Imperialism: Now we have some numbers

Of the world’s total of more than 200 countries, only about 20 are usually considered to be highly “developed”. The roll-call of the world’s rich, powerful states has undergone startlingly few changes over the past century, and claims that poorer countries and populations are now “closing the gap” are no more than ambiguously correct.1

In the view of Marxists, the rift that divides the world is a direct result of imperialism. As a system, imperialism operates in a multitude of ways, but its core is always material and economic. This essence lies in the persistent draining of wealth from subject portions of the globe, either through violent expropriation or, more subtly, through installing mechanisms that operate without fanfare and of which the victims are often oblivious. While these flows of wealth can be traced in national statistics — or in the case of unequal trading exchange, have been demonstrated by Marxist scholarship — a major weakness until recently in the left-wing critique of imperialism has been the imperfect quantification of overall transfers. What are the dimensions of these transfers, and how significant are they for understanding the sharply different economic evolution of rich and poor countries?

Now we have some serious numbers. Three articles in recent years have provided particularly rich insights. The first that will be considered in the present text was published in April 2024, and bears the title “Has the US exorbitant privilege become a rich world privilege? Rates of return and foreign assets from a global perspective, 1970–2022”.2 The work of Gastón Nievas and Alice Sodano of the World Inequality Laboratory at the Paris School of Economics, the article analyses what its authors term the “excess yield” of profits, interest and rents (in the terminology of the International Monetary Fund, “net primary credit income”) derived by the richest countries from the rest of the world.

An earlier article, dating from 2021 and co-authored by Guglielmo Carchedi of the University of Amsterdam and independent British researcher Michael Roberts, is entitled “The Economics of Modern Imperialism”.3 As well as providing an overview of the processes of contemporary imperialism, this article aims to quantify the flow of surplus value from the major “dominated countries” to the imperialist bloc in the years between 1945 and 2019, with a particular focus on the phenomenon of unequal trading exchange. In the third text, published online in April 2024 and entitled “Further Thoughts on the Economics of Imperialism”,4 Roberts brings the analysis forward to include data for the period through 2022.

Together, the results reached by these two sets of authors show that the imperialist bloc — roughly, the so-called G7 powers plus less influential but still wealthy states — gains close to 3% of its GDP each year from exploiting the Global South. The net transfer of wealth from poor countries to rich has gouged a huge chunk — far greater than aid donations — out of the ability of the South to improve the well-being of its citizens. Recent years, moreover, have shown a pronounced trend for the scale of this plunder to increase.

The above findings have striking geopolitical implications. They show that the value of economic growth in the “core” countries of imperialism in recent times has been substantially less than the sums extracted by them from the dominated periphery of global capitalism. While the amounts flowing annually from the periphery to the heartlands of the system have corresponded to some 3% of imperialist economic output, GDP growth in the G7 economies during 2013–2023 averaged only 1.8%.5 All that saves the imperialist countries from more or less permanent economic depression and decline, it follows, is constant infusions of poor-country wealth. The ruthlessness of imperialism in policing the planet thus ceases to be any mystery; for the imperialists, an aggressive hegemonism is a condition of their survival.

The studies to be examined here also settle a crucially important question for the world left: they show, definitively, the position and role of the BRICS states within the structures of the global economy. Implicitly demonstrated by one set of authors, and stated forthrightly by the other, is the conclusion that the BRICS countries, including China and Russia, are not part of the imperialist bloc.

Economic imperialism: The admitted mechanisms

Bourgeois economic science acknowledges a net flow of wealth from poor countries to rich, seen as occurring principally through the transfer of profits, interest and rents. Lesser mechanisms include international currency seigniorage — briefly, the ability of the world’s richest and most powerful states to issue fiat currency and have it accepted in exchange for goods of real value — and also, potentially, changes in the valuation of assets and shifts in currency exchange rates. Capitalist ideologues are at pains to justify this flow of riches, arguing typically that its various streams provide owners of capital in wealthy countries with a fair, necessary compensation for the risks involved in cross-border investment.6

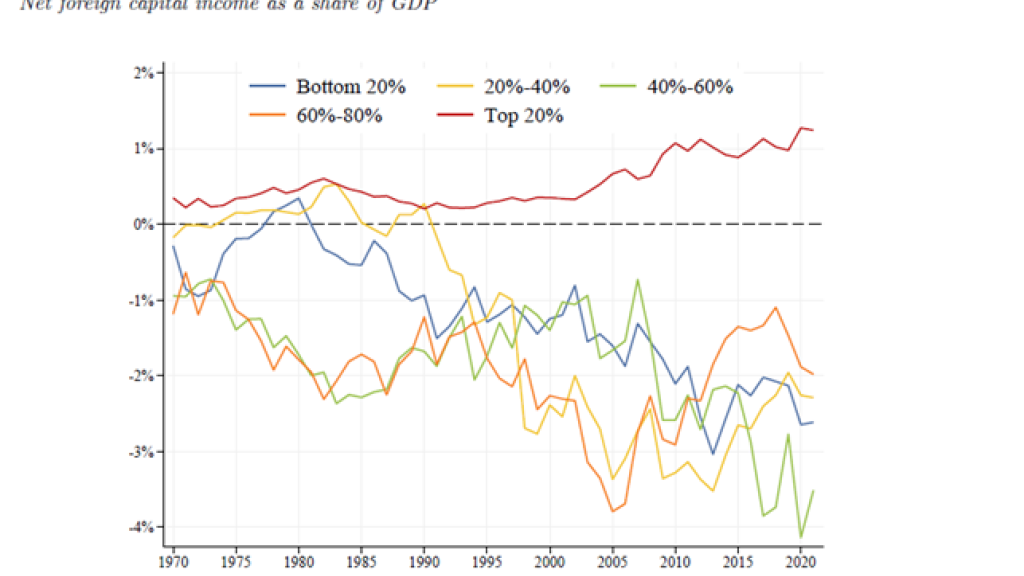

The present text will begin by addressing the key international wealth transfers that the mainstream economic profession admits exist, referring principally to the research by Nievas and Sodano. These scholars in their article make no explicit use of the concept of imperialism, instead dividing the world’s countries into quintiles by GDP per capita, on a population-weighted basis. Throughout the period since 2000, Nievas and Sodano calculate, the “top 20 per cent” of countries have received positive annual net transfers of profits, interest and rent on average totalling “excess yield” of about 1% of these countries’ GDP, rising to about 1.2% during the past decade.

The study by Nievas and Sodano has the virtue of employing an exceptionally wide data-set, covering almost all of the world’s independent states. A shortcoming of these researchers’ methodology, however, is the fact that their top quintile of countries includes states such as Chile, Croatia, Poland, Portugal, Romania and Uruguay that are distinctly subordinate compared to the real centres of global capitalism; indeed, these not-especially-rich countries are shown to benefit little, if at all, from the net global flow of wealth. However, Nievas and Sodano also cite a “top 10 per cent” category that in effect represents an expansion of the G7 group of countries, minus Italy but including states such as Australia, Switzerland and Norway. For these exceptionally well-off countries, the annual cross-border stream of excess yields — that is, the gap between returns on foreign assets and the outflow of funds to meet foreign liabilities — is positive in the degree of about 2% of GDP. The most exorbitant privilege has been enjoyed by the US, for which excess yields since 2000 have generally been in the range of 2–3 per cent, with an increasing trend.

The richest countries, Nievas and Sodano explain, have prospered by acting as the “bankers of the world”. These wealthy states — and supremely, the US and Britain — provide secure if low-yield havens for the excess savings of the governments, corporations and well-off citizens of poorer nations. Taking the cheap liquidity provided by the world’s poor, the rich-country financial elites then go on to invest these inflows in more profitable ventures, many of them in the Global South.

In recent years, the rates of return on assets held abroad have tended to decline for both rich and poor countries alike, even while the actual volume of these assets has continued growing exponentially.7 For liabilities owed externally, the picture is different. As a result of the central position of the rich countries in the international monetary and financial system, Nievas and Sodano explain, the cost of maintaining these liabilities has decreased for the 20% of richest countries, but not for the rest of the world. For the wealthy countries, credit is cheap and growing cheaper, with the following results:

This big net transfer of resources allows the richest countries to incur bigger trade deficits without the need to indebt themselves ... Moreover, it forces the bottom 80% of the world to record trade surpluses to be able to finance such a transfer. If they fail to do so, then they . . . need to compensate by acquiring more debt, which reinforces the dynamics.

Even countries of the Global South that have larger foreign assets than liabilities (for example, various oil-exporting states) can finish up losing if they have to pay out more on their liabilities than they make on their assets. This situation is not the result of self-acting economic mechanisms, but as Nievas and Sodano point out, has been contrived and maintained by those it favours: “The rich privilege comes from an institutional design, contrary to the belief of being a market outcome”.

The states of the Global South that have finished up marginalised and exploited by the world financial system include the five large “middle income” countries of the original BRICS bloc: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. Since 2007, the net flows of primary credit income for these countries have been negative, corresponding to annual GDP losses of 2–3 per cent. Nievas and Sodano remark of Brazil, for example, that it “would need to either reduce its liabilities by more than half or more than double its assets before generating net positive capital income.”

This shared dilemma of the BRICS countries has come about despite their economies displaying sharply divergent features. India has suffered from consistent trade deficits since the 1990s, while Brazil and South Africa have recorded surpluses throughout most of this century. China with its huge trade in manufactured goods, and Russia with its earnings from exports of oil, gas, metals and grain, have become major creditor countries. In each case, however, excess yields have been negative, with the income received from low-yielding foreign assets failing to offset the larger sums dispatched abroad.

Unequal exchange

Carchedi and Roberts in their 2021 article address “some key new economic and financial traits of modern imperialism”, and in particular, “the relations between the imperialist and the dominated countries through the prism of Marx’s labour theory of value”. Compared to Nievas and Sodano, these researchers employ a smaller data-set, limited essentially to the G20 group of relatively large world economies. The G20 encompasses the most powerful imperialist states — the G7 countries, plus Australia — and the “top tier” countries of the Global South, including the five original BRICS nations. On the basis of the transfers of value between these two poles of the G20, Carchedi and Roberts demonstrate the exploitative relations between the imperialist core of the capitalist world-system and the global periphery.

Limited to the G20 states, the quantifications arrived at by Carchedi and Roberts lack the worldwide scope of the accounting of “excess yield” performed by Nievas and Sodano. The particular value of the work by Carchedi and Roberts lies in something that Nievas and Sodano do not attempt: the use of a distinctively Marxist concept, unequal trading exchange, to quantify an additional massive flow of wealth from poor countries to rich.

If we begin with the transfers acknowledged by mainstream capitalist economics, Carchedi and Roberts note that the G7 countries run a huge and persistent net primary income surplus, with the totals having risen steeply since about 2000. By contrast, the “dominated countries” that are members of the G20 but not of the G7 pay out far more than they receive. The “leakage” from these latter countries is put at close to US$250 billion a year, on a worsening trend. Meanwhile, Roberts observes in his 2024 article, the top five imperialist economies in recent years have “obtained a staggering 1.7 per cent of their annual GDP from such net inflows.” The biggest gainers “have been Japan with its huge foreign asset holdings and the UK, the rentier centre of financial circuitry.” In contrast, the BRICS economies have “lost 1.2 per cent of their GDP a year in net outflows”.

To the net flow to the imperialist “centre” of profits, interest and rents, Marxist science adds the massive transfer of wealth to the rich world through the mechanisms of trade between countries on different levels of technological development. This unequal trading exchange is almost universally ignored by bourgeois economists (or dismissed as a communist fiction), essentially because it rests on Karl Marx’s labour theory of value. Acknowledging it would require accepting that capitalist profits originate from the expropriation of value created by workers.

Unequal exchange is explored by Carchedi and Roberts in complex detail, but for present purposes it is enough to recall that in a capitalist economy, as Marx demonstrated, the sole source of surplus value (and thus of corporate profits, interest and rents) is uncompensated human labour. Superior levels of technology in advanced economies allow much higher labour productivity than is typical of the Global South, meaning that trade between South and North implies the exchange by the South of goods embodying relatively large amounts of socially necessary labour (and accordingly, value) for goods created using much less. Though obscured in the process of international trade (where goods are exchanged on what appears superficially to be an equal value-for-value basis), the actual flow of value shows up in the much greater accumulation of wealth in the countries of the North.

From their research, Carchedi and Roberts conclude that since World War II, the G7 countries have each year gained about 1% of their GDP as surplus value from trade with the non-imperialist countries now in the G20 (the total transferred to the G7 countries from the whole of the Global South is of course greater, since most countries of the South are not in the G20). The non-imperialist G20 countries have meanwhile lost about 1% of their GDP through this mechanism. In recent years both of the above figures (of about 1%) have tended to increase. When the losses to the South from primary income flows are added in, and if allowance is also made for the effects of shifts in exchange rates and asset valuations, it emerges that even the larger and more robust “developing” economies typically suffer annual losses of 2-3 per cent from their commercial and financial interactions with the North.

The gains of the imperialist bloc, and especially of the main financial powers within it, are correspondingly enormous. When the figure of 1% of GDP from unequal exchange is added to the data for net primary credit income calculated by Nievas and Sodano for the years between 2010 and 2022, the richest 10% of the world’s countries are seen to benefit by more than 3% of their GDP. For the US, the figure is no less than 3.6%. The success of the US economy in continuing to function despite big trade deficits and huge levels of debt, and the ability of British capitalism to survive despite the evisceration of its advanced industry, both begin to seem less mysterious.

It is worth noting that for the second income decile defined by Nievas and Sodano (that includes countries such as Chile, Greece, Italy, Poland, Portugal and South Korea), the average for excess yields comes in negative, at minus 1.54% of GDP. It is unlikely that gains from unequal exchange, if they exist, make up this deficit for any of the states concerned.

The figures cited above are profoundly important for the world left, as it seeks to understand the role within world capitalism of the larger and more developed economies of the Global South. Roberts in his 2024 article states bluntly:

Over the last 50 years . . . the imperialist bloc is unchanged and increasing its extraction of wealth income from the rest — and that includes the likes of China, India, Brazil and Russia. In that sense, these BRICS countries cannot be considered even sub-imperialist, let alone imperialist.

China and Russia

The outflow of capital from China in the form of profits, interest and rents is calculated by Nievas and Sodano to have been close to 2% of the country’s GDP each year between 2005–22. According to these researchers, the negative numbers are explained in large measure by equity liabilities owed by China and by debts that have been substantially more expensive than the world average; for any risks involved in entering the huge and lucrative Chinese market, Western interests have compensated themselves well. Meanwhile, average labour productivity in China has remained a fraction of that in leading Western countries, with Carchedi and Roberts putting the figure attained in the last few years at only about 25% of that in the United States. This points to a vast flood of wealth from China to the advanced West through unequal trading exchange.

In all, Carchedi and Roberts speak of “a clear transfer of surplus value from China to the [imperialist] bloc, averaging 5–10 per cent of China’s GDP since the 1990s”. During these decades, the imperialist countries were gaining around 1% of their GDP in uncompensated value through their trade with China, this figure reaching about 1.5% in the years from 2014 to 2019 — approaching the growth of the imperialist economies during the latter period.

In the decades since 1990, the Chinese economy has of course expanded at an exceptionally rapid pace. China has become a creditor country on a huge scale, and over many years has been largely responsible for financing the budget deficits of the US. None of this, however, mitigates the scope of the imperialist plunder to which China has been subject. Carchedi and Roberts calculate that China’s negative unequal exchange with the imperialist bloc has averaged more than 60% of its annual exports to the countries concerned. This mammoth cost of “reform and opening up” is one that Chinese leaders have clearly considered their country obliged to suffer as part of the cost of obtaining the technical and commercial expertise needed for modernisation.

At the same time, Carchedi and Roberts note a sharp contrast between the outcomes for the imperialist countries of their dealings with China, and the returns for China from its trade with other states of the Global South. China, these scholars remark, has “gained little or nothing in surplus value” from its trade with the latter countries. Taken with the figures cited earlier, this leads Carchedi and Roberts to conclude: “China is not an imperialist country by our definition; on the contrary, it clearly fits into the dominated bloc”.

For Russia, the costs of opening up to the imperialist bloc have been still more burdensome than for China, and the ultimate results much less favourable. Selling minimally processed raw materials into world markets, Russia stowed foreign earnings worth hundreds of billions of US dollars in low-yielding US treasury bonds. The small earnings on these bonds went nowhere near making up for the sums departing from Russia as remitted profits, interest payments and rents. After admitting Western firms into its economy, Russia, as related by Nievas and Sodano, finished up incurring “enormous losses due to foreign direct investment liabilities”. Between 2010–22, according to these researchers, Russia’s annual losses in net primary income were among the worst for the BRICS nations, averaging close to 4% of GDP. Carchedi and Roberts in their study of unequal exchange do not provide specific figures for losses to Russia via this mechanism. But with labour productivity in Russia probably no more than a third of the level in the US,8 and with the value of Russian exports in 2021 almost 30% of GDP,9 the additional flow of surplus value out of the country via unequal exchange has clearly been massive.

Identifying imperialism: Implications for the left

Even without the research reviewed in the present article, there is a mountain of evidence that China and Russia should not be categorised as imperialist countries, and certainly not in the terms that Marxists have traditionally employed.10 To cite just one statistic, in 2021 the BRICS group to which China and Russia belong accounted for less than 1% of the world’s total stock of foreign direct investment11 — hardly a sign these countries are taking part in the imperialist division of the globe. The numerical data that Nievas, Sodano, Carchedi and Roberts have put forward should be regarded as the “clincher”.

What does this indicate for the practice of the left, particularly with regard to international conflicts involving China and Russia? In struggles between imperialist and non-imperialist states, Marxists are not neutral, even if the main protagonists on both sides are capitalist classes (whether the Chinese state should be regarded as capitalist is a complex question on which the Western left has no common position; for present purposes, the crucial point is that China is not imperialist). Historically, members of the left have recognised that the ruling classes of imperialist countries are incomparably more dangerous enemies of the global proletariat than the relatively weak bourgeoisies of the developing world. In the fight against the main capitalist enemy, working-class forces are, in general, obliged to give limited, critical support to bourgeois-nationalist formations in the Global South that engage in anti-imperialist struggle.

This also applies when the direct combatants in imperialist wars do not, technically, include the imperialists themselves. Global capital has repeatedly instigated “proxy wars”, priming and arming developing-world states or nationalities to engage in conflicts that ultimately serve only imperialist interests. One instance is the prodigiously bloody 1980–1988 conflict between Iran and Iraq. Whether or not the US actively encouraged Saddam Hussein’s regime to launch its invasion of Iran, as is widely alleged, the US, Britain, France and Italy certainly provided Iraq with billions of dollars in funding for the war, as well as satellite intelligence and generous supplies of weapons. In the case of the Russia-Ukraine war, NATO powers have ratcheted up their pressures and menaces against Russia for over close to thirty years, eventually training and equipping large, battle-ready Ukrainian armed forces directed against Russia. In wars such as these, the question of which side struck first — international capital’s friends and agents, or the targets of its unremitting hostility — should at most be a secondary question for Marxists, who look above all for the social fuel of conflicts, not for the spark that sets them off.

While Russia is unquestionably under attack by global capital, even back-handed solidarity with the Putin regime is something that comes hard to many sections of the world left. Those who find the thought of taking such a position distressing, however, might reflect that to stand on the same side of the lines with imperialism is to locate oneself in a still more uncomfortable, compromising place. The occasions when imperialist foreign policy has any progressive vector are exceedingly rare, and generally fleeting. The Ukraine war is not one of those occasions, and any members of the left who suppose it is, risk being “found out” by history as imperialism escalates its aggressions further. To cite one example, the argument that the Ukraine conflict is anything but a proxy war on Russia has become inane now that NATO-supplied weapons and satellite intelligence are being used in an invasion of Russian territory.

In the final instance, of course, the solidarity that the left owes to developing-world capitalists who engage in struggle against imperialism is solidarity with the struggle, and not with the capitalists. When we stand alongside Russia’s capitalist government, we do so in order to see it deposed by the country’s working class on the first day this becomes possible. Our support for that government is, to borrow Vladimir Lenin’s remark in “Left-Wing” Communism, “support . . . in the same way as the rope supports a hanging man”.

The Marxist left, meanwhile, has its own, distinct methods of combating imperialist aggression based in proletarian internationalism. The potential for solidarity between Russian and Ukrainian workers is especially great precisely because this is a proxy war, being fought, in the final analysis, for ends that are not Ukraine’s own. With every military recruitment vehicle burned by enraged Ukrainian workers, a blow is struck against the savageries practised by the whole gang of capitalists — the imperialists, the oppressively anti-worker Ukrainian authorities, and ultimately, the Putin regime in Russia.

For the left, clarity on where the dividing line falls between imperialism and its victims is indispensable. Through the texts examined in this article, the world’s progressive forces have some numbers to orient themselves, and to proceed on a correct heading.

- 1

The “catch-up”, it is clear, has occurred mainly in China. The World Bank’s 2024 World Development Report (p. 36) notes that relative to the United States, the income per capita of middle-income countries “has been stagnant for decades”. If China is excluded, the gap with the US increased substantially between 2014 and 2022 (https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2024). Between 2019 and 2022, meanwhile, the number of people around the globe living in extreme poverty rose by 23 million (https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview).

- 2

https://wid.world/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/WorldInequalityLab_WP2024_14_Has-the-US-exorbitant-privilege-become-a-rich-world-privilege_Final.pdf

- 3

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357210363_The_Economics_of_Modern_Imperialism

- 4

https://links.org.au/michael-roberts-further-thoughts-economics-imperialism

- 5

https://www.worldeconomics.com/Regions/G7/

- 6

Nievas and Sodano provide detailed refutations of the chief rationalisations advanced for imperialist exploitation.

- 7

In their introduction, Nievas and Sodano note: “Gross foreign assets and liabilities have become larger almost everywhere, but particularly in rich countries, and foreign wealth has reached around 2 times the size of the global GDP, or a fifth of the global wealth. The unequal distribution of this external wealth, with the top 20% richest countries capturing more than 90% of total foreign wealth, poses constraints on the poorest countries”.

- 8

See: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Hourly-labor-productivity-in-Russia-and-other-countries-compared-to-the-US-level-in_fig1_343267959

- 9

https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/RUS

- 10

https://links.org.au/myth-russian-imperialism-defence-lenins-analyses

- 11

https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/diae2023d1_en.pdf