Surplus profits, capital exports and imperialism: An interrogation of commonly held beliefs and assumptions

The following contribution aims to interrogate commonly held beliefs and assumptions concerning monopoly capital, surplus profits, surplus capital and the export of capital. It will explain that such beliefs are not coherent. The arguments that follow are not empirical, though actual data from France in 2018 shall illustrate their logic and provide source references.

A short summary of the commonly held beliefs with which I am concerned goes something like this: there exist countries in which the dominance of monopoly capital generates aggregate surplus profits but concomitantly limits domestic opportunities for their continued profitable investment. Surplus profits are synonymous with super profits. They accumulate as surplus capital. Pent up surplus capital in these countries thereby tends to generate enormous pressure that finds release in the form of capital exports: that is, investment in the rest of the world, especially in developing countries.

Can these beliefs withstand scrutiny? Note that the issue is not whether multinational corporations take advantage of higher offshore returns, potentially greater risk notwithstanding. They do. Nor is it about strategic offshore investments for product market access or to secure supplies of raw materials. Nor does it concern “offshoring” of production. These are part of the quotidian work of profit-seeking enterprises. Rather, the concern of the present contribution is how such everyday occurrences aggregate across economies and, potentially at least, shape global economic and political arrangements. Specifically, is it possible that surplus profits/capital and capital exports might be at the heart of enduring, global economic relationships that define what we have come to call “imperialism”?

Standard arguments

To elaborate on the brief summary above, it is tempting to start with Vladimir I Lenin’s Imperialism (1916). There is, however, an earlier exposition that presents the argument clearly and is notable for shaping Lenin’s thinking. The Fabian socialist John A Hobson’s Imperialism: A Study (1902) is seminal. For Hobson, a “new imperialism” had emerged in the last quarter of the nineteenth century as a national policy with a distinctively “economic taproot” (1902, p. 89). He sketched the outlines of the new imperialism in an imagined justification espoused by the “Imperialists” (1902, pp. 81-3):

We must have markets for our growing manufactures, we must have new outlets for the investment of our surplus capital … a necessity of life to a nation with our great and growing powers of production. An ever larger share of our population is devoted to the manufactures and commerce of towns, and is thus dependent for life and work upon food and raw materials from foreign lands. In order to buy and pay for these things we must sell our goods abroad … Far larger and more important is the pressure of capital for external fields of investment … Of the fact of this pressure of capital there can be no question. Large savings are made which cannot find any profitable investment in this country; they must find employment elsewhere … [I]f we abandoned [the policy of imperial expansion] we must be content to leave the development of the world to other nations, who will everywhere cut into our trade, and even impair our means of securing the food and raw materials we require to support our population. Imperialism is thus seen to be, not a choice, but a necessity.

Hobson aimed to add economic sophistication to his criticism of the Imperialists. On the one hand, he both emphasised and linked the roles of effective demand and the unequal distribution of wealth and income in creating chronic overproduction due to underconsumption. On the other hand, he highlighted the concentration of capital into trusts and combines and linked this with the tendency to limit domestic investment and accentuate overproduction. Already, under a more competitive capitalism, productive capacity had exceeded consumption demand, but concentration introduced a new dynamic (1902, pp. 85-8). It is hard to think of anything in the twentieth century literature on monopoly and imperialism that had not already been foreshadowed by Hobson. Too often treated, in Marxist circles at least, as a mere footnote to Lenin, Hobson’s Imperialism deserves to be treated, as Lenin noted in the first paragraph of the 1917 Preface to his own Imperialism (1916, p. 634), “with all the care that, in my opinion, that work deserves.”

We should note that both Hobson and Lenin were writing on the subject well before the development of modern national income accounting methods and data. Nevertheless, Lenin’s “pamphlet, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, written in 1916 in response to the outbreak of war” has had a “towering influence” (Amsden 1987, pp. 207-8) on Marxist theorists of imperialism to this day. Alice Amsden hones in on Lenin’s definition of imperialism, which follows Hobson in seeking the “economic taproot”: “Whereas in common usage imperialism means forced economic gain on a global scale, to Lenin it means much more. The most concise definition he gives is ‘imperialism is the monopoly stage of capitalism’, uniquely characterized, it should be added, by capital export.” Here is a sample from Imperialism (Lenin 1916, pp. 678-9; emphasis added):

Typical of the old capitalism, when free competition held undivided sway, was the export of goods. Typical of the latest stage of capitalism, when monopolies rule, is the export of capital … On the threshold of the twentieth century we see the formation of a new type of monopoly [and] … in which the accumulation of capital has reached gigantic proportions. An enormous “surplus of capital” has arisen in the advanced countries … As long as capitalism remains what it is, surplus capital will be utilised not for the purpose of raising the standard of living of the masses in a given country, for this would mean a decline in profits for the capitalists, but for the purpose of increasing profits by exporting capital abroad to the backward countries. In these backward countries profits are usually high, for capital is scarce, the price of land is relatively low, wages are low, raw materials are cheap … The need to export capital arises from the fact that in a few countries capitalism has become “overripe” and (owing to the backward state of agriculture and the poverty of the masses) capital cannot find a field for ‘profitable’ investment.

Another example of this classical argument comes from Ernest Mandel’s definition of “Monopoly capitalism (Imperialism)” in his major work Late Capitalism1 (1975, pp. 594-5):

… a qualitative increase in the concentration and centralization of capital leads to the elimination of price competition from a series of key branches of industry … A trend to regulate (i.e., limit) investment and production in monopolized sectors henceforth prevails, in spite of the existence of monopolistic surplus-profits [“specific forms of surplus-profit originating from obstacles to entry into special branches of production”, the general forms of which are “profits over and above the socially average rate of profit”, pp. 595, 597], so that over-accumulation [“a state in which there is a significant mass of excess capital in the economy, which cannot be invested at the average rate of profit normally expected by owners of capital”, p. 595] leads to a frantic search for new fields of capital investment and hence to a growth of capital exports.

Here is a more recent example from David Harvey (2021, pp. 92-3):

When the rising mass of capital can no longer be absorbed within its home territory, investors develop strategies to export the surplus mass through spatial fixes, to absorb over-accumulated capital. In the US, a great deal of surplus capital was absorbed internally through the development of the “sunbelt” South and West … By the 1970s, however, the question of surplus absorption became pressing, if not paramount. Internal saturation also led Japan to look outwards, followed by South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore. After 1978, Beijing broke the Cold War embargo and began to absorb vast amounts of capital, much of it from the other East Asian countries. By 2000, though, the internal market in China was approaching saturation … the PRC also turned outwards … While some of this is driven by geopolitical jockeying for power and position, one can plainly identify the politics that attaches to falling rates [of profit] and rising masses of capital.

Almost every piece of the Marxian economics jigsaw — from theories of monopoly and underconsumption to those of the declining rate of profit and overproduction — competes for a place that fits in explaining the export of capital. They each culminate in forming an image of masses of surplus capital that roam the globe in search of super-profits, in much the way that William B Yeats’s rough beast slouched its way towards Bethlehem.2 As the task here has a narrower scope, I must set aside some pieces of the jigsaw and refer readers elsewhere. For example, Marx’s theory of the declining rate of profit was the subject of an earlier work3, and there are separate contributions to the discussion of imperialism.4

Identities, causality and definitions

To set the framework for the following discussion, we must take as read basic national-accounting principles and definitions, namely that:

- households’ total spending C+ — principally consumption, but including the purchase of new dwellings and capital spending by the self-employed — plus

- corporate investment spending I plus

- total general government consumption and investment spending G plus

- net exports, or exports less imports NX, will both be equal to and cause the volume of

- gross domestic product (GDP) Y.

Moreover, the disposable incomes5 derived from aggregate spending Y result, in turn, from the various distributional mechanisms in play (industrial conflict over productivity, wages and profits, taxation policy, government and corporate income transfers, and so on). The disposable income categories correspond, in their turn, to the institutional units or sectors responsible for the specific kinds of spending above. Thus:

- aggregate spending Y (or GDP or national income) causes and is equal to, via mechanisms of distribution, the sum of

- household disposable income H plus

- corporate disposable income, or gross profits6 after tax, interest, dividends and rent P plus

- general government disposable income T plus

- all forms of income attributable to, less those earned from, the rest of the world NO.7

Hence, the following identities hold, with aggregate causality accounted for by the spending (demand) variables (those on the left-hand side of [1]):

C+ + I + G + NX = Y = H + P + T + NO [1]

P = I + (G - T) + (C+ - H) + (NX - NO) [2]

(P – I) = (G – T) + (C+ – H) + (NX – NO) [3]

(NX – NO) = (P – I) + (T – G) + (H – C+) [4]

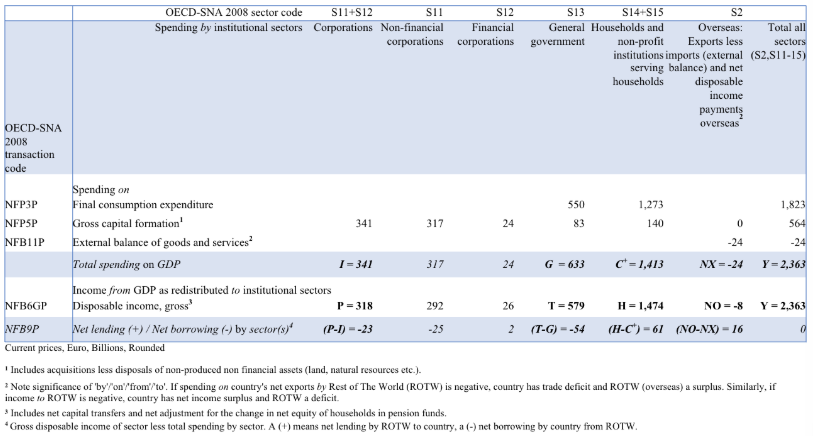

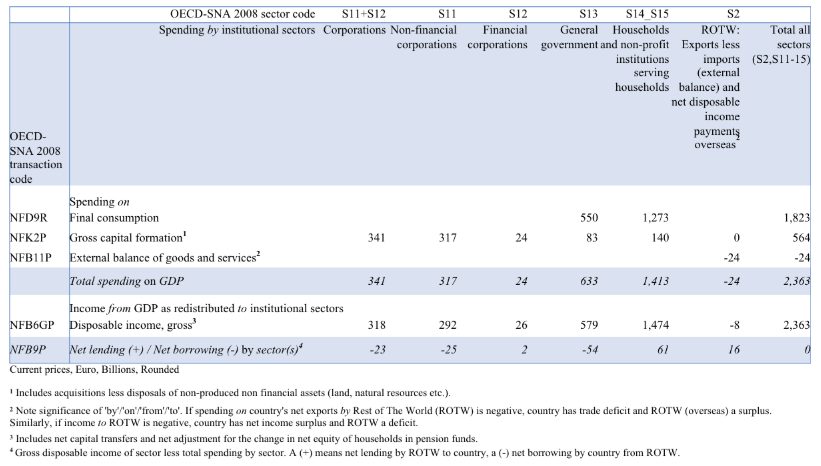

Figure 1 sets out the variables and relationships contained in [1]-[4]. It uses actual data for France 2018 derived by the author from the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development national accounts statistics database (OECD 2023, Table 14A). The categories follow the System of National Accounts, 2008 (SNA 2008).8 The subsequent illustrations shown in Appendix 1 follow from Figure 1 and derive coherently from it. The illustrations include OECD SNA 2008 reference codes. Readers can check for themselves whether the logic and illustrations below are sound or not.

What then are corporate surplus profits? Consistent with arguments such as those quoted in the preceding sections, we should define aggregate surplus profits coextensively with surplus capital. The one creates the other. Now, the only way that some proportion of aggregate corporate profits can be “surplus” is that, in any given year, they are greater than aggregate domestic corporate capital investment. This is the only logical sense in which they can be excess (surplus) to profitable domestic investment and available for export. This is also the only logical sense in which such surplus profits can accrue over time in the national balance sheet as financial assets rather than being part of the capital stock of buildings, plant and equipment, etc acquired by investment spending. That is, such financial assets are surplus capital by definition.

In [3] and Figure 1, surplus profits are P – I. In the illustrative data they are negative (-€23b). In other words, corporate gross capital investment in France in 2018 (€341b) exceeded corporate disposable income or profits (€318b). This is the same as saying, in the words of the SNA 2008, that France’s corporate sector was a net borrower in 2018. In 2018, it neither made surplus profits nor accumulated them as surplus capital/financial assets.

Note also that our primary interest is in net not gross financial assets. Most increases in gross financial assets simply correspond with increases in gross liabilities. A simple example is when an entity belonging to one or other institutional sector borrows funds to purchase shares. Here one financial form, share-holdings (asset), matches another, increased debt (liability). Net financial assets can only change in any year to the extent of a sector’s net lending or borrowing. This is equivalent to the extent to which its disposable earnings exceed its spending. For corporations, therefore, net financial assets rise or fall only to the extent of the gap between gross disposable profits and investment spending. Having set out this framework of relationships — that is, of identities, definitions and causalities — we can now turn to the arguments.

Necessary conditions

The approach here involves establishing the conditions necessary for surplus profits/capital and capital exports to be possible.9 The five cases below call upon what is often called Kalecki’s (or the Kaleckian) profit equation, which is a class analogue of the national-accounting form [2] above.10 In addition to satisfying Kalecki’s causal logic and national-accounting requirements, the necessary conditions we require must account coherently for a country’s international financial flows. The SNA 2008 and the IMF Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual, Sixth Edition (BPM6 2009)11 now refer to their balances as a country’s net lending to, or borrowing from, the rest of the world. The most relevant identity above is [4]. As does Figure 1, [4] shows the equivalence between a country’s domestic sectors’ total income less spending and its net transactions with the rest of the world. These, in turn, are equivalent to its net capital exports or imports. Because international economic accounting can be unfamiliar territory, Appendix 2 supplements Appendix 1 with an additional tabular summary extracted from BPM6 (2009), together with a brief descriptive explanation and source references.

(i) Base case

To begin, we focus solely on corporations by considering the case in which households do not save, governments have neither deficits nor surpluses, and the country is in balance with the rest of the world. The first conclusions in this base case are that aggregate corporate profits P are both caused by and equal to corporate domestic capital investment I. This constitutes Kalecki’s basic profit equation. Inserting zero values for households, government and the rest of the world into [2] and [3] above gives:

P = I + (0) + (0) + (0) [2.1]

(P – I) = (0) + (0) + (0) = 0 [3.1]

In these conditions, there can be no such thing as aggregate surplus profits or aggregate surplus capital. To suggest otherwise, perhaps by assuming that businesses collectively might invest less than the profits they earn, combines two antediluvian12 fallacies: 1) causality runs from aggregate profits to aggregate capital-spending, and 2) what might hold for individual firms can hold in the aggregate. It is essential to grasp the causal role of capital investment spending. It is imperious.13 If firms collectively were to taper their level of capital investment spending to try to accumulate reserves of retained surplus profits to fund future capital investments, they should neither earn those surplus profits nor accumulate the desired reserves of surplus capital. An individual firm might succeed in accumulating retained profits in this way14 but, in base-case conditions, it is impossible for firms to do so in aggregate.

It is also essential to grasp the simple fact that capital investment spending is not constrained causally by profits. Another way of saying this is that profits are not causally prior to capital investment spending. Investment, so to speak, does not come “out of already earned profits”. The “comes out of profits” way of thinking creates an intellectual straitjacket. The opposite is true. Capital investment can be externally credit-financed, in whole or in part. Moreover, credit-financing is causally independent of saving by other institutional sectors. Households, for instance, do not have to save in order that corporations can invest. Access to credit means that investment spending will include, but not be bound by, corporations’ internal-financing, the application to investment of firms’ internal financial assets. In particular, investment is not necessarily bound by the quantity of those financial assets that correspond to accumulated depreciation provisions.15 It is not that individual firms do not apply accumulated depreciation to new or capacity-replacing investment. They do. It is that they do not necessarily have to.

A telling criticism of Mandel (1975) by Bob Rowthorn (1976, p. 64, emphasis added) makes just this point. The quotation is long but worthwhile:

During an expansionary phase, there is a very high level of investment which, Mandel [1975] says, is financed out of reserve funds already in existence when expansion begins; these funds, he argues, were built up in the course of several industrial cycles, during the preceding non-expansionary phase of the long wave. In the non-expansionary phase, capitalists have an excess of capital which they place in reserve funds; later, when expansion begins, they use these funds to finance a large-scale investment programme. This argument is mistaken. Once expansion gets under way, it is self-supporting; profits are high and provide a sufficient flow of money to finance investment on the required scale; capitalists then have no need for the “historical reserve fund of capital” on which Mandel lays so much stress. The only time when such a reserve might be necessary is in the initial stages of expansion, before profits have started to flow on a large enough scale to finance investment. But, even then, there is an alternative source of finance, namely bank credit. When expansion begins economic prospects are good, anticipated profits are high and banks are prepared to lend, confident their loans are secure. Thus, firms can finance their initial investment by borrowing from the banks. Later, as profits start to flow, they can use their own internally generated funds. Now the key point about bank credit is that it can increase total purchasing power in the economy. Banks are not merely a funnel through which other people’s savings are channelled. They can actually create new purchasing power … [and] can provide investment finance in excess of what has already been saved by capitalists or anyone else. When they do this, banks are not lending reserve funds built up in the previous non-expansionary phase of the long wave. They are creating genuinely new purchasing power! Mandel has fallen victim to a well-known fallacy, that no one can lend what they, or someone else, has not already saved. The peculiar characteristic of banks is that they can do just this.

To return to the point, if household and government budgets balance, and the same situation prevails with the rest of the world, then business investment causes and equals business income such that aggregate surplus profits so defined equal zero. In the base case, then, we have answered one transcendental question: it is not possible to make aggregate surplus profits or to accrue surplus capital at all. The conditions for the possibility of surplus capital are absent.

(ii) Base case with monopoly surplus profits

However, such conclusions do not preclude the possibility that a focus on aggregates might conceal the specific role of monopoly surplus profits. After all, the ability of monopoly capital to garner surplus profits is at the crux of the arguments that we are exploring.16 Starting with [2.1] above, we can separate monopoly profits Pm and investment Im from non-monopoly profits Pn and investment In. With households, general government and the rest of the world still in balance, it is an easy matter to arrive at [3.2]:

P = I + (0) + (0) + (0) [2.1]

Pm + Pn = Im + In [2.1.2]

(Pm – Im) = (In – Pn) [3.2]

This tells us that, for monopoly surplus profits to exist, which is to say that the term Pm – Im is positive, it must be the case that non-monopoly investment In exceeds non-monopoly profits Pn. This is to say that non-monopoly investment spending is causally responsible for picking up the slack that generates monopoly super profits. This must be so because monopoly capital investment falls short of, which is to say does not generate, that slack — the gap between Pm and Im. While this conforms superficially to the claim of slackening monopoly investment, the argument is unconvincing. That capital’s economic powerhouses should depend on their poorer brethren seems to be a piece of the jigsaw that just does not fit.

Note, too, that none of this speaks to the levels of investment and, therefore, of profits. As some tinkering with the possibilities inherent in [2.2] shows, monopoly capital might make surplus but not super profits, surplus and super profits or, if the signs of [3.2] were to reverse, super but not surplus profits and neither super nor surplus profits. Note also that the base case with monopoly continues to preclude net capital exports.

(iii) Classical case

The premises of the base-case conclusion that there can be no such thing as aggregate surplus profits are not far-fetched, but they are limiting. What, then, if we were to maintain households and general governments in balance but allow that net exports NX (exports less imports) less net domestically earned income flowing to non-residents NO (non-residents’ in-country income, including profits, less residents’ income, including profits, earned abroad) should be positive? This, perhaps, represents the classical case, because it is necessary that corporate profits should exceed corporate investment. That is, from [3] above, we have:

(P – I) = (0) + (0) + (NX – NO) [3.3]

Hence, from [3.3], we can determine both that it is possible to generate surplus profits and that the necessary condition for such a possibility is that NX – NO is positive. This, in turn, just means that the spending side of this relationship NX is greater than is the income side NO. This corresponds, as Appendices 1 and 2 explain, with net lending (+) to the rest of the world. In this specific instance, since both the household and general government sectors are in balance, the corporate sector solely accomplishes a country’s net “lending” — exporting capital — to the rest of the world. So, the classical case — surplus profits conjoined with capital exports — holds. The condition for its possibility is that the rest of the world’s surplus or excess spending, if we may so call it17, supplements aggregate domestic spending via net exports.18

Now, one possible consequence of the italicised conclusion is to invalidate Lenin’s (1916, p. 678) argument that “Typical of the old capitalism, when free competition held undivided sway, was the export of goods. Typical of the latest stage of capitalism, when monopolies rule, is the export of capital.” We have just seen that, other things being equal, capital exports and the export of goods (and services) are coextensive. If Lenin did mean to counter pose them, he was wrong. The export of capital is the export of goods (and services) viewed from another perspective. It is quite possible, of course, that Lenin was trying to make a different point, for example that the dynamic emphasis had shifted between these two sides of the same coin such that the export of capital per se — the purchase of foreign assets or loans to non-resident entities on their own account, independently of trade in goods and services or flows of income — should be the active factor shaping economic relationships between countries. Whatever the case, we should be clear about what this might mean. Let us explore the export of capital per se, abstracting it for sake of argument from components of the terms NX and NO.

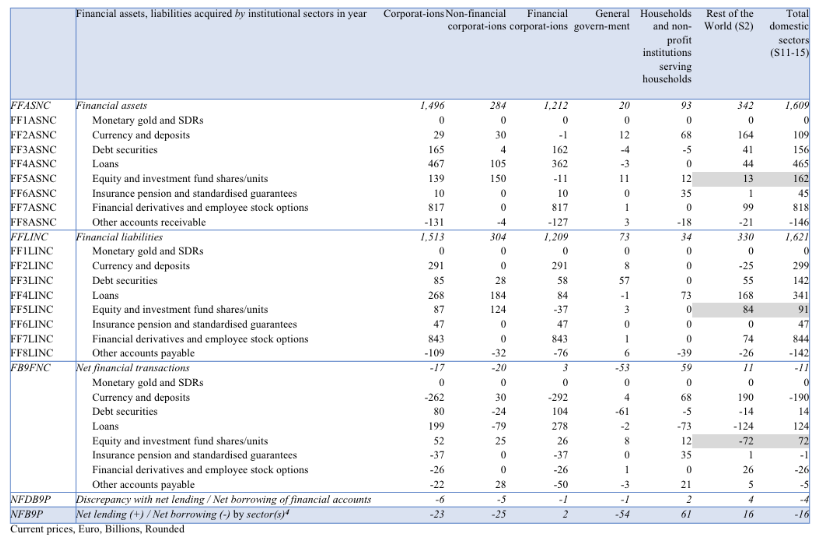

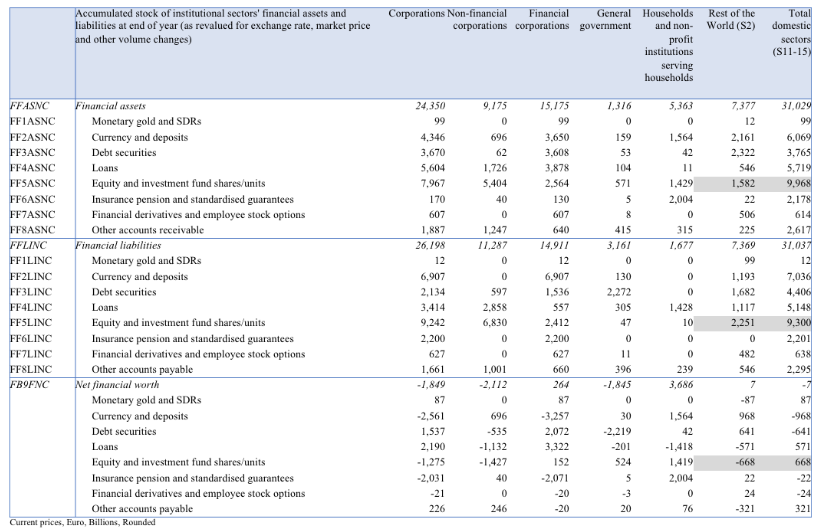

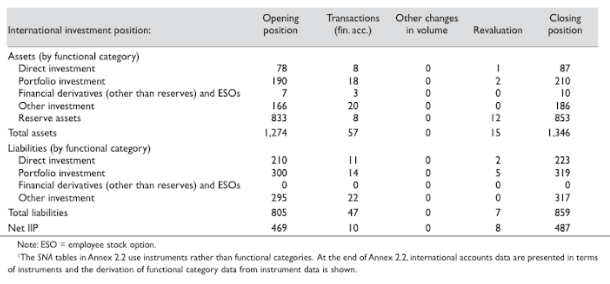

What the export of capital means is the acquisition of net overseas assets of one kind or another. Capital import is the obverse: acquisition of net liabilities to the rest of the world. The second panel of Appendix 1 illustrates the annual acquisition of such assets/liabilities by kind of financial instrument, while the third panel gives the accumulated end-of-year stocks of such assets/liabilities after revaluation. Alternatively, we may summarise these assets and corresponding liabilities by functional kind, namely:

- foreign direct investment — transactions involving ownership or control of enterprises

- portfolio investment — transactions involving debt, bonds, shares, etc

- derivatives and employee share options — financial assets the value of which derives from tradable commodities or other financial assets

- reserve assets — foreign currency holdings of central banks

- other, which comprises a grab-bag from bank deposits, cash holdings and accounts receivable/payable, to some loans, trade credits and insurances, etc, with

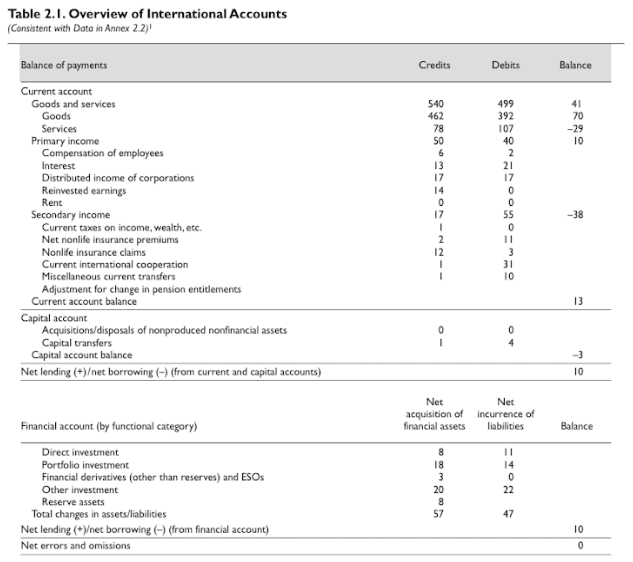

- the net balance of these items being a country’s net international investment position (NIIP), as shown in the figure from BMP6 (2009, p. 14, Overview of International Accounts) reproduced in Appendix 2.

Note that the international investment position (IIP) accounts measure stock items — assets and liabilities measured at points in time such as at year’s end. Transactions in such “capital” items by residents and non-residents occur continuously in various markets, back and forth around the clock. Consider, for example, foreign exchange market transactions, a considerable proportion of which are speculative. In April 2022, total annual foreign exchange turnover in Australia was about AUD$11.2 trillion, compared with the country’s GDP in the year to June 2022 of about AUD$2.3 trillion — a factor of almost five. The point is that such transactions in “capital” across borders are greater in magnitude than are both stocks of foreign exchange and the quantities of foreign exchange needed for balance of payments transactions, that is those resulting in the quantities described by NX – NO.

The critical point to note is this: regardless of their magnitude, “capital” transactions on their own account cannot involve the production of surplus profits or surplus capital. The reason is straightforward. “Capital” transactions involve changes in stock or balance-sheet items. Any purchase or sale of an asset must be offset by a decrease or increase in another asset (for example, bank balance) or an increase or decrease in a liability (for example, loan). The net effect of such changes is zero. This also applies across borders.

Imagine the simple case of a Swiss corporation buying a British government bond in order to increase the return on money holdings that otherwise it should have held in a Swiss bank account. Its first move involves drawing down its home bank balance in order to buy pounds at the going exchange rate to create a deposit in a British bank. It then buys the bond using pounds, drawing down its British bank balance. Setting aside exchange-rate revaluations, the corporation’s net-asset position has not changed. It now has an offshore portfolio investment rather than money at its domestic bank. Switzerland’s net position has not changed, either. It now has an increased level of portfolio investment in Britain but, because Britain now has the Swiss francs that the corporation used to buy pounds, Switzerland has an increased liability, namely an obligation it must honour should Britain cash in its holdings of francs for pounds, some other currency or gold.19

The final IIP section of the table in Appendix 2 illustrates this in principle, while also including changes in the current and capital accounts of the balance of payments. The country’s gross international assets increase by 72, while its gross liabilities increase by 54. These figures include net revaluations of 8. As can be seen, most of the movement in assets and liabilities is independent of the current and capital accounts. However, the change in the net asset position (72 – 8 – 54 = 10) occurs solely because of changes in the current and capital accounts, the financing of which the financial account records. This sits directly above the IIP section of the table and, though recorded from a functional perspective, is numerically equal to the item NX – NO recorded in Figure 1 above. The financial account thus records the foreign exchange transactions (acquisitions of net assets and liabilities) required to finance NX – NO, that is net lending (+) to or borrowing (-) from the rest of the world. Precisely the same inferences apply to France’s 2018 spending-income, financial-transaction and balance-sheet data in SNA 2008 format (Appendix 1).

To repeat the essential determination of this section: only when we create new value added — and its corresponding income — is it possible to generate anything we may deem to be surplus profits or, if accumulated, possibly to call surplus capital. In this “classical” case, the necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of surplus profits (and capital) is that net exports NX (exports less imports) less net locally earned income flowing to non-residents NO (locally earned income of non-residents less income of residents earned overseas) is positive. This, in turn, corresponds to the export of capital, which is an increase in net international assets or the IIP. Only then can aggregate corporate profits exceed domestic investment, the definition of surplus profits.

Michał Kalecki (1967 [1971a], pp. 152-3, emphasis added) observed the role of net exports and net lending in his 1967 article “The problem of effective demand with Tugan-Baranovski and Rosa Luxemburg”. Critical of the latter for ignoring imports in her consideration of how, in the development of capitalism as a totality, non-capitalist “external markets” absorb surplus capitalist production, he noted:

…the imported goods absorb purchasing power just like those home-produced, and thus to the extent that exports are offset by imports they do not contribute to the expansion of the markets for national product. Or, to approach it from a different angle, imports, like wages, are costs, and the … disposal of profits is, alongside capitalists’ consumption and investment, solely the export surplus. And in order that this should be possible export of capital is necessary. Only to the extent to which the capitalist system lends to the non-capitalist world (or the latter sells its assets) is it possible to place abroad the surplus of goods unsold at home. Only in this way do “the external markets” solve the contradictions of the world capitalist system.

(iv) Classical case with monopoly surplus profits

To exhaust the logic of the classical case without altering its basic assumptions, it is worthwhile digging a little deeper. Recall that the classical case is intimately entwined with monopoly. Is it possible that monopolies (loosely defined to embrace oligopolies, etc) can, on their own account, register surplus profits and surplus capital and be responsible for a country’s capital exports? If so, again we ask what are the conditions necessary for such a possibility? Recall that this is much the scenario painted by Mandel, as quoted above. It bears repeating for ease of reference:

… a qualitative increase in the concentration and centralization of capital leads to the elimination of price competition from a series of key branches of industry… A trend to regulate (i.e., limit) investment and production in monopolized sectors henceforth prevails, in spite of the existence of monopolistic surplus-profits [“specific forms of surplus-profit originating from obstacles to entry into special branches of production”, the general forms of which are “profits over and above the socially average rate of profit”, pp. 595, 597], so that over-accumulation [“a state in which there is a significant mass of excess capital in the economy, which cannot be invested at the average rate of profit normally expected by owners of capital”, p. 595] leads to a frantic search for new fields of capital investment and hence to a growth of capital exports.

Starting with [3.3] above, we separate monopoly profits Pm and investment Im from non-monopoly profits Pn and investment In. With households and general government in balance, it is easy to arrive at [3.4]:

(P – I) = (0) + (0) + (NX – NO) [3.3]

Pm + Pn + Im + In = (0) + (0) + (NX – NO) [3.3.1]

(Pm – Im) = (In – Pn) + (NX – NO) [3.4]

Rehearsing similar conclusions we reached for the base case, the sum by which Pm exceeds Im — monopoly surplus profits — now depends on the joint “excess spending” efforts of non-monopoly capital plus net lending to the rest of the world. Surplus profits are possible and, insofar as the classical monopoly case may involve the existence of capital exports, it seems more credible. Moreover, as [3.5] below suggests, it is no longer necessary that non-monopoly investment must exceed non-monopoly profits. As long as NX – NO is positive, both Im and In may be less than their profit counterparts.

(Pm – Im) + (Pn – In) = (NX – NO) [3.5]

Note, again, that none of this speaks to the levels of investment and net lending and, therefore, of profits. Again, monopoly capital might make surplus but not super profits, surplus and super profits or, if the signs of the terms in [3.4] were to reverse, super but not surplus profits and neither super nor surplus profits. In any event, the possibility of monopoly surplus profits is dependent on the right-hand side of [3.4] being positive. That is, monopoly surplus profits and surplus capital depend for their existence on other institutional sectors’ excess spending. The implications of this conclusion flow into a consideration of the general case.

(v) General case

It is a short step now to the general case, one that places no restrictions on each of the functional sectors20 of the economy: corporations, households, general government and the rest of the world. From [2] above (repeated here for easy reference) we now have [2.2], and from [3] above (ditto) we now have [3.6]:

P = I + (G – T) + (C+ – H) + (NX – NO) [2]

Pm = Im + (In – Pn) + (G – T) + (C+ – H) + (NX – NO) [2.2]

(P – I) = (G – T) + (C+ – H) + (NX – NO) [3]

(Pm – Im) = (In – Pn) + (G – T) + (C+ – H) + (NX – NO) [3.6]

Let us then simplify matters by substituting for P – I in [3] and Pm – Im in [3.6] the symbols E and E’, both being shorthand for net excess spending by non-corporate and non-monopoly sectors21, respectively. The implications of this shorthand are now easier to see. Excess spending is:

E = (G – T) + (C+ – H) + (NX – NO) = (P – I) [3.7]

E’ = (In – Pn) + (G – T) + (C+ – H) + (NX – NO) = (Pm – Im) [3.8]

The preceding conclusion that the secret to surplus profits lies in spending exceeding income on the right-hand side of the relevant expression holds a fortiori because the case is now general. For surplus profits to exist, net excess spending by households, general government and the rest of the world must be positive. Likewise, the conditions necessary for monopoly surplus profits to exist require that net excess spending by other institutional sectors — households, general government, the rest of the world and non-monopoly sectors of the domestic economy — should be sufficient to allow monopoly profits to be greater than monopoly capital’s investment spending.

Such investment, as we know from [2], determines the level of profits. This is also what the expression [2.2] above tells us about the level of monopoly profits. Again, we should be careful to distinguish level and surplus. For instance, were net “excess” spending by households, general government, the rest of the world and non-monopoly sectors of the domestic economy to be zero or less than zero, monopoly investment spending — regardless of its level — would be greater than monopoly profits. This is to say that it would be solely responsible for monopoly profits existing at all. Nevertheless, no matter how large such investment were, an absence of spending by the other sectors would determine that surplus profits neither existed nor accumulated as surplus capital. This is to say that we should also be careful to distinguish conceptually surplus profits from super profits.

Similarly, we should be wise not to assume an automatic correspondence between capital exports and surplus profits. A negative value for E or E’ — the absence of surplus profits in general and monopoly profits in particular — can correspond to capital exports so long as negative excess spending by general government (budget surplus), households (net saving) and non-monopoly capital (Pn > In) collectively offset NX – NO. The obverse may hold, too, if excess spending by these sectors (in aggregate) exceeds a negative value for NX – NO. That is, it is possible to have surplus profits with capital imports.

Conclusions

Each of the preceding cases has, in its own way, shown both the possibilities for, and the limitations of, the standard arguments, commonly held beliefs and assumptions concerning monopoly capital, super profits, surplus profits, surplus capital, export of capital and imperialism. As their interrogation became more general, the exceptions to, and difficulties with, the standard arguments became more apparent. The pieces of the jigsaw were less capable of depicting fundamental, enduring global economic relationships. Some did not fit at all. This was simply because surplus profits/capital lost any necessary connection to both super profits and capital exports. Grandiloquent theories based on the standard arguments, commonly held beliefs and assumptions are thus overstated, at best.

More importantly, this contribution has exposed flaws in the logic supporting the standard arguments, commonly held beliefs and assumptions. Recall that these begin with the conception that capital (monopoly capital especially) makes surplus/super profits that accumulate as surplus capital. Capital then confronts a problem of declining returns to domestic investment for some reason or other. It is superabundant, febrile and desperate for outlets. Therefore, to absorb its overflowing surpluses, capital takes advantage of capital exports and other external markets (for example, sales efforts to encourage greater household spending, government deficit spending on armaments, roads, etc).

The problem, however, is that this is not at all how things work. This contribution has demonstrated that the excess spending (or otherwise) that corresponds to such external markets — excess spending by non-corporate or non-monopolistic institutional sectors — is the cause of monopoly surplus profits/capital. It is the sine qua non of surplus profits/capital. A brief comparison between the base case, in which surplus profits/capital are not possible, and the general case, in which the other sectors’ net excess spending causes and is equal to surplus profits/capital, shows this conclusively. The level and sign of net excess spending thus determines whether surplus profits/capital are positive or negative, large or small.

This upending or inversion in logic is no mere shift of emphasis. Rather, it exhibits an altogether deeper understanding of how open macroeconomies actually function. This, in turn, will help to extract meaning from world economic data and offer discussions of imperialism the possibility of greater rigour.

Appendix 1

The following illustration of this contribution’s conceptual structure draws on the European Commission, International Monetary Fund, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, United Nations and World Bank’s System of National Accounts, 2008 (SNA 2008) and the International Monetary Fund’s Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual, Sixth Edition (BPM6 2009). These references provide both clarity and a link to the available data. With this in mind, the illustrative table below applies the framework to actual data from France in 2018. For the most part, it uses the SNA 2008 data published by the OECD (see reference codes in the top row and left-hand column of each panel). Appendix 2 approaches the same concepts from the BPM6 perspective.

While the table owes much to the above references, it presents it with subtle differences. In particular, the table’s first panel, which sets out the fundamental relationships, allocates the spending categories so that Y = C+I+G+NX and disposable income categories so that Y=H+P+T+NO. The distribution of Y (income derived from GDP) as disposable income necessarily means that NO represents income to the rest of the world (ROTW), the obverse of our country’s. Hence, in the first panel, the total overseas income NO, which represents the rest of the world in relation to our country (France 2018, in this illustration), has the opposite sign.

The second panel, “Financial assets, liabilities acquired by institutional sector in year”, records France’s total transactions in broad categories of financial instruments. The corporate column shows that it was a net borrower and that its net financial assets fell (i.e. P – I = -€23b). Its other financial transactions, which were much larger, and much larger also than its gross capital investment spending of €341b, involved offsetting of financial asset purchases with corresponding liabilities. Hence, its acquisition of financial assets (€1,496b) fell short of its acquisition of liabilities22 (€1,519b) to the extent of its (negative) surplus profits of -€23b.23 Similarly, compare both the logic and the magnitudes of France’s acquisitions of overseas and total share assets and liabilities (grey highlights in the second and third panels) with data in the first panel. Refer again to the discussion of financial assets and corresponding liabilities in “(iii) Classical case” above.

The second panel of Appendix 1, France’s financial account for 2018, shows that NX – NO is -€1624 and that this is equal to the balance of France’s net borrowing from the rest of the world. From Appendix 2, we understand that NX – NO is, in balance-of-payments language, the sum of the current and capital accounts of the balance of payments. Appendix 2 shows that this sum is equal to the net balance of the financial account of the balance of payments — again, a country’s net lending (+) or net borrowing (–). France in 2018 was a net borrower, while the country depicted in Appendix 2, part of the common numerical example used throughout both the SNA 2008 and the BPM6, the country is a net lender.

Why is it essential to stress these points? Quite simply it is because the financial account balance, net financial transactions, net lending (+) or borrowing (–) and NX – NO are quantitatively equivalent but different perspectives on one and the same concept, namely what economics has traditionally called capital exports or imports (see Appendix 2 for further explanation).

Appendix 2

The following also draws on the European Commission, International Monetary Fund, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, United Nations and World Bank’s System of National Accounts, 2008 (SNA 2008) and the International Monetary Fund’s Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual, Sixth Edition (BPM6 2009).

A country’s net lending (+)/borrowing (–) — its capital exports and imports — corresponds to the balance of the financial account of its annual balance of payments flows. This balance is equal to the sum of the annual current and capital account flows of its balance of payments. In turn, net lending/borrowing (the financial account balance = current plus capital account balances), plus other changes and revaluations, is equal to the change from the start to the end of the year in a country’s international investment position (IIP). The IIP records a country’s stocks of international assets less its stocks of international liabilities. BPM6 Table 2.1 (2009, p. 14), reproduced below, summarises the principal categories and linkages that describe a country’s economic relationships with the rest of the world.25 Note the following:

- BPM6, in drawing up a balance-sheet account of foreign assets and liabilities (the international investment position, IIP), uses the perspective of the domestic economy, “whereas in the SNA it is drawn up from the point of view of the rest of the world” (SNA 2008, p. 257). That is, the SNA treats the rest of the world as if it were, along with corporations, households and institutions that serve them and general government, as a sector (see for example OECD Table 14A. Non-financial accounts by sectors). The difference between the SNA 2008 and BPM6 is that the resultant number will have a different sign. “The international accounts correspond to the rest of the world accounts of the SNA. They differ in that the balance of payments is from the perspective of the resident sectors, whereas national accounts data for the rest of the world are from the perspective of non-residents.” (BPM6 2009, p. 12) For an application of the perspective of the SNA 2008, see Australian System of National Accounts External Balance Sheet, Current prices (ABS 2023, Cat. 5204.0, Table 45).

- BPM6 represents the financial account categories by their function rather than by the nature of the financial instrument involved. Compare the categories in second and third panels of Appendix 1 with the “Financial account (by functional category)” and “International Investment Position” in the figure below. Note also that, regardless of categorisation by function (BPM6) or by instrument (SNA 2008), offshore asset and liability transactions fall under a financial rubric in both balance of payments and national accounting frameworks. BPM6, chapter 7, provides a reconciliation of functional and instrumental classifications (see esp. Table A7.1, p. 290).

Those more familiar with traditional international economics literature might find useful the following rather long terminological clarification:

… the sum of the current and capital account balances can also be … labeled as net lending (+)/net borrowing (–)… That sum is also conceptually equal to net lending (+)/net borrowing (–) from the financial account … The current and capital accounts show nonfinancial transactions, with the balance requiring net lending or net borrowing, while the financial account shows how net lending or borrowing is allocated or financed … In economic literature, “capital account” is often used to refer to what is called the financial account in this Manual and in the SNA. The term “capital account” was also used in the Balance of Payments Manual prior to the fifth edition. The use of the term “capital account” in this Manual is designed to be consistent with the SNA, which distinguishes between capital transactions and financial transactions … The value of net lending/net borrowing in the international accounts is conceptually the same as the aggregate of net lending/net borrowing of the domestic sectors in the SNA. This is because all the resident-to-resident flows cancel out. It is also equal to the opposite of net lending/net borrowing of the rest of the world sector in the SNA. (BPM6, p. 216)

4. In addition to changes in the volume of a country’s IIP balance due to financial account (= current plus capital accounts) transactions, other volume, as well as price, changes will affect the balance (BPM6 2009, Chapter 9). An example of other changes in volume is debt cancellation. Price changes result in the need to revalue both assets and liabilities.

Together with the financial account (= current plus capital accounts), the other changes in financial assets and liabilities explain changes in the IIP. In other words, financial assets and liabilities gain or lose value and appear or disappear as a result of transactions (as recorded in the financial = current and capital accounts), other volume changes, or revaluation. This relationship can be expressed as the following identity: Beginning of period position + Transactions during the period + Other changes in volume during the period + Revaluation during the period: Of which, due to: exchange rate changes and other price changes = End of period position. (BPM6 2009, p. 142)

References

Amsden, A.H. 1987, Imperialism, in The New Palgrave: Marxian Economics, pp. 205-17, from Eatwell, J., M. Milgate and P. Newman eds. 1987, The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, Macmillan, London.

Armstrong, P., A. Glyn and J. Harrison 1991, Capitalism Since 1945, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

____ 1984, Capitalism Since World War II: The Making and Breakup of the Great Boom, Fontana, London.

Baran, P.A. 1957, The Political Economy of Growth, Monthly Review Press, New York.

Baran, P.A. and P.M. Sweezy 1966, Monopoly Capital: An Essay on the American Economic and Social Order, Monthly Review Press, New York.

Courvisanos, J., J. Doughney and A. Millmow eds. (2016), Reclaiming Pluralism: Role of History of Economic Thought in Heterodoxy – Essays in Honour of John E. King, Routledge, London.

Doughney, J. 2016, Problems in Marx’s Theory of the Declining Profit Rate, in Courvisanos, J., J. Doughney and A. Millmow eds., Reclaiming Pluralism: Role of History of Economic Thought in Heterodoxy – Essays in Honour of John E. King, Routledge, London.

—— 2025 forthcoming, Lenin’s Imperialism: A Critical Summary. Victoria University, Melbourne.

Eatwell, J., M. Millgate and P. Newman eds. 1987, The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, Macmillan, London.

EC, IMF, OECD, UN and World Bank 2009, System of National Accounts 2008 (SNA 2008), European Commission, International Monetary Fund, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, United Nations and World Bank, New York.

Harvey, D. 2021, Rate and Mass: Perspectives from the Grundrisse, New Left Review 130, July-August 2021, pp. 73-98.

Hobson, J.A. 1902, Imperialism: A Study, Cosimo Classics edn. 2005, New York.

IMF 2009, Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual (BPM6), International Monetary Fund, Washington DC.

Kalecki, M. 1969 (1954), Theory of Economic Dynamics: An Essay on Cyclical and Long-Run Changes in Capitalist Economy, Augustus M. Kelley, New York.

____ 1971a, Selected Essays on the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy: 1933-1970, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK.

____ 1937 (1954), Entrepreneurial Capital and Investment, in Kalecki 1971a, pp. 105-9.

____ 1942 (1954), The Determinants of Profits, in Kalecki 1971a, pp. 78-92.

____ 1967, The Problem of Effective Demand with Tugan-Baranovski and Rosa Luxemburg, In Kalecki 1971a, pp. 146-55.

____ 1968, The Marxian Equations of Reproduction and Modern Economics, background paper, International Social Science Council and the International Council for Philosophy and Humanistic Studies Symposium, UNESCO, 8–10 May, Social Science Information 6(7), pp. 73-9. Republished in J. Osiatyński ed. 1991, Collected Works of Michał Kalecki: Capitalism: Economic Dynamics, vol. 2, Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp. 459–66.

Keynes, J.M. 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Macmillan, London.

King, J.E. 2015, Advanced Introduction to Post Keynesian Economics, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham UK.

Lenin, V.I. 1916 (1976), Imperialism, The Highest Stage of Capitalism, in V.I. Lenin: Selected Works in Three Volumes, volume 1, Progress Publishers, Moscow, pp. 641-731.

____ 1920, Preface to the French and German editions of Imperialism, The Highest Stage of Capitalism, in V.I. Lenin: Selected Works in Three Volumes, volume 1, Progress Publishers, Moscow, pp. 636-40.

Mandel, E. 1975, Late Capitalism, trans. Joris de Bres New Left Books, London.

Rowthorn, R. 1976, Late Capitalism, New Left Review, 1/98, July-August 1976, pp. 59-83.

van de Ven, P. and D. Fano eds. 2017, Understanding Financial Accounts, OECD Publishing, Paris, at https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264281288-en.

Stern, R. and T. Cheng 2023, Transcendental Arguments, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2023 Edition), E. Zalta and U. Nodelman eds., https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2023/entries/transcendental-arguments/.

Sweezy, P.M. 1942, The Theory of Capitalist Development, Monthly Review Press, New York.

____ 1987a, Paul Alexander Baran, in Eatwell, J., M. Millgate and P. Newman eds. 1987, pp. 50-2.

____ 1987b, Monopoly Capitalism, in Eatwell, J., M. Millgate and P. Newman eds. 1987, pp. 297-303.

- 1

The ‘term “late capitalism” in no way suggests that capitalism has changed in essence, rendering the analytic findings of Marx’s Capital and Lenin’s Imperialism [1916] out of date’ (Mandel 1975, p. 9).

- 2

W.B. Yeats, ‘The Second Coming’, first published 1920, The Dial.

- 3

‘Problems in Marx’s Theory of the Declining Profit Rate’ (Doughney 2016, pp. 120-36).

- 4

‘Lenin’s Imperialism: A Critical Summary of the Economic Arguments’ (Doughney 2025). https://links.org.au/lenins-imperialism-critical-survey-economic-arguments Marx’s use of ‘surplus profit’ and ‘surplus capital’ shall be the subject of a separate 2025 contribution.

- 5

That is, incomes after accounting for net primary and secondary income transfers between institutional sectors.

- 6

That is, before deducting depreciation expenses.

- 7

Relevant variables in this paragraph include net capital transfers and net acquisitions of non-produced non-financial assets (SNA 2008, pp. 197, 212-18; BPM 2009, pp. 9, 216-21).

- 8

‘[The SNA 2008] has been produced and is released under the auspices of the United Nations, the European Commission, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank Group. It represents an update, mandated by the United Nations Statistical Commission in 2003, of the System of National Accounts, 1993, which was produced under the joint responsibility of the same five organizations.’ (SNA 2008, p. iii) Figure 1 relies on the OECD’s Table 14A, at https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SNA_TABLE14A.

- 9

To frame the discussion in this way — in the form of answers to “transcendental” questions/arguments (for example, Stern and Cheng 2023) — should help in clarifying the economic logic. Such clarification has become all the more necessary because the subject can be needlessly complicated by tortured arguments and numerical illustrations (see e.g. Mandel 1975, pp. 531ff). As Rowthorn (1976, p. 60) has noted, Late Capitalism (Mandel 1975) “is often eclectic and its arguments are at times confused or unnecessarily abstruse”.

- 10

Kalecki (1942 [1971a], pp. 78-9; 1954 [1969], pp. 45-7; see also Kalecki 1968). Here, Kalecki’s workers’ consumption and capitalists’ consumption fold into the single category of household consumption. What we lose in class insight we pick up in tractability, namely the ability to use the readily available national-accounting framework and data. We also avoid the vexed question of determining the proportions of wage-earners and the self-employed that fall into the working class. Is the employed CEO on a salary of $1m+ a year working class? Is the local house-painter with an apprentice whose business earns $75,000 a year a capitalist, merely petty bourgeois or a worker with her own tools who is generously teaching her skills to a lad in order to hand on the business and then retire on the age pension?

- 11

“Because of the important relationship between external and domestic economic developments, the Manual was revised in parallel with the update of the System of National Accounts 2008. To support consistency and interlinkages among different macroeconomic statistics, this edition of the Manual deepens the harmonization with the System of National Accounts and the IMF’s [International Monetary Fund] manuals on government finance and on monetary and financial statistics.” (BPM6 2009, p. ix)

- 12

That is, in an economic sense, Ricardian and pre-Kaleckian, pre-Keynesian.

- 13

According to King (2015, p. 11) this led [Kalecki] “to the famous aphorism (which accurately reflects his views, but which no one has been able to find in his published work) that ‘workers spend what they get; capitalists get what they spend’.” Note also that investment spending is macroeconomically more active, whereas consumption is relatively more passive (Armstrong, Glyn and Harrison (1991, p. 124; see also 1984, p. 177): “Regardless of their importance in sustaining accumulation by providing a growing market for consumer goods, wages must be regarded as a basically passive element in the process of realization. The development of wages is largely a product of accumulation itself … Workers’ spending as a whole provides the demand which realizes the profits of capitalists producing consumer goods. But the pay of their employees is an expense which reduces profits, not a source of demand which realizes them. Only the spending of workers employed elsewhere realizes profits in the consumer goods industries. These workers will only be employed if there is demand for the products they make — for export, from the government or from the employers themselves. So the realization of all the potential profits ultimately depends on sufficient spending by the employers (on investment or consumption), the government or by those purchasing exports.” Keynes’s (1936, p. 317, emphasis added) reflection on Hobson’s wrongheaded emphasis on underconsumption, at the logical expense of investment, makes a similar point: “Mr. Hobson laid too much emphasis (especially in his later books) on underconsumption leading to over-investment, in the sense of unprofitable investment, instead of explaining that a relatively weak propensity to consume helps to cause unemployment by requiring and not receiving the accompaniment of a compensating volume of new investment.”

- 14

See Kalecki (1937 [1971a], pp. 106-9; 1937 [1954], pp. 92-5).

- 15

Recall that we are talking about gross disposable profits, which is to say profits before depreciation but after interest, dividends, taxes and rent. Gross disposable profits include depreciation expenses, whereas net disposable profits deduct them. See n. 16.

- 16

Paul Sweezy (1987a, pp. 50-2), for example, noted about the school of thought that he and Paul Baran had initiated: “The economic analysis of Monopoly Capital [1966] is a development and systematization of ideas already contained in [Baran’s] the Political Economy of Growth [1957] and Paul Sweezy’s The Theory of Capitalist Development (1942). The central theme is that in a mature capitalist economy dominated by a handful of giant corporations the potential for capital accumulation far exceeds the profitable investment opportunities provided by the normal modus operandi of the private enterprise system. This results in a deepening tendency to stagnation which, if the system is to survive, must be continuously and increasingly counteracted by internal and external factors.” See also Sweezy (1987b).

- 17

I ask readers to persevere with this terminology. Footnote 21 below shall explain why.

- 18

See Appendices 1 and 2 for more detailed numerical examples. Appendix 1 illustrates net borrowing by France in 2018 (capital imports). Appendix 2 illustrates net lending (capital exports).

- 19

Those who have wondered why ‘capital’ was in scare quotes can now have an answer. The corporate example here is the same in principle as the case of a Swiss tourist to Britain who wants to hold a handbag full of pounds or to open an account in a British bank.

- 20

The institutional units or sectors responsible for specific kinds of spending. See “Identities, causality and definitions” above.

- 21

In Rosa Luxemburg’s coinage, we might also refer to the E terms as excess spending by net “external markets” and those markets as our functional institutional sectors (see e.g. Kalecki 1967 [1971a]). In the lexicon of standard economics, the income-spending gap — assuming it to be greater than zero — is called “saving”. The case we have been considering, in which surplus profits exist, would be “dissaving”. This terminology still exists, despite the fact that, the paradox of thrift notwithstanding, aggregate saving is the cause of aggregate spending’s cause. Hence, I have opted to flip the emphasis.

- 22

Including statistical discrepancy. ‘Often, the compilation process for the financial accounts and balance sheets is sufficiently separate from the rest of the accounts that the figures for net lending or net borrowing derived from each are different in practice even though they are conceptually the same.’ (SNA 2008, p. 397) Similarly, statistical discrepancies exist between conceptually equivalent data collected for SNA 2008 purposes and those collected for BPM6 purposes.

- 23

The changes in the third panel of Appendix 1 do not correspond to -€23b because each item’s accumulated total is subject to revaluation each year according to price changes, including changes in exchange rates, and other volume changes, such as cancellation of debt. See also Appendix 2.

- 24

NB. In Figure 1, France has a net exports deficit of €24b but a net overseas income surplus of €8b. The “Overseas” (or Rest of the World) column shows this as -€8 because NO records income going to the overseas sector. Hence, NX -NO = -€24b - -€8b = -€16. See the notes to the first panel for additional detail.

- 25

See BPM6 (2009, pp. 14, 18-28, 301-12) for detail. See also SNA (2008, pp. 330, 488-95) and van de Ven, P. and D. Fano eds. (2017, p. Table 7.1).