Radical objects: MaThoko’s post box and the LGBT movement in South Africa

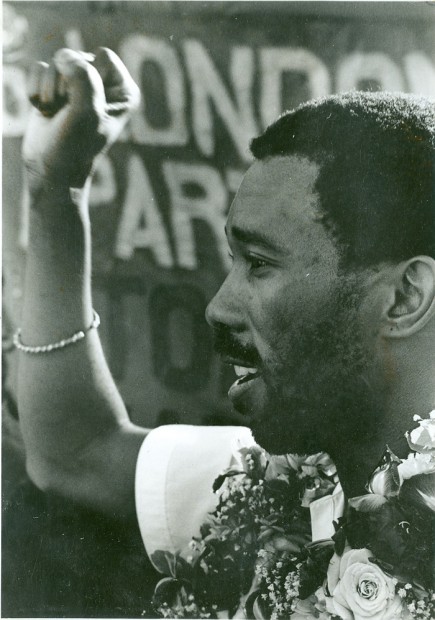

Simon Nkoli visits the non-stop picket of the South African embassy in London, July 13, 1989 (photo thought to be by Gordon Rainsford). All photos courtesy of Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action (GALA).

By John Marnell

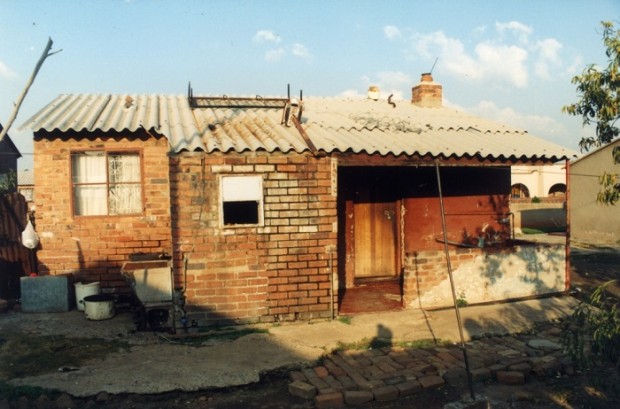

February 17, 2015 – History Workshop, posted at Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal – Sometime in the early 1980s, an unassuming house in KwaThema, a township just outside of Johannesburg, became a safe haven for the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community. Like the other houses in the township, it was small – only four rooms – and simple, matchboxes made on the cheap by the apartheid state. It belonged to Thokozile Khumalo, known affectionately as MaThoko, who for the next decade opened her home and her heart to countless young people.

MaThoko’s house was the centre of a vibrant LGBT community in KwaThema (photo by David Penney).

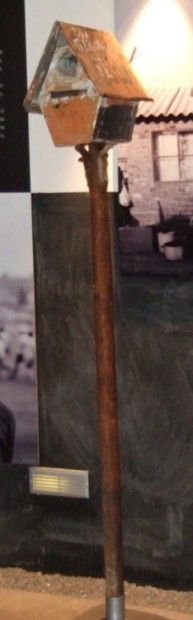

The house itself was demolished in 1997, four years after MaThoko’s death, but her old post box was saved by activists. And while this rusty, battered box may not at first seem a radical object, it did in fact play an important role in South African LGBT history. MaThoko’s house was for a time the centre of a vibrant community, and her post box served as a key communication node for the nascent LGBT movement. Letters from across the country passed through it, some related to political campaigns but many from people desperate to know they were not alone. Today the post box is on permanent loan to the Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg, where it stands as a reminder of the complex and at times difficult relationship between the anti-apartheid and LGBT struggles.

MaThoko’s post box is now on permanent loan to the Apartheid Museum.

MaThoko’s address, 33 Legodi Street, became synonymous with the Gay and Lesbian Organisation of the Witwatersrand (GLOW), the first mass black LGBT movement in South Africa. Members of the organisation would gather at her shebeen (tavern) to debate, strategise and party. But for many who knew MaThoko, her house is remembered first and foremost as a place of refuge, especially for young people disowned by their families and forced out of school. MaThoko herself was heterosexual, but she had a gay nephew, and it was concern over his safety that initially inspired her efforts to help LGBT youth. And help she did: at one point, according to Vusi Msiza, up to thirty young people were living under her roof.

Interviews with key figures in the movement reveal the fondness with which MaThoko is remembered and the important role that her house played in those early days. "Finding MaThoko coincided with my activism at school, and my mother’s nightmare dealing with the situation of me being a lesbian", recalls activist Phumi Mtetwa. "I could not sleep at home some days – either because I was in hiding from the authorities, or fighting with my mum. I would sleep at MaThoko’s. You would see everyone there: gays, lesbians, trans. There was always a blanket for you."

Phumi Mtetwa and Simon Nkoli, as representatives of the National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality, met with Nelson Mandela in February 1995.

MaThoko’s relationship with the LGBT community began at a turbulent time in South African history. The 1980s saw unprecedented levels of resistance against the apartheid state: township residents organised rent, work and school boycotts, and in August 1983 the United Democratic Front – a grassroots coalition of labour, church, women, youth and community groups – was launched.

But the decade was also characterised by widespread violence and increasing levels of state repression. The African National Congress (ANC) and other freedom movements had stepped up their campaigns of armed resistance, and violent police incursions into the townships helped to fuel tension and unrest. Violence was also directed at township residents accused of collaborating with the regime, with suspected informants attacked and sometimes executed. The groundswell of resistance was met with stricter and stricter laws. State of emergency regulations implemented by PW Botha in 1985 and again in 1986 outlawed public meetings, restricted media coverage of political events and gave police the power to hold detainees almost indefinitely. In many cases, those being held captive were tortured and killed.

For some young comrades, the liberation struggle was inseparable from the fight for sexual rights, and a new push for sexual equality began to emerge from within the anti-apartheid struggle. Before the late 1980s, the "gay lib" movement was white, male dominated and largely middle class. It also attempted to position itself as apolitical, as separate from the fight against institutionalised racism. This shifted with the imprisonment of Simon Nkoli, one of 22 activists detained in September 1984 after a protest in Sebokeng. Accused of treason, a charge that carried the death penalty, Nkoli and his comrades found themselves at the centre of one of the longest trials in South Africa’s history.

Nkoli had been involved in the 1976 Soweto uprising and over the next few years had become increasingly involved with the Congress of South African Students (an anti-apartheid student organisation established in the wake of the uprising). Although Nkoli’s sexuality had been known to some in the student movement, few of his co-accused in the treason trial were aware. In jail he refused to remain silent and took the bold step of coming out, a move that sparked heated debate among the group. Despite initial calls for Nkoli to be tried separately, the comrades eventually accepted his argument that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is as morally unjust as racism.

For many of Nkoli’s co-accused – and indeed most people in the struggle – this was their first time being confronted with the question of homosexuality. Nkoli was steadfast in his position, and his self-affirmation as a proud black gay man helped bring the issue of sexuality to the attention of the liberation movements. It was a turning point for LGBT activism, not only because it placed sexuality on the agenda but also because it explicitly linked homophobia to other forms of injustice.

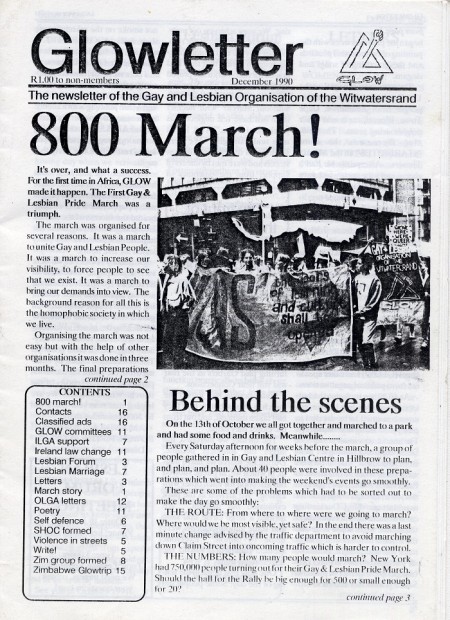

GLOW newsletter from December 1990, two months after the first pride march on the African continent.

After his release from prison in 1988, Nkoli founded a new organisation, the Gay and Lesbian Organisation of the Witwatersrand (GLOW). It was not the country’s first LGBT organisation – Nkoli himself had been a member of the overwhelmingly white Gay Association of South Africa – but it was the first to be openly aligned with the anti-apartheid struggle. Nkoli and others on the executive committee were clear about their politics, describing GLOW as a non-racist, non-sexist and non-heterosexist organisation (though whether this was the reality has been debated). Unlike its predecessors, GLOW was explicit in its position that all struggles are connected.

MaThoko’s house soon became the headquarters of the KwaThema branch of GLOW, one of the organisation’s most vibrant and active chapters. But MaThoko provided much more than a venue for meetings and parties. In an interview from April 1997 – a year before he died of AIDS-related illness – Nkoli recalls how MaThoko would provide emotional support for young LGBT people. "She did a lot of counselling for gay people", he explains. "They would come to her with problems – personal problems, organisational problems or whatever. She would also talk to other women whose children were lesbian and gay … I think that is why the KwaThema chapter was so strong." In an earlier interview, Nkoli offers a more straightforward explanation for the township’s visible LGBT community: "KwaThema gays and lesbians have a place to go – MaThoko’s." It was her active role in the movement that earned MaThoko a second nickname: MaGLOW.

That she was considered a mother figure by many is unmistakable. "MaThoko was very lovely to all of us", Mtetwa recalls. 'She was very involved in the internal issues. She used to know everything… She had a good heart. She was a poor woman who didn’t have the resources to feed us, but she had a good heart and that is what makes her stand out."

She was for many a counsellor, a support worker, an ally and, of course, a mother.

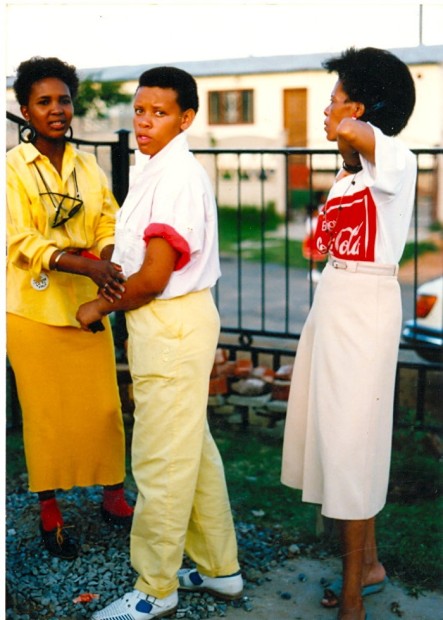

Bev Ditsie (centre) and friends celebrate her 16th birthday in Orlando, Soweto. The 1980s and 1990s saw a rise in LGBT organising and visibility in the townships.

MaThoko’s house was the site of many parties and events, and LGBT icons like Mtetwa, Nkoli and Bev Ditsie remember the raucous parties that took place there. MaThoko was, after all, a shebeen queen – a position of authority within township communities – and the freedom she offered LGBT people made them flock to her establishment. Mark Gevisser describes one such party in his book Defiant Desire:

[I]t could be any weekend afternoon township party: 1970s disco sounds scratching through the static of an over-extended hi-fi system, the orange-and-white stripe marquee in the yard, the plates of pap (stiff maize porridge), the laughter, the hostess barking genial orders from her chair. Look closer, though, and you’ll notice that the guys are dancing with each other, vogueing a home-brew version of black gay American dance styles. In a corner, two women have salvaged a quiet space from the revelry to embrace, and on the stoep a group of teenage boys are earnestly discussing outfits for the next dance show.

Similar accounts are found in other interviews and oral histories. Nkoli and Mtetwa, for instance, both mention the marquee that was erected for special occasions, as well as the many parties following GLOW meetings.

As the headquarters of the KwaThema branch, MaThoko’s house was the primary point of contact for many young people coming to terms with their sexuality or gender identity. But MaThoko’s impact extended beyond the township’s borders: her post box allowed people from across South Africa and the world to make contact with GLOW. And while we don’t know the exact number of letters, nor whether this correspondence has survived, we do know that her post box helped LGBT people to connect at a time when homosexuality was illegal and highly stigmatised.

MaThoko’s tiny house, with its battered post box standing sentinel, served as a beacon of hope for a group of people marginalised not just because of their sexuality, but also because of their race and class. Her home was a place of business and organising but also of celebration and community, and it is remembered today as a place where a movement found its feet.

A flyer advertising the 1990 pride march and its theme of "Unity in the Community!"

MaThoko died in 1993, aged 46, one year before South Africa’s first democratic election and three years before the adoption of the new constitution. She died without knowing of the groundbreaking equality clause or the many legal reforms it allowed. But her memory and spirit live on: in 2011, Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action launched MaThoko’s Books, an imprint dedicated to queer writing and storytelling. There was no hesitation when choosing a logo for the imprint – MaThoko’s post box.

The struggle in South Africa continues. Religious and political leaders continue to fan the flames of discrimination with hateful rhetoric condemning sexual diversity; the county continues to be plagued by staggering levels of rape, murder and other violent crimes motivated by homophobia and transphobia; LGBT youth continue to be kicked out of home and forced out of school.

KwaThema itself has changed greatly over the last two decades, and a number of high-profile hate crimes in the area (such as the brutal rape and murder of Eudy Simelane) has seen its reputation as a vibrant hub of queer life replaced by a much darker association. But even in the face of great hostility, activists and allies – extraordinary people just like MaThoko – refuse to remain hidden or silent.

[John Marnell is the publications and communications coordinator at Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action, South Africa. He manages MaThoko’s Books, the organisation’s imprint, and is the editor of the African Sexuality and Gender Research Series. His most recent publication, co-edited with Carien Lubbe-de Beer, is Home Affairs: Rethinking LGBT Families in Contemporary South Africa (Jacana, 2013).]