Is China a Great Power?

However, far from displacing the American empire, China rather seems to be duplicating Japan’s supplemental role in terms of providing the steady inflow of funds needed to sustain the US’s primary place in global capitalism.

— Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin (2014, 146)

Panitch and Gindin are wrong to assert that China will follow Japan’s path as a supplemental power supporting US dominance of the world economy. To the contrary, China in the coming years will increasingly challenge Western hegemony over the world market.

— William Jefferies (2017, 32)

China’s capitalist Great Power status defines contemporary global economics and politics. The continually escalating United States-China trade war presages real war. The US anticipates such a conflict (one it expects to lose) will most likely break out over Taiwan, although its military planning is speculative and rests on many assumptions. Vicious, albeit still proxy, wars such as the Israel-Gaza and Russia-Ukraine conflicts endure, each ceasefire simply a pause before the next round of hostilities. Racist nationalist movements in Western democracies threaten to upset the established norms of the neoliberal settlement — the formal inequality of individuals to pursue private aggrandisement in a selfish, money grabbing world. Meanwhile, the advent of a new long wave of storm and stress in the world economy manifests itself in the breakdown of globalisation and the shift to a multipolar world.

China’s Great Power status remains contested, however, by theorists seeking to downplay the significance of this shift or attribute it to causes other than capitalist competition. Michael Roberts, Zhongjin Li and David Kotz all say China remains a non-capitalist society, pointing to Communist Party of China (CPC) rule and its application of various quasi planning mechanisms. Other theorists, such as Sean Starrs (following Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin) and Sam King, accept China is a capitalist economy, but deny its challenge to US hegemony. China’s growth, for them, is strictly subordinate to the US, meaning China will never contest US global domination.

Zhongjin Li and David Kotz

In Theories of Surplus Value (TSV), Karl Marx defined a capitalist economy against three criteria. He explained that the labour production process,

only becomes a capitalist process, and money is converted into capital only: 1) if commodity production, i.e., the production of products in the form of commodities, becomes the general mode of production; 2) if the commodity (money) is exchanged against labour-power (that is, actually against labour) as a commodity, and consequently if labour is wage-labour; 3) this is the case however only when the objective conditions, that is (considering the production process as a whole), the products, confront labour as independent forces, not as the property of labour but as the property of someone else, and thus in the form of capital.

Accepting this, China can be said to have a capitalist economy if: its general mode of production produces commodities; if money is exchanged against labour power as wage labour; and if property confronts labour in the form of capital — that is money produces commodities to produce more money.

Before introducing pro-market reforms in 1978, China’s centrally planned economy had no markets, commodities, labour market, privately-owned means of production, money or meaningful prices. A central planning agency (modelled on Josef Stalin’s Soviet Union) allocated material quantities of means of production to produce various material outputs. These inputs and outputs were never sold and, therefore, had no prices; they were not commodities.

China’s definition in this period is contested, so I use the category “centrally planned economy”. Regardless, however you define China between 1950-78, it was not a capitalist market economy. Markets, insofar as they existed, were restricted to a tiny proportion of largely agricultural subsistence commodities. No means of production were exchanged on a market, and retail and farm exchanges totalled 3% of output in 1978.

Barry Naughton, a leading Western China expert, described the transition to the market from 1978 onwards as “growing out of the plan”. A minimum amount of planned output continued to be set, but surpluses above that could be sold. By the mid-1990s, the wholesale marketisation of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), as part of the very stringent conditions for China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, completed the transition to capitalism.

Larger SOEs were forced to make profits, though as many were on the brink of bankruptcy, they were allowed to retain profits for internal investment (which had profound implications later on). Smaller SOEs were privatised or went bust. About 70 million workers were fired and lost the benefits of the “iron rice bowl” (guaranteed jobs), healthcare, education, housing and pensions. By 1999, 88% of Chinese prices were set by the market, a higher proportion than for the US (See table 3.2 above). Marx’s first condition, that “the production of products in the form of commodities, becomes the general mode of production”, is clearly fulfilled.

Marx’s second condition, that “the commodity (money) is exchanged against labour-power”, was simultaneously met when the commodity economy was introduced. Li and Kotz (2020) noted that growth in the proportion of private-sector employment rose from 40% in 1998 to 82% in 2018. They concluded that “the economic base in China today is capitalist”. Nonetheless, they perversely claimed “there is no evidence that capitalists now control the [CPC] or can dictate state policy”, and that “as long as the [CPC] is not controlled by the capitalist class in China, we do not expect China to operate as an imperialist power”.

The CPC allowed capitalists to join the party in 2001. By 2018, the net worth of the 153 members of China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) and its advisory body was US$650 billion. By 2023, over 80 deputies and committee members were billionaires. The 41 billionaire NPC deputies were collectively worth $191 billion — paupers compared to the 40 advisory committee billionaires, whose combined wealth was $313 billion (Jefferies 2025).

Similarly, savings (profits) as a share of national income peaked in 2008 at 52%. Between 1978-2015, the income share of the top 10% rose from 27% to 41%, while the bottom 50% fell from 27 to 15%. In 2015, the top 1% received 14% of China’s national income, compared to 20% in the US and 10% in France (Jefferies 2025).

Leon Trotsky dryly observed, when considering the potential for state bureaucrats to restore capitalism in the Soviet Union, that their “privileges have only half their worth, if they cannot be transmitted to one’s children. But the right of testament is inseparable from the right of property” (Trotsky 1936).

From the opposite side of the political spectrum Nobel prize-winning economist Ronald Coase, who developed the notorious Coase theorem that no government intervention in the economy is ever justified, asserted during the big bang liberalisation of the Soviet Union that the abolition of Communist rule was the “sine qua non” of capitalist restoration. But China’s transition to the market made him change his mind: notwithstanding CPC rule, Coase was in no doubt of China’s capitalism (Jefferies 2025).

Marx’s third and final condition was whether the means of production confront the worker as someone else’s property — as capital. Capitalists now dominate the upper echelons of the CPC and capital accumulation accounts for the bulk of output and employment. Clearly, the claimed non-capitalist nature of China simply rests on the remaining elements of state planning or, more accurately, macroeconomic intervention into the economy and the role of SOEs.

Michael Roberts

Roberts (2015) defines China as a “non-capitalist” economy, claiming such a label is supported by an unlikely source: the World Bank. He writes that a “World Bank report admits that the capitalist mode of production still does not dominate in China.” But this is not accurate. The World Bank report, following Naughton’s logic, uncontroversially notes that China’s “economy was allowed to ‘grow out of the plan’ until the administered material planning system gradually withered” (World Bank 2013). Defining China as a non-market economy is something different, however.

The idea that capitalism did not dominate in China was included in China’s original WTO accession treaty, which imposed the most punitive accession terms on any emerging nation in the history of the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) or the WTO. Designated market economies have privileges that the WTO denies “non-market” economies. But this is not the same as defining it as non-capitalist; rather, it refers to economies that do not permit untrammelled neoliberalism and the unlimited sale of their assets to Western financiers.

The original WTO treaty agreed that, after 16 years of WTO membership, China’s status would automatically upgrade to that of a market economy. However, in an early sign of the impending trade war, Europe and the US reneged on this treaty obligation in 2017 and vetoed the change. Paradoxically, against the West’s refusal to grant such recognition, China demanded it be recognised as a market economy.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that the fiscal cost of China’s industrial policy misallocates “4.4% of GDP as of 2023”. They attribute 2% to cash subsidies, 1.5% to tax benefits, 0.5% to land subsidies and 0.4% to subsidised credit. These amounts, they claim, have “remained relatively stable over time” (Garcia-Macia, Kothari, and Yifan (2025). While 4.4% may be enough to transform a market economy into a “non-market” one, it is certainly not enough to transform capitalism into central planning.

Roberts’ (2015) claims “there was no change in the general philosophy of ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ and thus the maintenance of the dominance of the state sector”. Consequently, “China’s incredible economic success over the last 30 years was based on an economy where growth was achieved through bureaucratic state planning and government control of investment. China has raised 620 million people out of internationally defined poverty.”

He later developed these themes, asserting that “capitalists do not control the state machine, the Communist party officials do; the law of value (profit) and markets do not dominate investment, the large state sector does and that sector (and the capitalist sector) are under an obligation to meet national planning targets (at the expense of profitability, if necessary).” (Roberts 2021).

Between 1998–2005, SOEs share in industrial output fell from 50% to 30%. Meanwhile, SOEs share of employment and value-added output among large firms (not of total employment or output) listed on the Chinese stock market fell from 80% of employment in 2002 to 49% by 2019 (Garcia-Macia, Kothari, Yifan, 2025). By 2023, SOE employed only 7% of the total workforce, while just 1.3% were employed in foreign-owned units (NBS China 2024).

When SOEs were originally established, profits were small and often operated at a loss. So, firms retained after-tax profits as a cushion against bankruptcy. This concession was part of SOE marketisation, not a defence of central planning.

In 2003, major SOEs were gathered in the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC). Four years later, the State Council instructed non-financial SOEs to pay over their dividends, but the SASAC opposed these transfers, insisting that profits be retained for investment at the firm level. Strong enough to defend the existing arrangement, only 2.4% of SASAC after-tax profits were being handed over by 2019. The IMF confirmed this, estimating that “industry-level data still indicates that return on assets in 2019 were 3.5% for SOEs and 6.3% for private firms, suggesting that our findings may also be extrapolated more broadly for Chinese firms” (Garcia-Macia, Siddharth, Yifan, 2025).

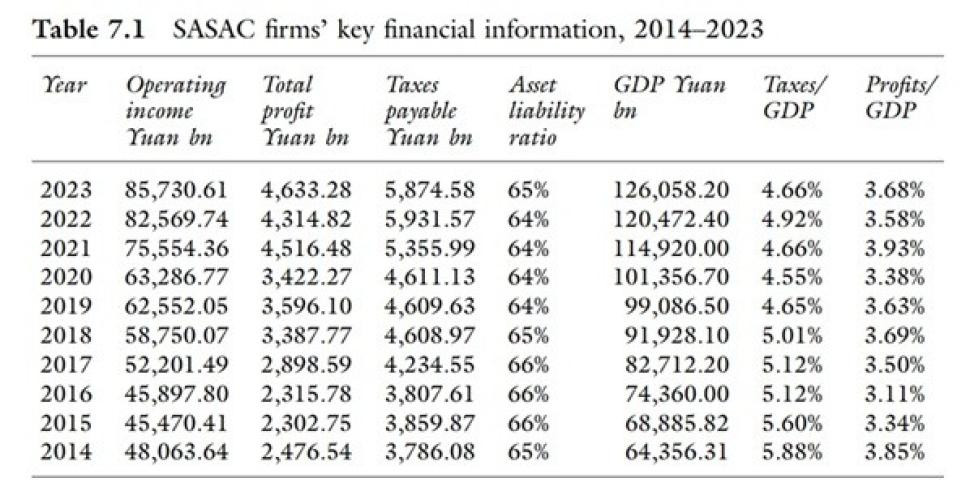

Marx noted in TSV that “the general rate of profit appears as a hazy mirage in contrast to the fixed rate of interest which, although it fluctuates in magnitude, nevertheless fluctuates in the same measure for all borrowers and therefore always confronts them as something fixed, given”. The relative constancy of SASAC ratios for assets to liabilities and taxes and profits to national income (See table 7.1 below), demonstrates that these totals are manipulated to support the SASAC’s objectives. The returns declared by the SASAC are essentially fixed at around 3.7% of GDP; they are a rate of interest. not a rate of profit.

SASAC corporations retain profits for internal priorities; they are not distributed to government shareholders in dividends. This does not indicate low profitability, low productivity or inefficiency; yet it is repeatedly treated as such.

A typical example is Ming Du’s (2023) claim that “Chinese SOEs performed poorly compared to POEs [privately-owned enterprises] both for financial performance and innovation.” Roland Rajah, lead economist at the Lowy Institute also notes: “sure, industry and tech is more productive, but inefficiency, poor allocation of funds and excess investment has still sapped productivity in aggregate” (Parikh 2025).

China’s SOEs may not pay dividends to their state owners, but their contribution to taxation is large. In 2023, SASAC taxes accounted for about 32% of total tax revenue, while individual taxes accounted for only 8.9%. Their profits are so abundant, however, that their reinvestment has cut the proportion of private investment, growing from 51% in 2010 to 64% in 2014 and 62% in 2018 before declining to 54% in 2022 (Jefferies 2025).

Meanwhile, the amount of private firms with direct state investment rose about 50-fold between 2000–19. Of the 1000 largest private firms, 65% had state investment, totalling about 15% of their capital. These large firms in turn invest in about 3.5 million smaller firms and joint ventures (Jefferies 2025).

SOEs’ relatively low distributed profits are certainly not enough to transform a capitalist economy into a centrally planned one, but they do wreak havoc with neo-classical estimates of the value of China’s fixed capital stock. The value of capital stock can be measured through two different and mutually incompatible ways.

The first method is featured in business accounts and represented in classical political economy and Marx’s circuit of capital accumulation as M-C-P-C’-M’. The capitalist advances capital (M) in the form of means of production, constant fixed capital (machinery, buildings etc), constant circulating capital (raw materials) and variable capital or wages (C) to produce (P) a more valuable commodity (C’) which is then sold for more money (M’). The balance of these costs is recorded in business accounts and needs to be discounted according to the rate of turnover.

Fixed capital depreciates over many cycles, only gradually returning to the capitalist. Circulating capital, both constant and variable, returns to the capitalist each cycle. Depending on the composition of capital and different rates of turnover of fixed and circulating capital, the amount of capital advanced by the capitalist can be very different from the annual aggregate of capital consumed in production. Advanced capital can be tied up in production, meaning while their value returns to the capitalist in the future, in amounts essentially determined by the past.

The second method values capital stock not by the amount of value tied up in production, but by the profits or services that a particular investment expects to yield. This is akin to the valuation of land derived from ground rent that Marx describes in Capital III. These estimates, common to all national statistical agencies, are described by the OECD in its handbook on national accounts, Measuring Capital:

The central economic relationship that links the income and production perspectives to each other is the net present value condition: in a functioning market, the stock value of an asset is equal to the discounted stream of future benefits that the asset is expected to yield, an insight that goes at least back to Walras (1874) and Böhm-Bawerk (1891). Benefits are understood here as the income or the value of capital services generated by the asset. (OECD 2008 p.30)

The aggregate of these discounted services (profits less costs) forms the Net Present Value (NPV) of the investment. It is determined by future, not past events, and so is not really data at all but a supposition of what may happen, an irrational measure of fictional capital. This is the valuation used in the System of National Accounts (SNA) and in business analysis for the value of investments.

It has nothing in common with the amount of capital advanced, and yet most (if not nearly all) Marxist economists treat NPV as if it were a measure of capital advanced. As the NPV is invariably much larger than the amount of capital advanced, using this figure in the denominator of rate of profit calculation means most Marxist estimates of the rate of profit are wildly inaccurate, to the point of being completely wrong (Jefferies 2022).

Roberts is one noted Marxist economist who misuses neo-classical data in exactly this way, except with one extra twist. Neo-classical data does not differentiate between modes of production and treats all human existence as a form of market economy. So, it assumes that the period of central planning also features capital, surplus value and profits. Roberts (2022) uses this data to construct a rate of return for China’s planning period between 1950-78, when there were no profits or capital in China and so no rate of profit.

Overvaluing the capital stock inherent in this data means Roberts’ profit rate estimates fall pretty continuously from 1950 on, with a brief recovery at the onset of market reforms in 1980 before slumping again after 1995 — the period of strongest capital accumulation. Roberts claims the absence of a relationship between the rate of capital accumulation and profitability means investment is not responsive to profitability. There is a far more prosaic answer, however: neo-classical capital valuations are fictional constructs, and not measures of data in any meaningful sense.

Sean Starrs

Starrs dismisses any notion that China can challenge the might of the US empire. Following Panitch and Gindin, he claims China is following a developmental path similar to Japan, as a subordinate US client.

After World War II, US Secretary of State Dean Acheson designed his crescent policy to surround the Soviet Union and Communist China, based on a crescent from Japan through to South Korea and Vietnam in the east, and another from Israel to West Germany in the west. The US enabled Japan’s accession to the GATT with privileged trade status and sponsored its recovery by converting it into a source of military materiel for US conflicts in Asia.

Japan’s 1980s challenge to the US, although much discussed at the time, was never serious. With the end of the Cold War in 1991 and the generalisation of free trade through the WTO’s foundation in 1995, Japan lost its status and entered three decades of stagnation.

Gindin and Panitch claim China is repeating Japan’s experience, and predict the moment China challenges US power (to the limited extent it can), it will wilt and fade as Japan did. This argument is misconceived.

In contrast to Japan, China’s terms for WTO entry were punitive. While there was foreign investment into Special Economic Zones (SEZs) on China’s Southeast coast and much of China’s trade was reexports of goods on behalf of Western companies, since 2008 China has sharply reoriented its economy towards domestic investment and creating “national champions” — large TNCs that can compete with Western corporations and yield higher monopoly profits, based on technological advances and high concentrations of capital.

Moreover, China’s financial industry is nationalised and the proportion of China’s domestic finance provided by foreign lending institutions is entirely marginal. After the 2008 Great Recession, China diversified its foreign assets out of US debt to yield higher returns and increase its influence, particularly over its near Asian neighbours. The 2013 $1 trillion Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is part of an even wider reaching out, enabling China to accumulate about $6 trillion in foreign assets and start the process of de-dollarisation through buying and selling in yuans.

The Forbes 2000 list of largest firms in the world is based on metrics such as sales, profits, assets and market value. The list has traced the rise of Chinese firms, which by 2024 had grown to about half the number of US firms in the top 2000. However, the Forbes list valuations need to be treated with caution.

That SOEs do not pay dividends to state shareholders decisively impacts on the valuations of these firms when using typical neo-classical NPV or Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) methods, as reflected in share prices. DCF valuations (provided by FACTSET and other data firms) share a common methodological root with NPV. Hence, valuations of Chinese SOEs, which retain profits for internal investment and growth, inevitably show lower rates of return and lower share prices — and therefore lower valuations on the Forbes 2000 list — than comparable Western companies.

Starrs (2025) argues that profit levels, not GDP, better capture the relative power of US and Chinese corporations. Starrs focuses on the Forbes 2000 list and finds that the US dominates in 13 sectors, compared with four for China (banking; construction; forestry, metals, and mining; and telecommunications) and two for Japan. The notion that China dominates world banking should be enough to set alarm bells ringing.

But, as previously mentioned, Chinese SOEs do not have high valuations because the dividends they pay (insofar as they pay them) bear no real relationship to their actual profitability, and they are not traded on international markets as they are not Western owned. The Forbes list just reflects the oversized valuations of US corporations on the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

A better measure of China’s technological advances are figures for patents in force. Patents are licensed technologies exclusive to their owner, who retain their use or charge another company for it. They enable monopoly corporations to yield excess profits.

According to the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO), China’s patents in force went from almost nil in 2004 to 4.5 million in 2024, the highest of any country. The US, on the other hand, went from 1.5 million in 2004 to 3.4 million in 2025 (Parkikh 2025). Patents are also a lagging indicator, as it takes time for inventions to be applied to production. So, this points to growing, not diminishing or subordinate, future power.

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) notes,

These new results reveal the stunning shift in research leadership over the past two decades towards large economies in the Indo-Pacific, led by China’s exceptional gains. The US led in 60 of 64 technologies in the five years from 2003 to 2007, but in the most recent five years (2019–2023) is leading in seven. China led in just three of 64 technologies in 2003–2007 but is now the lead country in 57 of 64 technologies in 2019–2023, increasing its lead from our rankings last year (2018–2022), where it was leading in 52 technologies.

We have continued to measure the risk of countries holding a monopoly in research for some critical technologies, based on the share of high-impact research output and the number of leading institutions the dominant country has. The number of technologies classified as ‘high risk’ has jumped from 14 technologies last year to 24 now. China is the lead country in every one of the technologies newly classified as high risk—putting a total of 24 of 64 technologies at high risk of a Chinese monopoly.

Similarly, Harvard’s Critical and Emerging Technologies Index observe,

Although China still trails the United States, it remains competitive and is closing the gap across several sectors. China lags in semiconductors and advanced AI due to reliance on foreign equipment, weaker early-stage private research, and shallower capital markets, but it is far closer to the United States in biotechnology and quantum, where its strengths lie in pharmaceutical production, quantum sensing, and quantum communications. Backed by economic resources, human capital, and centralized planning, China is leveraging scale to reduce dependence on imports, attract innovation within its borders, and boost industrial competitiveness.

At present the US may retain dominance due to its past, but the trend is strongly towards China. And China is not Japan: as it challenges US hegemony, US measures to contain and limit its growth will fail, and a multipolar world will emerge.

Sam King

King is another Marxist in denial about the potency of China’s development. He argues that “the question ‘is China breaking the stranglehold’ is really about whether China can break the scientific stranglehold that is held by the US in combination with the other imperialist states”. King says “China has not started to invent or bring to market fundamentally new technology that is ‘revolutionising the instruments of production’, and likely can’t”.

He does, however, hedge his bets, noting that “the increasingly rapid pace that Chinese producers are able to adopt and adapt existing technology may have begun undermining the ability of the imperialist countries to market new technology in the same monopolistic and super-profitable way that constituted imperialism’s historical model”.

King notes that much of China’s technological catch-up has been based on copying existing Western technology, thereby eroding the West’s monopolistic advantage without replacing it with a new monopoly. His mistake is to confuse this phase, which described China’s development during the period after WTO accession until about 2015, with today.

The 2015 China 2025 initiative was an industrial strategy seeking to break China’s dependence on Western technology. That policy is now bearing fruit. Chinese biotech expert Brad Loncar explains “ten years ago, China didn’t have a biotech sector to speak of. For the most part, the companies were developing generic drugs. Fast forward to today, and every big pharma is doing most of their shopping in China for novel therapies”. In 2019, annual revenues from the licensing of Chinese pharmaceuticals was little above nil; in 2024 they were $85 billion.

King claims China does not have “advanced” technology above the average, therefore it cannot achieve monopoly profits. King notes that “only new scientific developments could form the basis for China’s own technological monopolies on the world market. [But] China has not brought to market any major new technology”. He also claims that the renewable energy sector (solar, wind, electric vehicles and batteries), dominated by Chinese producers, “relate to middle level or mixed products especially electric cars, batteries, and solar panels.”

But here again he hedges his bets: in his conclusion, he writes “it is difficult to know just how threatening China’s productive forces really are to imperialism without a far more detailed technical analysis”. Actually, it is not that difficult. As I noted in 2017,

The development of indigenous Chinese technology combined with the more rapid product cycle of modern manufacturing means that in coming years China’s multinationals will increasingly compete with and replace Western TNCs in the highest value-added sectors. As they do so, the dependence on Western finances and services will simultaneously decline. At this point China will challenge the United States and Europe for the leadership of the world economy, though paradoxically, when this does happen a crucial condition for unhindered global trade, the existence of a single power able to guarantee open trade, will disappear. (Jefferies 2017)

China’s products increasingly threaten the monopoly position of Western producers. While this is a trend, and not a fixed absolute, it is a challenge that will grow in the next few years. All of the detailed technical analysis, including by Western think tanks vehemently hostile to the outcome of this process, conclude that China’s ability to compete will not lessen, but deepen and extend in the next few years.

Conclusion

China’s Great Power status is contested by Marxists from two different points of view. Firstly, that CPC rule and remnants of central planning mean China’s economy is not capitalist. Li and Kotz concede the economy is capitalist but argue that CPC rule signifies China is not a capitalist society.

These claims do not stand up to close scrutiny: the bulk of China’s output is sold at market prices, the CPC leadership is dominated by millionaires and billionaires, Chinese income inequality is higher than France, the private sector employs the vast bulk of the working class, and even the state sector produces for profit (albeit, as has been noted, this is not largely paid in dividends to state owners but retained for their own investment and expansion). Even the IMF estimates that the “misallocation” of resources stemming from the CPC’s industrial policy is only about 5% of output.

Roberts uses neo-classical capital stock valuations based on discounted aggregates of future services or NPV (and not capital advanced) to estimate a rate of profit that plunges throughout both the planning period (with no profits and capital, and therefore no rate of profit) and the present period (which has seen the strongest growth of any economy in world history). Based on this, Roberts claims China’s low profit rates proves that investment explains China’s non-capitalist nature. The more prosaic, but accurate explanation, is that Roberts’ rate of profit is based on aggregates of fictional capital developed under the rubric of NPV, and therefore wrong.

Secondly, China’s Great Power status is denied by those who concede China’s capitalist nature but claim it will never be sufficiently powerful to challenge the US Empire. Starrs compares the low declared profits of SOEs with US corporations and concludes China can never challenge the US Empire. Similarly, King claims Chinese technology will never be able to challenge the West. Both ignore the abundant evidence to the contrary.

References

Du Ming (2023). "China’s State Capitalism and World Trade Law". German Law Journal, 24, pp. 125–150 doi:10.1017/glj.2023.2

Garcia-Macia Daniel, Kothari Siddharth, and Tao Yifan (2025). Industrial Policy in China: Quantification and Impact on Misallocation WP/25/155. IMF Working Paper International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Panitch Leo and Gindin Sam (2013) "The Integration of China into Global Capitalism", International Critical Thought, 3:2, 146-158, DOI: 10.1080/21598282.2013.787248

Jefferies William (2017) "China’s Challenge to the West: Possibility and Reality". International Critical Thought, 7(1), pp. 32-50

Jefferies, W. (2022). "The US rate of profit 1964–2017 and the turnover of fixed and circulating capital". Capital & Class, 47(2), 267-289. https://doi.org/10.1177/03098168221084110 (Original work published 2023)

Jefferies William (2025). War and the World Economy; Trade, Tech and Military Conflicts in a De-globalising World. London, Palgrave McMillan.

Jurzyk Emilia and Ruane Cian (2021). Resource Misallocation Among Listed Firms in China: The Evolving Role of State-Owned Enterprises WP/21/75. IMF Working Paper International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Li Zhongjin, Kotz David M. (2020). "Is China Imperialist? Economy, State, and Insertion in the Global System". Paper written for a session of the Allied Social Sciences Association entitled “The Political Economy of China: Institutions, Policies, and Role in the Global Economy,” sponsored by the Union for Radical Political Economics, January 3–5, 2021.

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) China 2025. China Statistical Yearbook 2024. China NBS. https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2024/indexeh.htm.

Parikh T (2025) "China’s innovation paradox". Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/b44458cc-03fd-46a1-b003-b7a097419e66

Roberts Michael (2015) "China: three models of development". https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/china-paper-july-2015.pdf

Roberts, M. (2022). "China: A socialist model of Development?" Belt & Road Initiative Quarterly, 3(2), 24-45. https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/90242/ssoar-briq-2022-2-roberts-China_A_Socialist_Model_of.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y&lnkname=ssoar-briq-2022-2-roberts-China_A_Socialist_Model_of.pdf

Starrs, Sean (2025). "US Economic Decline Has Been Greatly Exaggerated: An interview with Sean Starrs". Jacobin. https://jacobin.com/2025/02/us-economic-decline-corporations-china

Trotsky, Leon. 1936 [2004]. The Revolution Betrayed. Dover Publications

World Bank (WB) 2013. China 2030; Building a Modern, Harmonious, and Creative Society. WB Development Research Center of the State Council, the People’s Republic of China. https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/China-2030-complete.pdf