‘Tariffs are a beautiful thing to behold’: A Marxist analysis of protectionism and the crisis of global capitalism

“Tariffs are a beautiful thing to behold,” proclaimed Donald Trump on his Truth Social account. But as the saying goes, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Judging by the global reaction, few outside Trump’s inner circle share this aesthetic sentiment. Since April 2 — declared “Liberation Day” by the president — his sweeping new tariffs have thrown the international economic order into turmoil.

A universal 10% tariff on all imports took effect on April 5, followed by additional country-specific duties — 34% on Chinese goods and 20% on imports from the European Union — implemented on April 9. When China announced retaliatory tariffs on US goods, Washington responded by raising the levy on Chinese products to a staggering 104%, escalating the trade confrontation. Even Serbia was not spared, slapped with a 37% tariff on its exports to the US, a move that baffled Serbia’s pro-Trump admirers and prompted officials in Belgrade to seek clarification from Washington.

The method behind the tariff assignment has little to do with subsidies, tax policy or non-tariff barriers. It follows a mechanical logic: divide the US trade deficit with a country by the total value of imports, then halve the result. For countries with large and persistent trade surpluses with the US, this may seem internally consistent. But when applied to others, the logic collapses.

Serbia is a case in point. According to the Statistical Office of Serbia, the country exported $556.9 million to the US in 2023 while importing $588 million, a modest trade deficit. The same pattern held in 2022. Yet Serbia has been slapped with a 37% tariff, as if it were a major surplus economy. The mismatch lays bare the arbitrary and coercive logic of the new regime.

From a Marxist perspective, these measures are not about rebalancing trade but enforcing imperial hierarchies. The policy reflects power, not data. Serbia, despite its deficit, has been cast as collateral in the broader drama of US capitalist crisis management. The aesthetic of protectionism masks a geopolitical operation, in which tariffs are deployed not to protect national industry, but to reassert control in an increasingly fractured world economy.

The perils of peripheral integration

The Serbian economic community agrees that the direct effect of the new US tariffs on Serbia is negligible. As mentioned, Serbia exported only $556.9 million worth of goods to the United States in 2023, accounting for less than 2% of its total exports. A 37% tariff on this modest trade volume may hurt specific companies, but it poses no systemic risk to Serbia’s economy. The real threat lies elsewhere — in the ripple effects these tariffs may produce through Serbia’s export dependency on Germany.

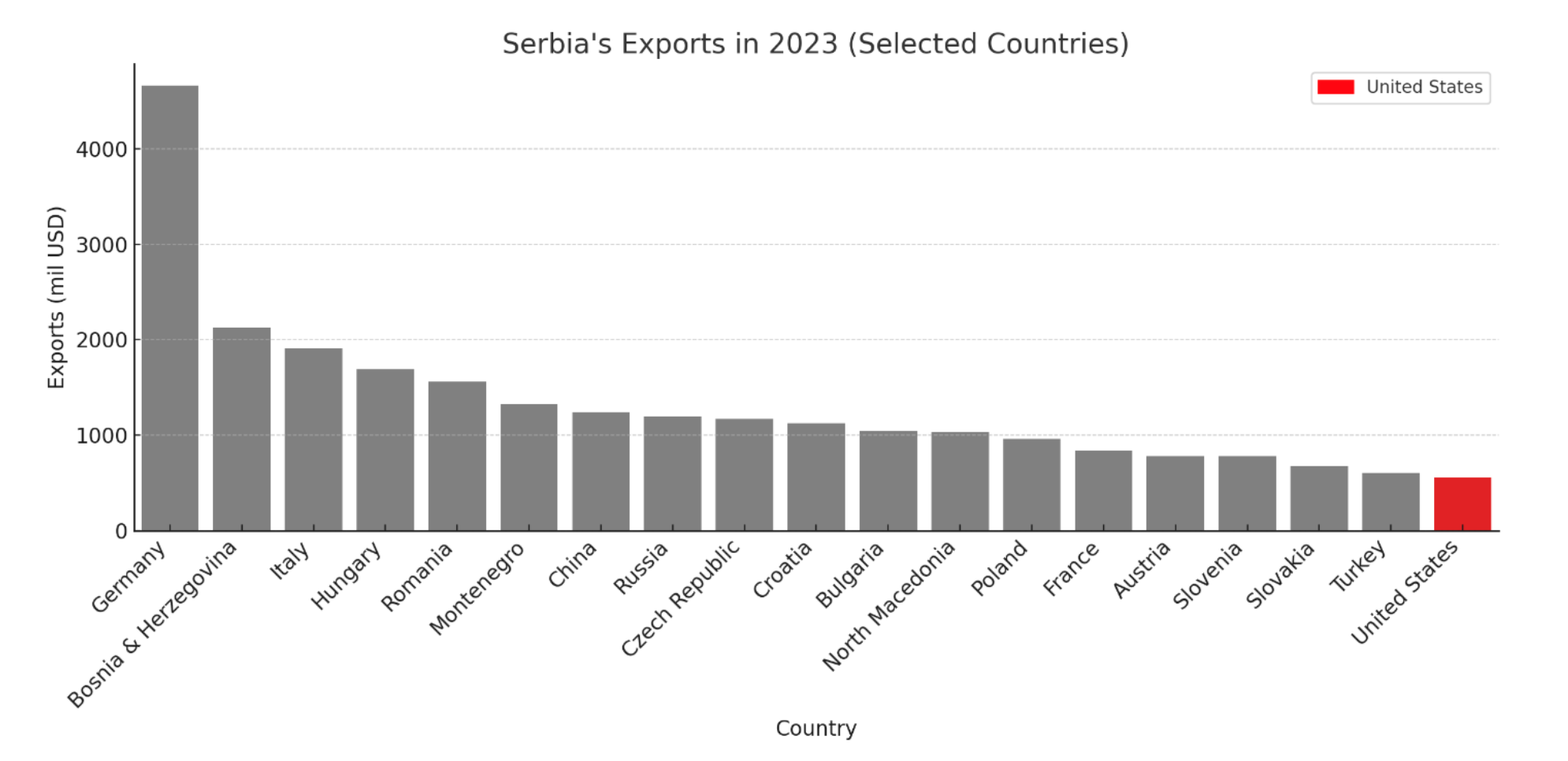

Germany is Serbia’s largest trading partner by far, absorbing over €4.3 billion worth of Serbian exports in 2023 — more than 16% of total export volume (Figure 1 below). Crucially, this trade is not composed of final consumer goods, but intermediate inputs for German industrial production. The most significant Serbian exports to Germany last year included rotating electrical machines (18.7%), electrical distribution equipment (13.9%), parts and accessories for motor vehicles (7.9%), and railway vehicles and components (4.6%).

In other words, Serbia functions as a specialised supplier to the German manufacturing sector, particularly the automotive industry, which is now directly targeted by US tariffs: 20% on general EU goods, and a punitive 25% on imported vehicles. Covering everything from cars and auto parts to pharmaceuticals and machinery, the US was Germany’s biggest trading partner in 2024, according to the statistics office, with 253 billion euros worth of goods exchanged between them. If German carmakers scale back production or shift supply chains, Serbia’s industry will feel the shock.

This is not a theoretical scenario. LEONI Srbija, for instance, produces cable harnesses for premium-class vehicles made by the world’s leading auto manufacturers. The company employs about 10,000 workers, making it one of Serbia’s largest industrial employers. It exports 100% of its production, and in 2023 ranked among the top five Serbian exporters. LEONI also collaborates with around 700 local suppliers, creating extensive linkages across the economy. A contraction in German auto exports could result in downsizing at LEONI, with cascading effects on employment, local subcontractors, and regional development.

This illustrates a fundamental truth of dependency theory: Serbia’s industrial structure is not designed to meet domestic demand but to serve the accumulation needs of the capitalist core. Value is added here only to the extent that it facilitates value realisation elsewhere. When accumulation in the centre is disrupted — whether by crisis, protectionism or political conflict — the periphery is exposed. Its prosperity is conditional, not sovereign. Samir Amin noted in Unequal Development that dependent integration into global capitalism creates a structure of vulnerability, where growth is tethered to decisions made in boardrooms far beyond national control.

These latest developments confirm the empirical findings I presented in Serbia as the Super-Periphery of Europe: Growth Without Quality and Transformation (2024), where I argued Serbia functions not merely as a periphery, but as a super-periphery — an economy structurally locked into low-value, dependent growth trajectories with minimal prospects for qualitative transformation or autonomous development. This reinforces the subordinate position of the Serbian economy in the global division of labor, where even integration into industrial supply chains serves primarily to enhance capital accumulation in the core, not to foster developmental convergence in the periphery.

Tariffs and the logic of capitalist accumulation

Trump’s advocacy for tariffs is more than a populist talking point; it is a political response to contradictions within global capitalist accumulation. His argument works on two levels. On the surface, it invokes fairness and sovereignty. Beneath, it expresses anxiety over a system increasingly reliant on globalised production and financial abstraction.

Trump claims the US is being “taken advantage of” by countries with trade surpluses — naming China, Germany and Mexico as culprits that distort trade through subsidies, currency manipulation and tariffs. This, he argues, harms US workers and producers, resulting in persistent trade deficits.

What this account ignores is the structural function of the US dollar. As the world’s primary reserve currency, the dollar places the US in a unique position. It can run sustained trade deficits without facing balance-of-payments crises. Other countries export goods to the US not due to weak negotiations, but because they need dollars — to service debt, stabilise exchange rates and accumulate reserves. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) scholars correctly point out (even if their broader prescriptions are debatable) that the US is a monetary sovereign. It issues the global currency, faces no external constraint on its supply, and settles debts in its own units.

Thus, global trade is not an exchange of goods for goods, but of goods for claims — namely US Treasury securities and dollar reserves. Critics from Marxist and post-Keynesian traditions note that this amounts to a structural exchange of material output for fiat tokens emblazoned with US ruling-class saints: presidents, a Treasury boss (Alexander Hamilton), and a polymath who never ruled but helped build the system (Benjamin Franklin). The arrangement enables the US to consume more than it produces and finance its global dominance through a currency others must hold. Far from being exploited, the US enjoys what former French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing famously called an “exorbitant privilege”.

Trump’s demand that countries buy more US goods while simultaneously threatening sanctions against those who de-dollarise (such as BRICS countries: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) reveals an internal contradiction. For the dollar to maintain its hegemonic role, others must sell more to the US than they buy — accumulating dollar reserves. Trump’s vision turns this logic on its head. The contradiction is not personal, but systemic: a reflection of a global economy stretched between the imperatives of imperial control and economic nationalism.

This contradiction has two effects. First, it deepens financialisation in the US, where capital abandons productive investment for speculative activities — propped up by foreign demand for dollar assets. Second, it offloads adjustment costs onto the periphery, where states lack the privilege of issuing a global reserve currency. In this light, Trump’s narrative of trade injustice reverses reality. It is not the US that suffers from the current order, but countries structurally tethered to a system they cannot control.

Still, Trump’s rhetoric resonates because parts of the US, particularly the industrial Midwest, have experienced real economic dislocation. As Janesville: An American Story shows, the closure of a single GM plant can unravel entire communities. Boris Kagarlitsky notes in The Long Retreat, even capitalism’s metropoles have become victims of their own neoliberal designs. But this is not due to US weakness — it is the result of an economic structure tilted toward finance and consumption at the expense of labour and production. Tariffs, in this sense, are less a solution than a spectacle, redirecting blame while leaving structural causes untouched.

The second pillar of Trump’s case — that dependence on foreign goods undermines domestic industry — deserves closer attention. It reflects a deeper transformation: decades of deindustrialisation and the erosion of high-wage manufacturing employment. But his across-the-board tariff response lacks historical grounding or strategic coherence.

From a Marxist perspective, protectionism has historically played a role in capitalist development. Samir Amin and other dependency theorists argue tariffs have been tools of primary accumulation and industrial takeoff. They were selective and temporary, designed to shield nascent industries until they became globally competitive. The goal was not autarky but a controlled insertion into global markets on more favourable terms.

Marxist economist Rudolf Hilferding observed more than a century ago that free trade evangelism typically follows successful industrialisation. Britain, for instance, had relied on high tariffs to develop, only to champion free markets once its supremacy was secure — a classic case of “kicking away the ladder.”

Trump’s use of tariffs, by contrast, lacks any developmental rationale. They are not targeted toward strategic sectors, nor linked to investments in innovation or infrastructure. Many apply to goods the US no longer has the capacity or interest to produce. As such, they are unlikely to spark industrial renewal or create stable employment. Rather, they function as political theatre — a reactive gesture from a capitalist core grappling with the limits of globalization.

As Michael Roberts points out in his latest piece, the hope that tariffs will revive US industry and create new jobs is unfounded. Employment in the manufacturing sector has been declining since the 1960s, primarily due to falling profitability and technological displacement of labour — not trade liberalisation. Even if exports increased enough to close the trade deficit, which is highly unlikely, the share of industrial workers would rise only from 8% to 9%.

If Trump truly wants to restore the industrial base, huge investment is needed. But US companies outside the tech “Magnificent Seven” are already facing low profitability and are unlikely to invest — except perhaps in military production funded by government contracts. In this context, tariffs are not a tool of renewal but a symptom of systemic impotence.

Strategic protectionism as capitalist crisis management

If Trump’s tariffs appear irrational from the standpoint of conventional economics, they make far more sense when viewed as responses to the deeper contradictions of global capitalism. From a Marxist perspective, protectionism today reflects not merely incoherent populism, but a systemic effort to manage a global order that no longer delivers reliable returns for capital.

At the root of this crisis lies what Karl Marx identified as the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. As capitalists invest more in machinery and technology (constant capital) and relatively less in labor (variable capital), the overall rate of profit declines — even if the mass of profit continues to grow temporarily. Empirical studies by Michael Roberts confirm this trend in the US economy. His analysis shows a 27% fall in the rate of profit for non-financial corporations from 1945 to 2021, with pronounced declines during periods of rising investment in constant capital. This validates Marx’s insight: the capitalist drive to increase productivity ultimately undermines profitability.

To counteract this tendency, capital resorts to various strategies. It intensifies labour exploitation, relocates production to cheaper labour markets, invests in technological innovation, inflates asset bubbles, and — when under duress — retreats behind protective barriers. Trump’s tariffs represent such a retreat. By raising the cost of foreign goods, they aim to carve out a protected space for US capital, shielding it from more productive or lower-cost competitors. The tariffs also serve to shift the burden of the crisis onto rival capitals — above all, China and the European Union — in the hope that US producers can regain some of the competitive ground they lost in the era of hyper-globalisation. The goal is not economic nationalism per se, but the temporary restoration of profitability.

Yet, these measures do not resolve the underlying contradictions of accumulation; they merely redistribute its effects. The structural tendency toward overaccumulation and profitability crisis remains. In the absence of a comprehensive industrial policy, the breathing space created by tariffs is not used to revitalise production, but rather to sustain the circulation of fictitious capital.

This is where the strategy of share repurchases — or buybacks — enters the picture. In the current phase of financialised capitalism, falling share prices are not necessarily a threat; they are an opportunity. When markets respond to tariff announcements or economic uncertainty with a decline in stock valuations, corporations often respond by using excess cash — or low-interest credit — to buy back their own shares. This artificially inflates earnings per share (EPS), props up share prices, and secures executive compensation, even when underlying productivity remains stagnant.

Now that Trump has temporarily backed off for 90 days (with the notable exception of China, where tariffs have reached an astronomical 125%), some cynical followers of conspiracy theories claim the tariff announcement served precisely this purpose: to allow US companies, and other well-informed speculators, to buy shares cheaply before the US stock market rebounded by 10% on April 9 — the largest single-day increase since 2008.

Another effect of this dynamic is seen in how corrections on capital markets — provided that business profitability remains nominally unchanged — can contribute to a rise in the profit rate. As the value of shares and other assets falls, the market value of total capital declines — that is, the denominator in the profit rate formula shrinks. If the mass of profit remains constant, the mathematical consequence is a rise in the rate of profit.

Similarly, from a Marxist perspective, the reduction in the market value of constant capital increases the relative importance of variable capital (labour) in the production process, thereby enhancing the potential for extracting surplus value. In other words, a nominal decline in capital value can act as a systemic rebalancing mechanism, restoring profitability even in the absence of real production growth.

In this system, capital accumulation increasingly bypasses production. Instead of funding technology, jobs or infrastructure, surplus flows into asset inflation. Tariffs and buybacks work in tandem: the former shields domestic capital from global competition, while the latter sustains shareholder value through fictitious capital — asset prices divorced from underlying production.

This shift also reflects a deeper transition. The globalised model of accumulation that dominated the late 20th and early 21st centuries is no longer delivering. The basic mechanism, in which capital from the core exploits cheap labour in the periphery, has begun to exhaust itself. Wages in China and other emerging economies have risen, logistics have become more fragile and politicised, and political consensus in the core countries has eroded. Public patience with deindustrialisation, wage stagnation and dependency on foreign supply chains has worn thin.

Technological advances in robotics, AI and 3D manufacturing now make reshoring technically feasible, but not necessarily labour-intensive. What looms is not a revival of 20th-century industrial capitalism, but a dystopian configuration in which US robots compete with Bangladeshi workers for the same sliver of global value. Trump’s tariffs are less a blueprint for industrial renewal than a prelude to a new techno-nationalist order organised around capital control, technological dominance and regional economic blocs.

The same logic of crisis management is evident in financial markets. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Federal Reserve injected huge liquidity into the system. This intervention stabilised markets in the short term but created vast distortions. By early 2025, the total capitalisation of the US stock market was estimated to exceed its “fair value” by $25 to $30 trillion — an unprecedented divergence between market valuation and real economic output. This was not the return of growth but the inflation of fictitious capital to new heights.

The correction is now underway. Roughly $11 trillion in market capitalisation has already been wiped out, and another $15 to $20 trillion may yet vanish. However, this process is not solely destructive; it serves a systemic function. As capital retreats from risky assets to the relative safety of US Treasury bonds, yields on government debt fall, easing the cost of public borrowing and alleviating major drivers of the federal deficit. In effect, the crisis in capital markets becomes a backdoor mechanism for restoring fiscal space — not through taxation or austerity, but through the disciplining of capital itself. The state gains room to maneuver not in spite of the crash, but because of it.

As Adam Tooze emphasizes in his Chartbook 369, the US Treasury market, encompassing all $28 trillion of it, is the truly systemic bond market. In the normal course of a stock market correction, we would expect to see bond prices rising and yields falling, thereby lowering interest rates and easing pressure on businesses. This reflects the see-sawing, balancing effect of markets operating across assets, where Treasuries serve as a safe haven in times of uncertainty.

Crisis as transition, not collapse

Taken together, Trump’s tariffs, the resurgence of protectionism, the persistence of fictitious capital, and the current stock market correction are not disconnected phenomena. They are linked responses to the systemic contradictions of capitalism — and particularly to the long-term tendency of the rate of profit to fall. They reflect an increasingly desperate attempt by the ruling class to defend profitability and maintain hegemony in the face of stagnation, overaccumulation and political disintegration.

What we are witnessing is not the end of capitalism but its mutation. The neoliberal globalisation of the past four decades is being dismantled, not to make way for socialism or democratic planning but to construct a new regime of accumulation — one more suited to capital’s current needs. This regime will likely be marked by intensified state intervention, regionalised production zones, and a deepening reliance on financial manipulation to sustain capital values. It will not resolve the contradictions at the heart of the system. It will simply displace them, once again, into new geographies, new technologies, and new crises.

In this reconfiguration, peripheral states such as Serbia are not passive observers but collateral damage. The 37% tariff imposed on Serbian exports — despite the country running a trade deficit with the US — exposes the arbitrary and coercive logic of this transition. It signals that the new regime of accumulation will be policed not by rules or multilateral institutions, but by power and geoeconomic intimidation. As capital reshuffles its priorities and blocs harden into protectionist zones, countries such as Serbia find themselves caught in the crossfire — punished not for any economic offense, but for occupying a structurally dependent position within the global system. The crisis, in this sense, is not merely economic. It is a geopolitical sorting process that reasserts imperial hierarchies even as the old liberal order dissolves.