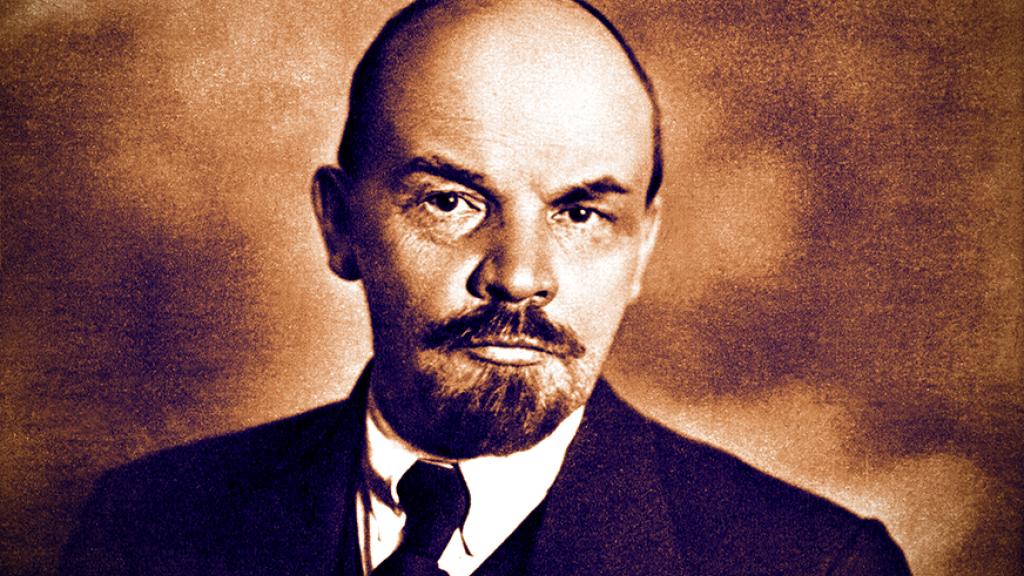

Lenin’s contributions to political economy

Vladimir Lenin made many valuable contributions to Marxist political economy.1 His 1899 book, The Development of Capitalism in Russia, is a model of Karl Marx’s Capital for the 20th century and an exemplar of the class approach to political economy. His writings on imperialism, including his book, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, innovatively develop some of the themes from Marx’s general law of accumulation presented in Chapter 25 of Capital Vol 1. They demonstrate the power of Marxist political economy when conducted at the global scale, as opposed to local and national scales. Lenin remained wedded to the labour theory of value, the theory of surplus value and the doctrine of class struggle. An avowed internationalist, he was deeply sensitive to the specificities of the Global South.

There is good political economy and bad political economy. The current political economy discourse on Lenin suffers from a series of problems. It offers many problematic revisionist claims, including denial of, or underemphasis on, a series of facts/processes in capitalist society, such as: the tendency towards class differentiation, the impoverishment of workers, the inevitability of periodic crises, the significance of value relations, the importance of capitalist imperialism as a concept, limits to the power of capitalism and its state to solve problems caused by capitalism, the priority of class relations over spatial/geographical relations, and so on. Lenin’s political economy responds to these problems and advances a Marxist alternative on many themes.

My commentary is divided into three parts: general comments on Lenin’s view of political economy as a field of knowledge; his substantive claims on the political economy of capitalism; and a comradely critique.

General comments

What is political economy and what is its importance?

Following Marx’s economic doctrine, Lenin said political economy is a science of society that studies not production as such but the social relations of production and distribution as they change over time. “[P]olitical economy is the science of the historically developing systems of social production [and distribution]” (Lenin, 1898). “[T]he most important problems of contemporary social life are intimately bound up with problems of economic science.”

Political economy must examine “the connection between, and interdependence of, the various aspects of the process taking place in all spheres of the social economy” (Lenin, 1899a). In particular, political economy must deal with the “question [of]…the relation of economics to politics” (Lenin, 1916a). A 1911 plan for a lecture on fundamentals of political economy (Lenin, 1911) includes the following topics: “The essence of the capitalist mode of production as compared with the other modes of production historically preceding it”; “Similarity in the existence of class oppression and distinction in the forms and conditions of the class struggle”; “Conditions for the sale of the commodity ‘labour-power’”; “The production of absolute and relative surplus-value”; “How ‘normal’ conditions for the consumption of the commodity ‘labour-power’ are determined by the worker’s struggle against the capitalist”; and “The strike struggle, trade unions and factory legislation in the history of the struggle for shorter working hours” (Lenin, 1911).

How to study political economy?

Political economy must be based on a materialist and dialectical philosophy. “Only the materialist conception of history can bring light into this chaos and open up the possibility for a broad, coherent, and intelligent view of a specific system of social economy as the foundation of a specific system of man’s entire social life” (Lenin, 1898).

Political economy must be both theoretical and empirical. For example, in his The Development of Capitalism in Russia, Lenin first deals with “the basic theoretical propositions of abstract political economy on the subject of the home market for capitalism” which then serve “as a sort of introduction to …the factual part of” his book, and “relieve us of the need to make repeated references to theory in our further exposition” (Lenin, 1899b). One must, however, refrain from “superficial generalisations based on facts selected one-sidedly and without reference to the system of capitalism as a whole” (Lenin, 1908). In using statistical data from surveys produced by the state, one has to be mindful of the fact these surveys are inaccurate, in part because of their class biases (Lenin, 1912a).

Political economy must also produce ideas about what is to be done. Lenin’s famous dictum of “Without Revolutionary theory, there can be no Revolutionary Movement” (Lenin, 1901a) applies to theory in political economy.

Like philosophy, political economy is partisan. Class relations broadly informed his political economy. In a class society, there cannot be epistemic or political neutrality. “To expect science to be impartial in a wage-slave society is as foolishly naïve as to expect impartiality from manufacturers on the question of whether workers’ wages ought not to be increased by decreasing the profits of capital” (Lenin, 1913a). “[A]ll official and liberal science”, i.e. bourgeois professorial political economy, “defends wage-slavery, whereas Marxism has declared relentless war on that slavery.” As Lenin says in What Is To Be Done?, ideas and thinkers are either bourgeois or socialist: “There is no middle course … in a society torn by class antagonisms” (Lenin, 1901b). An idea/“ideologist” that is in between must choose sides, although petty bourgeois political economy vacillates between the two. Thus there are three kinds of political economy.

Given his class approach to political economy, which meant economic matters must be seen from the standpoint of the different classes, Lenin is unsurprisingly very critical not only of petty bourgeois, populist or Proudhonist political economy, but also of what he called “bourgeois and professorial political economy”(Lenin, 1899a), including the social democratic type. He said: “the personal qualities of present-day professors are such that we may find among them even exceptionally stupid people… But the social status of professors in bourgeois society is such that only those are allowed to hold such posts who sell science to serve the interests of capital, and agree to utter the most fatuous nonsense, the most unscrupulous drivel and twaddle against the socialists. The bourgeoisie will forgive the professors all this as long as they go on ‘abolishing’ socialism [through their lectures]” (Lenin, 1914).

Lenin’s specific substantive political economic claims were about: class relations and class differentiation, including in rural areas; forms and stages of uneven development of capitalism; obstacles to democratic politics caused by the capitalist economy; dynamics of capitalism, imperialism and war; conditions of workers and peasants, including women and children; and impoverishment and inequality. I will present some of his claims in the form of theses.

Lenin’s substantive claims in political economy

Thesis 1: A society based on commodity economy must experience class differentiation. When petty producers, including peasants, buy inputs and sell outputs, gradually most of them will lose their means of production and become propertyless or property-poor wage workers, while some of them will turn into proto-capitalists (rich peasants) or capitalists (capitalist farmers).

While both petty producers and wage workers perform labour, that does not mean they belong in the same category. “It is not labour that is a definite category of political economy, but only the social form of labour, the social organisation of labour, or, in other words, the mutual relations of people arising out of the part they play in social labour” (Lenin, 1902).

Thesis 2: Petty production is not viable. Petty bourgeois strata are constantly produced, pauperized and proletarianized. Its continued existence is at great costs to petty producers.

Petty producers cannot normally compete with large scale commercial producers. “The technical and commercial superiority of large-scale production over small-scale production not only in industry, but also in agriculture, is proved by irrefutable facts” (Lenin, 1908).

To the extent that small-scale production exists, it “maintains itself … by constant worsening of diet, by chronic starvation, by lengthening the working day, by deterioration in the quality [of its means of production, including cattle].”

Thesis 3: Capitalist development takes many forms at different points in times and in different countries.

“[I]nfinitely diverse combinations of elements of this or that type of capitalist evolution are possible” (Lenin, 1899b:33). Capitalism can develop when feudal-type property owners turn capitalists or when petty producers are differentiated into capitalists and wage workers. While capitalism requires property-less workers, it can make use of workers with small amounts of property that subsidize the value of labour power. Capitalism develops from commodity production through manufacture to machine-based large-scale production to imperialism.

Thesis 4: Capital exists in different forms such as industrial/productive, financial/usurer, mercantile, etc. They are united by the drive to invest money to make more money, as indicated by Marx’s general formula of capital.

Thesis 5: Capitalist development results in absolute and relative impoverishment, rising inequality and worsening health conditions for workers (and petty producers). Decentralisation of capital in the form of people’s savings is an illusion.

“The worker is becoming impoverished absolutely… But the relative impoverishment of the workers, i.e., the diminution of their share in the national income, is still more striking.”

Capital, which throws the whole of its crushing weight upon the ruined small producers and the proletariat, constantly threatens to force the conditions of the workers down to starvation level and condemn them to death from starvation.

On the other hand: “the wealth of the capitalists is increasing at a dizzy rate”. “Big capital, gathering around itself small sums of shareholders’ capital from all over the world, has become more powerful still. Through the joint-stock company, the millionaire now has at his disposal not only his own million, but additional capital gathered from petty proprietors” (Lenin, 1913).

Thesis 6: Capitalism subjects women and child labour to special exploitation, both in the petty production sector and large-scale industry. They suffer the consequences of competition between the petty production and capitalist sector, and from competition within the latter sector.

Thesis 7: Workers’ struggle makes a difference to their living conditions, but within narrow limits.

“Only as a result of this resistance, despite the tremendous sacrifices the workers have to make in the struggle, are they able to maintain anything like a tolerable standard of living” (ibid.). Yet, capital not only makes workers’ economic conditions difficult. It also makes their resistance difficult in the same process: “capital is becoming more and more concentrated”, and its “associations are growing”, while “the number of destitute and unemployed people is increasing, and so also is want among the proletariat”, as a result of which “it is becoming harder than ever to fight for a decent standard of living” (ibid.). Secondly, even if wages rise, wages do not rise much, “even with the most stubborn and most successful strike movement” (Lenin, 1912b).

Thesis 8: Capitalism produces new forms of uneven spatial and sectoral development in part because not all areas in a country are equally connected to the world market. Capitalism also produces urbanization and ruralization of capitalist accumulation resulting in a landscape that contains industrial towns, suburbs, rural industrial centers, etc. Uneven development causes migration across and inside countries. Migration in turn undermines social and spatial seclusion and causes intermingling of workers of different parts of the world, elevating them culturally and making them parts of one united world working class, even though the ruling class tries to divide them on the basis of nationalism, etc.

“The bourgeoisie incites the workers of one nation against those of another in the endeavour to keep them disunited” (ibid.).

Thesis 9: Capitalism has a tendency to be a global system.

Echoing the Communist Manifesto, Lenin said: “Capitalism cannot exist and develop without constantly expanding the sphere of its domination, without colonising new countries and drawing old non-capitalist countries into the whirlpool of world economy” (ibid.).

Thesis 10: Capitalism at its highest stage develops into imperialism, which necessarily promotes wars, warmongering and political reaction. There is an economic essence of imperialism, which cannot be reduced to mere government policies of annexation or militarism (Lenin, 1916a, b).

Thesis 11: Capitalism was progressive relative to pre-capitalist society in that it created conditions for socialist society, but it has now turned into a reactionary social form, at least since the early part of the 20th century. It turned reactionary because it feared “the growth and increasing strength of the proletariat” (Lenin, 1913c). So, it “comes out in support of everything backward, moribund and medieval”, it joins “with all obsolete and obsolescent forces in an attempt to preserve tottering wage-slavery”, and it “is prepared to go to any length of savagery, brutality and crime in order to uphold dying capitalist slavery” (ibid.).

Thesis 12: Lenin’s political economy produces ideas about what is to be done: it points to the significant reforms under capitalism that workers must fight for and to the transitional measures that a proletarian party must take following the overthrow of capitalism (for example, a new economic policy where the state may have to temporarily allow a degree of capitalist development under strict supervision), as part of a more or less uninterrupted struggle to establish communism. Lenin rejected the idea that successful socialist construction could happen in a single country, although revolutionary measures could be undertaken in a single country.

A comradely critique of Lenin

There are several problems with Lenin’s political economy.

Lenin rightly thinks crises are “not a thing of the past” and that prosperity is followed by a crisis. Also that while “the forms, the sequence, the picture of particular crises change”, crises remain “an inevitable component of the capitalist system”. But his crisis theory is inadequate. His is often an overproduction or even under-consumptionist theory: “Industry could produce hundreds of thousands of motor vehicles but the poverty of the masses hampers development and brings about crashes after a few years of ‘brilliant’ growth” (Lenin, 1913). He abstracts from Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall as a result of the organic composition rising faster than the rate of exploitation.

Lenin also says little about how capitalism at the national scale is itself a barrier to the development of productive forces. There is little recognition of ecological problems or of the role of the state in economic management of capitalism (except in terms of his comments on regressive taxes). In spite of these problems, Lenin’s contributions to political economy are priceless.

Raju J Das is Professor at the Faculty of Environmental and Urban Research, York University. https://rajudas.info.yorku.ca

References

Lenin, V. 1898. Book Review: A. Bogdanov. A Short Course of Economic Science. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1898/feb/bogdanov.htm

Lenin, V. 1899a. Review of Hobson's Imperialism. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1899/apr/hobson.htm

Lenin, V. 1899b. Development of capitalism in Russia. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/cw/pdf/lenin-cw-vol-03.pdf

Lenin, V. 1901a. What Is to Be Done? https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/witbd/i.htm

Lenin, V. 1901b. What Is to Be Done? II. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/witbd/ii.htm

Lenin, V. 1902. The Union of the Russian Social-Democrats Abroad. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1902/nov/01.htm

Lenin, V 1908. Marxism and revisionism. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1908/apr/03.htm

Lenin, V. 1911. Plan for a Lecture in a Course on “Fundamentals of Political Economy” https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1911/jan/27.htm

Lenin, V. 1912a. Workers’ Earnings and Capitalist Profits in Russia. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1912/aug/08b.htm

Lenin, V. 1912b. Impoverishment in Capitalist Society https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1912/nov/30.htm

Lenin, V. 1913a. The Three Sources and Three Component Parts of Marxism https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1913/mar/x01.htm

Lenin, V. 1913b. The Growth of Capitalist Wealth. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1913/jun/09b.htm

Lenin, V. 1913c. Backward Europe and Advanced Asia. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1913/may/18.htm

Lenin, V. 1913d. A “Fashionable” Branch of Industry https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1913/jul/21.htm

Lenin, V. 1914. A Liberal Professor on Equality https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1914/mar/11.htm

Lenin, V. 1916a. Karl Marx. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1916/carimarx/3.htm.

Lenin, V. 1916b. Imperialism: the highest stage of capitalism https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1916/imp-hsc/

- 1

This is a version of my text for the plenary on ‘100 years after, Lenin’s contribution in political economy’ at the World Association of Political Economy conference held in Athens, Greece on August 2-4, 2024. This text has been extracted from a much longer paper.