Italian elections: Heading for a Meloni far-right government?

Reposted from Anti*Capitalist Resistance, September 8, 2022.

Cantagallo is a well-known service station on the main north-south motorway on the outskirts of Bologna. We have stopped there many times. A journalist from the leading Italian newspaper, Corriere della Sera, went there on the 15 August Farragosto bank holiday. He hung around, listened and talked to people who were there. A father was there with his bored son telling him how he had one of his first meals out there when it had just opened. The son kept playing on his phone.

For southern migrants to the north like this man the service station represented his social promotion, his entry into a degree of prosperity and modernity. For many migrants their wages earned in the booming factories allowed them to buy cars and travel back south to see their families in August. The future looked bright. In the 1970s Almirante, the neo-fascist leader of the MSI (National Social Movement) stopped at Cantagallo for a bite to eat. He managed the pasta course but when the workers there noticed he was there they brought him the bill and told him to leave before the second course. Almirante left. Thanks to the mass radical upsurge of the Hot Autumn in 1969 working people had not only won better living standards but had a sense of themselves as political protagonists.

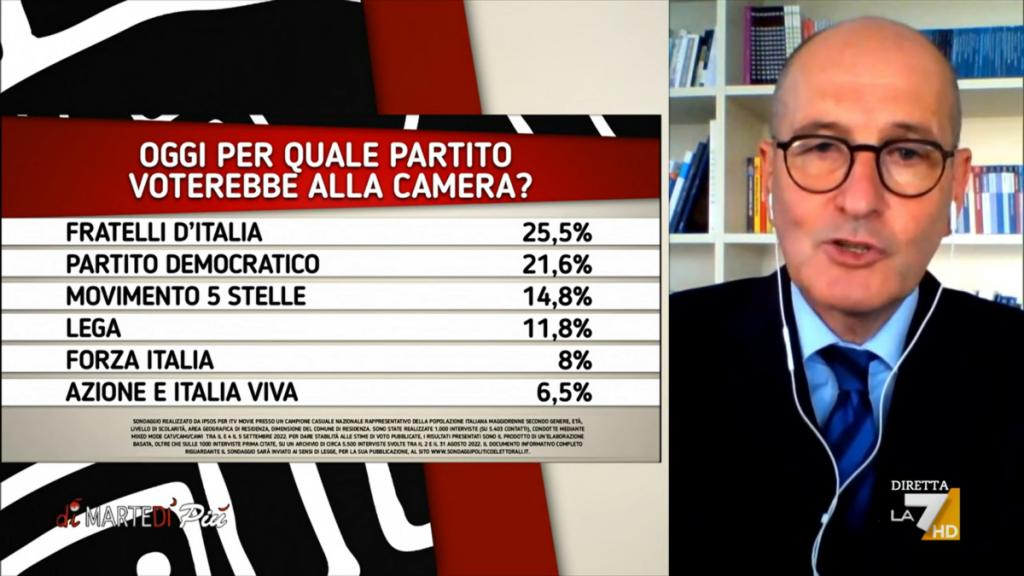

Later on, the journalist wandered down to speak to the lorry drivers who were working that day. They were eager to talk about the exhausting schedules they now had and the cut-throat, increasingly unregulated logistics sector. Comments were made about the Albanian drivers who would supposedly work for 12 hours at a stretch. Asked about their voting intentions for the 25 September general election, a significant majority said they were going to vote for Giorgia Meloni, the leader of Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy), who was the youth leader in Almirante’s party. The latest poll on September 6 credits Meloni with 25% of the vote within a 46 to 28% right wing majority which means she becomes Prime Minister. Meloni’s rise and the probable victory of a right wing coalition anchored to the hard right is mostly a consequence of the defeats and demoralisation of the workers’ movement and the political bankruptcy of what used to be its social democratic majority party, the PD (Democratic Party).

Declining political engagement

Since the last general election in 2019, there have been three governments. The first was a lash-up between the two populist parties, the Lega (League, formerly the Northern League in favour of Lombard autonomy) and the M5S (the Five Star Movement started by comedian Beppe Grillo). These parties had emerged after the collapse of the two-party Christian Democrat/Communist system in a sea of scandal and corruption in the 1990s.

The first Conte Government collapsed when the Lega leader, Salvini, made a move to have more influence but was faced down with the help of the Italian president, Matterella. The latter organised for the PD, the sworn enemy of the M5S, to join them in the second Conte government. A year or so ago this went the same way as the first one and the Euro banker, Mario Draghi was drafted in to form a national unity government. All the mainstream parties joined this….except Meloni’s FdI whose ratings went from 4% to today’s 25%.

Although polls registered majority support for Draghi the frustration and alienation of many Italians remained acute. The main policy achieved by the government was the European Union financed 200 billion euro post-Covid national recovery and resilience plan (PNRR). Not much of that money is going to maintain peoples’ living standards, mostly it is infrastructure and ‘modernising’ changes to make Italian capital more efficient and profitable.

Meloni has benefited from this reality and from a general perception that all the other parties were involved in the continual chopping and changing of alliances in order to hold on to their privileges and power. Draghi – to the clear dismay of the key capitalist establishment in Italy and Europe – threw the towel in on his government in July when Conte made a sudden ‘left’ turn in defence of the M5S’s signature citizen’s income policy and refused to fully endorse the government. So this is what led to the vote on 25 September.

The shift that the Corriere journalist eloquently indicated in his article is also about general involvement in politics. After the Second World War 9% of Italians were members of political parties. Today the figure is down to 1%. Local party branches – both left and right – were real community hubs. For example, in the town, I know well the local CP branch was a social and political meet-up point for all the left, not just CP members. The party would run summer ‘fetes’ with political/cultural discussions, music and food in the centre of town and in the periphery villages. Today the party office is a supermarket and they may be the odd regional festival. The daily CP newspaper, Unita, closed down in 2014. Parties today are fluid and liquid. The M5S operates mostly online for its discussion and voting. Members, sympathisers and voters are assimilated and participate in primary elections to decide on candidates but there are a lot less structured political debates about ideals or policies. Parties of both right and left are areas for careerists to compete for salaried positions, privileges and positions of power.

In the post-war period democracy and one of the most progressive bourgeois constitutions meant 93% of people voted. I remember how astonished I was in the 1980s to see the sheer numbers voting in all types of elections compared to Britain. Today the figure is down to 73% and falling. All the polls currently are pointing out the high level of abstention and the lack of interest in the election. I asked my niece, who is a graduate with an admin job in the private sector, who she was going to vote for and she said they were all the same and only looked out for themselves. She also saw little point in the trade unions.

How much of a threat is Meloni to democracy and the labour movement?

A lot of the commentary in the mainstream and left press here has been about the threat Meloni poses. People have noticed that the election in September coincides with the centenary of Mussolini’s march on Rome when the fascists took power. If Meloni becomes Prime Minister, should we expect new restrictive laws against free speech, assembly or union rights? Will it be a signal for an outbreak of physical attacks by fascists against left or progressive activists?

It is important to get the right balance in assessing the political consequence of a Meloni victory. First of all, there has already been neo-fascist participation in Italian post-war governments – Berlusconi had Fini in one of his governments. Secondly, although her party may well be the biggest single political party and will certainly be so within the right-wing coalition it will still be reliant on an alliance with two other right-wing parties in order to form a government. It is not even close to getting a majority big enough to govern alone. Thirdly, the second biggest party in the right-wing coalition, the Lega, is just as racist on migrants or on culture war issues like gay or trans rights. On the ideological issue of protecting white national (catholic) Italian identity against the migrant or ‘Islamic replacement’ threat, there is little difference between the FdI and the Lega. Fourthly, although it has retained the fascist era tricolour flame emerging from a coffin (i.e. a symbolic continuity with Mussolini) on its electoral symbol there has been a campaign similar to that of Le Pen to detoxify her political current of openly fascist policies and elements.

Although there are comings and goings between openly fascist militants from Forza Nueva and CasaPound and her party with some even ending up on electoral slates, she is careful to distinguish FdI from them. Investigative TV programmes have uncovered some ‘private’ fascist anniversary celebrations so there is a degree of ideological continuity. At the same time, Meloni has gone out of her way during the campaign to defend her mainstream pro-Western Bloc credentials, her criticism of Putin on Ukraine and her willingness to work with the European Union. To a degree Salvini is much softer on Putin, questioning the effectiveness of sanctions.

Exaggerating the imminent fascist threat is a big part of the PD’s electoral playbook. Letta, the PD leader, wants the election narrative to be a showdown between Meloni’s threat to democracy and progressive ideas and his party’s robust defence of them. He even tried to get the TV debates to be limited to a duel between both parties. As some of the Italian radical left media have commented this allows attention to be diverted from the PD’s total support for Draghi and his neo-liberal programme. It allows the PD to avoid any examination of their contribution to the conditions which allowed Meloni to win more support. Just as with Le Pen, Meloni has won some support from the sort of working class voters that formerly voted en masse for the PD and its predecessors.

Nevertheless, Meloni does represent a real threat of a drift towards Orbán-style populist governments. Salvini recently praised Viktor Orbán’s family policies as the most advanced in Europe! Along with Salvini as the new Home Secretary, she will launch a renewed assault on migrants trying to cross the sea to Italy. Like the new British PM, she will try and forcibly repel the boats. Although she is not arguing for the repeal of abortion legislation Meloni is in favour of making women’s choices more difficult. In the Marche region (Ancona) the FdI governor has intervened to delay the procedure for women to decide and anti-abortion counsellors are being proposed to ‘assist’ the decision-making process. As prime minister, she would propose axing the citizen’s income welfare payments which, while insufficient, does represent a real benefit for working people. Her coalition would support the regressive ‘flat’ tax that the Lega is championing. At the moment she is presenting herself as a figure of fiscal rectitude, agreeing with Draghi’s budget spending limitations.

Her government would continue the steady erosion of anti-fascist historical understanding that used to be the consensus in Italy. So in answering questions about the fascist period she says that although the racial laws and political bans were wrong Mussolini did some good things. Fascist repression during the liberation war is increasingly being ‘balanced’ by exaggerating acts of violence committed by communists following the war in North East Italy. In 2018 Meloni declared that the celebration of Liberation Day, also known as the Anniversary of Italy’s Liberation from Nazi-Fascism on 25 April, and Festa della Repubblica, which celebrates the birth of the Italian Republic on 2 June, should be substituted with the National Unity and Armed Forces Day on 4 November, which commemorates Italy’s victory in World War I. She said that Liberation Day and Festa della Repubblica are “two controversial celebrations”.

In many ways, the real threat of Meloni is how she will favour what we have identified on this site as forms of creeping fascism. Already the post-fascist hard right has captured a majority inside the right wing coalition, to the extent that Silvio Berlusconi and his Forza Italia party are presenting themselves as the moderate wing of the alliance. The political centre of gravity has moved to the right, as it has done in Britain following Brexit.

Meloni’s proposal, supported by her coalition partners, for the people to elect the president – to create a semi-presidential system like in France would be a serious attack on democracy. It would require a big majority for the right-wing coalition as it requires changing the constitution. Parties with a fascist or a populist heritage obviously favour a more presidential system

One big mistake I have seen on Italian social media and TV in confronting Meloni is to sneer at her lack of intellectual qualifications, that she is not sufficiently educated to be Prime Minister. Her very appeal to a number of voters is that she does not come over like a lawyer, professor or manager, like most other politicians in Italy, even if she has been a professional politician for many years. During the campaign, she has gone out of her way to appear both as an incumbent Prime Minister and as someone who is accessible and not confrontational. In Cagliari the other day when an LBGT protester got on the stage she prevented a violent removal by security and talked calmly with him. When a single dad wrote to her about her position opposing gays and single people adopting children she agreed to go and eat a pizza with him. So far her campaigning has led to an increase in polling support.

Salvini has accepted that if the FdI gets the biggest vote within the right wing coalition then she will get its support to become Prime Minister. This is a huge change in the relationship of forces on the right over the last few years. Salvini was seen as the front-runner before. His hamfisted manoeuvres at ending the first Conte government, his lack of clarity on Covid measures, his party’s material assistance from the Putin regime and his participation in the Draghi government have all weakened his position viz a vizMeloni.

The chances of a hard-right victory in the election are greatly aided by the new electoral system which was brought in by the left of centre parties. It combines the first past the post system of 37% with a proportional system for the rest with a threshold of 3% for a single party to get into parliament. You cannot split your vote between different parties for the first past the post and the proportional contests. It obviously pays to have a strong coalition for the first past the post part. Given that there is no corresponding coalition of the anti-right wing forces then the right-wing coalition will win a large majority of the first past the post seats. The big reduction in the number of constituencies – down to 400 for the lower house and 200 for the Senate weakens democratic representation and gives minority parties even less chance of parliamentary groups.

The Democratic Party – a prop for the establishment

Letta’s PD was the most enthusiastic supporter of the Draghi government and places its campaign in the continuity of this framework. This is the poster it put out following the fall of Draghi (see right)

It reads: Italy has been betrayed, The Democratic party defends Italy, Are you with us?

The PD was so keen on the national unity government that it tried to do everything to form an electoral coalition with small bourgeois ‘centrist’ parties like Carlo Calenda’s, Azione. To great fanfare, it proclaimed this new alliance. A few days later the engagement had been broken. Letta wanted to have a bit of a left face too so wanted the Greens, a pro-European group and one of its left satellite groups, Sinistra Italia, SI (Italian Left) to come on board too. Calenda did not want to be in a coalition with a group like SI which had opposed the Draghi government. He then jumped into the arms of Renzi, the ex-PD leader but now with his one mini group, Italia Viva.

Ironically Calenda had previously said he would never ever work politically with Renzi. But he needed the automatic entry into the elections that Renzi’s party would give him, otherwise, he would have to find enough activists to collect 40,000 signatures. So this new coalition is desperately trying to talk up a so-called ‘third pole’. It hopes to draw voters from the PD who dislike linking up with any left grouping to its left and to moderate voters worried about Meloni/Salvini. Currently, this group has over 6% and is only behind Berlusconi by a couple of points. Unless it gets above 10% it will have little influence, it would require the right-wing alliance to do a lot worse than expected so that a new government coalition could be put together.

Even if the current hard-right coalition wins there is still a possibility that its unity might not survive a crisis and it will be Draghi time again. Berlusconi can turn on a sixpence if it is in his interests. Unsurprisingly one of his main electoral proposals is around making it harder for the law to pursue fraudsters like him.

The PD for its election campaign has taken out of the back drawer some progressive measures that it made little effort to put forward or implement during its recent period in government. It is proposing that teachers get paid at the European average level and that there should be more investment in schools. It is also supporting laws against homophobia and same-sex adoption.

M5S – can the rump bite back?

With around a third of the vote and 339 MPs in 2018, the M5S seemed to be achieving its aim of removing the political caste and completely disrupting the political system. Today the rump led by Conte has 159 MPs. Its MPs have continually split off to the right and left over the last 5 years. For a party that claimed to be neither left nor right it has actually governed with Salvini’s right wing and then the PD’s moderate left. For a party that proclaimed it was doing politics completely differently, it soon found its MPs did not like the stringent rules on only two terms and on handing over a big chunk of your salary to the party to use as funds or to help start-up businesses. The final big split was former leader, Di Maio, who has a new party Impegno Civico (Civic Engagement) which has joined the PD coalition. If you thought these people could not sink even lower, Beppe Grillo even concocted a little show of distorted and deformed figurines of Di Maio and other ‘traitors’ on his website.

However, the electoral programme Conte puts forward has ‘left face’. It defends and calls for increases in the citizens’ income and puts forward a shorter working week. In some respects, it is as left-wing at least on paper as the PD. Several progressive people I know have said they will vote for this. Indeed the left wing and satellites of the PD were quite keen on including the M5S in the coalition. Even the radical left UnionePopulare (Peoples Union) of Luigi Di Magistris were keen on dealing with them. It does seem that the ‘left’ turn is having a positive effect on their polling – they are outscoring the Lega and Forza Italia with 15%.

Is there a real left alternative?

In early July before the elections were called Luigi Di Magistris, the former radical mayor of Naples came to speak to a smallish crowd in Cava dei Tirreni where I was staying. The sound system was terrible but he did well to pitch his message about the need for a left alternative, including in elections.

Once the elections were called he set about organising a left coalition, modelled rather on Melenchon’s French coalition which did well in the recent parliamentary elections there. The main forces are a small group of MPs called ManifestoA who came out of M5S, the remaining forces of RifondazioneCommunista – the last independent political current to the left of the PD to have parliamentary representation in 2008 – and Potere al Popolo (Power to the People), a left group formed in 2017. It finds some support too from the rank and file trade union currents (Cobas).

The first major challenge was to actually get on the ballot. You need 37,000 signatures if you do not already have representation in parliament. Given this was a snap election called over the summer holiday season this was quite a tall order. The government refused to allow digital signatures despite this becoming more used now within the notoriously cumbersome Italian administration. People also had to submit the signatures to the local authorities where they resided. Many people are on holiday in August. Some offices were actually closed! If you include the sweltering heat this was not an easy task. Already it has been a small political victory that the signatures were collected and it shows there is a political space for such a current.

The three central planks of the Union Popolare platform are:

- build peaceful international relations, no to military spending and no to war.

- a minimum salary of at least 10 euros an hour, extend the citizen’s income, stop precarious and informal work, and abolish the Jobs Act (this took away some labour rights)

- a real ecological transition through huge investment in renewables, a plan for water security, stop property speculation and the big useless infrastructure projects like TAV (high-speed rail link in Piedmont), popular control of common goods, starting with water and essential services such as health and education

As can be seen, it takes a left pacifist position on Ukraine, refusing to support the resistance of the Ukrainian people. Within the coalition, there are currents in Rifondazione which support the Donbass ‘republic’. There has been some adaptation in the way demands around Covid inquiries are raised to those No Vax people and others who saw public health measures as repressive.

What is important is that the campaign goes beyond a grouping of the leaderships of the different groups and can begin to develop a movement that can be useful and dynamic inside any opposition that will develop against the anti-working class policies of whichever government emerges from the September 25 election.

Nevertheless, the overall thrust of Union Popolare is favourable to building a fighting alternative to the PD’s management of the capitalist system. We have to oppose the false argument that the fight is just with stopping the neo-fascist Meloni and therefore the only ‘useful’ or tactical vote is to back Letta and the PD. Unfortunately, leading writers at the daily communist newspaper, IL Manifesto, argue along those lines. Prominent members of a left-wing trade union opposition like Cremaschi also support the slate. The comrades of Sinistra Anticapitalista (Anticapitalist Left) have called on people to vote for it. At the moment the polls give the UP 0.7% which suggests it will be difficult for it to get past the 3% threshold necessary to get into parliament.

Dave Kellaway is on the Editorial Board of Anti*Capitalist Resistance, a member of Socialist Resistance, and Hackney and Stoke Newington Labour Party, a contributor to International Viewpoint and Europe Solidaire Sans Frontieres.