Was Marx wrong about the declining rate of profit?

James Doughney’s attempted refutation of Karl Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall is thoughtful and thorough. Doughney applies Michał Kalecki’s critique of Marx, paradoxically developed during the Great Depression of the 1930s — the midnight of the century — to argue there is no such law. As the world enters a new phase of de-globalisation, it is a good time to return to the fundamentals of the theory.

Doughney summarises Marx’s estimate of the profit rate as:

Let P be the annual flow of social or total surplus value or profit (surplus labour or the labour time not paid in wages) and W the annual flow of value obtained by workers (social necessary labour, the time paid for in wages and consumed to sustain working families). The total annual value added Y is the sum of W and P (necessary plus surplus labour). The average social rate of profit, on the other hand, is the ratio of the annual flow of surplus value or profits P divided by the accumulated value of labour tied up in the stock of capital C advanced for production. This stock principally comprises fixed capital, with inventories of raw materials and cash working capital representing a diminishing proportion.

The contrast between flows and stocks (circulating capital versus fixed capital) blurs the distinction between variable capital (living labour) and constant capital (dead labour). The tendency of the rate of profit to fall does not rest on the ratio between flows and stocks, but between living and constant capital. Doughney’s description here reflects the requirements of Kalecki’s system.

Doughney refers to two countervailing tendencies offsetting the tendency for profits rate to fall:

The first counter-tendency was an increase in the rate of exploitation, in effect the ratio of social surplus value or profits P to wages W. The second was the constant devaluation of the stock of fixed capital C.

There are other offsetting factors — changes to the rate of turnover, the incorporation of new populations into the capitalist system, the extension of the market, and so on — but let us concentrate on these two very fundamental points.

Marx explained there are limits to the increase in surplus value (the ability of increases in the rate of exploitation) to offset the increase in capital accumulation, as labour is not a produced commodity. This contrasts with the unlimited accumulation of constant capital both fixed (machinery) and circulating (raw materials). There are absolute and cultural limits to the expansion of the labour force: the size of the world population, the number of free workers, etc. There are also only 24 hours in the day and workers have culturally determined expectations about the intensity of exploitation, average wage rate, etc.

Over time, therefore, the necessity for capitalists to accumulate capital, the precondition for their very existence, means there will be a tendency for living labour to be replaced by dead labour or constant capital within the labour process. Living labour is squeezed out of production, replaced by machinery and a rising proportion of raw materials. The larger machines process a larger quantity of raw materials. As living labour is the source of all profits (surplus value is unpaid labour, as only workers can be paid so only workers can be unpaid) so there will be a tendency for the rate of profit to fall.

This brings us to the second offsetting factor, the ability of productivity to offset the increase in constant capital through cheapening the means of production by raising productivity. Marx examines this in Capital Volume III, Chapter V “Economy in the Employment of Constant Capital”. Notoriously, the Okishio theorem posited that if prices of production (values modified by the redistribution of profits through competition) were higher than values, and new accumulation reduced costs by raising productivity, then the rate of profit (the difference between costs and price) must rise. True, on his assumptions, but not true. Okishio’s mistake was to assume prices of production must be higher than values, when in fact they may be higher or lower than them (that is, value is redistributed in competition not created by it). He was also mistaken to assume productivity must necessarily rise faster than the increase in the physical scale of production, when it need not do so.

Kaleki’s theorem (albeit developed earlier) nonetheless develops similar themes. The problem is how can surplus arise? Not in circulation, which merely redistributes values, and apparently not in production where competition reduces values to costs. Capitalist trade and production are predicated on fair trade, the exchange of equivalents. Even where trade is unfair, this merely redistributes value but does not create it. For Marx, the value of output is necessarily identical (at least in aggregate) to the value of input, but there is nonetheless surplus value, or profit, which is indeed the very purpose of capitalist production. But how? Although the amount or cost of social labour as inputs equals the amount or cost of social labour as outputs, some of that labour is unpaid; it is a cost to the workers who expend it, but not to the capitalists who pay them. This surplus value is the source of all profit. As every exchange is an exchange of property between people, and value is a measure of the distribution of products between people and only people may own property, so only people may change the amount, production and circulation (distribution) of value. But, according to Doughney, for Kalecki capitalists create profit “it is, therefore, their investment and consumption decisions which determine profits, and not vice versa.” Doughney continues:

That is, the causality runs from spending by capitalists on Department I’s output plus their own consumption of part of Department II’s output to their profits P. In a nutshell, capitalists get what they spend.

Department I is means of production and Department II is means of consumption. All new value-added resolves into wages or surplus value, so revenue not paid to workers is necessarily surplus value, which resolves into capitalist consumption or investment — it cannot be anything else. For Kalecki, capitalist spending creates profits — “capitalists get what they spend.” Surplus value therefore originates from capitalist demand, not capitalist demand from surplus value. Capitalist consumption of luxury scrambled egg, smoked salmon and caviar creates the luxury scrambled egg, smoked salmon and caviar; they eat it before it is put on the plate. The causality is the wrong way round. The amount of capitalist spending does not determine the amount of profit, the amount of profit determines the amount of capitalist spending. Capitalists have their profits before they spend them, not after.

Far from being the devastating critique Doughney proclaims, this is the disinterment of the Reverend Thomas Malthus who proposed that the purpose of the class of unproductive parasitic wastrels of late Georgian England was to create capitalist profits by consuming them — the inversion of the actual process. Doughney continues with Kalecki’s critique of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall:

The profit rate will rise if the rate of change of investment i″ is greater than the rate of accumulation a′, and vice versa. Another way of saying this is that investment is growing proportionately by more than is the stock of capital. In the limiting case, in which capitalists do not consume and none of the capital stock retires, the rate of profit and the rate of accumulation will be equivalent.

Capitalist spending on consumption and investment produces profit, but only capitalist investment produces rising profits. Provided the rate of investment (spending on circulating capital) is higher than spending on fixed capital then the rate of profit will rise. But circulating constant capital, essentially raw materials, no more has the ability to create value than fixed capital does. The value of circulating constant capital is merely reproduced in the product. Only circulating variable capital (wage labour) has the ability to create more value than it itself costs, but this distinction is not mentioned here. Kalecki conflates variable capital with circulating capital, effectively returning to Adam Smith. This is in any respect largely beside the point for Kalecki’s critique of the law of falling profits.

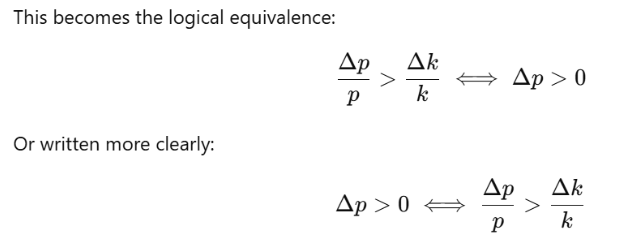

Kalecki’s central argument (pace Okishio) is that as rising productivity cheapens the cost of constant capital (fixed capital and circulating, that is raw materials), technological advance means the increase in the amount of fixed capital is always more than offset by the fall in its unit cost. Doughney explains “in Kaleckian terms, the relative value of this year’s required investment spending, and the profits consequent upon it, should be reckoned to have fallen with the cheapening of constant capital”. Expressed in mathematical proportions (rates of change or growth), let us assume:

The value of physical capital will rise if and only if the increase in the proportion of physical capital of the consumers of fixed capital is larger than the increase in the proportion of the productivity of the suppliers of fixed capital.

For Kalecki, the increase in the mass of fixed capital is never greater than the increase in productivity necessary to offset it. His problem is that there is no necessary relation between the increase in the physical mass of capital and the rate of productivity of the producers of that capital. The capitalist consumer of means of production buys their fixed and circulating capital from other capitalist suppliers of means of production separate from them. The reproduction costs of the capitalist consuming fixed capital are determined by the market in which they produce and sell their product — but the value (or price) they pay for that means production they use are determined by the different market in which the suppliers of fixed capital produce and sell their product.

As the increase in the rate of accumulation of the consumers of fixed capital is independent from the change in productivity of the suppliers of means of production, so the relation between the rate of increase in the mass of fixed capital and the rate of increase of productivity are indeterminate; they may be higher, lower or the same. The amount of fixed or circulating constant capital required for the reproduction of the original capitalist’s product is unrelated to the change of the productivity for the different capitalists who supply that fixed or circulating constant capital.

However, capitalists must of necessity accumulate fixed capital to exist, irrespective of the change of productivity. They would prefer the machine or raw materials to be cheaper, but they must buy them nonetheless. Hence, ultimately the necessity to accumulate to reproduce the very conditions of their existence, and so to increase the mass of fixed capital is higher than, and occurs independently of, the technical innovation to offset it. Therefore, the increase of the mass of fixed capital and raw materials will be greater than the increase in productivity necessary to offset it.

Marx’s general point holds irrespective, as labour is not a manufactured commodity, so the expansion of surplus value is limited relative to the accumulation of constant capital, which is unlimited. Therefore, there will necessarily be a tendency over time for labour to be displaced by constant capital, for the organic composition of capital to increase, and for the rate of profit to decline.

That does not mean, however, that in any given period, although their tendency is to fall, that rates of profit have fallen. They may have risen, stayed the same or fallen, depending on objective conditions. Profits rates largely rose through the period of globalisation from 1991 to roughly 2021. Globalisation followed the collapse of the centrally planned economies of the Soviet Union and Central and Eastern Europe in 1991, and the transition of China to the market completed with its entry into the World Trade Organisation in 2001. This doubled the size of the global working class that could be exploited by capital, while handing over huge quantities of means of production to the capitalists at no cost. This massively lowered the world organic composition of capital, increased the size of the world market, and reestablished the hegemony of the US as a guarantor of free trade in commodities and finance, enabling a technological revolution. The dynamism of this period is now being exhausted, with the advent of de-globalisation and a multipolar world.

Doughney uses figures for the fixed capital stock from the System of National Accounts (SNA) to develop estimates of the profit rate. These estimates show a marked fall in the rate of profit as an almost perpetual condition of capitalist accumulation. These rate of profit estimates assume that these SNA valuations represent the value or cost of the fixed capital advanced. They do not.

SNA valuations apply neo-classical theory to value the “stock” of fixed capital according to expected flows of capital services. They use the Perpetual Inventory Method (PIM) to estimate their Net Present Value (NPV). As the OECD explain in their 2009 Measuring Capital manual:

The central economic relationship that links the income and production perspectives to each other is the net present value condition: in a functioning market, the stock value of an asset is equal to the discounted stream of future benefits that the asset is expected to yield, an insight that goes at least back to Walras (1874) and Böhm-Bawerk (1891). Benefits are understood here as the income or the value of capital services generated by the asset.

As data about the future is an oxymoron these valuations are irrational, akin to the valuation of land using aggregated ground rent; they are fictional guesstimates of future profitability. A stock of future profits — profits that have not yet been produced — is an empty cupboard.

Michael J Harper in his 1999 “Estimating Capital Inputs for Productivity Measurement: An Overview of U.S. Concepts and Methods,” written on behalf of the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, explained what these capital services are:

We usually cannot obtain direct measures of the prices or quantities of capital service flows. However, one important type of data, which relates directly to this “shadow” market, is readily available: property income. Property income is defined as nominal revenues minus expenses for variable inputs (labor and purchased materials and services). In the productivity literature, property income is often identified with the total income from capital.

Capital service flows are property income (rents, profits and interest) or surplus value. They are not flows of depreciation, as understood in business accounting, the cost of capital advanced returning to the capitalist. The OECD explain:

Note also that the System of National Accounts (Chapter 6) explicitly states that “unlike depreciation as usually calculated in business accounts, consumption of fixed capital is not, at least in principle, a method of allocating the costs of past expenditures on fixed assets over subsequent accounting periods”. In other words, depreciation is a forward-looking measure that is determined by future, not past, events.

Depreciation in the SNA means the rate at which capital services (profits) fall over time. The discounted aggregate of these capital service flows forms the valuation of the fixed capital stock:

In order to determine the appropriate weights for capital aggregation, we need to consider the costs, to the investor, of furnishing each type of capital input. An important assumption is that the price of an investment good will equal the discounted value of the services it will provide in the future.

Doughney’s rate of profit formula actually divides surplus value by aggregated guesstimates of future surplus value (estimated capital services multiplied by the service life). Paradoxically, as these capital service flows (the anticipated rate of profit) diminish or depreciate over time, based on an observed tendency for the rate of services (profits) to fall, they confirm the very trend that Doughney is so eager to deny.

The misconceived use of this fictional “data” in Marxist rate of profit of estimates grossly underestimates the rate of profit, as surplus is higher than costs. An increase in surplus in the numerator will be multiplied by the service life in the denominator, so a rise in the mass of profit will be translated into a fall in the rate of profit. Hence, as the mass of profit rises, so the rate of profit using these fictional statistics falls. As is clearly demonstrated in Doughney’s graphs.

I examine these issues further in my 2022 article in Capital and Class “The US rate of profit 1964–2017 and the turnover of fixed and circulating capital” and in my 2025 book War and the World Economy.