‘A desperate situation getting more desperate’: An interview with Rashid Khalidi

First published at The Drift.

Since Hamas’s gruesome attack on October 7, we’ve watched as Israel has — with our government’s blessing and material aid — bombarded the captive residents of the Gaza Strip and displaced more than a million people. As protesters around the globe have expressed outrage at Israeli violence, a series of debates has played out on the American left: over whether mourning the deaths of 1,400 Israelis lends cover to Israel’s military brutality, or failing to voice grief is tantamount to condoning Hamas; over whether the proper historical analogy to invoke in this moment is 9/11, or the Algerian independence movement, or the campaign against apartheid in South Africa; over whether those out in the streets, or on cable news, are betraying their ignorance of history.

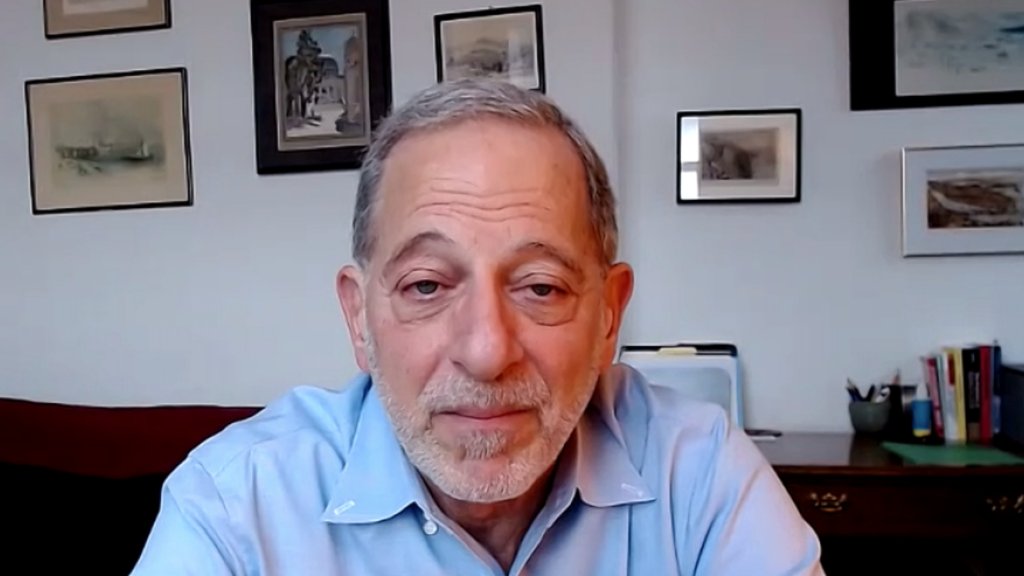

We turned to Rashid Khalidi, a scholar of modern Middle Eastern History and an editor of the Journal of Palestine Studies for over twenty years, for some perspective. Khalidi is the Edward Said Professor of Modern Arab Studies at Columbia University and the author of eight books, including, most recently, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine (2020). He also served as an advisor to Palestinian negotiators during peace talks in the 1990s. We spoke with Khalidi about the response — in the U.S., in the Middle East, and elsewhere — to the events of recent weeks, the history of the Zionist project, past peace processes, and the distinctions he wishes young activists were making now.

Recent events have been described in the mainstream discourse as unprecedented, and representative of a rupture with the past. To what extent is that the case? As you wrote in the Journal of Palestine Studies back in September, 2023 was already the bloodiest year for Palestinians in the West Bank in nearly two decades. Is what we’re seeing now an inevitable conflagration?

I don’t think anybody could have predicted what we’ve just seen in the past two weeks. I mean, the fact that the Israeli army, one of the largest in the world, with one of the best intelligence services in history, had absolutely no idea what was coming — and there will be commissions of inquiry and war-college studies of this intelligence failure well into the future — shows that nobody could have predicted it. The only people who knew were the people who launched this attack. At the same time, anybody who had any sensitivity to the details of what was going on inside the occupied territories, and inside Israel, would have been able to assume that some kind of explosion was inevitable sooner or later. Hamas is not just an operation in Gaza — Hamas is a Palestine-wide organization. They were extremely sensitive to the fact that, especially since this new government came into office, but also in the year preceding, the number of Palestinians being killed in the West Bank, the number of settler incursions, the number of attempts to organize Jewish worship in the Haram al-Sharif, around the Aqsa Mosque, were increasing. And the amount of land being stolen by settlers was also rising. Most recently, three small villages in the West Bank, largely nomadic populations, have been driven off their land.

Ethnic cleansing has been underway at a very low boil level, not high enough for the world to pay any attention. And burying the Palestine question, burying a political horizon for Palestinians, seemed to be the primary endeavor of Western countries and Israel, as well as some of Israel’s Arab allies. As far as the Israelis were concerned, this was the best of all possible worlds. We were going to have railway lines running from Mecca to Haifa; we were going to have Israeli raves in the Saudi desert; we were going to have love, friendship, peace and security arrangements forever and ever. And all of this was going to be done with the Palestinians under the boot of an Israeli occupation that would continue indefinitely. Palestinians, all of them, saw that. Not everybody reacted the way Hamas did, obviously. But everybody saw that this was a desperate situation getting more desperate, and that their interests and rights were being completely ignored by all and sundry — not just Israel or the United States or its western client-allies, but also by Arab countries.

If you watch CNN, you’ll see Israeli generals being allowed to claim, without pushback, that Israel avoids civilian deaths (or is giving Palestinians the “chance to evacuate” out of a sense of humanitarianism), immediately after scenes of apartment buildings, university campuses, and the evacuation route being blown up in Gaza. The New York Times Editorial Board likewise wrote, “What Israel is fighting to defend is a society that values human life and the rule of law,” in the same pages as news reports that demonstrate that Israel has ordered the killing of thousands of people, against international law. These mainstream accounts are confusing at face value, and profoundly alienating as referenda on the media’s ability to report on Israel honestly. How have you been interpreting the mainstream coverage of this assault?

You know, I used to write about Soviet Middle East policy, and in those days, the only sources we had were Pravda, Izvestia, Krasnaya Zvezda, and so on. I feel today like I’m back in the Cold War and The New York Pravda Times and Washington Izvestia Post are mouthpieces for the Biden administration and its locked-at-the-hip ally Israel. I find, in most of the mainstream media, essentially wall-to-wall war propaganda.

We have a memory-free, history-free, fact-free sphere, in which, for example, it goes unnoticed that a retired army chief of staff who recently joined the Israeli cabinet, a man called Gadi Eisenkot, was Chief of Operations of the Israeli Army when they flattened Lebanon. And he said at the time that he had developed what he called the “Dahiya doctrine.” The Israeli Air Force flattened the whole neighborhood of Dahiya, and he said, “We will apply disproportionate force on it and cause great damage and destruction there. From our standpoint, these are not civilian villages, they are military bases.” He also promised that “what happened in the Dahiya quarter of Beirut in 2006 will happen in every village from which Israel is fired on.” Eisenkot is now a minister. He’s one of the people planning this war. He has told you what he does: He does not not respect international humanitarian law. I wrote an article in the Journal of Palestine Studies about this. Now, would I expect the average journalist to read the Journal of Palestine Studies? Unfortunately not. The point is, even those who may know about those things are not able to do those kinds of stories. I talk to reporters all the time, and I know what kind of stories they’re asked to write by their bosses. Sometimes, occasionally, journalists push back.

We can see this happening across the government, too, where government employees, at the State Department and elsewhere, are angry at the position of the U.S. government. We see this across universities, where diktats are coming down from administrations. We see this in companies taking public positions. It’s like the United States is at war, and we must all toe the line and be in lockstep with Israel, behind which marches the president.

Tell us about the various Palestinian leadership groups (the P.A., the PLO, Hamas) and their origins. What does it mean to label Hamas as a “terrorist organization,” and equate it with ISIS, as official Israeli social media graphics have done?

The U.S. President — the highest voice in the land, not that he has much of a voice — has specifically compared Hamas to ISIS. So we’ve had “unadulterated evil.” We’ve had “worse than ISIS.” We’ve had 9/11 comparisons. This is about as high as you can go on the apocalyptic scale. This fits an Israeli playbook, whereby Hamas is described as terrorist and nothing else. It was a government in Gaza. It was a political, social, cultural, religious organization.

Palestinian politics are in particularly dire straits right now. What used to be the largest rival of Hamas, Fatah, is in decline because of its association with a corrupt, inept Palestinian Authority in Ramallah. The Palestinian Authority has basically taken over for the PLO, something that Arafat started when he moved his operation into Palestine after the 1993 Oslo Accords. Now the PLO is moribund, and Fatah is almost moribund. The P.A. has no strategy. It is committed, supposedly, to a diplomatic approach and nonviolence, but with almost no support among Palestinians, since they have seen this approach go nowhere for decades while settlements expand and Palestinians are squeezed into less and less space. Many Palestinians hate the Palestinian Authority, because it does Israel’s bidding and is propped up from the outside. This is a constant in Palestinian politics, going back to the ’30s: the interference of Arab countries and foreign powers that arrogate to themselves the right to speak for the Palestinians, or divide the Palestinians up, or weaken the Palestinians, or treat them as clients. Arab countries and other countries want to use the Palestinians or Palestinian organizations for their own aims.

The P.A. is propped up — at the same time as they kick the props out from under it — by Israel, by the United States and Europe and a number of Arab countries. Hamas is supported by regional powers: Iran, obviously, but also Turkey and Qatar, and others. The Iranian regime, the Assad regime, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt all have their own objectives, and their own national interests. Palestinians have overcome this in the past, and they have to overcome it if they’re ever going to get anywhere. But it’s not going to be easy. Where a new generation of leadership is going to come from, where a strategy that is going to move the Palestinians towards their goals is going to come from — I don’t know.

How should we situate the present dynamics in Palestine within the broader context of the region? Many U.S. pundits have speculated that Hamas was aiming to disrupt Israeli-Saudi normalization (while the label “Operation Al-Aqsa Flood” indicates, for instance, that this was a response to incursions at the Aqsa Mosque). How has the U.S.’s cultivation of Arab client states like Saudi Arabia altered the relationship of Palestinian liberation to pan-Arab politics?

You just have to read or listen to the statement made by the person who seems to have engineered this attack, Mohammed Deif, the military commander of Hamas. He said what the objectives were on the first day of this attack. He mentioned the attempts to turn the Haram al-Sharif, the area around the Aqsa Mosque, into a site of Jewish prayer. I saw this when I was in Jerusalem in March: groups of Israeli settlers, religious settlers, escorted I think by border guards and police, entering from the Magharibah gate, the Moroccan Gate, and then praying in the southeastern corner of the haram, about twenty or thirty meters away from the Aqsa mosque. Every day, they kick worshipers out after the morning prayers: Muslim worshippers, and young people, especially. They chase everybody away, and they allow these settler groups to come and pray. These groups have been growing larger and larger. During Sukkot, days before the attack it just happened that thousands of settlers came to have collective public prayers in the mosque compound.

Of course, the attack was apparently planned for two years, so the latest escalation of this process had nothing to do with it, but it was a rallying cry. So whether they really mean it or whether it’s a ploy to win over Palestinian, Arab, and Muslim public opinion, is irrelevant. Clearly, that’s one motivation. And Deif went through a list of others, such as the siege of Gaza, the creeping colonization and annexation of the West Bank, and the fact that the Israeli government operates as if the Palestine question didn’t exist. That was an indirect way of saying that normalization has been ongoing throughout the Arab world over many years, since Anwar Sadat went to Jerusalem in 1977. It has been topped recently by the flirtation between Israel and Saudi Arabia, with Israeli ministers going and praying in Saudi Arabia, and the Crown Prince saying that he was looking forward to Israeli-Saudi normalization happening at some stage. There were orgasmic Israeli responses to this.

Every ignorant pundit with no sense of history who talked about how unimportant the Palestine issue was to ordinary Arabs or to the Arab countries should never open their mouth again. Because what we have seen is demonstrations in Egypt, Jordan, Turkey, Lebanon, Morocco, Bahrain. Some of these are jackboot dictatorships, where nobody’s allowed to demonstrate. Nobody’s allowed to express themselves. And yet, public opinion across the Arab world has erupted in support of Palestinians. There have been monumental demonstrations. Yemen is a country devastated, a failed state. They have a civil war, they’ve been bombed by the Saudis and the Emiratis for years and years, and they’re out in the streets demonstrating for Palestine.

I’ve found some four hundred newspaper articles published before 1914 in a dozen Arabic newspapers, from Cairo to Damascus to Aleppo, talking about Palestine and Zionism. People in the Arab World were concerned about this 110 years ago. They were concerned about this during the Arab Revolt of ’36-’39, and they were concerned about this during the Nakba, and they’ve been concerned about it ever since. Have Arab governments represented that concern? Rarely. Never. Sometimes. But that’s not the point. These are undemocratic regimes — absolute monarchies or jackboot dictatorships, and they represent nobody and nothing except their own kleptocracies, the people who are being enriched by them, and the foreigners who keep them in power with weapons or diplomatic support.

This is not just the Arab world, or even the Muslim world. The Americans, the Europeans, the white settler colonial bubble, which produces a very large share of world GDP, and which has enormous media reach, enormous power — aircraft carriers, stock exchanges, media conglomerates — still think of themselves as the masters of the universe. They’re a tiny minority of the world’s population. India, China, Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Brazil: those are some of the world’s largest countries, and people there don’t have the same view of this at all. Here we have a sanitized worldview produced by a compliant corrupt media and the American and British governments, which have decided that support of Israel is a national interest. And then you have the world — the real world — which is on a completely different page. This deepens the gulf between the West and the rest. I think the Ukraine War started this. In most of the world, nobody looks at the Ukraine War the way that the United States and its European allies do, which is visible in the way the General Assembly has reacted to it. It’s not that people are supportive of Russia, necessarily; it’s that they don’t see it in the same hysterical, hyperbolic fashion as the United States and its closest allies and — perfectly understandably — Ukrainians and Eastern Europeans do. What’s happening now in Palestine is accentuating that, and is going to diminish the power and the standing and security of the United States and its allies. Americans who talk about human rights and democracy are going to be treated as the most rank, nauseating hypocrites going forward. Nobody believes that rhetoric in the rest of the world, with good reason.

The word “occupation” does not exist in the American lexicon where Israel is concerned. The occupation is not an “obstacle to peace” — it’s an aggressive, violent imposition, which is designed to turn Palestine into the land of Israel, as Zionist leaders have been trying to do since Theodor Herzl. So when the United States bleats about the occupation of Ukraine, and then links Hamas and Putin, as Biden attempted to do in his Oval Office address, nobody buys this stuff, except people in the Anglosphere who are either ignorant or brainwashed. But a CBS poll showed that a majority of Democrats and independents oppose military aid to Israel; most Americans are a lot more sensible than those who govern us.

Zionism is a settler-colonial project, but Israel became a state in a postcolonial era. How do you think about that history, and how it continues to inflect the current situation?

Tony Judt wrote that Israel “arrived too late” and was an anachronism. The point is that had it been launched in the eighteenth century, it might have succeeded. It would have been in keeping with the spirit of the times, which was that white Europeans had rights that nonwhite non-Europeans didn’t, and that they could arrogate to themselves any area of land and do anything they wanted with it and with the indigenous population. That was the rule of the jungle from Columbus right up to the twentieth century, really to World War I.

Zionism was never ashamed, in its early decades, of describing itself as a colonial project. It was and is a national project. It also was and is a spoiled stepchild of imperialism. Why was Herzl going to the Kaiser? Why was the first president of Israel, Chaim Weizmann, going to the British? These were not disinterested, neutral, Switzerland-like powers — these were the great imperial powers of the age, which were going to do the dirty work for the Zionist project. Were these people colonists and settlers? They called themselves colonists and settlers. The “Jewish Colonization Association” is not some antisemitic slur — it’s what this important body called itself. Of course, all of this has been airbrushed out. Saying “settler colonialism” is a terrible, terrible thing today, even when describing what’s happening in the West Bank, which is the most American-frontier-like dispossession imaginable in the 21st century.

That brings me to what the United States has just done, or tried to do. The United States government apparently was complicit with an Israeli plan to remove a part or all of the population from the Gaza Strip to Egypt, and possibly to other places. There’s no question that Antony Blinken was doing that — collaborating with Israel to remove the Palestinians in completion of the ethnic cleansing that was started in 1948.

This is a demographic war. Everybody in the Zionist movement, in Palestine, and in the Arab world, from the ’20s and ’30s onwards, understood that you replace Arabs with Jews and you get a Jewish majority; if you don’t do that, you have an Arab majority. Reducing those numbers was and is a prime Zionist objective. That the United States is lending itself to this, besides possibly being a war crime, is monstrous — absolutely immoral. Nobody who’s kicked out is ever allowed to return. Every Arab, every Palestinian knows that. Nobody driven into Egypt will ever come back to Gaza or any other part of Palestine. Most of these people, of course, have already been displaced. They’re the population of southern Palestine who were driven out in 1948 and have been penned up in the Gaza Strip for the last 75 years. Moving them again would be criminal. And our government has participated in trying to do that.

Now, for various reasons — some of them savory, and some of them unsavory — the Egyptian government has refused, backed by the Saudis and everybody else in the Arab world: “We should become complicit in your ethnic cleansing of Palestinians. Are you insane? You really want us to lose our thrones and our fortunes? You really want us to be overthrown by our own people for being agents of Israel and the United States?” I don’t think that’s what Egyptian president Abdel el-Sisi actually said to Blinken, or what the Crown Prince actually said to Blinken. They refused to even meet with Biden. These are regimes I am opposed to without exception, but I have to say, they did the right thing in refusing to meet the president. And they did the right thing by giving Blinken two well deserved slaps across the face. The Crown Prince kept him waiting for ten hours, Sisi upbraided him in a public press conference. That’s a sign of what’s changing in the region.

How should we look back on the Oslo Accords and related efforts? Has there ever been a legitimate attempt to make peace?

There have been attempts, but I would argue none of them ever really grasped the nettle. And the nettle is, how do you have a sovereign majority Jewish state in a majority Arab country. There has never been a solution — in Madrid or Washington or Oslo or Camp David — that respects the fact that this was a settler colonial process, or the fact that you now have two peoples there, one of which has all the rights and the other almost no rights. There were attempts to come closer to it, but I think you can go back to what former Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin said in the Knesset in October 1995, before he was killed for going too far even with that, which was that any Palestinian entity created through Oslo would be “less than a state.” It was always an assumption of the United States that Israel would continue to have security control over Israel and Palestine. It was always assumed that the Palestinian state would be less than sovereign, and that it would be a fragment of a fragment of historic Palestine — in other words, not even the 22 percent that was left at the end of the 1948 War, but even less than that. From the time Rabin came to power in ’92 until his assassination in ’95 and then through the rest of the so-called Oslo decade, Israel was expanding settlements at a breakneck pace, taking over more Palestinian land and making a mockery of the Oslo Accords, and was hemming in Palestinians in little Bantustans, all of which have been shut down now.

Anybody who says “oh, the Palestinians rejected a generous peace plan” is not looking at what really was happening on the ground. Israelis had other objectives, one of which was the permanent settlement of most of the occupied territories, another of which was permanent control over all of Israel-Palestine, neither of which is compatible with sovereignty, or statehood — even reduced statehood. Again, you simply have to read Rabin’s last Knesset speech to see that.

A common Zionist framing is that pro-Palestinian activism or advocacy denies the right of the State of Israel to exist and that slogans like “from the river to the sea,” are themselves genocidal. How do you read this?

There are a lot of Palestinians who don’t believe that Israel has a right to exist. There are a lot of Palestinians who don’t believe that there’s such a thing as Israeli peoplehood, which there manifestly, obviously is. Israelis are a people. A lot of Palestinians don’t realize that many settler colonial projects have created peoples. We live in a settler colonial project in the United States. Anybody who’s not part of the original indigenous population is a settler. But as Mahmood Mamdani’s book Neither Settler nor Native asks, when do the settlers become natives? It’s a thorny question politically, because even if you accept that there’s an Israeli people, and if you say peoples have the right to self-determination, this is coming on top of a process of denial of Palestinian identity and national rights, dispossession, expulsion, and ethnic cleansing. All of those things have to be understood and addressed before you’re going to be able to figure out how these two peoples come to terms.

What I’ve just said is not something you can fit into a slogan or the kind of heated propagandistic claims that you just mentioned. I personally have no problem with people seeing the Land of Israel stretching from the river to the sea or wherever else they think it may stretch. The question is, what political and other consequences flow from that? If that means absolute, exclusive rights for one people and the oppression of another people, then obviously that’s not acceptable. And the same would be true of Palestine. “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.” What does that mean? Well, if it means the Palestinians are no longer oppressed, but don’t oppress Israelis, I would hope that would not be a problem. But, again, different Palestinians have different views on this. And I think that the heightened repression and offensive actions taken by Israeli governments over many years have driven Palestinians from where they were in the Oslo period, when they were willing to accept a manifestly unjust two-state solution, as long as it ended up involving real Palestinian sovereignty and statehood, to wherever they are today.

In recent years, progressives in the U.S. have focused on the possibility of a one-state solution as opposed to a two state solution. In light of the situation now, should we be changing our tack? In a moment of complete despair, is there a reason to hope for either solution at all?

I’m pessimistic that either of these two solutions is currently possible. Israel and the United States have in practice worked feverishly ever since 1967 to ensure permanent Israeli control over the Occupied Territories, to settle them to a greater and greater degree, and to make sure that under no circumstances can an independent Palestinian state or any other non-Israeli sovereignty ever operate anywhere in the territories Israel took over in 1967. And they have done everything they can to cement over the West Bank and turn it into Israel. Everything. They tried to settle Gaza as well, but they gave up on that in 2005. The United States government pays for this and arms this process. It talks out of one side of its mouth about a two state solution, but it allows Israeli settler groups to be 501(c)(3)s and funnel hundreds of millions of tax-free dollars to the settlement project. It arms the Israelis who prevent Palestinians from doing anything about this, and enforces the occupation by giving diplomatic support and veto after veto in the Security Council to this ongoing bulldozing, absorption, annexation, and destruction of Palestine. Most of those talking about a “two state solution” don’t really mean it. They don’t mean an independent, sovereign Palestinian state on the territories occupied in 1967. They mean some simulacrum, some Potemkin state. That’s what they mean. And they’re doing everything possible to prevent even that.

So how do you get these two people to live together in one state after the blood that has been shed? And it will, I’m afraid, continue to be shed. I don’t know. I don’t think that in the short term, there’s any particular reason for optimism about any solution.

On the other hand, everybody thought, until the seventh of October, that the Arab world was moribund and didn’t give a hoot about Palestine. Things changed very, very quickly. The Israeli public is bent on revenge, out of its rage and grief and anger — in particular, over the civilian casualties, but also over the collapse of every doctrine that the Israeli military has ever promulgated about security. Clearly, the Israeli people are not secure. Clearly, everything everybody thought was wrong, not just about Hamas but also about Israeli military capabilities.

So right now, you’re not going to get a swing towards peace among Israelis. The mourning is going to go on for a very long time. And if Israelis are grieving and enraged, so are Palestinians. These are huge Palestinian civilian casualty numbers now, and we still don’t know the final tally. It’ll take a long time to get over. But that too might change in the future.

But one hopes that someone somewhere is going to begin to say that Israel’s political approach is completely bankrupt. You cannot continue to hammer the Palestinians with violence without expecting a violent response. This is not to justify anything, it’s simply to explain that if you apply that kind of pressure to an oppressed population, it will rise up in ways that may be horrible, in ways that may be politically wrong or morally wrong. If you apply intense, unceasing pressure, there are going to be explosions.

What do you make of the conversation within the American left — the elected left, the activist left, the left media? Is there history the left is missing or leaving out?

Well, that’s a hard question for me to answer because all I am directly in contact with are student activists. I think that young people are in the process of educating themselves, and they’re not yet fully educated, or politically mature in their views.

For example, an argument that I see among some student activists is that all Israelis are settlers, and therefore there are no civilians. You can’t say that if you have any respect for international humanitarian law. Israel’s being the result of a settler colonial process does not mean that every Israeli grandmother and every Israeli baby is a settler and therefore not a civilian. Technically, in some sense, we Americans are all settlers, but that does not mean that a Native American liberation movement would be justified in killing white American settler babies or white American settler grandmothers. Yes, people in the settlements in the Occupied Territories who are armed have to be seen as combatants. The ones who are unarmed are not combatants. That’s an example of the kind of distinction people have to develop.

I’ve been criticized for saying that it has been the case historically that liberation movements have not been careful in avoiding targeting civilians. In the Battle of Algiers, Zohra Drif and Djamila Bouhired put bombs in cafes and bars. They were tried and convicted and spent years in jail and were ultimately liberated. They’re national heroes in Algeria and they’re both vigorously supporting democracy against the military junta which still rules Algeria. You can talk about what the IRA did against civilians, and you can talk about what the ANC did. There’s a very significant debate around this issue to be held among people involved in national liberation. I follow the situation in Ireland closely and people are questioning those things today. They are able to do so because, since 1998, people are not killing one another at anything like the same pace, thank god. It’s hard to do in the middle of a situation like Palestinians are in right now, but activists have to think carefully about those things.

The other thing I would say to student activists is you have to understand what your political objectives are. If you believe that this is a settler colonial project, then you are in the metropole of that colony, here in the United States or in Western Europe, and national liberation movements have won not only — sometimes not primarily — by winning on the battlefield in the colony. The Vietnamese were at a stalemate with the Americans. The Algerians were actually losing on the battlefield. The IRA was almost at the end of its tether, militarily, in 1921. They won, in part, because they won over the metropole. The English finally said, we just don’t want to fight this war. We can’t fight this war. Same thing happened with the French in Algeria. It wasn’t only the fighters up in the mountains who won the war. I’m not saying that wasn’t a crucial element in the liberation of Algeria, indeed the sine qua non for it, but if the French had continued to want to kill Algerians, the war could have gone on forever. French people didn’t want to continue, because they didn’t want to take more losses. Same thing with South Africa. They did not win only in the townships; the ANC won because in the United States and Britain, they won over public opinion.

If you believe this theoretical construct — the colony and the metropole — then what activists do here in the metropole counts. You have to win people over. You can’t just show that you are the most pure or the most revolutionary or can say the most extreme things and demonstrate your revolutionary credentials. You have to be doing something toward a clear political end.