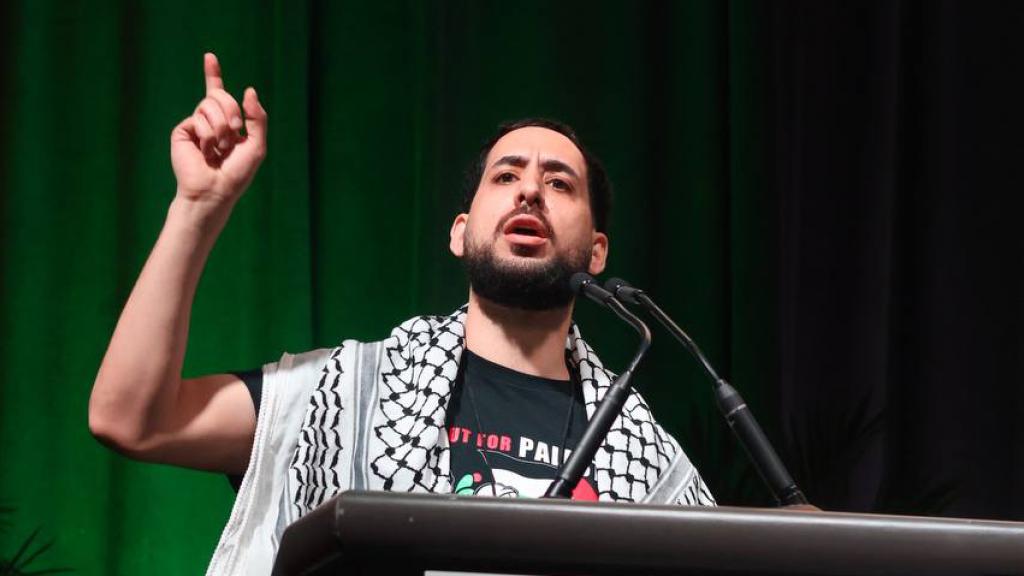

Mohammed Nabulsi (Palestinian Youth Movement): The strategy of the movement for Palestine in the belly of the beast

First published at Peoples Dispatch.

The Palestinian Youth Movement is a national formation. We exist across multiple locales, across three countries, and so we’re one of the few organizations in the movement that is coordinated across different cities. We’re deriving lessons and gaining experience from different conditions, synthesizing them, and trying to apply a strategy nationally.

That’s not something that typically happens, because it’s very difficult to coordinate across so many different contexts and conditions. From the West Coast to the East Coast to the South, the Midwest, the conditions are so different depending on the state government, depending on the local communities, and things of that nature.

We’ve grown so much as a movement. We’ve achieved so much and it’s taken decades and decades of work. The Oslo Accords that occurred in the early 1990s, that effectively dissolved Palestinian national institutions outside of Palestine. It was extremely devastating for the movement for Palestinian liberation and the diaspora, because the national institutions that gathered, organized, politicized, gave voice to our communities, over time disappeared.

And what happened was the solidarity movement emerged as the primary and sole vehicle for political organizing in this country. In a way, it saved the movement because it continued the struggle despite the change and the transformation in the conditions in Palestine.

Whereas before, prior to the Oslo Accords, there was way more centralization, especially through the major vehicles for Palestinian work in this country. Institutions like the General Union of Palestinian Students (GUPS), which today solely exists on San Francisco State University’s campus, contrasted with the eighties, where there were thousands upon thousands of Palestinian students who were among the rank of the GUPS movement, which was obviously still tied to the PLO at the time.

So this lack of centralization prevents us as a movement from being able to centralize a strategy in a way that allows the tactics to have the most effectiveness, but that’s a feature of organic organizing. Sometimes you don’t have centralization, sometimes you don’t have consolidation, but nevertheless it makes it to where we have to study our circumstances and the tactics and strategies that have been employed over the last eight months, in hindsight, as opposed to setting a strategy, seeing what happens and then revisiting after time.

The number one goal that we’ve had up until now over the last eight months is to secure a ceasefire. I don’t need to say this, but I’m going to say this, a cease fire is the floor of our demands. Nevertheless, when you have a moment where the people of Gaza, the people of Palestine, are being genocided, and the number one ask has to be to stop that genocide.

You have to calibrate your tactics and your strategies in light of that goal. We have a goal around lifting the siege. We have a goal around ending the occupation, around freeing our political prisoners, around so much more than just ending this genocide. But right now, we have to assess the strategic logic of the tactics employed through the vantage point of: what have we been able to do in order to bring us to an end to a genocide?

Mass mobilization is the primary tactic. It’s pouring people, thousands and millions, into the streets. What that does is it signals our political strength. It lets everyone around us, and the powers that be understand that we have the masses underneath the politics of the Palestine movement.

These mass mobilizations have happened in consistent and sustained ways, and they have happened towards specific targets. There’s a lot that can be said about the significance and importance of mass mobilizations for the long term health and growth of the movement, of bringing people into movement, of agitating, of educating, of all of the work that you all are doing on a day in and day out basis.

Then we have all of the different things related to mass mobilizations, but not necessarily requiring them. Street shutdowns through unsanctioned marches, bridge and train shutdowns, airport caravans and shutdowns, encampments, building takeovers, targeting of weapons manufacturers, shutting down events, bird dogging, all of the things that we’ve seen throughout these last eight months.

We’ve also seen the efforts to advance ceasefire resolutions and ceasefire statements through city councils, and popular institutions like unions, and sector-based organizations, mainstream media, different industries, etc. We’ve also seen this through the uncommitted vote movement that took place over the last few months during the primaries, that was able to do the same thing that the mass mobilizations did in terms of signaling our numbers, showing the power that we have.

Understanding there is no centralization, despite the fact that a lot of our opponents and those in Congress have this amazing imagination where they think that there’s this sole central body somewhere else coordinating us all, whether it’s George Soros, or the Communist Party of China, or whoever.

But I believe that the strategy, though it hasn’t been articulated, or even cohered in this way, was to wage a battle on every front, agitating and implicating the broader institutional life within the West.

Beyond waging a struggle and generating pressure on every front, the question we’re asking ourselves is: What is the fundamental strategic logic governing these different tactics? And which decision makers are we trying to force into taking different decisions? Who are we trying to push, and to what end? Who are our targets? These questions are really important for us to have clarity on. We can get lost in the conversation about which tactics to use, which forces us to lose sight of, well, why are we using this tactic, who is it impacting, and what are we trying to get them to do?

We need to be clear. The chief target has been the Biden administration. Ultimately, the Biden administration, and to an extent the Democratic Party, is the primary vessel that controls the policies and the decisions that actually impact our people in Gaza. While we can have a long term vision around different issues—including divestment, even though I believe divestment is also a part of the front that allows us to create more pressure towards the Biden administration—the short term, most immediate goal is to get the Biden administration and the Democratic Party, to end its trajectory in support of this genocide.

We don’t do this because we have faith in them. We don’t do this because we believe that there’s some way we can alter their conscience, make them more moral actors, appeal to their moral sensibilities. That’s not why. We do this because ultimately they control the levers of power. We need those levers to be lifted off our people in Gaza.

How do these tactics tie to targeting the Biden administration and the Democratic Party? I believe our fundamental role is to generate political and social crisis within the American ruling class.

What does it mean to generate crisis for the ruling class of this country? It means to make this the continued prosecution of this war politically, socially and economically untenable. It means to create further divisions, ruptures, conflicts, and problems for and amongst the Western ruling class, the Biden administration, the Democratic Party and the base of the Democratic Party.

In my opinion, this is the main constellation of actors, organizations, and forces that we have actually targeted. I believe that most, if not all of the tactics utilized can be understood through this framework, as creating and generating crisis.

[Regarding generating crisis for the ruling class], there’s disrupting the war machine, which we all believe needs to happen. But sporadic disruption of the war machine, including shutting down a weapons manufacturer, is not going to effectively disrupt the war machine, even though it’s something we should do, and continue to do. But we must understand its limits, not in terms of it as a tactic, as every tactic is limited, but understand the tactic as implemented by the movement that currently exists. That’s how it must be calibrated.

The second is making it economically untenable. The economic costs for Western and Israeli companies, with BDS as the vehicle, even that is a much more long term project than the immediate goals of generating social and political crisis for the Democratic Party.

I’ll turn to lessons that I think we should take away in light of these considerations. Whenever we make this assessment, we have to assess: what is our movement currently like? What currently exists? I mean it in a literal sense: what organizations, what infrastructure, and I mean media, finances, etc. We have to think about it in terms of our actual coordination, our ability to work together. It might appear that we’re so coordinated as a movement, and there are certainly coalitions and coordination happening, there’s no doubt, but not at a level that one can say is consolidated enough to be the implementation of a strategy from a centralized body onto the ground. That’s not how it works. So we have to think about what the movement looks like, what are the tactics at our disposal and what are our targets.

Our capacity to generate the crisis that we have generated up until this point, and we have done this, it must be said—There’s a bit of a, I want to call it nihilism, because I believe it’s nihilism. This idea that everything we’ve done has been for naught. That we haven’t achieved anything, that the war is raging on. There’s a mistake in the logic of this type of thought process. It overemphasizes and overstates our subjectivity, meaning our individual thoughts about the role we’re playing, as opposed to looking at how we can materially contribute as a front in a war.

We are one front. We are not the sole front. We are not the front. This genocide will come to an end, in part, because of all of the work that we’ve done. But that’s the key word here: in part. Not because of us.

There’s other actors involved. Chief among them are the people in Gaza. The actors in the regions, the state actors, like South Africa and the ICJ and the ICC. We don’t put our faith in these institutions or in these strategies necessarily on their own, but understanding them as a part of a broader struggle, that needs every front mobilized in this moment to bring this genocide to an end.

The idea of diversity of tactics is really important. This is a phrase that gets thrown around a lot, but I want to concretize it. A lot of bodies, movements, and institutions follow different strategies and build towards those strategies at the same time. Sometimes those strategies are competing, sometimes they’re in conflict, sometimes they overlap, sometimes they’re complimentary. What we’ve seen these last eight months is that all of the strategies pursued have benefited us.

I’m a grassroots organizer at heart. I’m not big on electoralism. I’m not big on a lot of the stuff that takes place, especially in relation to the Democratic Party. I’m sure a lot of you will relate on this question. But I’ve also now understood that the role of the uncommitted votes movement in helping to bring this genocide to an end. We needed something like that.

We have to figure out at some point how we’re going to navigate the contradictions that emerge as a result of the pursuit of different strategies, between us as organizers. That’s an internal conversation, in my opinion, to be had. Who are our core constituencies? Which bases of support that were mobilized in the eight months really proved fruitful?

I want to say something that I think is often neglected by the Palestine movement, but the Islamic institutions in the Muslim community, that’s been our primary base, in my opinion. The Masjids, the Muslim American Society (MAS), the Islamic Circle of North America (ICNA), the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), all of these different vehicles. They’ve been critical. They’ve been very important for us in our ability to register that we have power in this country. We need to cultivate stronger relationships with these different core constituencies.

Mohammed Nabulsi is a longtime organizer in the Palestinian struggle, including within the student movement as student at the University of Texas at Austin. He is now a leading organizer in the Palestinian Youth Movement, a major political formation within the movement for Palestine in the diaspora.

Nabulsi spoke at the People’s Conference for Palestine, held from May 24 to 26 in Detroit, Michigan, at a plenary session entitled “The Movement for Palestine in North America,” in which he addressed the most relevant debates within the movement such as the necessity of mass mobilization, the diversity of tactics, chief targets of the movement, and overall strategy. This transcript of his speech has been lightly edited for clarity.