The declining rate of profit: Déjà vu all over again — A rejoinder to William Jefferies

I am thankful to William Jefferies for responding to my article “Marx was wrong about the declining rate of profit. Isn’t it time we put this false idea to rest?”. His reply, “Was Marx wrong about the declining rate of profit?,” has helped sharpen the focus of discussion. His critique is also a good example of how to engage in a well-mannered exchange.

In this rejoinder, I will not rehash my original article. Readers should read the original and not rely solely on William’s response. Likewise, readers should read William’s response and not rely on this rejoinder. The principal aim here is to focus readers’ attention on a distilled version of my original article’s essential or substantive argument. I will try to clarify it below. In addition, I will address some of William’s arguments in a way that, I trust, will help clarify relevant questions that arise from Karl Marx’s Capital.

My main criticism of William’s article is that it does not address the substantive argument of my article. A secondary criticism is that William seems to misunderstand what investment spending means, which takes him into a confusing and unnecessary discussion of productivity. A third disagreement concerns causality.

However, before we get to my criticisms, I want to say a few words about reading Capital’s third volume, which I also urge readers to do. In fact, I underscore this plea, as if with a very large black felt-tipped pen. Do not rely on secondary sources alone, as these are more often than not the source of intergenerational misinterpretation and confusion.1 Be especially wary of interpretations uttered bombastically.

Capital Volume III

It is a huge mistake to read Marx biblically. It is similarly obtuse to read Marx retrospectively; to try to excavate his work for salient quotations with which to support or criticise one or another 20th or 21st century conceit. Both errors expect of Marx greater perspicuity (and perspicacity) than could ever have been possible. This is especially relevant to Capital Volume III. As its editor, Friedrich Engels had to contend with four serious obstacles.

The first concerned both he and Marx, namely the growing practical workload involved in their leadership of the First International. Secondly, illness hampered Marx’s work on the third volume (Engels, Vol 3, Preface, 1894 [1981], pp. 92-3):

At several points both handwriting and presentation betrayed only too clearly the onset and gradual progress of one of those bouts of illness, brought on by overwork, that made Marx’s original work more and more difficult and eventually, at times, quite impossible. And no wonder! Between 1863 and 1867 Marx not only drafted [volumes 2 and 3] as well as preparing the finished text of Volume I for publication, but he also undertook the gigantic work connected with the foundation and development of the International Working Men’s Association. This is why we can already see in 1864 and 1865 the first signs of the illnesses that were responsible for Marx’s failure to put the finishing touches to Volumes II and III himself.

Thirdly, it was only long after Marx’s death in 1883 that Engels was able to complete the work involved in dictating Marx’s original notes and their transcription, translation and editing. Engels, too, was nearing life’s end. He had “been worried by persistent eye trouble, which … for years reduced … working on written material to a minimum” and precluded almost all work under artificial light. Age was also inflicting its imperious punishments in other ways. “After one is seventy”, he bemoaned, “the Meynert fibres of association in the brain operate only with a certain annoying caution, and interruptions in difficult theoretical work can no longer be overcome as quickly or as easily as in the past.” Finally, and most importantly, all Engels had to work with was a “partly incomplete” and “hurriedly drafted first elaboration”. In particular, Engels drew attention to the fact that, as each section of the volume “went on, the draft would become ever more sketchy and fragmented, and contain ever more digressions on side issues that had emerged in the course of the investigation” (Engels 1894 [1981], pp. 91-3, 1027).

Despite Engels’s editing and helpful insertions (for Chapter 4, which is mandatory reading), the third volume is both exceedingly repetitive and often unclear. At times, it is brilliant. Its philosophical rumination on the nature of capitalism is profound. However, its economic thinking is now 160 years old. Its specifically economic subject matter was evolving, and has evolved subsequently, at a phenomenal rate. It preceded the insights we got from modern national-income accounting (and business accounting, too2). It preceded the revolution in macroeconomic thought that occurred in and after the 1930s by more than 70 years. In these respects, it is anachronistic.

Hence, it is reasonable to cut Marx and Engels some slack. On the other hand, it is equally reasonable to scrutinise central propositions clearly set out in Volume III. This is especially so when some thinkers today hold fast to those that are demonstrably false.

Gardening

Again, before we get to the matter of substance, I must correct what I fear is a misunderstanding by William of investment spending. Clearing this up should help in understanding my main argument. William interprets3 what I had said as follows:

Provided the rate of investment (spending on circulating capital) is higher than spending on fixed capital then the rate of profit will rise. But circulating constant capital, essentially raw materials, no more has the ability to create value than fixed capital does. The value of circulating constant capital is merely reproduced in the product. Only circulating variable capital (wage labour) has the ability to create more value than it itself costs, but this distinction is not mentioned here. [Michał] Kalecki conflates variable capital with circulating capital, effectively returning to Adam Smith. This is in any respect largely beside the point for Kalecki’s critique of the law of falling profits.

To be clear, investment spending for most part is spending on fixed capital. Investment for most part is not “spending on circulating capital … essentially raw materials”. Investment spending means spending by enterprises on means of production, the output of Marx’s Department 1. However, there is a distinction between spending on fixed and circulating means of production. Fixed investment means spending on long-lived capital assets that re-enter production only incrementally over time (buildings, plant, equipment, machinery, electro-technology, energy infrastructure, etc). This is the national-accounting item gross fixed capital expenditure. It is also the annual addition to the gross fixed capital stock.4 Means of production also include raw materials and intermediate goods, circulating capital in Marx’s terms. Because these re-enter production rapidly and re-emerge in finished consumption and capital goods, investment spending on them includes only the change in their stocks. This avoids the problem of double-counting their value, which has been included already in the annual value of the finished products of Department 1 (fixed capital goods or means of production) and Department 2 (consumer goods).

Hence, because investment is spending on fixed constant capital for most part, not circulating constant capital, I (qua Kalecki) do not “conflate variable capital with constant capital”. I have tried to understand the point William is trying to make and suppose it has something to do with his mistaken identification of investment and raw materials. Therefore, his reductio ad absurdum inversa of my argument (qua Kalecki) to Smith was bewildering. As for the good Reverend Thomas Malthus, I was both bewildered and amused.5

In summary, investment spending is largely spending on fixed capital. The stock of fixed capital that investment creates by accumulation is the denominator of the rate of profit.

Substantive argument

Any substantive criticism must directly address the essential argument of its target. Unless it does, readers cannot take a critique to be telling. It is a comment, perhaps, or a thought piece (or some such). For a critique to be a critique, and not something else, it must demonstrate that the essential object of its criticism is flawed. For these reasons — quite separately from those in the preceding section — I hope that I have been fair in criticising Capital Volume III’s case that the tendency of the rate of profit to fall was inevitable. Perhaps impertinently, I ask critics of my article to attend to its central points in similar fashion. As I said above, I think that William has not done so. The substantive argument is as follows.

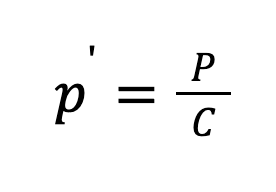

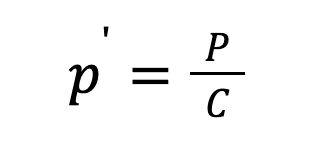

It begins with a precise definition of the average or aggregate rate of profit p’. It is equal to the flow of gross profits P over a year divided by the stock of accumulated capital C at a point of time in the year, say year’s end.6 That is:

A stock is a point-in-time measure like one’s bank balance. A flow measures comings and goings over time, say of one’s income and expenses. The distinction between stocks and flows is fundamental. The average, aggregate or social rate of profit is just the percentage return P (flow) on the value of accumulated capital C that enterprises have invested in — or have tied up in — means of production (stock).

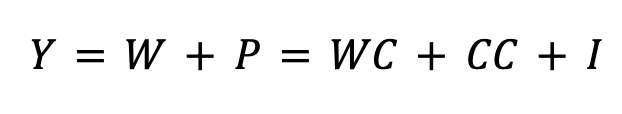

In the simplified world in which Marx deduced a declining rate of profit, we must abstract from government and the rest of the world.7 Hence, the aggregate value that production adds each year Y will always resolve into flows of wages W and gross profits P (or, if you prefer, flows of variable capital V expended as wages and gross surplus value S).8 Incidentals aside, Y also resolves into aggregate spending by working families WC and capitalists CC on consumer goods plus aggregate investment spending by enterprises I on means of production.9 That is:

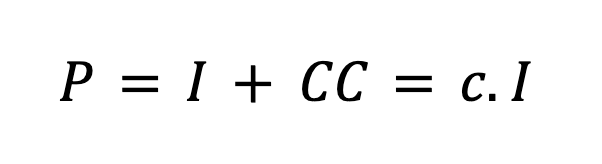

Now, in Marx’s simplified world, working families do not save. Therefore, we can represent the numerator of the rate of profit as:

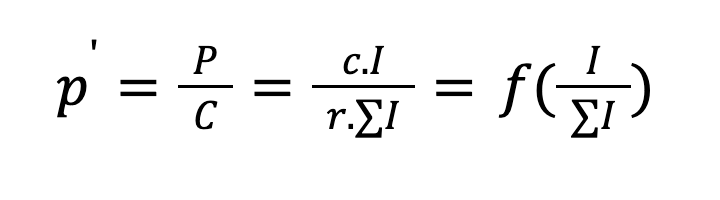

Given this, the essence of the argument is very straightforward. In fact, once we have established the identity P = c.I, then the rest is just arithmetic. If it is reasonable to suppose that CC is less significant than investment and/or closely relates to it, it follows that the rate of profit is quantitatively a function of investment spending. Investment is the biggest and, surely, the most dynamic part of the numerator P. Its accumulation each year adds to the denominator. Making allowance r for retirements of physically and technologically exhausted means of production and insignificant working capital cash holdings, the denominator C is just the accumulated gross stock of past annual investments I.10 It is obvious that the relationship between the flow of investment to its accumulated stock lies at the heart of the profit rate or vice versa.

Now, the percentage relationship of each year’s investment to the capital stock — essentially the relationship of I to sigma I, the sum of past investments adjusted by r — we know as the rate of accumulation.

Therefore, the argument is simply that the rate of profit and the rate of accumulation are functionally integrated. They move together. If we abstract from capitalists’ consumption, capital stock retirement and working capital — which Marx was wont to do — the rate of profit is the rate of accumulation and vice versa. This, too, is obvious from the foregoing arithmetic. Now for the punchline (no numbers, just the logic of the argument): Given the intimacy between the rate of profit and the rate of accumulation, a decreasing rate of profit will express a decreasing rate of accumulation.

What did Marx say? He said the opposite: “A fall in the profit rate, and accelerated accumulation, are simply different expressions of the same process. Accumulation in turn accelerates the fall in the profit rate…”11 Let us set aside the word “accelerate” — just use “rising” and “falling”, “increasing” and “decreasing”. The foregoing arithmetic tells us that a rising rate of accumulation is necessary for a rising rate of profit and vice versa; that is, a falling rate of profit is necessary for a falling rate of accumulation. It is just arithmetic: one necessarily goes with the other. Shall they be sufficient for each other? That all depends on the factors c and r. Revaluation also plays a role. What is certain, however, is that each is the beating heart of the other. That was what the three figures in my original article demonstrated. Marx was wrong.

Now, observant readers get a bonus for noticing that I have not made Kaleckian causality a condition of satisfaction of the essential argument above (hence all the “each others” and “vice versas”). The sufficient condition for satisfying the argument is just the one involving the identity P = I + CC = c.I. That is, it is the arithmetical equality — not necessarily the direction of causality — that counts in determining the validity of Marx’s tendency. Readers familiar with national-income accounting might have inferred this, but here I make the point about the identity more explicit.

Of course, causality is indispensable for understanding how capitalist economies function (and everything else in the world, for that matter). I will return to William and causality shortly. For now, let us just put the conclusion this way: Marx was wrong, independently of causality.12 The content of this section, then, is the argument that a critic must refute.

Relevance

We should pass over in silence what William says towards the end of his contribution concerning capital stock measurement. He offers some interesting but, in some cases, overreaching thoughts. However, these are beside the point. My allusions to Dante’s circles of hell and the Cambridge Controversies signalled why I was not going to go there in my original article. Nothing turned on it. This discussion was for another time and place. I called it an abyss to emphasise the point. The references that I added aimed merely to help those who might want to stare into it.

Moreover, I made it clear that my contribution was not an empirical exercise. Perhaps naively, I appended one possible rendition of an empirical rate of return merely to indicate that the undulating shape of the rates in the preceding three figures was not from Mars. Far from committing myself to any trend, I was at pains to point out that mine was an exercise concerning the logic of Marx’s argument. That is why, for example, I maintained faith with Marx’s own formulations concerning capital-stock revaluation (the devaluation of constant capital, if one prefers). As it happens, I have reservations about both the conceptual and practical possibility of measuring and valuing the fixed capital stock, but that, too, is beside the point.

What is not beside the point is the error William makes when he says that “The tendency of the rate of profit to fall does not rest on the ratio between flows and stocks, but between living and constant capital.” William here tries to refocus readers’ attention on his (and Marx’s) main contention that labour-saving capital accumulation (the replacement of living labour with past labours embodied in machines, etc) must ultimately reduce the rate of profit. He says “…labour is not a manufactured commodity, so the expansion of surplus value is limited relative to the accumulation of constant capital, which is unlimited. Therefore, there will necessarily be a tendency over time for labour to be displaced by constant capital, for the organic composition of capital to increase, and for the rate of profit to decline.”

The argument is a version of Marx’s13 — that is, living labour is the source of all profits (numerator). However, the sum of living (conceived, gestated, born and matured) human labour cannot arrive ready-made as if by immaculate fabrication. Accumulation, by contrast, can endlessly increase the fixed capital stock (denominator). The ratio of one to the other, therefore, must fall. The trouble with William’s rendition is that the numerator is still a flow and the denominator is still a stock. The tendency of the rate of profit does still rest on the ratio between its very particular flow P and its very particular stock C. How the one is constrained to relate to the other is not a matter of abstract speculation but arithmetical logic — precisely the question at hand.

I do not want to overemphasise the stock-flow point, since it is possible that William might like to reformulate it. However, I do want to emphasise the following. If the rate of profit is equal to the flow of gross profits P over a year divided by the stock of accumulated capital C at a point of time in the year:

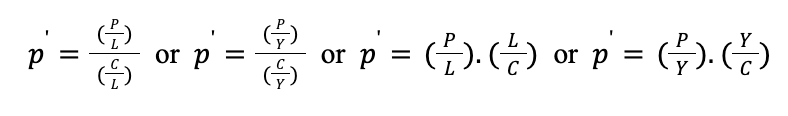

then, to state the argument negatively, anything that does not contribute to the exhaustive determination of P or C is irrelevant. What about the ratio of the flow of profits to the annual flow of living labour L, the labour-value form of Y? Surely, it is important? This is the labour-value profit share of value added. What about the ratio of capital to living labour? This is the labour-value capital to output ratio, the inverse of the commonly used output-capital ratio. It is the one that William emphasises, a concomitant of Marx’s organic composition of capital. We might then reimagine the rate of profit as the ratio of these two ratios:14

The trouble is that, despite being important in their own right and highly relevant otherwise, the profit share and the output-capital ratio play no determinative roles here. Given that we can already explain p’ exhaustively in terms of the investment-profit identity and the accumulation of past investment spending (capitalists’ consumption and retirements acknowledged), the L and Y variables are redundant to this calculation. The problem is not just that the terms cancel arithmetically in the above expressions. The problem is that they do not add explanatory value. As paradoxically as it might seem, they are as irrelevant to the task as would be the number of runners in the 2024 Melbourne Cup.15 All we need are the numerator, the denominator and their determinants. Occam’s Razor actually works in this instance.

Marx’s formulation of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall in terms of the rate of exploitation and the value composition of capital failed both for this reason and because he handled stocks, flows and turnover inadequately.16

Causality

Now, Kalecki17 adds to the foregoing an essential ingredient, one that really should be obvious. This is the causally determinative role of investment spending. This role is consistent with the causally determinative role of spending in general. Aggregate or effective demand engenders aggregate supply or production. We do not live in the world imagined by David Ricardo and Jean-Baptiste Say, which assumes that production ultimately creates its own demand. Rather, production adjusts to the level of spending. This is macroeconomics 101, to flog the dead cliché.

Unfortunately, I am afraid that William makes something of a meal of causality. He says:

For Kalecki, capitalist spending creates profits — “capitalists get what they spend.” Surplus value therefore originates from capitalist demand, not capitalist demand from surplus value. Capitalist consumption of luxury scrambled egg, smoked salmon and caviar creates the luxury scrambled egg, smoked salmon and caviar; they eat it before it is put on the plate. The causality is the wrong way round. The amount of capitalist spending does not determine the amount of profit, the amount of profit determines the amount of capitalist spending. Capitalists have their profits before they spend them, not after.

Two problems with this passage stand out. First, it misunderstands what Kalecki meant about causality. Demonstrating the result does not deny how that result comes about. To say that aggregate investment and capitalists’ consumption spending causes the level of aggregate profits is just to say that a corresponding level of aggregate production of capital and consumption goods must adjust to that level of spending. It is not to say that spending conjures profits ex nihilo, out of thin air. Production has to occur. The wheels of industry have to spin. Goods and services must hit the market and find buyers. Capitalists do not eat the scrambled egg of production before it hits the plate. The scrambled egg hits the plate because the waiter receives an order (demand) and takes it to the kitchen (fixed capital stock). The kitchen staff (labour) gathers the ingredients (circulating capital), does the cooking, scrambling and garnishing with parsley (production). The waiter returns with the egg-on-plate and the bill (more circulation). The egg-eater (consumer) pays in order to settle accounts (realisation). At the end of the day or week or whatever, the restaurant adjusts its orders of eggs, bread, milk and parsley so that it has neither grumpy unfed customers nor piles of rotting food.

Secondly, it is simply wrong to say — or at least to imply — that the “amount of profit determines the amount of capitalist spending.” Retained gross profits, represented in large measure by accumulated depreciation provisions, are just one part — internal financing — of the resources an individual capitalist might call upon for investment spending. External financing via debt, new share issues and so on provides an independent and crucial resource for the individual capitalist. In the aggregate, however, if both investment spending and capitalists’ consumption were forced to “come out of” realised gross profits, then expanded reproduction could not happen. In value and price terms, aggregate retained gross profits cannot set a limit. If it did, perpetual simple reproduction should be the best result. We should say goodbye to accumulation forever. In Marx’s limiting case, capitalists cannot even call upon borrowed workers’ savings because there is none. Rather, aggregate accumulation must rely additionally on some form or other of external financing and, ultimately, on some form or other of credit creation.18

Conclusion

To deny the causal macroeconomic priority of aggregate (effective) demand is to return us to the antediluvian pre-1930s world of Ricardo and Say. I am not saying that William is in denial. What I am saying is that, once one accepts the causal priority of demand, rigour demands consistency. Likewise, once one accepts the necessity that both the numerator and denominator of the rate of profit are functions of investment spending, the rest — including the impossibility of Marx’s tendency of the rate of profit to fall — is just arithmetic.

References

Doughney, James 2025a, ‘Marx was wrong about the declining rate of profit. Isn’t it time we put this false idea to rest?’, LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal, 29 March. https://links.org.au/marx-was-wrong-about-declining-rate-profit-isnt-it-time-we-put-false-idea-rest

____ 2025b, ‘Surplus profits, capital exports and imperialism: An interrogation of commonly held beliefs and assumptions’, LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal, 9 February. https://links.org.au/surplus-profits-capital-exports-and-imperialism-interrogation-commonly-held-beliefs-and-assumptions

____ 2016, “Problems in Marx’s Theory of the Declining Profit Rate”, in Courvisanos, Jerry, James Doughney and Alex Millmow eds., Reclaiming Pluralism: Role of History of Economic Thought in Heterodoxy—Essays in Honour of John E. King, London, Routledge.

Eatwell, J., M. Milgate and P. Newman eds. 1987, The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, London, Macmillan.

Howard, M.C. and J.E. King 1992, A History of Marxian Economics: Vol. II: 1929-1990, London, Macmillan.

____ 1989, A History of Marxian Economics: Vol. I: 1883-1929, London, Macmillan.

____ eds. 1976, The Economics of Marx: Selected Readings of Exposition and Criticism, Harmondsworth, Penguin.

Jefferies, W. 2025, ‘Was Marx wrong about the declining rate of profit? William Jefferies responds to James Doughney’, LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal, 11 April. https://links.org.au/was-marx-wrong-about-declining-rate-profit-william-jefferies-responds-james-doughney

Kalecki, Michał (1933, 1934, 1935 [1971], Selected Essays on the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy: 1933-1970, Cambridge UK, Cambridge University Press.

Keynes, J.M. 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Macmillan, London.

Mandel, E. 1981, “Introduction”, K. Marx 1894 (1981), Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. III. F. Engels ed., trans. B. Fowkes, Penguin/New Left Review, London.

Marx, K. 1867 (1976), Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol I, trans. B. Fowkes, Penguin/New Left Review, London.

____ 1885 (1978), Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol II. F. Engels ed., trans. D. Fernbach, Penguin/New Left Review, London.

____ 1894 (1981), Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol III. F. Engels ed., trans. B. Fowkes, Penguin/New Left Review, London.

____ 1857-8 (1973), Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy (Rough Draft), trans. M. Nicolaus, Penguin/New Left Review, London.

____ 1861-3, Theories of Surplus-Value, vols. I (1963), II (1968) & III (1971), Progress Publishers, Moscow.

Marx, K. and Engels, F. 1844–95 (1975), Selected Correspondence, third edition, Marx to Engels, 11 July 1868, Progress Publishers, Moscow.

Shaikh, A. 1987, “Organic Composition of Capital”, in The New Palgrave: Marxian Economics, pp. 304-9, from Eatwell, J., M. Milgate and P. Newman eds. 1987, The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, London, Macmillan.

- 1

Works in the history of economic thought by Mike Howard and John King are notable exceptions (e.g. eds. 1976; 1989, 1992).

- 2

Lest one is tempted to disagree with this point, one should first consult Marx’s letters to Engels asking him to clarify business accounting concepts and practices. See for example Marx to Engels, September 11, 1867 (Selected Correspondence 1844-95, Moscow 1975, p. 181). For his interest in what was then quaintly called ‘Italian bookkeeping’ (double-entry bookkeeping), see Marx to Kugelmann, July 11, 1868 (Selected Correspondence, p. 197); Theories of Surplus Value (1861-3 [1968], vol. 2, pp. 48, 155; [1963] vol. 1, p. 399). Double-entry bookkeeping was not extensively practiced until the second half of the 19th century.

- 3

I also fear that William sometimes confuses Kalecki and me. I am entirely responsible for the argument in “Marx was wrong about the declining rate of profit. Isn’t it time we put this false idea to rest?”. Kalecki is responsible for the profit equation and its causality. It is to me that the references to Kalecki in the following quote should apply.

- 4

The annual deduction from the stock is retirement. Accumulation of the gross stock is investment less retirement, allowing for revaluation. Accumulation of the net stock is net investment (gross investment less depreciation), allowing for revaluation.

- 5

I also confess confusion over William’s comments on productivity. These seem to miss the point that I tried to make in the original article concerning Marx’s attitude to the (de)(re)valuation of fixed capital, that productivity advances in Department 1 reduced the socially necessary labour time required to reproduce or replace the capital stock (aka its value). All I can suggest to readers is to refer back to my original article.

- 6

See Engels, addition to Capital, Vol III (1984 [1981], p. 334): “(The rate of profit is calculated on the total capital applied, but for a specific period of time, in practice a year. The proportion between the surplus-value or profit made and realized in a year and the total capital, calculated as a percentage, is the rate of profit. And so this is not necessarily identical with a rate of profit in which it is not the year but rather the turnover period of the capital in question that is taken as the basis of calculation; it is only if this capital turns over precisely once in the year that the two things coincide...)”.

- 7

See “Surplus profits, capital exports and imperialism: An interrogation of commonly held beliefs and assumptions” (Doughney 2025, LINKS, 9 February) for a comprehensive account that includes government and the rest of the world. https://links.org.au/surplus-profits-capital-exports-and-imperialism-interrogation-commonly-held-beliefs-and-assumptions

- 8

The transformation problem — how to reconcile labour-value metrics and market prices if profit rates equalise — is a problem for another day. Let us just suppose, as Marx did, that prices and values transform proportionally at the aggregate level. “For the analysis now following we can ignore the distinction between value and price of production, since this disappears whenever we are concerned with the value of labour’s total annual product, i.e. the value of the product of the total social capital.” (1984 [1981], p. 971; see also pp. 273, 323)

- 9

In modern terms, we have the standard four-part national-accounting identity: aggregate effective demand (spending or expenditure) = gross domestic product (production or GDP) = national income = value added. Gross here means before deducting estimated depreciation expenses.

- 10

That is, before deducting provisions for depreciation from C and depreciation expenses from I.

- 11

Marx, Capital, Vol III (1894 [1981], p. 349). “We have seen how it is that the same reasons that produce a tendential fall in the general rate of profit also bring about an accelerated accumulation of capital…” (1894 [1981], p. 331). See also (1894 [1981] pp. 324-5, 326, 344, 357-9, 361, 364-8); Grundrisse (1857-8, [1973], pp. 749-50).

- 12

I shall take up the subject again in a forthcoming article on over-accumulation.

- 13

Reprised in similar form by Ernest Mandel (1981, p. 31) and Anwar Shaikh (1987).

- 14

Of course, Marx uses variants of these ratios in his formulation of the tendency. See Doughney (2016) for a rendition in consistent stock-flow labour-value forms. Unfortunately, this work sits behind an expensive paywall. I will try to make its content accessible. Shaikh (1987) makes particular reference to these ratios.

- 15

The number being 23.

- 16

Doughney (2016).

- 17

Kalecki beat John Maynard Keynes to the punch in the 1930s, articulating the decisive macroeconomic role of effective demand. He did so in Polish, alas, not the lingua franca, so to speak, of that time or this. See Kalecki (1933, 1934, 1935 [1971], Part I, pp. 1-34). This is not to deny decisive importance to Keynes (1936). There are some obvious similarities between my article “Marx was wrong about the declining rate of profit. Isn’t it time we put this false idea to rest?” and Kalecki (1933).

- 18

As I put it in ‘Surplus profits, capital exports and imperialism: An interrogation of commonly held beliefs and assumptions’ (Doughney 2025, LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal, 9 February https://links.org.au/surplus-profits-capital-exports-and-imperialism-interrogation-commonly-held-beliefs-and-assumptions): “It is also essential to grasp the simple fact that capital investment spending is not constrained causally by profits. Another way of saying this is that profits are not causally prior to capital investment spending. Investment, so to speak, does not come ‘out of already earned profits’. On the contrary, capital investment can be externally credit-financed, in whole or in part. Moreover, credit-financing is causally independent of saving by other sectors. Households, for instance, do not have to save in order that corporations can invest. Access to credit also means that investment spending will include but not be bound by corporations’ internal-financing, the application to investment of firms’ internal financial assets. In particular, investment is not necessarily bound by the quantity of those financial assets that correspond to accumulated depreciation provisions. It is not that firms do not apply accumulated depreciation to new or capacity-replacing investment. They do. It is that they do not necessarily have to. A telling criticism of Mandel (1975) by Bob Rowthorn (1976, p. 64, emphasis added) makes just this point. The quotation is long but worthwhile: ‘During an expansionary phase, there is a very high level of investment which, Mandel [1975] says, is financed out of reserve funds already in existence when expansion begins; these funds, he argues, were built up in the course of several industrial cycles, during the preceding non-expansionary phase of the long wave. In the non-expansionary phase, capitalists have an excess of capital which they place in reserve funds; later, when expansion begins, they use these funds to finance a large-scale investment programme. This argument is mistaken. Once expansion gets under way, it is self-supporting; profits are high and provide a sufficient flow of money to finance investment on the required scale; capitalists then have no need for the “historical reserve fund of capital” on which Mandel lays so much stress. The only time when such a reserve might be necessary is in the initial stages of expansion, before profits have started to flow on a large enough scale to finance investment. But, even then, there is an alternative source of finance, namely bank credit. When expansion begins economic prospects are good, anticipated profits are high and banks are prepared to lend, confident their loans are secure. Thus, firms can finance their initial investment by borrowing from the banks. Later, as profits start to flow, they can use their own internally generated funds. Now the key point about bank credit is that it can increase total purchasing power in the economy. Banks are not merely a funnel through which other people’s savings are channelled. They can actually create new purchasing power…[and] can provide investment finance in excess of what has already been saved by capitalists or anyone else. When they do this, banks are not lending reserve funds built up in the previous non-expansionary phase of the long wave. They are creating genuinely new purchasing power! Mandel has fallen victim to a well-known fallacy, that no one can lend what they, or someone else, has not already saved. The peculiar characteristic of banks is that they can do just this.’”