For an ecommunist alternative to degrowth and ‘luxury’ communism

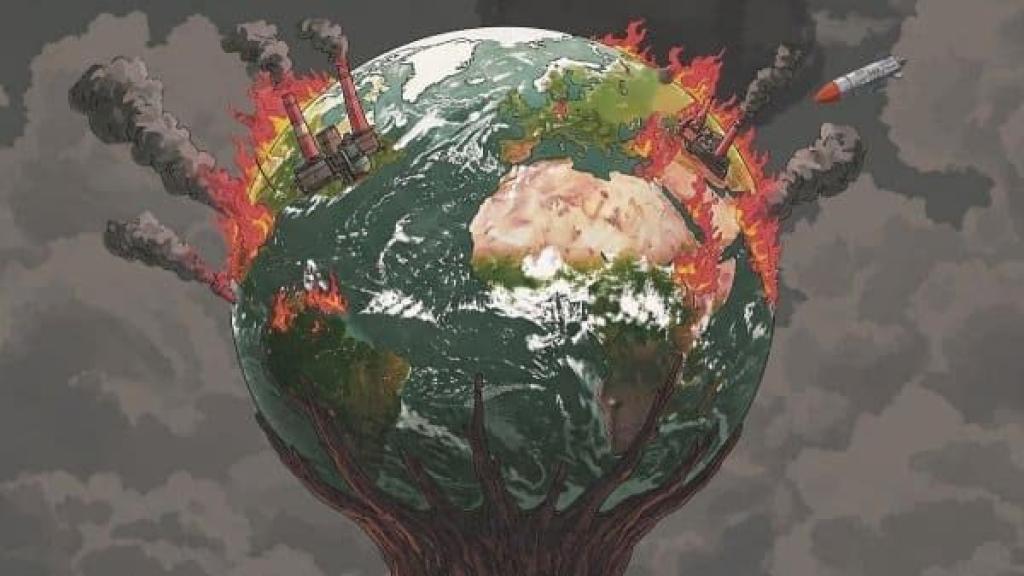

In his new book, Rojo fuego. Reflexiones comunistas frente a la crisis ecológica (Fiery red: Communist reflections on the ecological crisis), Argentine Marxist Esteban Mercatante takes aim at capitalism as the root cause of the “multidimensional” ecological crisis, while engaging in important dialogues with ecological currents such as degrowth and ecomodernism. Against these, Mercatante argues for an “ecommunist” strategy, focused on labour as the agent of both its own emancipation and the qualitative transformation of society’s relationship with nature, as the only means to avoid disaster.

With the book only available in Spanish, Federico Fuentes from LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal spoke to Mercatante, who is also an editorial board member of Ideas de Izquierda (Left Ideas), to discuss some of the key points raised in his book.

Given the already existing and constantly expanding range of literature on Marxism, ecology and the climate crisis, what made you decide to write your book?

It was precisely because this issue has become such an important focus of contemporary discussions. The ecological crisis today is an intersecting issue, which means that this issue and its impacts must be taken into account across different disciplines.

In this book, I was interested in exploring two things. On the one hand, I wanted to introduce a Marxist perspective — which is not as accessible for Spanish-speakers — into the discussion, particularly here in Argentina where the book was published (it has now also been published in Spain). Most ecomarxist works produced in the past decades, from the early contributions by John Bellamy Foster through to the more recent writings of Kohei Saito and Andreas Malm, have been relatively little discussed. Taking into consideration the dialogue that is occurring between revolutionary left activists and ecologists, I wanted to try to synthesise some of these contemporary contributions that put forward an ecological critique. There are also questions that ecomarxists need to further develop their ideas on, and I wanted to contribute to that too.

On the other hand, I want to look at all the ways in which Karl Marx's critique of political economy can help expose the anti-ecological character of capital accumulation. Part of the book reconstructs the different phases of production and circulation of capital, from capital-labour relations to the formation of a world market based on increasingly accelerated flows of commodities and money. This helps us think through how different ecological problems are generated at each stage of this cycle.

Lastly, there is another key question that Marxism has struggled to address — and which we need to debate — and that is how to link our ecological critique of capital to a revolutionary strategy for transcending capitalism and prefiguring a society that can move beyond capital. This is a major weakness in the otherwise important contributions by Foster, Saito and others. More recent attempts have sought to deal with this challenge, for example Andreas Malm’s call for an “ ecological Leninism”. But, as refreshing as his approach is, his view that the revolutionary seizure of power, as the first step towards transitioning to a socialist society, is not on the agenda today leaves his proposal somewhat floating in the air.

What my book aims to do is contribute to what I believe is a fundamental discussion on how to develop, from an ecological perspective, a revolutionary strategy around a communist vision that both seeks to liberate humanity from exploitation and restore a balanced metabolism between society and nature, which form a differentiated unity.

Environmentalists often focus on climate change, but your book situates this issue within a broader “multidimensional” ecological crisis. Could you elaborate on this?

The idea that we face a multidimensional crisis has been well illustrated by the Stockholm Resilience Centre’s study. It sets out a series of planetary boundaries. One involves greenhouse gases and global warming, but it also looks at biodiversity loss, deforestation and land use changes, ocean acidification, air pollution, and several other boundaries. All up, the SRC sets out nine boundaries and a series of critical thresholds for each that should not be crossed to avoid accelerated deterioration with unforeseeable consequences for a “tolerable” — let alone desirable — human life.

This is what I mean by a multidimensional ecological crisis. It is important to raise this because many of the solutions proposed by green capitalism advocates to deal with ecological problems tend to focus on a single issue — mainly climate change. This generates proposals that, while seeking to fix one issue, end up negatively affecting others. For example, an energy transition requires extracting minerals such as lithium on a large-scale to produce storage batteries. But this leads to more resource extraction, which uses a lot of water and alters ecosystems in dependent countries such as Chile, Bolivia and Argentina.

Why do you say that the cause of this crisis lies in “capitalism’s DNA”?

Capitalist society is characterised by the drive to convert nature into an object that can be valorised. The same occurs with labour power. Dependent on capital, labour is forced to continuously produce as much value as physically possible. The law of value, when extended to nature, implies prioritising the development of techniques that can facilitate extracting the greatest quantity of resources (whether agriculture and livestock, tree plantations for timber, fish farms or minerals) for the lowest price. Nature is “valued” solely in terms of the cost of appropriating it. Meanwhile, certain areas are set aside as “dumping grounds” for waste, which is deemed a “service” capital can exploit.

Under capital’s logic, environmental impacts have historically not been factored into the business equation. In traditional economic theory, they appear as an “externality” — something not intrinsic to business running costs. Capitalist states have sought to “correct” this through environmental governance, with measures including taxes, fines and other mechanisms such as carbon credits. But these do not fundamentally change the relationship between capital and nature, or the negative impacts of various productive activities. They simply make companies pay for polluting by putting a “price” on it, while doing nothing to repair ecosystems.

Capital prioritises short-term profitability, even if that generates burdensome consequences in the medium or long term. Today we are seeing some of these unforeseen consequences from past actions, such as climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions from preceding centuries. Yet even now, when we know about these consequences, we see oil companies, faced with the prospect of winding up their operations, rushing to extract every last drop of oil, thereby making the consequences even worse. This behaviour — driven by a viewpoint that Saito, borrowing a phrase from Marx, aptly describes as “ after me the deluge” — undermines the prospects of intergenerational sustainability. Sustainability has become a kind of mantra for many companies, but it is mostly pure greenwashing.

The logic of capitalism leads to attempting the “ production of nature”, as geographer Neil Smith put it; that is, a nature entirely mediated by the social, by capital. But attempting this — and Smith somewhat underestimated these limits — is fraught with tensions, because natural metabolic processes are very complex. Capital’s efforts to subsume them generate unpredictable consequences, the impacts of which are proportional to the efforts to dominate nature. This is what Engels had in mind when he spoke of the “revenge” of nature against domination attempts that ignore the limits imposed by nature’s laws and instead seek to “twist” them for profit.

In the book’s introduction, you explain that the environment is very present in state policies and business practices. But, borrowing a phrase from Ajay Singh Chaudhary, you argue what reigns today is “ right-wing climate realism”. What do you mean by this?

Chaudhary correctly points out that a significant section of the ruling class helps ensure climate policies are cosmetic or impotent. Not because it is denialist but because it believes it can survive accelerating deterioration as climate events become ever more recurrent and catastrophic. Chaudhary puts forward the idea of an “ armed lifeboat”, in which those with sufficient resources can — and do — invest in underground bunkers equipped with all the basic necessities, while simultaneously investing in technologies that might one day allow a chosen few to evacuate Earth.

The obvious question is how much of this is feasible and how much is pure science fiction, at least for now. But I am interested in the idea that these sectors see no contradiction in acknowledging the ecological crisis while refusing to promote initiatives that could do something about it. It debunks the idea we so often hear that “ we are all in this together.” When it comes to the ecological crisis, we are not all in this together. That is why the working class and poor must promote our own solutions, because no section of the ruling class — denialist or non-denialist — is going to do that for us.

Has the rising global influence of the far right — we now have far-right presidents in Argentina and the United States — tipped the scale more towards denialism, whether in terms of national policies or in international forums such as the COPs? Related to this, how do you interpret the rise of ecofascist tendencies within this broader far right?

Undoubtedly, as the extreme right grows stronger globally, the voices of denialism, which reject the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda and want to disengage from the COPs, are gaining strength. But divisions and tensions are arising among them, which means things are not so clear cut. Until two months ago [US President Donald] Trump and [tech billionaire] Elon Musk were allies; now they are at loggerheads. The former has always been a denialist, while the latter champions electric automobiles. As a result of this clash, it seems we will have cuts to public funding for electric vehicles and associated technologies. But this could have gone a different way. As we have often seen, the extreme right, with its very strong denialist component, has not necessarily translated its ideas into coherent policies. With each case, we have to look at what different alliances are formed, what concessions have been made to sectors of big capital, etc.

It is important to note that denialist attacks have, in their own way, helped legitimise the stagnant agenda of various multilateral forums. There is an increasing trend among left and progressive sectors to defend them against attacks from the right, and even silence criticisms they once made of the miserliness, impotence and cynicism that pervades these spaces. These forums, along with corporate “ green capitalism”, have gained some legitimacy from being attacked by these denialists. We must be alert to this danger.

The emergence of ecofascisms, though still somewhat incipient, is also important to note. As the consequences of the ecological crisis worsen, we should not be surprised if “emergency measures” take on an evermore overtly ecofascist character. For instance, we can see how the far right tries to draw a link between xenophobia and the view that the climate crisis will lead to future threats of increased immigration waves.

We must be clear that if the working class does not develop an independent, revolutionary political perspective capable of responding to social needs and showing a way out of these crises by tackling the root cause — capitalism — then it is increasingly likely that reactionary solutions will be imposed.

Alongside the growth of ecofascist positions, we are seeing an increasing promotion of apocalyptic visions, particularly among some left sectors who believe that a discourse of environmental catastrophism or collapse will mobilise people. What do you think about this?

This idea of collapse can take different forms.

One is a rehash of the old mechanistic catastrophism that certain anti-capitalist left sectors ascribe to any crisis (whether economic or ecological). Such crises are viewed as objective factors to help compensate for difficulties in the subjective terrain, that is, for building a revolutionary social force. Such currents have appeared throughout the revolutionary movement’s history. It is not surprising that the ecological crisis provides them with some fuel.

Another current believe it is impossible to sustain any type of social organisation that is so dependent on scarce fossil fuels, and therefore resource depletion will inevitably impose reduced social demand. For them, globalisation will become unsustainable and force a return to local, communal spheres. Such thinking is often tied to a certain version of degrowth — not as something desirable, but something that will inevitably be imposed on us.

Lastly, the idea of collapse can also take the form of a kind of generalised common sense or “ structure of feeling”, which is reinforced by the rising recurrence of climate disasters. Out of this has emerged the idea that we have run out of time and are already inexorably heading towards catastrophe. Rather than triggering anti-systemic mobilisations, this leads to paralysing pessimism.

Whether arising as a result of mechanistic thinking or pessimism, collapsism is an obstacle for action. Instead, we must fight against the impending catastrophe.

Some argue that as Global North countries are largely responsible for the crisis they should bear the main responsibility, while Global South countries can use natural resources as they want to develop their economy. What is your view of this complicated issue, often called “ common but differentiated responsibilities” or, in its most radical form, climate justice?

This view contains an important critique of systemic inequalities. This is something formally recognised in international governance, for example when differentiated greenhouse gas emission targets are made on developed and developing countries, respectively. Global climate justice movements have helped bring many of these issues to the fore. Ecological currents have also developed concepts such as unequal ecological exchange and ecological debt.

However, the problem for dependent countries, whose economies remain dependent on the Global North’s, is that “capitalist development” has become a pipe dream, something recent history shows is impossible for them in an imperialist world. In my book El imperialismo en tiempos de desorden mundial (Imperialism in times of world disorder), I look at how the formation of global value chains has condemned dependent countries to a “race to the bottom", in which each strives to offer more flexible labour and environmental regulation and tax incentives to attract investment. The result is that even countries with some success inserting themselves into the many links within existing value chains have not managed to develop their economies in any significant way. Rather, we see increasingly unequal value distribution along these chains, with richer countries taking the lion's share.

That is one issue. The second issue is we must question what development means in times of ecological crisis. It must be clearly stated that non-capitalist perspectives are the only way, first, to break the chains of dependence and plunder, and, second, promote a society that can fully satisfy social needs while maintaining a healthy metabolism between humans and nature. Capitalism cannot do this.

You write that “different currents within critical ecology and ecosocialism give very different answers to what should be the central coordinates guiding the organisation of post-capitalist societies.” What are these main currents?

Broadly speaking, these currents today tend to be polarised between proponents of degrowth and advocates of an anti-capitalist or ecomodernist accelerationism.

The main target of degrowth — as its name suggests — is economic growth, which is identified as the main cause of the ecological crisis in its multiple dimensions. Significant space is dedicated to the “ ideology” of growth in most of these writings. Many degrowth texts spend time explaining how gross domestic product (GDP) growth became an incontrovertible measure of economic success, and how all economic policies since the 1930s are based on stimulating continuous growth. Degrowthers argue that you cannot put an equal sign between GDP growth — or more specifically GDP per capita — and wellbeing. They say, beyond a certain point, higher GDP per capita does not equate to an equivalent improvement in people’s lives.

It is worth keeping in mind that these authors write from, and think about, their situation in rich countries. Their argument that what we face today is over-consumption, and that resource extraction far exceeds the planet’s capacity to replenish what is extracted, makes sense when we talk about developed countries. They raise concepts such as the “ imperial mode of living”, which says rich societies live beyond sustainable limits, and do so at the expense of the rest of the planet from which they extract resources and offload the costs of environmental impacts.

This raises an interesting issue by inserting imperialism into the ecological question. But, at the same time, it contains several problems. For instance, discussion tends to end up going down the path of questioning consumption rather than production itself, which, beyond any intentions, slightly blurs the systemic root of the problem. Also, the working classes in rich countries end up being viewed as participants in this “imperial mode of living” — or, at least, are not explicitly excluded. This is despite multiple indicators showing a marked deterioration in their living standards in recent decades, due to privatisation and global economic restructuring. This is not clearly incorporated into degrowth perspectives.

This does not mean the burden of responsibility should be equally shared. Inequality is a very important aspect of these views: the idea that the ultra-rich — with their planes, yachts and mansions — share overwhelming responsibility for creating such a large ecological footprint. Moreover, questioning the notion of economic growth as an end in itself, as degrowthers do, is important. Productivist ideas have gained a foothold even among some anti-capitalist sectors, despite being a dead end. So, such warnings are valuable.

But there are big weaknesses in degrowth perspectives in terms of developing consistent alternatives. They say there must be qualitative changes in how things are produced, but struggle to come up with concrete measures. The quantitative emphasis — reducing the scale of production and consumption — is the only thing they clearly articulate.

The common denominator between different visions of degrowth is a vague, and often ambiguous, anti-capitalist stance. Questioning economic growth as an end in itself means opposing a basic aspect of capitalism, because there is no continuous capital accumulation of value if there is no concomitant rise in resource extraction. But it is much more difficult to translate this negative idea into a positive alternative.

There are also differences among exponents of degrowth on the alternative. Some authors, such as Serge Latouche, are directly hostile to the idea of socialism, given the past experiences of the former bureaucratised workers' states, and accuse all Marxists of being productivist. Others argue that a steady-state capitalist economy (in which some sustained measures avoid growth while guaranteeing reproduction at a stable rate) may be possible, and that therefore degrowth and capitalism are not inherently antagonistic. There are also those with more anti-capitalist views, such Jason Hickel or Kohei Saito, the latter of which explicitly advocates for degrowth communism.

Notwithstanding these nuances, what characterises all these visions is their focus on a kind of minimum or immediate program, which may vary a little but is basically conceived as demands on the state. They include some interesting issues we can agree on — such as reducing the working day — but are not combined with a transitional perspective, or something resembling a strategy to transcend capitalism.

Standing opposed to these positions — in an almost mirror-like fashion — is ecomodernism. From this perspective, the answer to the ecological crisis lies in accelerating technological development. Its central diagnosis is that, under capitalism, innovation is unable to fulfil its full potential, as it gets harder to translate it into profitable business models that justify investments. Aaron Bastani’s book Fully Automated Luxury Communism is a prime example. In Bastani's view, freeing technological development from the constraints imposed by capitalist relations of production would make it possible to fully automate production processes.

In this sense, ecomodernism is opposed to reducing metabolism. On the contrary, they argue the need to continue pursuing growth, and perhaps even growing faster, in order to come up with innovations that can solve environmental problems. The problems capitalism generates are simply reduced to a lack of planning. Ecomodernism envisions forms of consumption intrinsic to this mode of production continuing beyond capitalism, thus contributing to their naturalisation and dehistoricisation. Technology is also fetishised. It tends to be given an aura of neutrality, when in fact all new developments and innovations are shaped by class relations.

For ecomodernists, there is almost no limit to the so-called decoupling of the economy from the environment — that is, ensuring the least possible impact in terms of resource extraction and waste production. The expansion of what Bastani defines as “fully automated luxury communism” can therefore apparently occur without encountering any sustainability problems. They base this on the claim that this has been occurring for a long time under capitalism in the more developed countries.

The problem is that, despite undeniable efficiency gains in terms of material impacts, statistics on so-called decoupling mostly leave out the fact that, due to changes in the global division of labour, such countries depend much more on material processes occurring outside their borders; namely, industrial processes in developing countries that are controlled by multinationals based in imperialist countries. What we have is less decoupling than the offshoring of production processes to third countries, through which environmental impacts are “outsourced”. Once we take this “offshoring” into account when looking at ecological footprints, the scale of decoupling is largely reduced, if it does not disappear altogether.

Putting faith in an automated luxury communism based on such weak assumptions can only lead to ruin. Precisely because they do not want to put all their eggs in one basket, they often hedge their bets, saying that if we cannot achieve enough decoupling, then the answer lies in space mining (the extraction of metals from asteroids) and using outer space as a dumping ground for the trash accumulating in increasingly unsustainable ways across much of the planet.

Lastly, ecomodernists think more in terms of eliminating labour than transforming it. Dave Beech views this current as essentially anti-work. This shows itself in the absence of the working class as a subject with any role to play in its emancipation or establishing a different social metabolism. They hope that the system’s contractions, worsened by the kind of accelerationism they propose, will produce a post-capitalism that enables planning, along with the “democratisation” and extension of the consumption patterns of the rich to the rest of society.

Given these patterns cannot be made universal within the finite limits of the planet, it is not surprising they have to conjure up intergalactic solutions to environmental challenges. What we are left with are proposals such as Bastani’s, that offer a (luxury) “communist” variant of the kind of space ravings of Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos.

Against these currents, you argue the case for an “ecommunist” perspective? What is ecommunism? Why and how does it differ from ecosocialism?

The term ecomunismo comes from the title of Ariel Petruccelli’s latest book, which was published in Spanish almost at the same time as mine. I adopted the term because it foregrounds the central issue that ecological Marxism or ecosocialism must emphasise. Instead of debating whether “solutions” will come from technology or reducing metabolisms, we need to organise the needed social forces to attack the foci of ecological destruction: capitalism and the relations of production this exploitative social order engenders.

For many critical ecologists, including even some ecosocialists, the relations of production are a kind of “black box”; a terrain left unexplored or only tangentially mentioned. They miss the centrality of ending alienated relations between the great producing class — the waged labour force — and the means of production. Ecomodernists and degrowers both talk about reducing the working day, albeit for different reasons and motivated by different logics, but what is missing from both is the protagonism of labour — exploited by capital — as an agent in its own emancipation and in the qualitative transformation of society’s relationship with nature.

Ending the monopoly of private ownership over the means of production implies expanding workers’ democracy — the democracy of those who produce and also consume a great part of what is produced — into a sphere currently dominated by capital. Under capitalism, production-consumption is a differentiated unity mediated by the process of exchange, in which social need can only be expressed as a financially-sound demand (and can only appear as the choice of one or another commodity that capitalists have previously decided to produce and sell). As such, only by socialising the means of production can we re-establish a genuine unity of both processes, in which production is based on satisfying social needs — the first step towards any kind of planning. This is a key aspect that can help us break free from the polarised debate between “more” or “less” that has dominated discussions among ecosocialists.

Rationally mastering society's metabolism with nature by collectively deciding what to produce (based on which social needs should be prioritised) does not mean we can avoid difficult decisions around capitalism’s legacy of environmental destruction. But rather than these decisions being made by the private power of capital — backed by governments whose central function is reproducing capitalist relations of production — it will be the producing class as a whole, having regained control over the means of production, which will work out proposals to settle these questions. They will do so while ensuring that three different objectives are met: fully satisfying fundamental social needs; democratising production; and seeking to establish a rational metabolism with nature. Moreover, “expropriating the expropriators” will allow us to recover a broader notion of wealth, which breaks with the idea that abundance must translate into the kind of limitless consumerism that capitalism has promoted to sell ever increasing numbers of commodities.

Post-capitalist ecomodernist mirages envision the end of labour through automation, where machines, the ultimate embodiment of capital, appear as divine incarnations, but nothing is said about how, what and who will decide what is produced. In contrast, communism, as we understand it, has at its heart the transformation of labour and its relationship with nature. This is the cornerstone for recovering all the potential denied to labour by the alienated relations imposed on it by capital and, at the same time, for ending the abstraction of nature. These are the preconditions for moving from the realm of necessity to the realm of freedom, which presupposes a balanced social metabolism.

I am not proposing any magic bullet for dealing with the dangerous ecological crisis that capital will leave behind for any society emerging from its abolition. Achieving new relations of production based on collective decision-making will not mean being able to fix overnight the ecological disaster capitalism has produced. The more sober proposal I am making is that there is no need to delude ourselves with the techno-optimistic prometheanism of “fully automated luxury communism”, or resign ourselves to the hardships advocated by degrowthers. On the contrary, achieving a society based on the democratic deliberations of all workers and communities, and on planned social production through socialisation of the means of production in the hands of a minority of exploiters, can create the conditions to allow us to meet the twin objectives of (re)establishing a balanced social metabolism while fully satisfying social needs.