Pavel Kudyukin (University Solidarity, Russia): ‘Through struggle we will obtain our rights’

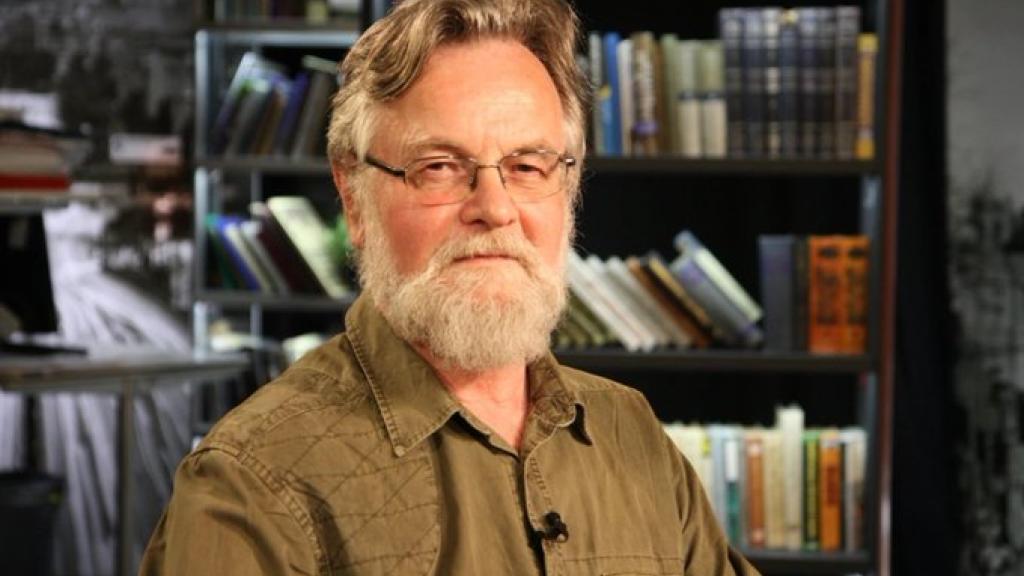

[Editor’s note: The following is an edited transcript of the speech given by Pavel Kudyukin on the panel “Repression and the threat to intellectual freedom: Russia and beyond” at the “Boris Kagarlitsky and the challenges of the left today” online conference, which was organised by the Boris Kagarlitsky International Solidarity Campaign on October 8. Kudyukin is co-chair of the University Solidarity trade union, a member of the Council of the Confederation of Labour of Russia, and was Deputy Minister of Labour of Russia (1991-1993). Transcripts and video recordings of other speeches given at the conference can be found at the campaign website freeboris.info.]

The attacks by the Russian government on academic freedom and university self-government began long before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The turning point can be considered to be 2012 when, after a short-term and superficial rise in public protest activity, authorities began to tighten the screws. The law “On Education in the Russian Federation” adopted that year limited the rights of universities to self-government, transferring to the state the approval of charters for the vast majority of the Russian universities. After this, the mass abolition of the election of vice-chancellors began, although the vice-chancellors of the two leading universities in the country, Moscow and St. Petersburg, had already begun to be appointed by presidential decree.

The destruction of self-government in universities quickly spread downwards all the way to the level of department heads and chairs of disciplines. Various methods were used. For example, the dissolution of faculties (whose deans, according to law, must be elected) and the creation of research institutes, where the law says nothing about appointing their heads. The same strategy is pursued when departments are replaced with educational programs. Another method is the appointment of “acting” officeholders without elections for a real leadership body. Here, two birds are killed with one stone: simultaneous deprivation of the right of faculties departments to elect their leaders along with increased subservience on the part of administrators (when you can be dismissed at any time without any procedural difficulty, you are unlikely to manifest “excessive” independence and criticism of the authorities).

The proportion of administrators in academic councils has increased: in many cases they are not even elected but occupy places on the council by virtue of their position. Meanwhile, while the academic council is formally the highest collegial governing body of the university, in reality it simply turns into a puppet of the administration, obediently rubber-stamping everything that is placed before it.

Fixed-term contracts for professors have an extremely unfavourable effect on the level of academic freedom. There is no equivalent of tenure in Russia and permanent employment contracts are a rare exception. It is very easy to keep a professor “on a short leash” when they must be elected to a position (by those same obedient academic councils) for a year, three or even five. If behaviour is not loyal enough (whether it be activism in an independent trade union, an open statement of opposition to government — not only the all-Russian but also the regional — or a public presentation of a scientific position in the social sciences that contradicts official assessments) it is easy to fire a teacher by simply not announcing a competition for the next term or by organising a vote against re-election.

Russian legislation also contains a bludgeon, such as the possibility of dismissing teaching staff “for committing an immoral offense” in the absence of any legal definition of what is meant by this term. There have been cases when, in accordance with this norm, professors were fired for anti-war statements, participation in street protests, and appearances in court as expert witnesses in favour of defendants in political trials that contradicted the expert opinions officially issued by the relevant university.

Such are the systemic factors in the higher education system that negatively affect academic freedom in Russia. No less, and in the current situation even more significant, are the factors associated with repressive legislation — rapidly increasing since 2012, and especially since February 2022 — and censorship on ideological grounds, which is becoming more stringent, contrary to the constitution.

Even before the start of the full-scale war, laws were passed introducing administrative and criminal liability for “insulting the feelings of believers”, “justifying Nazism”, “displaying Nazi symbols” (which now includes the state emblem of Ukraine), “equating the actions of the Soviet Union in World War II with the actions of Nazi Germany”, “justifying terrorism”, and so on. All these laws are distinguished by gross indifference to legal rigour as well as vagueness and ambiguity about the areas of application of the “offenses” and “crimes”, which creates wide scope for arbitrary law enforcement in the present context of dependence of the courts on the executive branch and the law enforcement agencies.

Special mention should be made of the development of legislation on “foreign agents”, which has evolved into broadly interpreted legislation about “persons under foreign influence”. Initially, the 2012 law was used mainly for applying moral and political pressure on undesirable NGOs, media and individual citizens. At the same time, the concept of “political activity” was interpreted extremely broadly, but to obtain the status of “foreign agent” it was at least necessary to receive foreign funding (though not always in real terms). The longer it was applied, the greater were the penalties imposed on organisations and individuals with this status and the more their rights were limited.

Finally, in the summer of 2022, the law “On The Control Of Persons Under Foreign Influence” was adopted, according to which, first, the concept of “foreign influence” was completely blurred and, second, an open employment ban was introduced on teachers and, in general, employees of educational organisations who had the misfortune of earning this “honorary title” (along with other restrictions and forms of harassment).

The war also brought in several laws directly related to military action. These are laws on “Discrediting the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation” and on so-called “fakes”, again with a wide possibility of completely arbitrary and unrestricted interpretation.

According to an (obviously incomplete) report of the human rights organisation OVD-Info, there are 23 criminal and 106 administrative known cases against teachers employed in various levels of education (from pre-school institutions to universities). Ideological pressure is growing on the entire education system, including higher education. The most striking manifestation of this in higher education was the introduction of the compulsory subject “fundamentals of Russian statehood”, the only textbook written in the “best traditions” of reactionary and conservative domestic social thought.

Even if teachers can avoid teaching this subject (although sometimes not without risk of spoiling relations with authorities and not getting the necessary amount of academic work), unfortunate students cannot avoid taking the corresponding loyalty exam. It is debatable whether “Foundations of Russian Statehood” will be effective as a means of political and ideological indoctrination (after all, we had the relevant experience of the teaching of emasculated “Marxist-Leninist” subjects in the late Soviet period). But the notorious doublethink, which we began to get rid of during Perestroika and in the post-Soviet years, will certainly be fostered again.

There is direct interference in scientific activities by both the administration and the “patriotic public”. Naturally, the most sensitive topics are those related to World War II, Stalin’s repressions, and the post-Soviet period. But the further back we go, the more news there is about interventions in such seemingly distant topics as Ancient Rus, Ivan the Terrible’s oprichnina [a policy of mass repression of Russian aristocrats] or the events of the Time of Troubles of the early 17th century. Unlike the late Soviet era, when the official ideology at least formally did not reject progressivism, the scientific picture of the world or internationalism, we are now increasingly immersed in an atmosphere of obscurantism, clerical dominance, xenophobia, rabid and aggressive nationalism and imperialism.

The pressure on natural science and technical education is somewhat less intense — after all, the authorities are smart enough to understand that they directly influence economic development and, what particularly worries authorities, military potential. However, the destruction of public and humanist education, although not so directly and not so rapidly, will have the most destructive effect on the future of the country.

For scientists and teachers in Russia, the demands for political freedoms, intellectual freedom and freedom of scientific research are not only political but professional demands. In striving for them, we repeat again and again the motto of our trade union, University Solidarity: “Through struggle we will obtain our rights!”

Freedom for Boris Kagarlitsky! Freedom for all political prisoners!