operate much like the CP’s Unemployed Councils.

The SP sponsored Chicago Workers Committee on Unemployment began the turn towards direct organizing of the unemployed and a commitment to direct action. By 1933 it had 67 locals in Chicago as well as some in other nearby cities. Committees in other states, primarily in the Midwest, soon followed Chicago’s example. And in November 1933, these more activist committees came together to found a new, Midwest-centered organization, the Unemployed Workers League of America.

The SP’s New York organizations of unemployed were also growing in number. Several came together in 1933 to form the Workers Unemployed League, which later merged with other organizations in the state to become the Workers Unemployed Union. This group eventually merged with groups in other East Coast states to form the Eastern Federation of the Unemployed and Emergency Workers. Socialist Party-led unemployed organizations held multi-state demonstrations in their areas of strength in March 1933 and November 1934 to demand new and more expansive programs of federal relief and job creation.

The Musteites began their own turn to more militant unemployed organizing in early 1933. By July 1933 their Unemployed Leagues (ULs) claimed 100,000 members in Ohio, 40,000 in Pennsylvania, and 10,000 more in West Virginia, New Jersey, and North Carolina. That same month, their ULs formed a national organization to coordinate their work, the National Unemployed League.

The CPLA dissolved itself in December 1933, as activists established a new, more radical organization, the American Workers Party (AWP). Reflecting this change, delegates to the National Unemployed League’s second national convention in 1934 formally rejected the organization’s past reliance on self-help activities and private relief and declared their opposition to capitalism.

The ULs, like the UCs, engaged in mass sit-ins at relief offices to overturn negative decisions by relief officials. One sit-in in Pittsburgh lasted 59 days. They also organized mass resistance to court ordered evictions, blocking sheriffs when possible or returning furniture to an evictees home if it had been removed. ULs in several cities also engaged in direct appropriate of food from government warehouses in line with their slogan, “Give Us Relief, Or We’ll Take It.” The AWP, like its processor, had a strong presence in the Midwest, but was never able to extend its influence or build networks of Uls outside that region.

Not only did the programs of the First New Deal not slow unemployed organizing, the unemployed movement began increasingly taking on a unified national character as unemployed activists from the three different political tendencies gradually began working together, often against the mandates of their leaders. The extent and militance of unemployed activism made it difficult for governments–local, state, and national–to rest easy. For one thing, it highlighted a growing radicalization of the population, as more and more people demonstrated their willingness to openly challenge the legitimacy of the police, the court system, and state institutions.

Relief worker organizing

The First New Deal greatly expanded the number of people on relief, and the CP quickly began organizing relief workers in 1934, followed shortly by the SP and CPLA. The CP sponsored Relief Workers Leagues (RWLs) targeted those receiving FERA relief funds or employed by the CWA. In addition to organizing grievance committees to fight discrimination, especially against African American, single, and foreign-born workers, the RLWs fought for timely payment of relief wages, higher pay for relief work with cost of living adjustments, free transportation to work sites and free medical care, and a moratorium on electric and gas charges for those on relief.

They also sent delegations to Washington D.C. to protest wage discrimination or low wages and organized in support of the CP’s call for a national Unemployment Insurance Bill. Local RWL members also joined with the unemployed in marches on state capitals and on picket lines outside welfare offices to demand more employment opportunities and more money for relief. League members were especially aggressive in protesting against the termination of the CWA.

Nels Anderson, director of Labor Relations for the Works Progress Administration (WPA), provides a good feeling for the work of RWL members:

They parade; they protest; they make demands; they write millions of letters to officials. . . . They are irreconcilable . . . they never stop asking. They state their demands in every conceivable way. They crowd through the doors of every relief station and every WPA office. They surround social workers on the street.

Although not as large or as developed as the unemployment movement, the organization and activities of relief worker organizations were not easy to ignore and made it difficult for the Roosevelt administration to tout the success of its First New Deal initiatives.

Organizing for a national Unemployment Insurance Bill

The CP also continued to organize for a national Unemployment Insurance Bill. The CP and the UCs had declared National Unemployment Insurance Day on Feb 4, 1932 with activities in many cities. It was also the major demand of the second national Hunger March in late 1932. On March 4, 1933, the day of Roosevelt’s inauguration, they organized demonstrations stressing the need for action on unemployment insurance.

Undeterred by Roosevelt’s lack of action, the CP authored a bill that was introduced in Congress in February 1934 by Representative Ernest Lundreen of the Farmer-Labor Party. Not surprisingly, the Workers Unemployment and Social Insurance Bill was strongly supported by the UCs as well SP and Musteite organizations of unemployed. And as a result of the efforts of activists from these and other organizations it was soon formally endorsed by 5 international unions, 35 central labor bodies, and more than 3000 local unions. Rank and file worker committees also formed across the country to pressure members of Congress to pass it.

In broad brush, the bill proposed social insurance for all the jobless, the sick, and the elderly without discrimination, at the expense of the wealthy. More specifically, as Chris Wright summarizes, the bill:

provided for unemployment insurance for workers and farmers (regardless of age, sex, or race) that was to be equal to average local wages but no less than $10 per week plus $3 for each dependent; people compelled to work part-time (because of inability to find full-time jobs) were to receive the difference between their earnings and the average local full-time wages; commissions directly elected by members of workers’ and farmers’ organizations were to administer the system; social insurance would be given to the sick and elderly, and maternity benefits would be paid eight weeks before and eight weeks after birth; and the system would be financed by unappropriated funds in the Treasury and by taxes on inheritances, gifts, and individual and corporate incomes above $5,000 a year. Later iterations of the bill went into greater detail on how the system would be financed and managed.

When Congress refused to act on the bill, Lundeen reintroduced it in January 1935. Because of public pressure, the bill became the first unemployment insurance plan in US history to be recommended by a congressional committee, in this case the House Labor Committee. It was voted down in the full House of Representatives, 204 to 52.

Roosevelt strongly opposed the Workers Unemployment and Social Insurance Bill, and so moved quickly to pressure Congress to write a social security bill he could support. He created the President’s Committee on Economic Security in July 1934, which established the principles that formed the basis of the Social Security Act that was eventually signed into law as part of the Second New Deal.

Trade union organizing

As the economy continued to recover, and the unemployed were increasingly able to find jobs or gain relief, left groups began shifting their attention towards organizing the employed. As one UL organizer who later became an organizer for the CIO explained, the goal was not a permanent organization of the unemployed. “We wanted the day to come when unemployed organizations would be done away with and there would only be organizations of employed workers.”

A number of unions, hoping to build on worker anger over employment conditions and the NIRA’s Section 7a, which many workers were encouraged to believe meant that the President supported unionization, launched lighting fast organizing drives. And with good success. The United Mine Workers was one. For example, it took the union only one day after the NIRA became law to sign up some 80 percent of Ohio miners. And it was able to press its advantage, aided by a series of wildcat strikes, to win gains for its members. The Amalgamated Clothing Workers and the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union also grew quickly, with each winning significant employer concessions following a series of short strikes.

The following year saw an explosion of trade union organizing, including three major successful union struggles. The first was in Toledo Ohio, which at the time was a major center for automobile parts manufacturing. Organizing began in the summer 1933 at several parts plants. In February 1934 some 4000 workers went out on strike. It appeared that the strike would be settled quickly when one of the largest companies, Electric Auto-Lite, decided to oppose any deal. The other companies quickly followed Electric Auto-Lite’s lead and the strike resumed. With Electric Auto-Lite hiring scabs and maintaining production, it appeared the strike was lost. Then, in May, the local UL, the unemployed organization of the American Workers’ Party, intervened.

It organized a mass picket line around Electric Auto-Lite, even though the courts had issued an injunction against third party picketing. The local sheriff and special deputies arrested several picketers, beating one badly. In response, the UL and the union organized a bigger blockade of some 10,000 workers, trapping the strikebreakers inside the factory.

The “Battle of Toledo” was on. In an effort to break the blockade, the sheriff and deputies used tear gas, water hoses, and guns. The workers responded by stoning the plant and burning cars that were in the company parking lot. The National Guard was called out and in the fighting that followed two picketers were killed. Unable to break the strike, the plant was forced to close. After two weeks of Federal mediation, the company and the union reached an agreement: the company recognized the union, boosted its minimum wage, and hiked average wages by 5 percent.

At almost the same time as the struggle began in Toledo, another major union battle started in Minneapolis. In February 1934, the Trotskyist-led Teamster Local 574 organized a short successful strike, winning contracts with most of the city’s coal delivery companies. The victory brought in many new members, both truckers and those who worked in warehouses. In May, when employers refused to bargain with the union, some 5000 walked off their jobs. The union, well prepared for the strike, effectively shut down commercial transport in the city, allowing only approved farmers to deliver food directly to grocers.

The Citizen’s Alliance, composed of the city’s leading business people, tried to break the strike. Police and special deputies trapped and beat several of the strikers. The union responded with its own ambush. The fighting continued over two days. A number of deputies and strikers were badly hurt, some from beatings and some from gunshots; two strikers died. But the strike held. The National Guard was called in an attempt to restore order, and while they brought a halt to the fighting, their presence didn’t end the strike.

Other unions, especially in the building trades, began striking in solidarity with the Teamsters, and the threat of a general strike was growing. After several weeks, with federal authorities applying pressure, the employers finally settled, signing a contract with the union.

A general strike did take place in San Francisco. Passage of the NIRA had, much like in the coal industry, spurred a massive increase in union membership in West Coast locals of the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA). Led by left-wing activists, these locals began, in March 1934, organizing for a coastwide strike to win a shorter workweek, higher pay, union recognition, and a union-run hiring hall. The threatened strike was soon called off by the top East Coast-based leadership of the ILA, following a request from Roosevelt. They then secretly negotiated a new agreement with the employers that met none of the workers demands.

The San Francisco longshoremen rejected the deal and struck on May 9. They were quickly joined by dockworkers in every other West Coast port as well as many sailors and waterfront truckers. All totaled some 40,000 maritime workers stopped working.

Battles between the police and strikers who resisted the employers use of strikebreakers led to injuries in several ports and the death of one striker. Roosevelt tried again to end the strike, but without success. On July 3, employers decided to use the police to break the picket line in San Francisco, and succeeded in getting a few trucks through. They tried again on July 5, leading to a full-scale battle between the police and the strikers. Two strikers were shot and killed on what became known as Bloody Thursday.

On the following day San Francisco longshoreman called for a general strike. Teamster locals in both San Francisco and Oakland quickly voted to strike, despite the opposition of their leaders. On July 14, after a number of other unions had voted for a general strike, the San Francisco Labor Council endorsed the action. Some 150,000 workers went out, essentially bringing the city, as well as Oakland, Berkeley and other nearby municipalities, to a halt. Police tried to break the strike by arresting strike leaders, but the workers held firm. General Hugh S. Johnson, head of the National Recovery Administration, denounced the strike as a “bloody insurrection” and “a menace to the government.”

After three days, city union leadership, fearful of the growing radicalization of the strikers and worried about escalating threats from employers, called off the strike. Local ILA unions were forced to accept federal arbitration, but in October, the arbitrator gave the workers most of what they had demanded.

These struggles showed a growth in worker militancy and radicalism that sent shock waves throughout the corporate community as well as the government. As Steve Fraser explains:

General strikes are rare and inherently political. While they last, the mechanisms and authority of the strike supplant or co-exist with those of the “legitimate” municipal government. . . . Barring actual revolution, power ultimately devolves back to where it came from. But the act of calling and conducting a general strike is a grave one. It may have no revolutionary aspirations, yet it opens the door to the unknown. That these two strikes [in Minneapolis and San Francisco] happened in the same year — 1934 — is a barometer of just how far down the road of anti-capitalism the working-class movement had traveled.

Corporate leaders, as the editors of the American Social History Project describe, did not just roll over in the face of this growing activism:

After the employers’ initial shock over Section 7a had worn off, executives in steel, auto, rubber, and a host of other industries followed a two-pronged strategy to forestall unionization: they established or revived company unions to channel workers discontent in nonthreatening directions, and the vigorously resisted organizing drives.

Textile employers were among the more ruthless in their response. The largest strike in 1934 began in September when 376,000 textile workers from Maine to Alabama walked off their jobs. The employers hired spies, fired union activists, and had workers evicted from their company housing. With the support of a number of governors, they also made use of the National Guard to break strikes. Many strikers were injured in the violence that followed, some fatally. The employers rejected a Roosevelt attempt at mediation and after three weeks, the union leadership ended the strike, having suffered a major defeat.

While a few unions were able to take advantage of the NIRA, most were not. In fact, by early 1935, five hundred AFL local unions had been disbanded. Section 7a’s statement promising workers the right to organize freely turned out to be largely meaningless. It was supposed to be enforced by a tripartite National Labor Board, but the board was given no real enforcement power, and it often refused to intervene in unionization struggles. A number of industries, such as auto, were not even covered by it. By 1935, growing numbers of workers were calling the National Recovery Administration (NRA), which had been established by the President to oversee the NIRA, the National Run Around.

Mounting pressure for a Second New Deal

With his First New Deal, Roosevelt demonstrated a willingness to experiment, but within established limits. For example, he remained determined to limit federal budget deficits and minimize federal responsibility for relief and job creation. Thus, his early initiatives failed to calm the political waters.

Economic improvements, while real, were not sufficient to satisfy working people. Unemployment remained too high, relief programs remained too limited and punitive, and possibilities for improving wages and work conditions remained daunting for most of those with paid employment. Consequently, left-led movements continued to successfully mobilize, educate, and radicalize growing numbers of workers around demands increasingly threatening to the status quo.

Also noteworthy as an indicator of the tenor of the times was Upton Sinclair’s 1934 run for governor of California. His popular End Poverty in California movement advocated production for use and not for profit. Among other things, it called for the state to purchase unused land and factories for use by the unemployed, allowing them to barter what they produced, as well as pensions for the poor and those over sixty years old, all to be financed by higher taxes on the wealthy and corporations.

More right-wing political movements were also gaining in popularity, feeding off of popular disenchantment with government policy. For example, Senator Huey Long from Louisiana criticized Roosevelt for creating huge bureaucracies and supporting monopolization. In 1934 he launched his Share Our Wealth Plan, which called for a system of taxes on the wealthy to finance guaranteed payments of between three to five thousand dollars per household and pensions for everyone over sixty. He also advocated a thirty-hour work week and an eleven-month work-year. His Share Our Wealth Clubs enjoyed a membership of some seven or eight million people, mostly in the South but also in the Midwest and mid-Atlantic states as well.

Frances Townsend, a retired doctor from California, had his own proposal. His Townsend Plan called for giving every person over 60 who was not working $200 a month on the promise that they would spend it all during the month. It also called for abolishing all other forms of Federal relief and was to be financed by a regressive national sales tax. Within two years of the publication of his plan, over 3000 Townsend Plan Clubs, with some 2.2 million members, were organized all over the country and began pressuring Congress to pass it.

Despite political differences, all these movements–at least initially in the case of the movements promoted by Long and Townsend–tended to encourage a critical view of private ownership and wealth inequality and most business leaders blamed Roosevelt, and his First New Deal policies, for this development. They were especially worried about the possibility of greater government regulation of their activities. In 1934, a number of top business leaders resigned from Roosevelt’s Business Advisory Council and began exploring ways to defeat him in the presidential election of 1936.

In sum, by 1935 Roosevelt was well aware that he needed to act, and act decisively to reestablish his authority and popularity. In some ways his decision to launch a more worker-friendly Second New Deal spoke to his limited choices. Most business leaders had now made clear their opposition not only to his administration but to any new major federal initiatives as well. In fact, in May 1935, the Supreme Court ruled the National Industrial Recovery Act unconstitutional. It did the same with the Agricultural Adjustment Act in January 1936.

A do-nothing policy was unlikely to win back business support or strengthen Roosevelt’s political standing given the economy’s weak on-going economic expansion. Thus, as Steve Fraser comments:

The Roosevelt administration needed new allies. To get them it would have to pay closer attention to the social upheavals erupting around the country. The center of gravity was shifting, and the New Deal would have to shift with it or risk isolation.

Roosevelt’s response was the Second New Deal. His political acumen is well illustrated by the fact that the three signature achievements of the Second New Deal—the Works Progress Administration, the National Labor Relations Act, and the Social Security Act–not only responded to the demands of the mass movements organized by left political forces, but did so in a way that allowed him to take back the initiative from the left.

The Works Progress Administration, created in May 1935, provided meaningful work for millions of jobless workers, satisfying the demands of many of those in the unemployed and relief workers movements. Moreover, unlike the earlier short-lived CWA that focused on public construction work, the Works Progress Administration also included a Federal Arts Project, a Federal Theater Project, a Federal Writers’ Project, and a Federal Music Project.

The National Labor Relations Act, passed in July 1935, created a framework for protecting the rights of private sector workers to organize into unions of their choosing, engage in collective bargaining, and take collective actions such as strikes. Many trade unionists celebrated this act, believing that it would secure their rights to organize. The Social Security Act passed in August 1935 established a system of old-age benefits for workers, benefits for victims of industrial accidents, unemployment insurance, and aid for dependent mothers and children, the blind, and the physically handicapped. This was a direct response to the demands of the broad workers’ movement for a federally organized system of social protection.

However, as we will see in the next post, while the Second New Deal represented a major step forward for working people, each of these signature initiatives, as designed, fell short of what progressive movements demanded. Unfortunately, changing political and economic conditions greatly weakened the left over the following years, leaving it unable to sustain its organizing and its pressure on the state. As a consequence, not only was there no meaningful Third New Deal, the reforms of the Second New Deal have either ended (direct public employment), greatly weakened (labor protections), or come under attack (social security).

Lessons

The New Deal was not a program conceived and implemented at a moment in time by a government committed to transformative policies in defense of popular needs. Rather, it encompassed two very different New Deals, with the Second far more progressive than the First. Moreover, the Second New Deal did not emerge as a natural evolution of the First New Deal. Rather as shown above, it was a largely a response to continued popular pressure from movements with strong left leadership.

This history holds an important lesson for those advocating for a Green New Deal. It is unlikely that popular movements can win and secure full implementation of their demands for a Green New Deal at one historical moment. Rather, if we succeed, it will take time. However, as the history of the New Deal shows, the process of change is not likely to be advanced by advocating for modest demands in the belief that these can be easily won and that governments will be predisposed to extend and deepen the required interventions over time. Rather, we need to build awareness that our political leaders will most likely respond to our efforts with reforms designed to blunt or contain our demands for change. Thus, it is necessary to put forward the most progressive demands that can win popular support at the time while preparing movement participants for the fact that the struggle to win meaningful transformative policies will be long and complex.

Another lesson from the New Deal experience is that movement building itself must also be a dynamic process, responding and transforming in response to political and economic developments. It was the movement of unemployed that spearheaded the political pressures leading to the First New Deal. First New Deal policies and the economic recovery then changed the organizing terrain, leading to new organizing of relief workers and trade unions.

At the same time, there were strong threads tying these movements together. One of the most important was that experiences in one, say the unemployed movement, provided an educational experience that helped create organizers able to spur the work of the newer movements, for example that of relief workers. And because of all these movements owed much to the work of left political groups, there was a common vision that also tied them together and encouraged each to support the struggles of the other and join in support of even bigger demands, such as for a new system of social insurance.

Advocates of a Green New Deal need to pay careful attention to this organizing experience. Given the Green New Deal’s multidimensional concerns, achieving it will likely require organizing in many different arenas which may well require, at least at an early stage, organizing a number of different movements, each with their own separate concerns. The challenge will be finding ways to ensure coordination, productive interactions and interconnections, and an emerging unified vision around big transformative demands.