Ukraine and its language in the political imagination of the Russian empire

First published at New Politics on October 6.

On February 21, 2022, Vladimir Putin gave a long speech whose purpose was to justify the invasion of Ukraine, launched only three days later. According to the Russian president, the Ukrainian state is an illegitimate invention and the Ukrainians’ claim to a distinct identity is nothing more than the product of foreign manipulation. Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians constitute for him one and the same nation, while the policy promoting the Ukrainian language and culture would be a proof of the “genocide” against Russian speakers living on Ukrainian territory and thus justify the invasion of the country. The question of language therefore seems to play an important role in the outbreak of the Russian invasion and in the conflict between the two countries that preceded it. In order to understand Putin’s war against Ukraine and its people, one must take a close look at the place that Ukraine, its state, language, and culture occupy in the imperial and national imagination of Russians.

After the fall of the medieval state of Kievan Rus, dismantled by the Mongol invasion in the thirteenth century, much of the land that makes up present-day Ukraine returned to Poland-Lithuania, and it was not until the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that it came under Russian control. It was therefore the integration of these new territories that gave birth to the idea of a Russian nation uniting the three peoples, an idea now resurrected by Vladimir Putin. At the time, the objective of this project was to equip itself with a hegemonic group that would make it easier to exercise domination over the non-Orthodox and non-Slavic peoples. The control of Ukraine was therefore a cornerstone in the project of the Russian Empire but also and above all in the project of the Russian Nation. The assertion of a distinct Ukrainian identity was thus perceived by the Tsarist elites as an existential threat to their state.

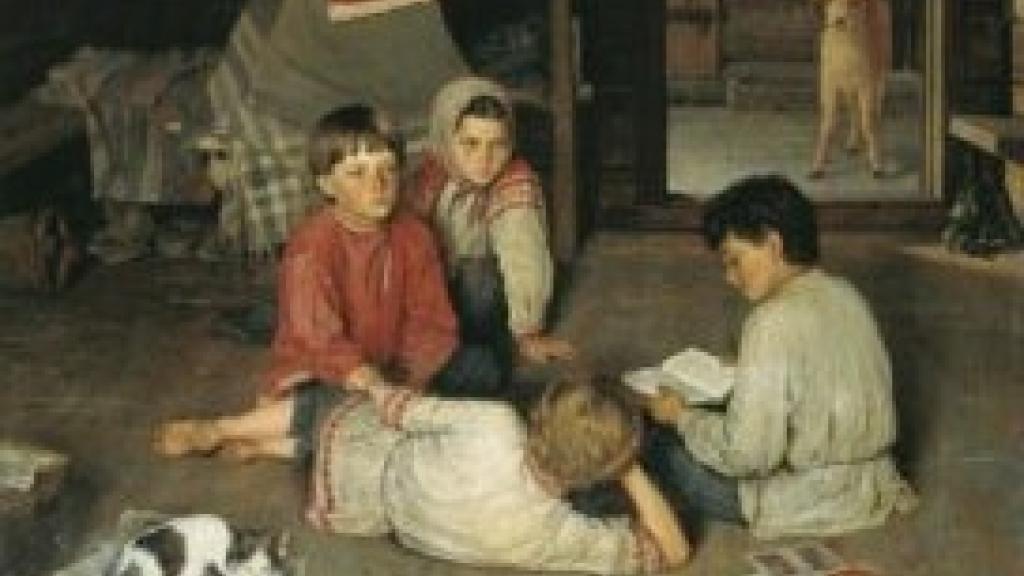

In 1863, publication and teaching in the Ukrainian language were completely banned. This policy led to a situation, probably unique in European history, of a decline in the literacy rate of the population between the middle of the eighteenth century and the end of the nineteenth century. Inequality in access to education is one of the factors that reproduce social inequalities. In the nineteenth century, Ukrainian society was thus marked by an opposition between a “backward” countryside and the Russified cities, which at the same time served as the centers of imperial domination.

Under these conditions, how has the Ukrainian language been able to survive and develop despite everything? Indeed, the infrastructures necessary for the emergence of a common national identity, such as the development of cities and communications, generalized schooling, or the development of an efficient centralized administration, remained largely underdeveloped. The Tsarist authorities, with the almost unlimited resources of their vast empire, were reluctant to invest in the costly project of truly Russifying Ukraine, integrating it into the development of the Russian nation. Rather than embark on this policy, they resorted to crude repression against the Ukrainian language. However, it was already too late: at that time, Ukrainian poets and writers, who were fascinated by Romanticism and for them the defense of their mother tongue was an important political marker; they were already conceptualizing their ethnic group as a nation. In short, the predation of the Tsarist elites, state underdevelopment and belated and incoherent pressure prevented the assimilation of Ukrainians to Russia. In general, the desire of the political elites to preserve their multi-ethnic empire while at the same time building a Slavic nation-state is one of the reasons for the the Russian state’s inherent fragility. The resistance of Ukrainians against these projects was perceived as the worst betrayal.

In 1917, the empire broke up. But a national and class awakening soon developed. The Ukrainian peasants not only claimed their right to their language, but they also demand their subjectivity, that of being political actors in their own right, of being recognized. The arrival on the political scene of this “dark masses” annoyed the urban classes, including the socialists who saw themselves as the representatives of the interests of the working class in the industrial regions of southern and eastern Ukraine. As one of the party members explained, for them, the socialists, “Ukraine as such does not exist, because it does not exist for a worker of the city.” Another wrote that the “tragedy” lies in the fact that the Bolsheviks were trying to gain an advantage over the peasantry “with the help of the Russian or Russified working class, which despises the slightest trace of the Ukrainian language and culture.” The determination with which a large number of Ukrainians fought for their sovereignty with arms in hand, however, convinced the Bolsheviks that special arrangements must be made to ensure the control of this population. So in 1923, Moscow introduced a policy to promote non-Russian languages.

With Stalin, the return in force of assimilative policies was accompanied by state violence that took extreme forms, going as far as genocidal practices. The latter also struck Ukraine, with the famine of 1932-33 that was knowingly planned by Stalin (an event called Holodomor in Ukraine). The colonial division of labor between the city and the countryside reemerged and strengthening, guaranteeing to Russian Soviet and Russified citizens privileged social positions and access to income, skills, prestige and power in the peripheral republics. After the Stalinist era, one can see the promotion of a Soviet identity that is totally confused with Russianness. Although there is no law prohibiting it, speaking Ukrainian outside the private sphere is then perceived as an expression of hostility towards the system. Speaking Russian is, on the contrary, a way to demonstrate loyalty to the existing order and respect for the hierarchy between “brotherly peoples.” Russian then became the dominant language in all areas of public life: economy, administration, culture, press, education. Thus, more and more Ukrainians abandoned their tongue, which had become a marker of cultural inferiority that hindered social mobility.

Soviet modernization and urbanization were accompanied by the strengthening of the dominant imperial culture, which perpetuated significant structural inequalities between Russian speakers and Ukrainian speakers. The post-Soviet elite has neither the will nor the means to correct these structural deficiencies, so their opportunist policies largely aimed to preserve the status quo. The law that gave Ukrainian the status of an official language was adopted under the Soviet regime in 1989 and remained in force until 2012. After 1991, the advent of capitalism and the weakness of the state did not work in favor of the Ukrainian language. Suffering from its image of inferiority, deprived of any aid from the state, little known abroad, Ukraine’s media, cultural, and artistic production couldn’t compete with the growing Russian market. Moreover, from 2004 onwards, the various clans of oligarchs in competition for power artificially fed the socio-linguistic divide in order to be able to mobilize their respective electorates around questions of identity.

In 2012, the pro-Russian political forces passed a law that was supposed to ensure the protection of minority languages, but their campaign in reality aimed solely to “defend the Russian tongue.” When President Yanukovych was impeached in 2014, the parliament tried to repeal the law. Although this decision was never ratified, Russia took this opportunity to express concern about the discrimination against Russians by what it called the “fascist junta” in Ukraine, an argument that was used to justify Russian interference in Crimea and Donbas in order, according to Moscow, to “save our compatriots.”

In 2018, the parliament adopted the law that requires that Ukrainian be used in most aspects of public life and obliges state officials and those who work in the public sphere to know and use it in their communication with customers. The Ukrainian state is therefore currently playing a major role in the construction of a common identity for the inhabitants of the country. This may seem surprising from Western Europe, in countries where this process took place more than a century ago. The situation of Ukraine, having obtained its independence only thirty years ago and remaining under Russian political and cultural domination until 2014, cannot be compared to that of nations supported by state of their own since at least the nineteenth century.

Some individuals make the conscious choice to start speaking in Ukrainian in order to distance themselves from the Putin state, which claims absolute monopoly on the Russian language and culture, considering that the use of the Russian language and belonging to its “civilizational space” are one and the same thing. Indeed, since the early 2000s, Russia has embarked on the promotion of the conception of the “Russian world” by relying on the Russian speakers of neighboring countries, who have been given a special mission. This consisted of absolute loyalty to the Russian state, which presupposed unconditional support for all Kremlin decisions. If, in the 2000s, the “Russian world” was above all a tool of soft power and international influence, beginning in 2014 it became the engine of Russian irredentism whose objective is to erase Ukraine from the world map. Presenting himself as the defender of the Russian language and culture, Vladimir Putin denies nothing less than the right of Ukrainians to exist, frequently making statements that can be qualified as incitement to genocide.

In the face of the Russian invasion and the inhuman treatment of civilians by the occupying army, the inhabitants of the country now feel themselves to be first and foremost Ukrainians, including in areas of the country where Russian remains the dominant language. In these unfavorable conditions, some of those Ukrainians who are engaged in resistance to the occupier nevertheless continue to claim the use of Russian, thus defying Putin’s exclusive privilege of imposing his power over this language spoken by millions of people who do not recognize themselves in his political project. Using the imperial language by investing it with a decolonial content could become a solution for a bilingual Ukrainian society, although it is not easy to defend today, at a time when Ukrainians struggle for their physical existence.

Hanna Perekhoda is a graduate assistant and a PhD student in history at the University of Lausanne, Switzerland. She was born and raised in Donetsk, Eastern Ukraine, and speaks both Russian and Ukrainian. This article originally appeared in Pages de Gauche, No. 185.