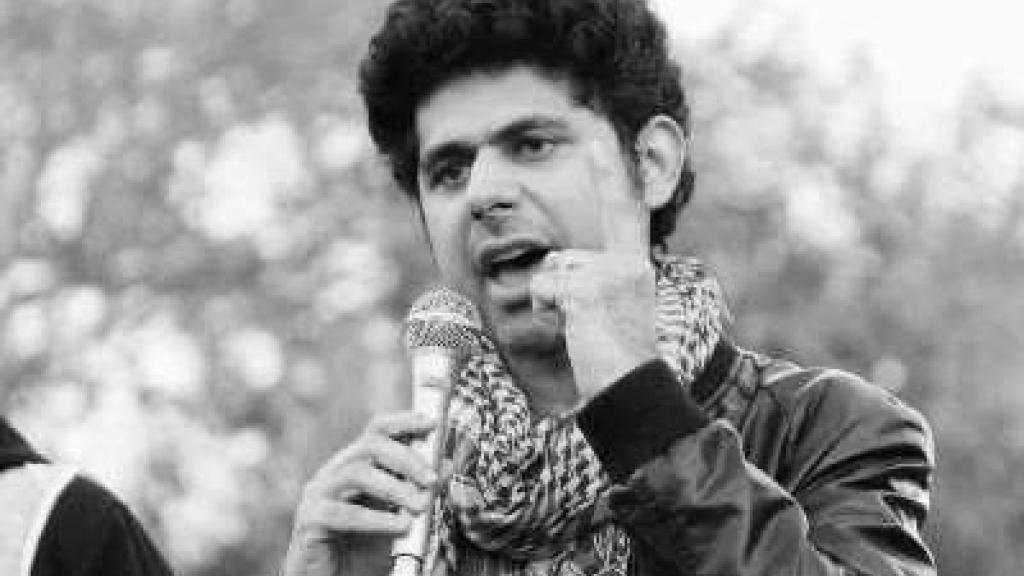

Ammar Ali Jan (People’s Rights Party, HKP): ‘You have to embed yourself in the movement of history’

First published at Progressive International.

Tanya Singh talks to Haqooq-e-Khalq Party (People’s Rights Party, HKP) co-founder and Progressive International (PI) Council member Ammar Ali Jan about the challenges of building a new workers’ party in Pakistan — and the HKP’s recent victories for Lahore’s most vulnerable workers.

The HKP has existed for two years now. What has the experience been like and what were some of the challenges in building the new workers’ party in Pakistan?

A few things moved us in the direction of setting up a party.

One, the old left that still existed, despite its glorious past, had lost its vitality, its energy. It had become more of a nostalgic hub for old comrades rather than something that looked towards the future. And the old contradictions and internal fights were carried into the present.

The second was that other left groups were very much inclined towards the immediate gratification of social movements. You know, there's this belief that the working class as a subject will spontaneously arrive on the stage of history — an eruption that will carry forward the organization of the left. We have a very strong critique of that idea. We don't think social movements necessarily lean to the left or the right. In fact, they are as inclined to move towards the right as they are to the left. The existence of social movements implies that there is some kind of a void in the situation, some kind of a gap. But they are not necessarily projects of the right or the left.

As we know from the Arab Spring and many other movements that have emerged in the last decades, the political content of a movement is defined by organizations that are anchored in the masses. The Muslim Brotherhood, the military and other groups that had a presence amongst the people — they were the ones who were able to give direction to society after the eruption of the movement in the streets. What's more important than waiting for a social movement is to do the work — the organizational work, the work of building institutions — prior to any such social eruption, and then political strategizing after. With that understanding, we changed our method and we started organizing deeply within working-class communities. That was another major difference that we had, that we wanted to build institutions and have a sustained presence among the working class.

The third is a question of subjectivity. We did not feel that oppositional politics alone were enough. We also had to present an affirmative narrative and an affirmative program. We needed to delineate a strategy towards achieving that program — towards winning. What that requires is understanding the movement of history at a given conjuncture, seeing what possibilities arise out of it, and using the existing tendencies of history to pursue the political projects that you want to pursue. You have to embed yourself in the movement of history. For that, we were very clear that we needed to build a program on which we can fight elections. And this is what was lacking after the fall of the Soviet Union — on the Pakistani left, you either had anarchist types saying, “everything around the world and everything that's happened on the history of the left is wrong”, or you had those who were nostalgic. I think we needed to overcome both.

Can you tell us about your recent workers' conference in Lahore?

In the last year and a half, we contested elections from this working-class area. Our primary motivation for running was that we wanted to build a base among the working people.

It has been a long time since the left has actually built a base in any industrial, working-class area. In the election, we got 2.5% of the vote. But the more important thing was that we built linkages that had been absent for a very long time because the left had turned into a very small group of alienated intellectuals. This was an attempt to form that connection between ideas and the people. And we managed to build a workers’ office. We managed to build a health clinic. We managed to build a training centre. And through that, we started engaging with workers from the industrial area — factory workers.

The minimum wage last year in Pakistan was PKR 32,000, which today would mean about $120 per month. These workers were getting PKR 16,000, or $60. That was, of course, a major scandal. But the workers had no clue what to do about it. They didn't know that there was a labor department that was being paid to look after them. So we organized the workers. And we ended up winning a government intervention. We got their wages increased from PKR 16,000 to 23,000, which was the biggest jump since 2001.

This year, again, the government announced that the minimum wage would rise to PKR 37,000. And then there was another round of education that the workers did. And one of the people who really stood out as a leader of the workers was this young man, Maulana Shahbaz — a worker and a religious cleric. He's a very interesting character. For a very long time, he was telling people to accept their fate as given to them by Allah. We have to bear this pain, the suffering. But all of this was a facade because he and others knew that they had very limited options. So they had to console themselves. But the moment they realized that there was a party now that was willing to take a stand with them — a party with lawyers, intellectuals, and contacts in the media — they transformed.

Working class movements always produce their own leaders. They have their own organic leadership that understands the problems of the workers, and the details that cosmopolitan intellectuals can never understand. And they connect in a very direct way with workers. But they need some kind of backing from people who they know will stand with them in difficult times. So this guy started organizing. The word started spreading and we are now active in about eight to ten factories across Lahore and more recently in Gujranwala. We were involved in a strike as well. And in every place we won victories and an increased minimum wage: Shekhara, Gujarawala and a few factories in Faisalabad. We're expanding our work like that.

Recently, we decided to bring all these workers together for a labour conference. Maulana Shahbaz, I should mention, is from the Chawla factory and the labour conference brought together workers from there, as well as Infinity Engineers and power loom workers. These are people who were not used to giving speeches and were not used to setting agendas. But we made sure that they had the stage. They were the ones leading the event. And it was beautiful to see the kind of clarity that they displayed in explaining their situation. For example, one of the workers said that it's interesting that whenever the notification of a rise in the minimum wage comes, it takes months before the government can implement it. And sometimes it's not implemented at all. Workers have to fight for it to get implemented. But when a notification about an increase in petrol prices comes, it is implemented within hours. So when you want to snatch money from the working class, that happens in a second. But when you want to give something back, that's impossible.

These kinds of sentiments are related to the inflation problem that's hitting Pakistan, including the problem of the IPPs [Independent Power Producers], which is a big working-class issue. You have these IPPs — independent investors who were encouraged to set up power plants — and you have what are called capacity payments. One of the problems with that scheme was that the money that was being paid to these independent power projects was in dollars. And the second thing is they had to be paid whether they produced electricity or not, for the capacity of generating electricity that they had. If I'm an investor, I'll just set up a power plant. Whether I produce much electricity or not, whether the government buys my electricity or not, they will have to pay. And how will the government pay? Back in the day, they were just taking loans from banks. But eventually, the government had to return those loans. And how do you return those loans? You can't tax the military. You can't tax the corporate elites. You can't tax the landed elites. You can't tax the banks. So you just put it all on the consumer. It ended up becoming a scam and it has devastated households.

I have been hearing about the electricity costs in Pakistan, which have been enormous, going into thousands and thousands of rupees. And with the minimum wage that you mentioned, it must be impossible for workers and their families to pay them back.

Basically, the country, even the middle class, has defaulted. The working class is now living totally on the edge. They are taking food away from hungry people to subsidize the IPPs and other corporate elites. At this point, it's a calculation by the state about how many people can they afford to let die. It's social murder. The nutritional values have gone down. About 40% of kids are now stunted. There's a 40-41% poverty rate, which has gone up from 30%. It's basically de-development. Over 40% of our budget is going to repay loans. It's total extortion from the masses.

All these things were discussed at the conference. Maulana Shahbaz was one of the main people who spoke and spoke really well. The next day he was fired from the factory. And that's what triggered our campaign. The workers found out about 15 minutes later. Within another five minutes they stopped their work and came out in solidarity. This was unprecedented, and the workers staged a sit-in which continued for over a week.

The owner tried to kick all the workers out of the hostels as well. So we had multiple fights: One to sustain the unity of the workers at the dharna [sit-in]. Then we had to defend their homes. And then we also had to create enough of a buzz on social and other media so that the factory owners felt pressured. Very fortunately, we were able to do all of that. We had found out in the negotiations with the Chawla factory that they were planning to shut down the factory for a few months. They hoped to kick out Maulana Shahbaz and then kick out everybody else and give them the PKR 23,000 minimum wage as severance.

But the negotiations that we led after this fight led to the highest golden handshake in the industrial area since at least the seventies. That's what we're being told. So those who have been given PKR 23,000 will now be given anywhere between two lakh to a million [717 to 3600 USD] depending on how much service they've done. That has really increased the confidence of the workers.

Yeah, and I think organizing such conferences helps in party-building because it boosts confidence of not just the workers but also the people in HKP.

I've also been reading about the sit-ins and the protests and HKP's assistance in organizing them. Have there been any specific strategies that HKP has adopted to ensure compliance from employers, while also protecting workers from further retaliation from these employers?

That's the million-dollar question. One of the strategies is that we have a major working-class leader who I think is probably the most important trade union leader right now in Pakistan. His name is Baba Latif, President of the Punjab chapter of HKP.

He never completed his schooling and comes from a very humble background, but he is one of the fiercest orators, activists and labour leaders. And he's the one who has won these victories over the last few weeks. So he was central. Maulana Shahbaz is another person into whom we are putting a lot of our time.

The party's job is to stand with the leadership of the working class and to work with them so that they start becoming the leadership of HKP. If the HKP is to become a representative of the working class, then it must have in its leadership a sizable number of working-class leaders who have a mass following. Now, of course, in terms of understanding the problems of the workers and connecting with them, these working-class leaders have both experience and a natural gift. But the party can also help them operate at a different level, which is to say that many of them don't understand the language of the law, many of them aren’t necessarily oriented towards the left. They come from their own particular ideological backgrounds. Many of them have not been part of political organizations. So there are things that we can help them with. But this is never a one-way process. It's a two-way process where they are teaching us more. Eventually, the purpose of this collaboration has to be the development of working-class leadership. And I think that is a big, big step that we've taken with people like Baba Latif and Maulana Shahbaz.

Now, we need to have more reading groups for the workers. To fight the chamber of commerce, which is united against us, we need a strong legal team. We need a much stronger social media network. And then we need to increase the numbers. One of the things that we were constantly reiterating during the sit-ins is that workers have to start thinking of themselves as being connected to other workers. So it's not just individual factories. That's one of the reasons why we did the labour conference — so that workers from different factories come together and see the similarities. If you have the numbers on your side, then the pressure is enormous on the administration, because it's not easy to arrest people when you have hundreds of them fighting over something like the minimum wage, right? The minimum wage is such a sensitive issue. If any government arrests people for demanding the minimum wage announced by the government, it becomes a problem. And that was our line throughout.

How is HKP engaging with student movements in Pakistan? Have you witnessed any challenges in building bridges between workers and young intellectuals in Pakistan?

Historically, this huge challenge. Up until the eighties, there was a very close link between intellectuals and the working class. There are always tensions between intellectuals and working-class leaders. That's normal and natural. Contradictions are productive. So for example, many working class people tend to be socially very conservative. But then we have, amongst intellectuals, feminist organizers. And you can't do this kind of populism where you appeal to the chauvinism of the workers. Similarly on the other side, workers are very good at organizing mass activity. And on many occasions, they think that doing study circles or reading groups on frivolous issues like Stalin versus Trotsky is a waste of time. And I think they're probably right on that. However, that's a productive tension. Both sides learn from each other. We teach them something, they teach us something.

I don't think it's a scandal to say that we all come from different social backgrounds. The point of a political project is to bring people together behind a shared purpose. The point isn't that you come from the same social origins because the same social origins can produce both fascists and communists. You want the professionals, you want the sympathetic industrialists, you want the sympathetic media, you want the sympathetic students, you want the sympathetic workers. All these forces come together to form the working-class movement. That's always been the case everywhere.

But what happened after the fall of the Soviet Union is that the communist parties collapsed and many people went into the NGO sector. And then their language and their way of communicating with people completely changed. And the way they framed the issues was basically dictated by the US embassies — the funding agencies were framing the entire discussion. As a result, it's very difficult for a lot of our intellectuals to even sit in a working-class meeting and not get perpetually offended. The gap has become too high. And right-wing groups have started to fill the vacuum.

I know that similar things have happened in India. In Mumbai, for example, the entire working-class movement in the textile industry was replaced by Shiv Sena. Many of the families turned right-wing. It's happening in West Bengal as well with a lot of communist areas voting for the BJP [Bhartiya Janata Party]. That has happened throughout history. When the working class movement collapses, the right fills that gap. That has to be changed. And we're trying. We have to have the patience to cross this wall between intellectuals and workers, a wall that is much higher than the Berlin Wall. And we have to show the commitment to learn and unlearn a lot of things if we want to move forward.

We don't have to worry too much about winning an intellectual argument with any international left force. Our point has to be about building working-class leadership. Of course, to build a global left, you need to have ideas. You need to have consistency. Ideas are important. But ideas have density and gravity only when they're anchored in the masses.

I was reading about the provincial governments in Pakistan collaborating with the International Labor Organization (ILO) recently on a unified labour code, which got rejected because it had a lot of anti-labor policies. I was wondering if HKP has any alternative proposals, where they do want to safeguard workers' rights and also address the concerns that were raised in the current draft.

This labour code was an attempt to cripple the already-weak trade union movement.

It is a race to the bottom, with the government thinking and the ILO thinking that this will facilitate global capital. The problem is that at PKR 23,000, it's kind of like paying people for an eight-hour workday in bread. You can't really call it a life because there's really nothing these people can do. They can't even travel across Lahore. They have to save for three months to travel across the city they live in. And yet the ILO and the government are under the impression that we need to make labor even more flexible. That's the language that they use.

Our proposal is the total opposite of this. We rejected the uniform labour code because it's an assault on the working class. We propose that, first of all, we need stronger labor departments. The labour departments are not implementing labour laws, including the minimum wage, social security, the EOBI [Employee’s Old Age Benefits Institution], which is the pension, and they are totally in the pockets of the Chamber of Commerce. Labour departments are functional across the country. They're one of the most expensive departments. And yet they're not able to implement even the basic minimum wage. And that's a problem. If the labour departments become more active, that would be a huge boost to the labour movement.

The second thing is we need a proper survey of factories. This has been a long-standing demand of the trade unions to ensure that there are unions in factories. Interestingly, all factories legally are bound to have trade unions. They're bound to have the minimum wage, they're bound to have social security, a pension, all of that. And, criminally, they all show these things to exist on paper. That means that across Pakistan, what you have is this facade. There has to be a proper audit — a proper accountability drive — to ensure that you have trade unions in the factories.

And then the structure that we've proposed is that there should be a tripartite system where the government, the industrialists and elected trade unionists sit together at the table and decide how to implement laws. And that is an essential aspect of taking industrial policy forward. You cannot just work your workers to death. You need to have workplace democracy, you need to have a state that serves workers. And if you have complete authoritarianism — I would say barbarism — within the factory gates, then you're not a democratic society. Because if the everyday experience of workers in Pakistan — the majority of our society — is one of fear, terror and brutal exploitation, then that will reflect itself in the culture. It will express itself in the political domain.

We also have a larger industrial plan that we've been pushing for a while, which says that Pakistan has deindustrialized prematurely. We stopped investing in industry and we went towards land speculation and other speculative ventures very quickly. And this was linked to the imperialist wars in the region. Pakistani elites were very happy that quick money and quick dollars were coming from the US. We became addicted to those dollars and we used those dollars for speculative investments in land, in mineral resources, in banks, in stocks. That took away from any kind of serious planning of the real economy and industrial production.

So the de-industrialization that is happening in Pakistan is not because of workers demanding the bare minimum, it is because the elites have chosen to speculate and gamble their way into the billionaire club. Many of these elites have massive properties in Dubai now. Pakistanis are the second most propertied class in Dubai right now. So they'd rather do that than pay a minimum wage to their workers. That shows you that the problem is not the workers. The problem is the elite, which has decided that it's going to spend on short-term benefits rather than planning for the long term. But the state has to invest in the long term. And long-term planning means re-industrializing Pakistan. Here, workers are not part of the problem, they are part of the solution.