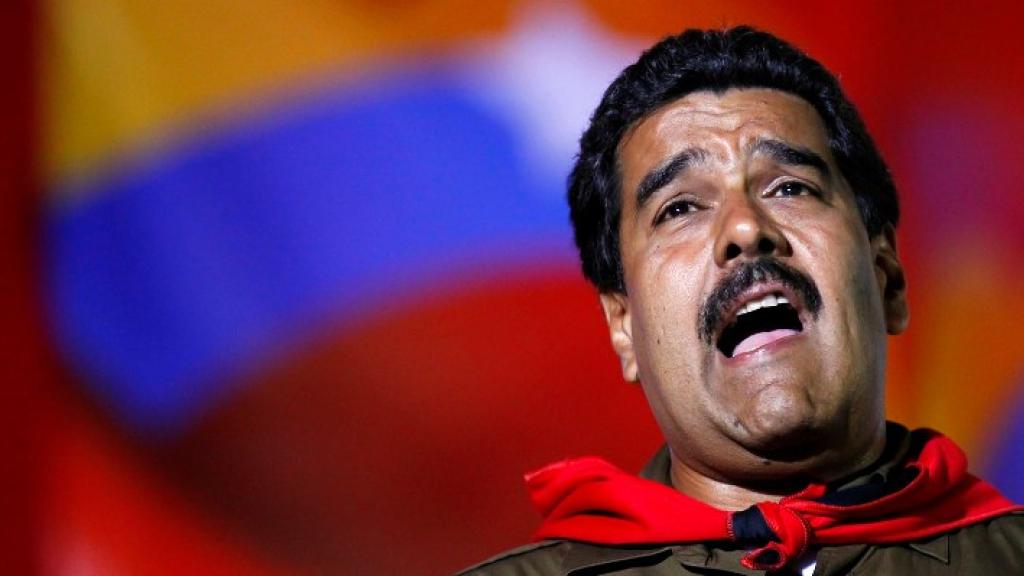

Demonising Nicolás Maduro: Fallacies and consequences

Criticism of Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro from a leftist perspective is absolutely necessary. Some of it comes from those who, to varying degrees, support his government. Emiliano Teran Mantovani and Gabriel Hetland — who recently criticised my position on Maduro — and I are in agreement on the importance of such critical analysis.

However, in spite of this common denominator, there are fundamental differences between us with regard to my insistence on the need to contextualise the errors committed by Maduro and go beyond a simplistic binary of uncritical support for Maduro versus demonisation.

These issues have far-reaching implications. The failure to objectively contextualise errors, transcend binaries and recognise shades of differences translates into an underestimation of the gravity of US sanctions and the denial of positive aspects of the Maduro government. These positions and shortcomings seriously undermine international solidarity work and anti-imperialism in general.

Centring the US war on Venezuela

Teran begins his article stating, “I want to make my position clear … these sanctions are entirely condemnable,” a position that he acknowledges is “universally shared” on the Venezuelan left and even by “some liberal scholars, intellectuals and opposition figures.” His pronouncement, however, glosses over one of my main points. It is misleading to say “I am opposed to the sanctions” and then proceed to attack government policy as if they are two separate topics.

My article explains in detail why the war on Venezuela needs to be placed at the centre of any serious analysis of the Maduro presidencies. The Washington-orchestrated war on Venezuela extends well beyond sanctions since it encompasses a broad array of regime-change and destabilisation actions. Yet Teran, like Hetland, limits his references regarding Washington machinations to the sanctions.

To make matters worse, Teran, in effect, downplays the severity of the sanctions, claiming they “do not explain the root causes” of the nation’s crisis. For Teran, the sanctions only had a “subsequent negative impact” — subsequent, that is, to the allegedly grievous errors committed by Maduro, and Chávez before him.

One example of Teran’s underestimation of the effects of the sanctions is his statement: “Ellner refers to the sanctions imposed by the Barack Obama administration in 2015, but those were limited to freezing assets and bank accounts in the US…” Teran portrays Obama’s executive order as an innocuous, symbolic measure. It hardly was.

As I noted, Obama’s order, which declared Venezuela “an unusual and extraordinary threat” to US national security, “signaled an escalation of hostility from Washington.” Even Hetland, writing a few years back, points out that Obama “pressured American and European banks to avoid business with Venezuela, starving Venezuela of needed funds.” It is not difficult to grasp why US companies operating factories in Venezuela disinvested in response to the president of their country calling Venezuela a threat to US national security.

As I previously wrote, “Obama’s executive order sent a signal to the private sector. After the order was implemented, various large U.S. firms including Ford and Kimberly Clark closed factories and pulled out of Venezuela.” They were soon followed by General Motors, Goodyear, and Kellogg’s, as well as Japanese firm Bridgestone.

Indeed, even before Donald Trump assumed the presidency in 2017, a de facto financial embargo had already been imposed on Venezuela. Opposition spokesperson and economist Francisco Rodríguez noted back then that “the financial markets are closed to Venezuela.”

Teran’s minimisation of the effects of the war on Venezuela reinforces and legitimises the opposition’s narrative, which ridicules Maduro’s assertion that Washington’s actions are responsible for Venezuela’s dire economic situation. Moisés Naím, one of the architects of Venezuela’s neoliberal policies of the 1990s, for example, writes: “Blaming the CIA … or dark international forces, as Maduro and his allies customarily do, has become fodder for parodies flooding YouTube.”

Similarly, Teran says: “Followers and supporters of Maduro’s government seem to always prefer to look for external scapegoats.” In my article, I cite specific examples of the abundant, well-documented literature that substantiates Maduro’s allegations regarding generously financed “dark international forces.”

In his effort to discard the relevance of the war on Venezuela, Teran even suggests that explanations of Maduro’s implementation of neoliberal policies on the basis of US imperialist aggression are akin to those put forward by those who seek to justify Netanyahu’s genocide against Palestinians on the basis of Hamas’ October 7 attack.

But it should seem pretty obvious to anyone on the left that drawing an equivalence between US imperialism and the October 7 attack is somewhat far fetched, and that placing Maduro’s economic policies in the same category as Netanyahu’s genocide is even more outrageous.

Neither praise nor condemnation

Turning to the second area of contention, serious analysis of Maduro needs to avoid absolutes with regard to either praise or condemnation of his government. Failing to grasp the complexity of how a progressive government is forced to navigate a situation imposed by the world’s most powerful nation located in the same hemisphere, leads to simplistic conclusions that often align with those of the political right.

Teran accuses me of being one-sided. He claims my “arguments lack nuance” and that I fail to “avoid simplistic binaries.” In doing so, he overlooks the criticisms of Maduro that I presented in my article and have analysed in greater detail in other publications.

Accusing me of one-sidedness mirrors what others who vilify Maduro do when they brand supporters of progressive Latin American governments as “campist,” or upholding “a Manichaean outlook” – a phrase used by Teran. Both terms are reminiscent of McCarthyism, with its attack on the entire left for being crypto-Communists or fellow travelers.

By failing to recognise the validity of the position of critical support for Maduro, Teran shows he is on board with a polarisation of Venezuelan politics that leaves gradations out of the picture. For example, Teran (like Hetland) unfairly accuses me of justifying repression by omission, adding that after the July 28, 2024 presidential elections, “sectors of the international left” ended up “legitimising the brutal repression.”

He neglects to mention that I suggested the evidence of significant right-wing and foreign involvement in the post-July 28 violent protests does not rule out the possible use of excessive force by the Venezuelan state, as the two are not “mutually exclusive”.

Which left?

Teran ends by asking why, instead of providing critical support to Maduro, does the international left not “dedicate their energy, resources, support and advocacy to strengthening a left-wing opposition [in Venezuela] that might someday challenge for political power?” The question, however, is somewhat ambiguous.

If Teran is referring to what political scientists call “a loyal opposition” — one that recognises the challenges facing Maduro, does not hesitate to support him in his denunciation of imperialist aggression, and avoids equating him with the Venezuelan far right — then such a proposition sounds reasonable.

But the bulk of the Venezuelan left opposition hardly fits this description. It demonises Maduro, just as Teran and Hetland do, and the actions of many of these leftists play into the hands of the political right.

If Maduro is brought down, the far right — headed by María Corina Machado, who says she wants to see Maduro and his family behind bars — will undoubtedly dominate the new regime, with Washington’s blessing. If this were to happen, the most likely scenario would be the kind of brutal repression that has historically followed the downfall of progressive governments, from Indonesia in 1967 to Chile in 1973. The anti-Maduro left is simply too weak to shape the course of such events.

It is troubling, for instance, that the Communist Party of Venezuela (PCV), in spite of its glorious history dating back to its founding in 1931, endorsed the presidential candidacy of Enrique Márquez in last year’s election. Márquez was a prominent leader of one of the main parties that actively promoted destabilisation and regime change in the protracted street protests against Maduro in 2014 and 2017, and wholeheartedly supported the right-wing parallel government of Juan Guaidó after 2019.

International solidarity

Two key implications of the debate over the demonisation of Maduro hold particular significance for the solidarity movement. First, vilifying Maduro discourages solidarity work. I have reached this conclusion based on my experience giving numerous talks sponsored by solidarity groups in cities throughout the US and Canada since 2018.

Solidarity activists have made clear to me that a fairly favourable view of the Maduro government — specific criticisms notwithstanding — is a motivating force for them. By contrast, those who despise a government are unlikely to work with the same degree of enthusiasm in opposition to US interventionism.

In this respect, the solidarity movement differs from the anti-war movement, which tends to be less focused on the domestic politics of the nations of the South and more concerned with military spending and the death of US soldiers, in addition to the devastation caused by US armed intervention.

Secondly, an analysis that contextualises government errors and the erosion of democratic norms leads to a fundamental conclusion. The extent to which the war on Venezuela is relaxed directly correlates with the potential to deepen democracy, invigorate social movements and expand the government’s room for maneuver, thereby increasing the likelihood of overcoming errors.

History, after all, teaches us that war and democracy are inherently incompatible. In their vilification of the Maduro government, Hetland and Teran overlook this simple truth.