Marx was wrong about the declining rate of profit. Isn’t it time we put this false idea to rest?

A recurrent theme in Marxian economics since the early 20th century has been “surplus capital”. It has become a shibboleth, a sticky notion more taken for granted than analysed. My recent contribution to LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal sought to dispel it and offer readers some help in navigating their way through often incoherent debates on the economics of “imperialism”. 1

A related shibboleth, so I shall argue, is the declining rate of profit. The shibboleth goes something like this: on the one hand, profits accumulate massively; on the other, declining rates of profit mean that investment opportunities fall. Pent up “surplus capital”, much like hot air in a whoopee-cushion, must find release. It blurts out offshore and into various forms of unproductive rent-seeking.

In the hope of clarifying some questions raised in today’s debates about capitalism and imperialism, the variant of the decline in the rate of profit upon which I shall focus is Karl Marx’s seminal theory. In short, this theory holds that the competitive imperative to accumulate capital causes the consequent decline in the return to it, namely its rate of profit. The work of the late Ernest Mandel exemplifies this line of thought, but it also appears in the work of David Harvey.2 The latter summarised it in the Socialist Register (2004, p. 63) in a contribution on the “new” imperialism:

The way I sought to look at this problem in the 1970s was to examine the role of “spatio-temporal fixes” to the inner contradictions of capital accumulation. This argument makes sense only in relation to a pervasive tendency of capitalism, understood theoretically by way of Marx’s theory of the falling rate of profit, to produce crises of overaccumulation. Such crises are registered as surpluses of capital and of labour power side by side without there apparently being any means to bring them profitably together…[W]ays must be found to absorb these surpluses.

Marx’s profit theory was deterministic, in the sense that capital ultimately has no choice other than to accumulate an ever-increasing mass of profits (or surplus value) in an ever-increasing stock of capital assets: machinery, plant, equipment, buildings, computing paraphernalia, inventories and so on. Each year’s investment spending by firms on assets such as these, which re-enter the production process each subsequent year until they retire, is the engine of accumulation. Even if they export capital offshore and indulge in evermore fantastic rent-seeking schemes, firms still must relentlessly accumulate at home to protect the value of the previously accumulated stock (Marx 1894 [1981], pp. 351-2, see also p. 361):

It should never be forgotten that the production of this surplus-value — and the transformation of a portion of it back into capital, or accumulation, forms an integral part of surplus-value production — is the immediate purpose and the determining motive of capitalist production... This is the law governing capitalist production, arising from the constant revolutions in methods of production themselves … and from the general competitive struggle and the need to improve production and extend its scale, merely as a means of self-preservation, and on pain of going under.3

Monopolistic tendencies might dampen competition, but the requirement to keep up with technological progress and reap the benefits of scale economies remains. Indeed, technically speaking, monopolies arise from accumulation. The productivity derived from capital-intensity and scale reduces unit costs and prices and thereby undercut actual or potential rivals. Margaret Thatcher’s TINA phrase comes to mind: there is no alternative but to accumulate, even for monopolies.4 Marx insisted that individual capitalists were subject to “external and coercive laws” that forced them to keep extending “capital, so as to preserve it…by means of progressive accumulation” (1867 [1976], p. 739; emphasis added). However, over the long run, the coercive laws were bound to deliver diminishing returns. Ups and downs notwithstanding, the rate of profit should decline as the rate of accumulation increases or, in Marx’s terminology, accelerates. Counteracting tendencies, such as capital devaluation and a decrease in the share of newly produced value received by workers, moderate the decline but do not negate its inexorable trajectory.

The theory is plausible, not to say compellingly reassuring for socialists. The rate of profit is the vital sign of capitalism’s health. Its decline is inescapable because capital must accumulate. Capitalism, therefore, fetters its own development and causes its own eventual demise. Alas, for all that, the theory that accelerated accumulation of capital must eventually cause the profit rate to decline is simply wrong. Careful attention to Marx’s exposition of the theory in Capital, the Grundrisse and elsewhere demonstrates that the theory is not coherent in its own terms. Indeed, to emphasise this point, this contribution argues its case in Marx’s terms and against his own criteria of judgement.

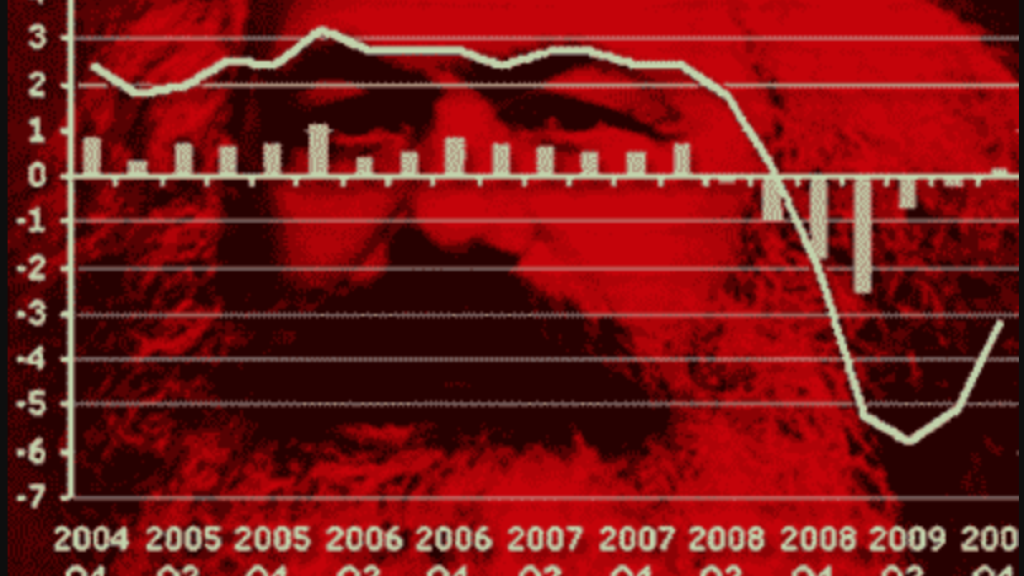

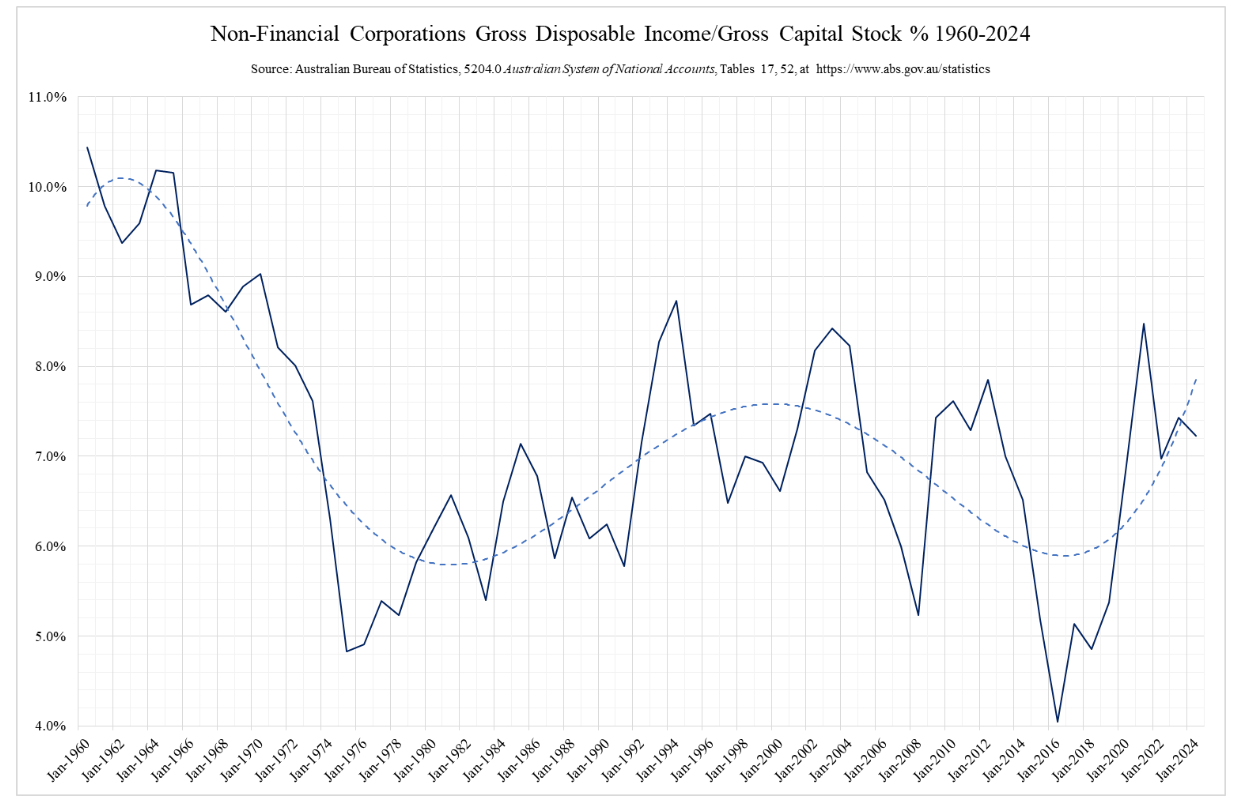

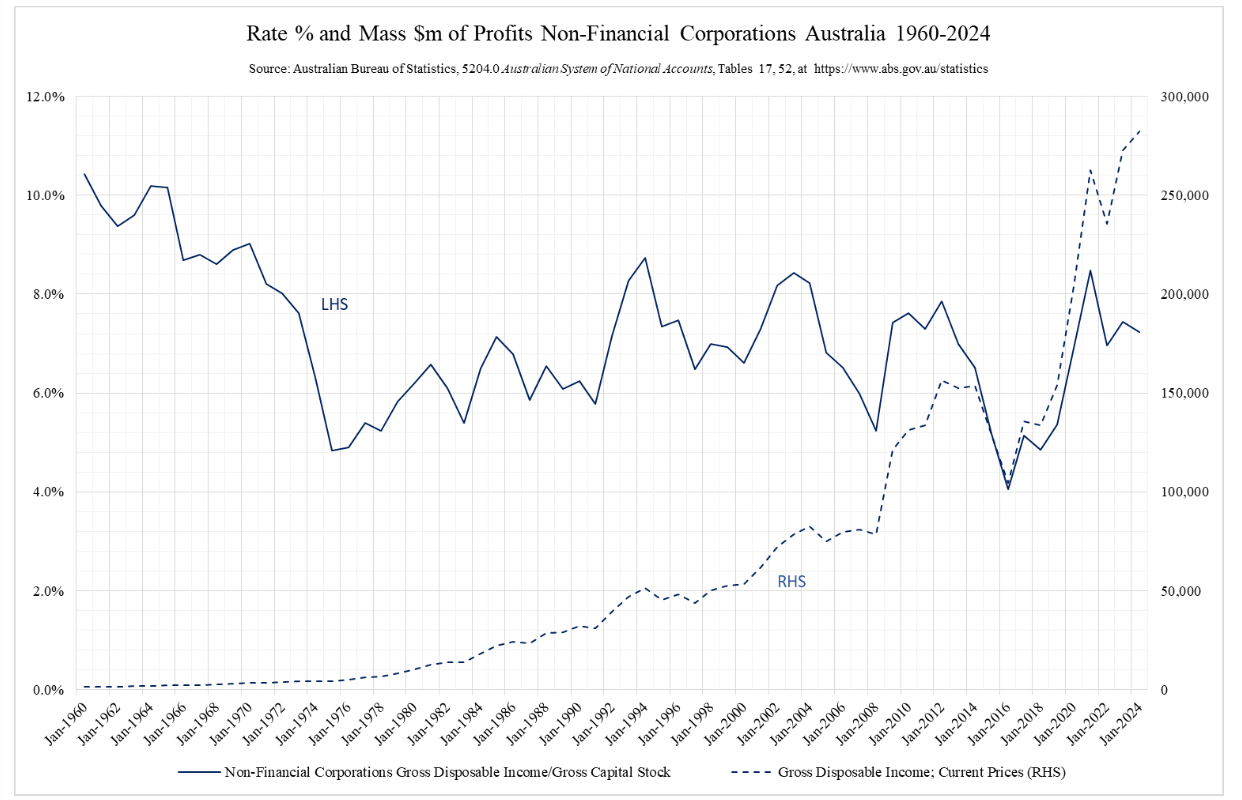

In case of possible misinterpretation, however, it is well to be clear at the outset that this is not an empirical exercise. Rates of profit do fall and rise, as illustrated in Appendix Chart A1. Nor will the exercise involve peering into the abyss concerning the very nature and measurability of profits and capital.5 In addition, in case there is any doubt, I am not questioning the idea that capitalism will be its own gravedigger; that is, if it has not dug humanity’s grave first. The point of the present article is simply to demonstrate the logical impossibility of Marx’s declining-profit-rate formulation. A by-product of the demonstration is to invalidate the underconsumption variant of the theory as well.

The pathway to these conclusions runs through the groundbreaking work of the Polish economist Michał Kalecki (1899-1970). Kalecki’s rigorous causal reasoning about how the capitalist economy functions helps us to understand why. In particular, Kalecki focuses our attention on effective demand or aggregate spending. Especially important is the role of capital investment spending in the determination of profits.6 First, however, it is necessary to understand Marx. Then we can turn our attention to Kalecki’s insights.

Marx’s theory

Theorists have long looked here and there in Capital for nuance. Nuance they have found. Marx recognised that crises might involve disproportions between sectors and industries and the inability to realise produced profits. Spending might fall short in time or place. Marx also recognised that squeezes on profits might occur because labour shortages had enabled workers to obtain higher wages.7 Marx was a voracious fact hound. He could not but sniff out such nuances.

Nuance conceded, a fair reading of Marx’s work must still force one to acknowledge that “The Law of the Tendential Fall in the Rate of Profit” (Capital, vol. 3, chapter 13) was dominant. He described it in the Grundrisse notebooks of 1858-9 as “in every respect the most important law of modern political economy” (1858-59 [1973], pp. 748-9). Marx’s notebooks of 1861-3, which we know now as the Theories of Surplus-Value, rehearsed formulations of the law. He formalised these in the 1864-5 drafts of the third volume, which Engels edited and published in 1894, and in the first volume, of 1867. I make these points to emphasise that there is no evidence that he ever either questioned the theory or its role in the ultimate demise of capitalism.

Rather, in a letter to Engels in 1868, he stressed that “The tendency of the rate of profit to fall as society progresses…follows from what has been said in Book I [Capital, Volume 1] on the changes in the composition of capital following the development of the social productive tendencies. This is one of the greatest triumphs over the pons asinorum of all previous economics.”8 Reflecting on the failures of Adam Smith and David Ricardo, in particular, Marx (1894 [1981], p. 319) noted that “not one of the previous writers on economics succeeded in discovering [the law/tendency]…These economists perceived the phenomenon, but tortured themselves with their contradictory attempts to explain it.” Specifically, Marx thought that Smith and Ricardo were right that the rate of profit would decline over time but were wrong about causes. Their error was to seek causes in nature rather than in social productive tendencies.

To Marx’s mind, the same cause — namely the competitive pressure to increase the social productivity of labour by accumulating capital-intensive labour-saving technology — would at once increase the social mass of value and profit and, inexorably, reduce its average rate. The mass of profit, surplus value or surplus labour, is the difference between the total value of labour expended in production and the necessary labour required to produce sustenance for workers and their families, sometimes called the wage-goods bundle. The rate of profit, on the other hand, is the ratio of surplus labour (mass of profit or surplus value) to the value of the mass of accumulated labour tied up in the means of production (the capital stock).

To permit greater logical accountability, we should represent all this symbolically with clear definitions. Let P be the annual flow of social or total surplus value or profit (surplus labour or the labour time not paid in wages) and W the annual flow of value obtained by workers (social necessary labour, the time paid for in wages and consumed to sustain working families). The total annual value added Y is the sum of W and P (necessary plus surplus labour). The average social rate of profit, on the other hand, is the ratio of the annual flow of surplus value or profits P divided by the accumulated value of labour tied up in the stock of capital C advanced for production. This stock principally comprises fixed capital, with inventories of raw materials and cash working capital representing a diminishing proportion.9 Marx’s simplified industry structure10 comprises Department I, which produces capital or investment goods I, and Department II, which produces consumption goods for workers WC and capitalists CC.

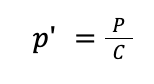

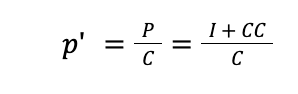

From this, two straightforward equations arise within Marx’s framework. These are all we need. The first represents the rate of profit:

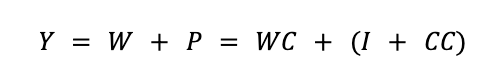

The second represents the annual value added in production Y:

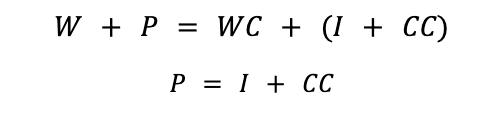

Now, if workers spend all of their wages on the wage goods bundle, as Marx assumed that they should11, then it must be the case that the remaining spending (investment spending I, or the output of capital-goods industries, plus capitalists’ consumption CC) is equivalent to P. In other words, W and WC cancel, so that:

The gross capital stock C will grow each year by the value of investment or capital-goods spending I, and thus, in the first instance, we can elaborate the gross rate of profit as:

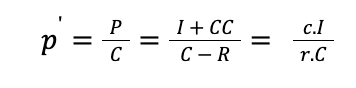

To account for the fact that a portion of the capital stock retires each year, we can indicate the proportion that remains as r. Similarly, c indicates the increase to the numerator caused by capitalists’ consumption. Hence, we can elaborate the profit-rate expression more precisely as:

Marx’s argument was that the profit rate should fall despite the effects of two significant countervailing or counteracting tendencies. The first counter-tendency was an increase in the rate of exploitation, in effect the ratio of social surplus value or profits P to wages W.

The second was the constant devaluation of the stock of fixed capital C. The value of current plant and equipment declined because increasing productivity in Department I made it cheaper to replace or reproduce in terms of money and labour time.12 Marx was distinctly modern in rejecting historical-cost accounting (that is, using the unadjusted price paid for capital goods at the time of their purchasing). In addition, enhanced productivity and crises should cause faster retirement and even destruction (“forcible devaluation”13) of some existing capital, thereby facilitating periodic jumps in the profit rate.

Marx’s claim reduces to a very simple proposition. It is that the rate of growth of the denominator c.C of the elaborated equation must, over time, exceed the rate of growth of the numerator P = c.I, ups and downs and counter-tendencies notwithstanding.

Kaleckian reformulation

As Kalecki asked of the numerator (P = I + CC = c.I): “Does it mean that profits in a given period determine capitalists’ consumption and investment, or the reverse of this?” Kalecki’s answer to his own rhetorical question brooks no causal ambiguity. The determination “depends on which of these items is directly subject to the decisions of capitalists. Now, it is clear that capitalists may decide to consume and to invest … but they cannot decide to earn more. It is, therefore, their investment and consumption decisions which determine profits, and not vice versa.” (1971, pp. 78-9)14 That is, the causality runs from spending by capitalists on Department I’s output plus their own consumption of part of Department II’s output to their profits P. In a nutshell, capitalists get what they spend.15

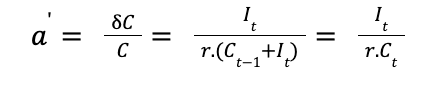

As the following will reinforce, the critical variables are investment I and the capital stock C, and C is principally investment spending accumulated. The rate at which the capital stock has grown to the end of period t is the rate of accumulation a′.

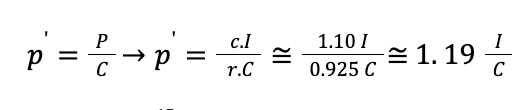

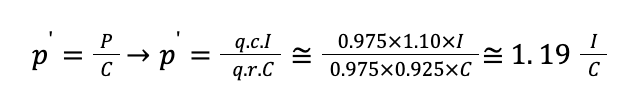

If it is reasonable to think that both capitalists’ consumption and retirement move in reasonably constant proportion to I and C, respectively, then (with numbers added for illustration16):

It follows that, given some starting rate p′,17 the trend in the rate of profit p″ is fundamentally a function of the rate of change of investment i″ = δI/I (the numerator) and the rate of capital accumulation a′ = δC/C (the denominator). The denominator is clearly consequent upon (that is, a catch-up function of) the rate of change of investment i″.

Therefore, it is possible to simplify the terms in which we consider the direction of the profit rate and, ergo, the logical burden Marx’s theory must bear, according to:

Plainly, this is just to say that the profit rate will rise if the rate of change of investment i″ is greater than the rate of accumulation a′, and vice versa. Another way of saying this is that investment is growing proportionately by more than is the stock of capital. In the limiting case, in which capitalists do not consume and none of the capital stock retires, the rate of profit and the rate of accumulation will be equivalent.

Marx’s errors

The logical burden of the above expression shows why Marx’s theory breaks down irretrievably. Keep in mind that the burden arises from Kalecki’s insight — which, in turn, his reading of Marx and Rosa Luxemburg had influenced18 — that profits are just what capitalists themselves spend. Once we understand the imperious necessity that the denominator of the rate of profit must be understood to be a function of its numerator, and that the numerator is a function solely of capitalists’ spending decisions, then two determinations must also follow as a matter of logical (indeed arithmetic) necessity. A third is that theories of a declining profit rate due to working-class underconsumption fail because workers’ consumption does not figure in the calculation at all.

The first determination is that both major counter-tendencies that Marx proposed will not materialise. Capitalists might squeeze necessary labour and wages to the point of working class “immiseration” — to the point that workers “were able to live on air”19 — but it would not increase the rate of profit one iota, as odd as that may seem. To be sure, squeezing wages will reduce aggregate value added because wage-goods spending will fall. Hence, the size of Department II will shrink. For the same reason that underconsumption theories fail, it is apparent that a wage-squeeze or a profits-squeeze will not directly affect profits or the accumulated capital stock (the two constituents of the profit rate). Falling or rising wages will, other effects remaining equal, change the wage and profit shares of national income, but they will not directly affect the profit rate.

Moreover, because the two constituents of the profit rate are manifestations of the value of the material output of Department I, both the numerator and the denominator of the profit rate will devalue at the same rate; that is, in line with Department I’s increased productivity in a given year. Why? Just as Marx valued labour power over time in accordance with productivity changes in Department II,20 we should value profits according to productivity changes in Department I. Just as we devalue the capital stock denominator in this way at year end, including that part added by investment over the year, we must devalue that same part in the numerator. It is about revaluing what capitalists have already spent over the year according to what that spending is worth in dollars current at the end of the year. If our yardstick is spending to maintain production capacity then, in Kaleckian terms, the relative value of this year’s required investment spending, and the profits consequent upon it, should be reckoned to have fallen with the cheapening of constant capital.

Again, as odd as it may seem, if capitalists’ consumption maintains its proportionality with investment spending, the profit rate will be unaffected by devaluation.21 Accounting for the role of devaluation q, which affects numerator and denominator separately but not the rate of profit per se, we now have (with numbers illustrating a 2.5% productivity gain):

The second necessary consequence of Kalecki’s insight is far more devastating for Marx’s theory. In chapter 15 of Capital Volume III, Marx offered a nuanced account of the law, including its own internal contradictions. Nonetheless, he underscored its theoretical importance by reprising formulations made famous in the Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859) concerning the fettering of capital by immanent barriers of its own making. He also articulated why Smith and Ricardo had strained their minds to find a natural not economic explanation of their own conclusions that the profit rate should decline over time. It is worth reading a long selection to establish how the various parts fit and, therefore, how we should judge the law (1894 [1981], p. 349-51):

A fall in the profit rate, and accelerated accumulation, are simply different expressions of the same process, in so far as both express the development of productivity. Accumulation in turn accelerates the fall in the profit rate, insofar as it involves the concentration of workers on a large scale and hence a higher composition of capital… Thus economists like Ricardo, who take the capitalist mode of production as an absolute, feel here that this mode of production creates a barrier for itself and seek the source of this barrier not in production but rather in nature (in the theory of rent). The important thing in their horror at the falling rate of profit is the feeling that the capitalist mode of production comes up against a barrier to the development of the productive forces which has nothing to do with the production of wealth as such; but this characteristic barrier in fact testifies to the restrictiveness and the solely historical and transitory character of the capitalist mode of production; it bears witness that this is not an absolute mode of production for the production of wealth but actually comes into conflict at a certain stage with the latter’s further development… It should never be forgotten that the production of this surplus-value — and the transformation of a portion of it back into capital, or accumulation, forms an integral part of surplus-value production — is the immediate purpose and the determining motive of capitalist production.22

The first point to note is that, implicit here is the antediluvian — that is Ricardian and pre-Kaleckian, pre-Keynesian — idea that causality runs from profit to capital-spending and accumulation (“transformation of a portion of it back into capital”). The idea is also implicit in the circuits-of-capital schema of capital’s self-expansion (M—C—M’ = [M+m]) that Marx introduced in the first volume of Capital. While the realisation of profit and its conversion back into capital via investment seems a plausible explanation at the level of the individual capitalist firm, the explanation does not hold at an economy-wide or macroeconomic level. The level of spending or effective demand causes production to be what is and not vice versa. It is true that Marx was aware of effective demand. He rejected “Say’s Law”23, which, in effect, maintained that production naturally engendered its own purchases. Say claimed that this precluded generalised overproduction. Marx explained, immediately after the passage quoted above, that a “second act”, of realisation of surplus value through sales, must complete the process started in the “first act”, of production. The two acts were not harmonious but were separate in theory and in time and space (1894 [1981], pp. 351-2). However, he did think that aggregate profits preceded aggregate investment causally.

Nevertheless, the true lesson of the revolution in economic thought in the 1930s was not about “overproduction” or even over-capacity. It was that production adjusts — via price changes, inventory management, market-testing and on-demand production etc — to the prior cause of effective demand or spending (and, therefore, to its prior causes). When effective demand drops, production follows, and recessions and depressions ensue. It is of utmost importance that we do not answer tangential questions in this respect. Of course, production seems primary, in the sense that it accounts for employment and the distribution of labour across the economy. Of course, realisation can seem to be primary, in the sense that unrealised profits are not really profits at all. Yet both are subordinate to effective demand, as far as we are answering the macroeconomic question. Crudely, what changes in response to what?

Detaching profits from their causal dependence on investment spending obfuscates the arithmetical imperative contained in the earlier expression for the trend in the profit rate, namely:

To illuminate the point, consider the following three stylised figures that try to capture the kinds of ebbs and flows of investment, accumulation and profits observable in real economies (see Appendix). The figures apply the key equations and illustrative numbers above. They demonstrate that sufficiently strong investment spending (and capitalists’ consumption) lifts the mass of profits and can lift the rate of profit. If investment spending is such that its rate of growth exceeds the rate of accumulation, an increase in the rate of profit must occur by necessity. These conclusions encapsulate the second necessary consequence of Kalecki’s insight.24

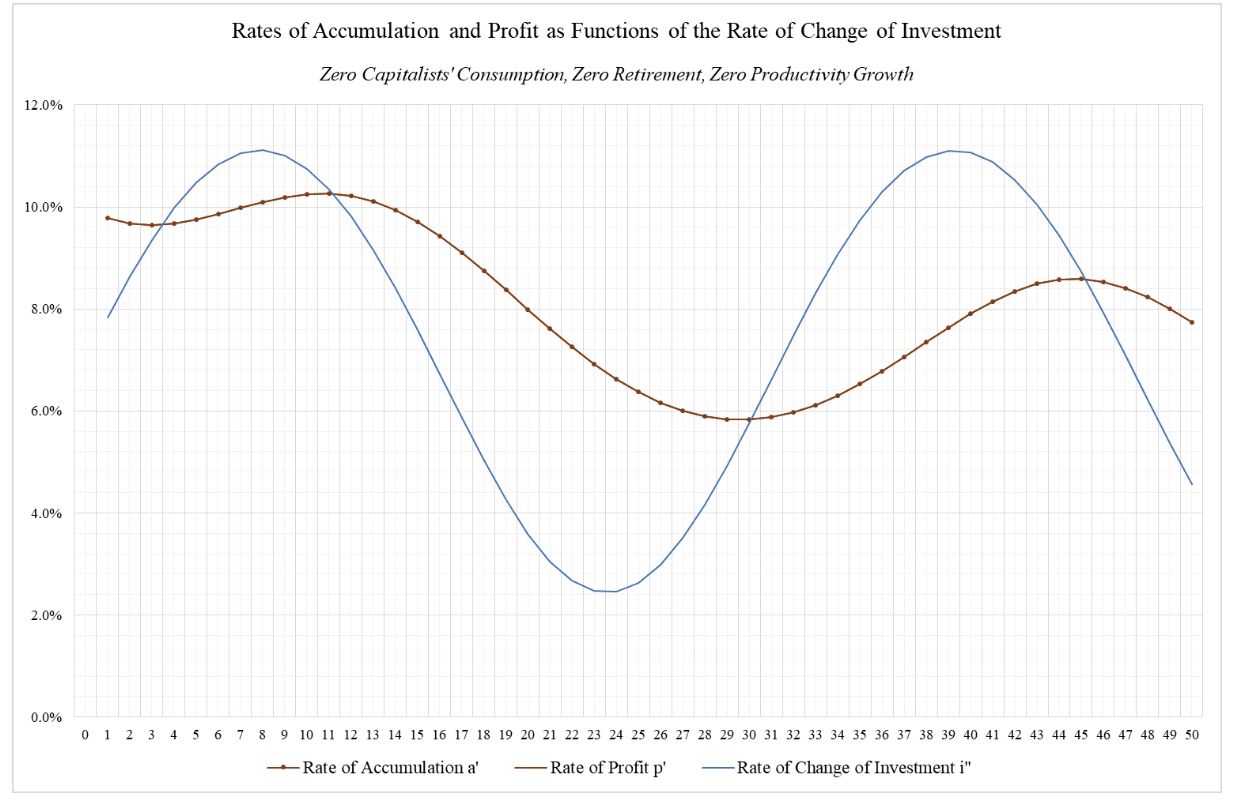

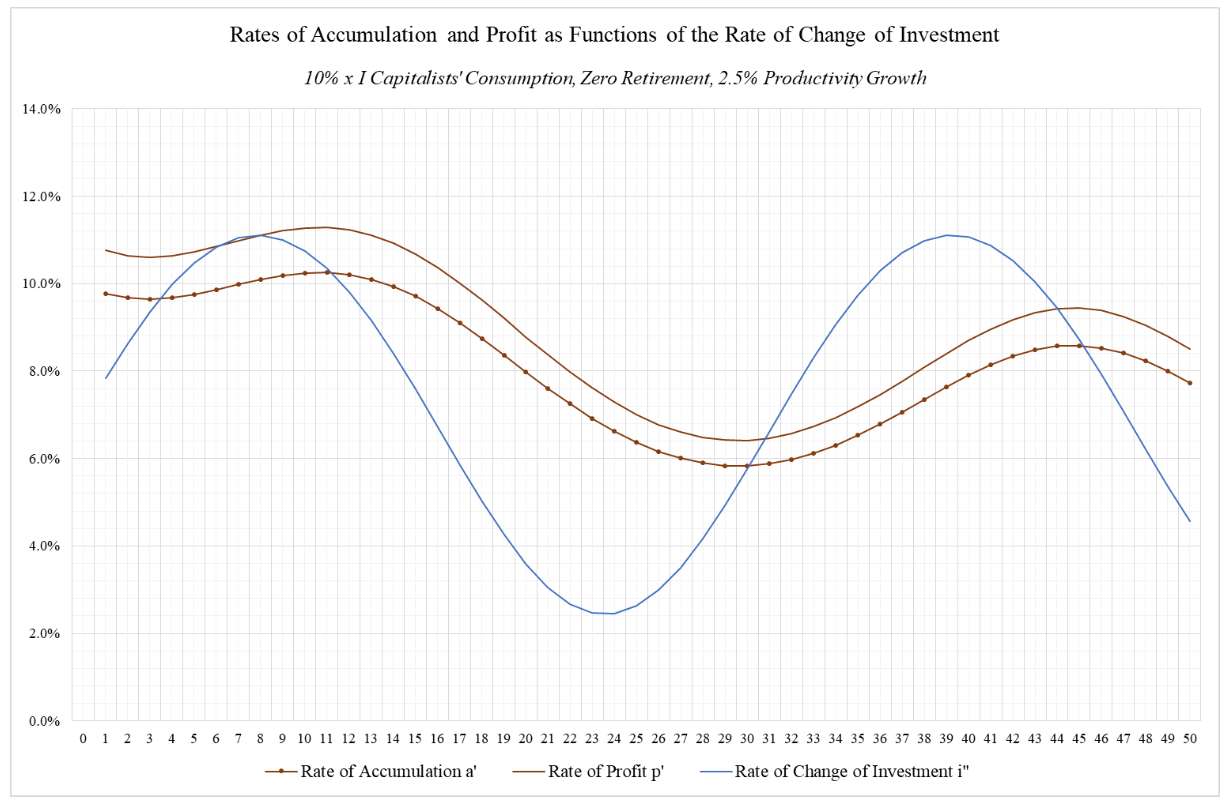

Figure 1 represents the “zero case”. Capitalists “live on air”, the capital stock lives on indefatigably and productivity growth is absent. It is useful insofar as it illustrates two important things. The first is that the rate of accumulation and the rate of profit are identical in this scenario. Both are direct and uncomplicated functions of the rate of change in investment. To be precise, all are direct, uncomplicated functions of the raw numbers for investment spending in the simple table that sits behind the figure. Investment spending is causal. The second is that the figure illustrates without clutter the essential conclusion that the rate of change of investment intersects the rate of accumulation at its lowest and highest points. As it passes through the lowest points on its way up, it drags the rate of accumulation (and the rate of profit here) up with it. As it passes through the highest points on the way down, it drags the rate of accumulation down with it. In short, relatively stronger rates of investment increase the rates of accumulation and profit and vice versa.

Figure 2 is probably closest to Marx’s case, since he does not (in fact, cannot) deal with annual rates of retirement because the regrettable one-year assumption forces the whole stock to retire (depreciate, turn over) in one year. He does consider capitalists’ consumption, however, and its effect here is to separate the rate of profit from the rate of accumulation and shift it upwards by 10% of its rate in Figure 1. The rate of accumulation remains unaffected by productivity-induced devaluation of 2.5% per period, as this affects both its numerator δC = I and denominator C in equal proportion; that is, a revaluation of 0.975% per period. Again, the critical conclusion is evident. As it passes through the lowest points of the rate of accumulation on its way up, the rate of change of investment drags the rate of accumulation up with it and vice versa. The rate of profit follows a corresponding path, peaking when the rate of investment intersects the rate of accumulation at its highest and vice versa. Note the obvious relationship between the rates of accumulation and profit: increasing rates of accumulation correspond to increasing rates of profit and decreasing rates of accumulation correspond to decreasing rates of profit.

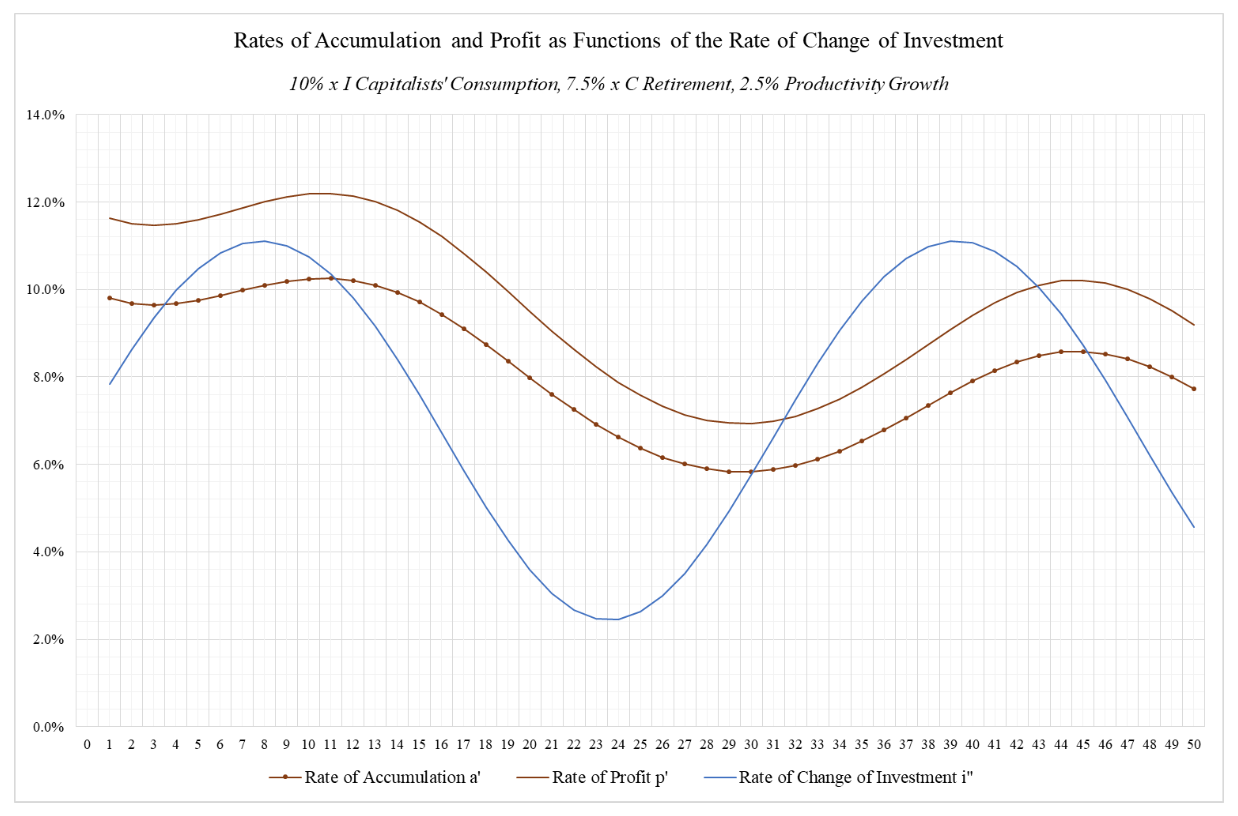

Figure 3 introduces retirement. This is a necessary corollary of chapter 4 and other additions by Engels to the Volume III that tried to clarify matters, even if not to expunge the single-turnover one-year expository device.25 Because it reduces the value of the capital stock by 7.5% per period, it shifts up the rate of profit such that it sits above the rate of accumulation by about 19% of its rate. This is the number in the earlier numerical illustration. The figure exhibits the same relationships between peaks, troughs, contours and offsetting productivity effects as did Figures 1 and 2. Again, critically for the present task, increasing rates of accumulation correspond to increasing rates of profit and decreasing rates of accumulation correspond to decreasing rates of profit.

Conclusions

This brief assessment, on its own terms, of Marx’s “Law of the Tendential Fall in the Rate of Profit” has reached unambiguous conclusions. The profit rate will not tend to fall in consequence of what Marx called accelerating accumulation. Rather, periods of investment growth that increase the rate of accumulation cause the rate of profit to increase. Those that dampen the rate of accumulation cause the profit rate to decline. These conclusions are contrary to the essence of Marx’s theory and the fate of capitalism that — despite all manner of qualifications and caveats we might try to make — he evidently extrapolated from it.

What other conclusions might we come to? One, surely, is that our attention should focus on the determinants — the real causes — of capitalist investment spending. It determines the trends in accumulation and is the main contributor to profitability and the rate of profit. The rate of profit, therefore, while remaining an important indicator, must lose much of the singular causal force often attributed to it. The rate of profit is a symptom and, perhaps, a secondary but not first-order cause. It is hardly a revelation then that Kalecki thought that the “theory of investment decisions” constituted “the central problem of the political economy of capitalism” and was “the central pièce de résistance of economics” (1971, pp. 148, 165). Those familiar with Kalecki might find the repetition of this conclusion somewhat tedious. Maybe, but that does not make it any less relevant.

A revised perspective might also help those of us who maintain an understandable attachment to Marx to grapple with genuinely challenging problems. For example, instead of trying to perform feats of imagination with ever-increasing masses of profit, footloose because of a declining profit rate, we should better be served by analysing the what, why and where of corporate investment spending — the “driving force” of economic activity. In grappling with such questions, the role of finance capital and credit come to the fore, because these actually permit capital to spend what it does, and — with a little help (or not) from its friends26 — to determine the level of profits, the profit rate and much more besides.

Appendix

Chart A1

Chart A2

References

Dobb, Maurice 1973, Theories of Value and Distribution since Adam Smith: Ideology and Economic Theory, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Doughney, James 2025, ‘Surplus Profits, Capital Exports and Imperialism: An Interrogation of Commonly Held Beliefs and Assumptions’, LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal, 9 February. https://links.org.au/surplus-profits-capital-exports-and-imperialism-interrogation-commonly-held-beliefs-and-assumptions

____ 2016, ‘Problems in Marx’s Theory of the Declining Profit Rate’, in Courvisanos, Jerry, James Doughney and Alex Millmow eds., Reclaiming Pluralism: Role of History of Economic Thought in Heterodoxy—Essays in Honour of John E. King, London, Routledge.

Eatwell, J., M. Milgate and P. Newman eds. 1987, The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, London, Macmillan.

EC, IMF, OECD, UN and World Bank 2009, System of National Accounts 2008 (SNA 2008), European Commission, International Monetary Fund, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, United Nations and World Bank, New York.

Glyn, Andrew 2006, Capitalism Unleashed: Finance, Globalization and Welfare, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

____ 1987, ‘Marxian Economics’, in The New Palgrave: Marxian Economics, pp. 274-85, from Eatwell, J., M. Milgate and P. Newman eds. 1987, The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, London, Macmillan.

Harcourt, Geoffrey C. 1972, Some Cambridge Controversies in the Theory of Capital, Cambridge UK, Cambridge University Press.

Harvey, David 2021. ‘Rate and Mass: Perspectives from the Grundrisse’, New Left Review 130, Jul-Aug 2021.

____ 2004, ‘The “New” Imperialism: Accumulation by Dispossession’, Socialist Register 40, pp. 63-87.

International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) 2018, Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting, London, IFRS Foundation, at https://www.ifrs.org/groups/international-accounting-standards-board/.

Kalecki, Michał 1969 (1954), Theory of Economic Dynamics: An Essay on Cyclical and Long-Run Changes in Capitalist Economy, New York, Augustus M. Kelley.

____ 1971a, Selected Essays on the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy: 1933-1970, Cambridge UK, Cambridge University Press.

____ 1942 (1954), ‘The Determinants of Profits’, in Kalecki 1971a.

____ 1967, ‘The Problem of Effective Demand with Tugan-Baranovski and Rosa Luxemburg’, in Kalecki 1971a.

____ 1971b, ‘Class Struggle and Distribution of National Income’, in Kalecki 1971a.

____ 1968b, ‘The Marxian Equations of Reproduction and Modern Economics’, background paper, International Social Science Council and the International Council for Philosophy and Humanistic Studies Symposium, UNESCO, 8-10 May, Social Science Information 6(7), pp. 73-9. Republished in J. Osiatyński ed. 1991, Collected Works of Michał Kalecki: Capitalism: Economic Dynamics, vol. 2, Oxford, Clarendon Press, pp. 459-66.

Keynes, John M. 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Macmillan, London.

King, John E. 2015, Advanced Introduction to Post Keynesian Economics, Cheltenham, UK, Edward Elgar.

Kregel, Jan A. 1976, Theory of Capital, London, Macmillan.

Lapavitsas, Costas and the EReNSEP Writing Collective 2023, The State of Capitalism: Economy, Society and Hegemony, London, Verso.

Mandel, Ernest 1975, Late Capitalism, trans. Joris De Bres, London, New Left Books.

Marx, Karl 1867 (1976), Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 1, trans. B. Fowkes, London, Penguin/New Left Review.

____ 1885 (1978), Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 2. F. Engels ed., trans. D. Fernbach, London, Penguin/New Left Review.

____ 1894 (1981), Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 3. F. Engels ed., trans. B. Fowkes, London, Penguin/New Left Review.

____ 1857-8 (1973), Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy (Rough Draft), trans. M. Nicolaus, London, Penguin/New Left Review.

____ 1859 (1970), A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, trans. S.W. Ryazanskaya, Moscow, Progress Publishers.

____ 1861-3, Theories of Surplus-Value, vols. TSV 1 (1963), TSV 2 (1968), TSV 3 (1971), Moscow, Progress Publishers.

Marx, Karl and Frederick Engels, 1844–95 (1975), Selected Correspondence, third edition, Marx to Engels, 11 July 1868, Moscow, Progress Publishers.

OECD (2009), Measuring Capital - OECD Manual 2009: Second edition, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264068476-en .

Robinson, Joan 1965, ‘Pierro Sraffa and the Rate of Exploitation’, New Left Review 31, May–June 1965, pp. 28-34.

Steindl, Josef 1952 (1976), Maturity and Stagnation in American Capitalism, Oxford UK, Blackwell. Republished, New York, Monthly Review Press, 1976.

- 1

Doughney, James (2025), ‘Surplus Profits, Capital Exports and Imperialism: An Interrogation of Commonly Held Beliefs and Assumptions’, LINKS, 9 February. https://links.org.au/surplus-profits-capital-exports-and-imperialism-interrogation-commonly-held-beliefs-and-assumptions Marx used the ‘surplus profits/capital’ terms infrequently and not always with the same meaning or according to subsequent usage. That is a subject for another time.

- 2

See Mandel (1975) Late Capitalism and Harvey, inter alia (2021), ‘Rate and Mass: Perspectives from the Grundrisse’, New Left Review 130.

- 3

One of the most memorable passages of the first volume of Capital (1867 [1976], p. 742) is: ‘Accumulate, accumulate! That is Moses and the prophets! Therefore…reconvert the greatest possible portion of surplus-value or surplus product into capital! Accumulation for the sake of accumulation, production for the sake of production...’ See also Capital, volume 3 (1894 [1981], pp. 351-2, p. 361).

- 4

Discussing with Nate Silver on a Substack video the economic effects of AI, Paul Krugman noted that “what Google is doing is spending vast sums on what are basically defensive investments. They’re spending to defend…[not to] enable them to establish a profitable monopoly position. They have a profitable monopoly position. What they’re doing is spending a lot of money to make sure that somebody — AI based — doesn’t come along and take it away from them.” (28 February 2025)

- 5

Controversies in such questions might have prompted Dante to create for participants their very own 10th Circle of Hell. For those brave enough to peek into this abyss, see especially Geoffrey Harcourt (1972), Some Cambridge Controversies in the Theory of Capital; see also the shorter Theory of Capital by Jan Kregel (1976) and the OECD’s much longer (2009) Measuring Capital - OECD Manual 2009. For those seeking logical reasons to avert their gaze and scamper quickly away, see Keynes (1936, chapters 2 and 4).

- 6

See for example Kalecki (1968), “The Marxian Equations of Reproduction and Modern Economics”, UNESCO, 1968, Social Science Information 6(7), pp. 73-9 Jerzy Osiatyński has republished this short work in the Collected Works of Michał Kalecki: Capitalism: Economic Dynamics, Volume 2 (1991, pp. 459-466, esp. p. 461). For an introduction to Kalecki’s thought, see John King (2015).

- 7

See for example Glyn (1987, pp. 279-83).

- 8

Karl Marx and Engels, Friedrich, Selected Correspondence 1844-95, Moscow 1975, p. 194, 11 July 1868; original emphasis. See also Marx, Grundrisse (1858-59 [1973], e.g. pp. 749-50, 763; Maurice Dobb Theories of Value and Distribution since Adam Smith: Ideology and Economic Theory (1977, pp. 157-8).

- 9

By writing and inserting the third volume’s chapter 4, Engels, as editor, mercifully clarified flow versus stock and annual versus turnover-period complications in Marx’s exposition. In doing so, he also effectively, if silently, provided readers with the tools needed to nullify annoying problems caused by Marx’s “single-turnover one-year assumption” expository device. This device allowed that the entire stock of each of the components of capital advanced (or accumulated) would turn over or be reproduced/replaced in a single year. See James Doughney (2016), “Problems in Marx’s Theory of the Declining Profit Rate”, which offers a rather more ponderous account than the one given here. An example of the lamentable tangles the one-year assumption is still causing can be found in a recent book by Costas Lapavitsas and the EReNSEP Writing Collective (2023, pp. 53-5). Alas, almost all Marxian arguments for and against the law/tendency have treated the content of chapter 4 and other additions by Engels in Wittgensteinian (Tractatus, 7) fashion: “What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence”. As did Marx, who knew quite well that his formulations of the profit rate required better articulation in annual-flow to stock form (e.g. Capital, vol. 3. 1894 [1981], e.g. pp. 243, 250, 478), exponents of such arguments perhaps thought/think that the single-turnover one-year “abstraction” permits conclusions having general validity. It does not. To be clear, the one-year assumption is: 1) absurdly unrealistic; and 2), like the proverbial raincoat full of holes, useless right when readers need clarity that capital is a stock not a flow. Moreover, 3) turnover periods within a year are obstacles to understanding annual productivity growth, a question of first importance. Therefore, 4) the assumption does not work, even as an expository device. Whether earlier political economists, or even those contemporary with Marx, used similar approaches is irrelevant. In order to make any sense at all of the declining-profit-rate controversy, one must abandon the single-turnover one-year assumption and any attempt to make a case using it. To take licence with both Dante (Inferno, Canto III) and Shakespeare (King Lear, Act III, Scene IV, ll. 17-22): abandon the one-year assumption all ye who enter here; shun it, for that way madness lies.

- 10

See especially Marx, Capital, vol. 2 (1885 [1978], p. 471 ff.).

- 11

Also, with Marx at this stage of his exposition, we assume no government and overseas sector. For a more realistic account, see the section Identities, causality and definitions in my “Surplus Profits, Capital Exports and Imperialism: An Interrogation of Commonly Held Beliefs and Assumptions”, LINKS, 9 February. https://links.org.au/surplus-profits-capital-exports-and-imperialism-interrogation-commonly-held-beliefs-and-assumptions

- 12

Marx, Capital, vol. 3 (1894 [1981], pp. 119, 205-9, 522), Theories of Surplus Value vol. 2 (1861-3 [1968], pp. 416, 473-4). NB. Revaluation is not the same as depreciation, which is the annual allocation or apportionment of the revalued purchase price of capital stock assets over their useful life. The notion of useful life accommodates the folk understanding of depreciation, namely wear and tear and technical obsolescence. Flows of annual depreciation costs reduce gross profits to net profits, while the deduction of their accumulation as stocks of depreciation provisions reduces the gross capital stock to the net stock. Gross and net profit rates correspond to these distinctions. I use the gross concept in this contribution and, therefore, must include retirement.

- 13

Marx, Capital, vol. 3 (1894 [1981], p. 363).

- 14

Michał Kalecki, ‘The Determinants of Profits’ [(1942) 1954], reproduced in Selected Essays on the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy: 1933–1970 (1971a, pp. 78-9).

- 15

According to King (2015, p. 11), “this leads [Kalecki] to the famous aphorism (which accurately reflects his views, but which no one has been able to find in his published work) that ‘workers spend what they get; capitalists get what they spend’.” Joan Robinson made the same essential point in New Left Review (May-June 1965, p. 32): “The total net profit of an economy, for, say, a year, (assuming there government budget to be balanced) is equal to the net investment of that year plus the excess of sales of consumption goods over the wage and salary bill.”

- 16

Marx furnishes an example in which the capitalist consumes 20% of profits “for his private requirements or pleasures … as man of the world (sic)”, Capital, vol. 2 (1885 [1978], pp. 198-9; see also pp. 586-8). I shall use a different guess of 10% in the illustrations to follow. The average age of the Australian fixed capital stock is about 13 years, an age that has increased only marginally (a growth rate of 0.15% p.a. on average) since 1960. That is, about 7.5% of the stock retires on average each year, a figure I use in the following illustrations.

- 17

Wherein the initial p′ itself is just a function of investment I and accumulated investment C, as mediated by the approximate constant representing the combined effects of capitalists’ consumption and capital stock retirement (and, with a caveat that will presently become apparent, devaluation). The δ symbol below simply means change in.

- 18

Marx’s “reproduction schemes” in Capital, vol. 2, (1885 [1978], part 3; see also vol. 3, 1894 [1981], chapter 49) are the locus. See Kalecki (1968) and “The Problem of Effective Demand with Tugan-Baranovski and Rosa Luxemburg” (1967) and “Class Struggle and the Distribution of National Income” (1971b) in Selected Essays, (1971a, pp. 146-64). We should note in passing that the reproduction schemes founder inter alia on the stock-flow distinction. The output formula c+v+s makes sense if c stands only for annual fixed capital consumption (depreciation), in which case s is net surplus value and c+s is gross surplus value. If, as Marx does, “we abstract … from the fixed part of constant capital” and treat c as being “the portion of constant capital consumed in production” and, by production, replaced, then his values for v and s will be in error (e.g. vol. 3, 1894 [1981], pp. 976-7). The reason, clearly enough in terms of 20th century national income accounting, is that the value of c must decompose ultimately into contributions to aggregates of v and s. Marx’s criticism of “the absurd dogma that has pervaded all political economy since Adam Smith, to the effect that the value of all commodities can be ultimately broken down into wages, profit and rent” (Capital, vol. 3, 1894 [1981], p. 980) is obviously misplaced.

- 19

Marx, Capital, vol. 3 (1894 [1981], p. 355).

- 20

For example: “The value of labour-power remains just as independently determined as that of any means of production … by the amount of labour needed to reproduce it; the fact that this amount of labour is determined by the value of the means of subsistence needed by the worker, and is thus the labour needed for the reproduction of these means of subsistence.” (Marx, Capital, vol. 2, (1885 [1978], p. 458) As for the capital stock, its “value depends not on the labour-time that it cost originally, but on the labour-time with which it can be reproduced, and this is continuously diminishing as the productivity of labour grows” (Theories of Surplus Value vol. 2, 1861-3 [1968], p. 416, see also pp. 473-4). “Fluctuations in the rate of profit that are independent of changes in either the capital’s organic components or its absolute magnitude are possible only if the value of the capital advanced, whatever might be the form — fixed or circulating — in which it exists, rises or falls as a result of an increase or decrease in the labour-time necessary for its reproduction, an increase or decrease that is independent of the capital already in existence. The value of any commodity — and thus also of the commodities which capital consists of — is determined not by the necessary labour-time that it itself contains, but by the socially necessary labour-time required for its reproduction. This reproduction may differ from the conditions of its original production by taking place under easier or more difficult circumstances. If the changed circumstances mean that twice as much time, or alternatively only half as much, is required for the same physical capital to be reproduced, then given an unchanged value of money, this capital, if it was previously worth £100, would now be worth £200, or alternatively £50. If this increase or decrease in value affects all components of the capital equally, the profit is also expressed accordingly in twice or only half the monetary sum.” (Capital, vol. 3, (1894 [1981], p. 237). See also, inter alia, Capital, vol. 3, (1894 [1981], pp. 205-9, 522), Doughney (2016, pp. 127-8).

- 21

Of course, crises can see large chunks of the capital stock laid waste by bankruptcy, asset-stripping, takeovers and so on. In this case, as long as capitalists keep spending, the profit rate will jump correspondingly. However, forcible devaluation was not what Marx had principally in mind when articulating this counter-tendency (1894 [1981], pp. 342-3). Rather, it was that the ongoing increases in labour productivity caused by capital accumulation would cheapen the elements of constant capital, the output of Department I. A credible argument concerning revaluation of capitalists’ consumption is that of opportunity cost; that it should be valued and revalued in terms of investment spending forgone. The irony of the extravagant treatment I have given “(de)(re)valuation” here should not be lost on readers. If I have erred, the only consequence should be to add weight to the logical burden Marx’s tendency must bear. That is, it must carry a counter-tendency that increases the profit rate. As I noted earlier, capital-stock measurement and its relationship to profitability are vastly more complex subjects than could be covered here, both conceptually and empirically. See the Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting issued by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB 2018); OECD (2009), Measuring Capital-OECD Manual 2009; SNA 2008, esp. p. 11 on the increased use of IASB standards in national accounting. See also Marx, Capital, vol. 3 (1894 [1981], pp. 357-9, 361, 364-8), Grundrisse (1857-8 [1973], pp. 749-50).

- 22

See also Marx, Capital, vol. 3 (1894 [1981], pp. 357-9, 361, 364-8), Grundrisse (1857-8 [1973], pp. 749-50).

- 23

Named for French laissez faire economist Jean-Baptiste Say (1767-1832). See Marx, Theories of Surplus Value vol. 2 (1861-3 [1968], pp. 423, 493), Grundrisse (1857-8 [1973], p. 411).

- 24

See also Josef Steindl (1952, pp. 240-3).

- 25

See e.g. Capital, vol. 3 (1894 [1981], pp. 94, 142, 167-8, 334).

- 26

My “Surplus Profits, Capital Exports and Imperialism: An Interrogation of Commonly Held Beliefs and Assumptions”, LINKS, 9 February, sets out a framework in which “excess spending” by other sectors — households, general government and the rest of the world — can reinforce investment spending and bolster profits and the rate of profit. https://links.org.au/surplus-profits-capital-exports-and-imperialism-interrogation-commonly-held-beliefs-and-assumptions As its task has been to assess the logic of Marx’s theory in its own terms, this contribution did not consider the obviously crucial roles other sectors play, though capitalists’ consumption has played an analogous role here. Andrew Glyn (2006, pp. 52-4) calls attention to the increasingly “active” role of the household sector, while continuing to emphasise that “Capital accumulation is the fundamental driving force of the economy. Increases in investment are usually the most dynamic element in aggregate demand expansions, particularly on a world scale” (2006, p. 86).