Pele leaves us but his magic will never die

First published at Anti*Capitalist Resistance.

Slavery in Brazil had only ended fifty-two years before his birth, and he was poor enough to work as a shoe shine boy, but his talent as a football player made his name known all over the world. Kids like me in Britain grew up wanting to be Pelé in our knockabout games in the park. Pelé (born Edson Arantes do Nascimento) and Brazilian football seemed to be a different game from the one we saw here, with hard midfielders and long balls up to the big centre forward. The obituaries mention how he was kicked out of the 1966 World Cup because of the laxer refereeing at that time. The England camp or press did not make a great deal of fuss about it at the time. Brazil were a potential threat, and English players like Nobby Styles benefited from that refereeing.

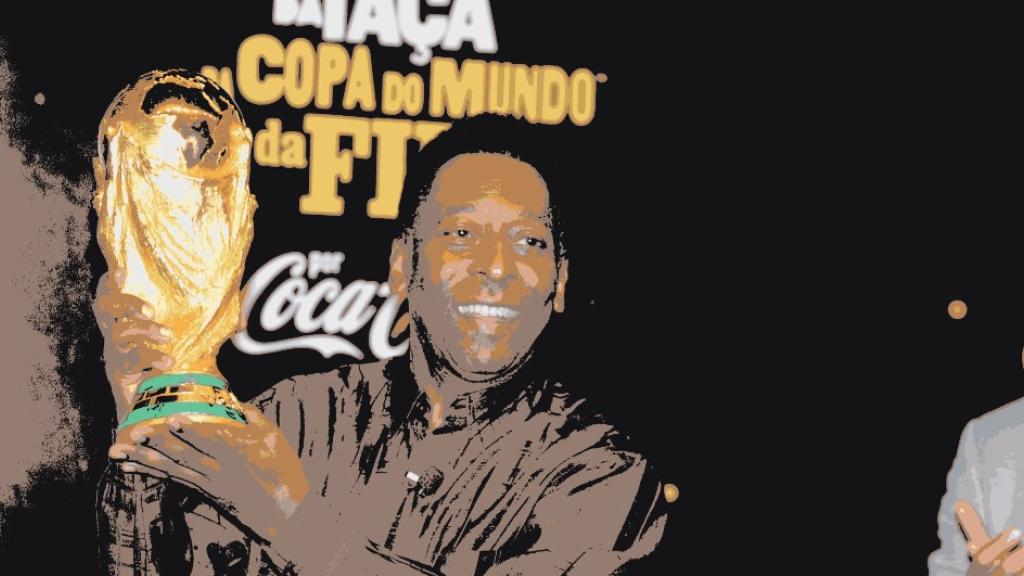

Even after his retirement, he remained one of the institutional representatives of the global game. Old black-and-white footage and the first colour images of the magnificent 1970 Brazil World Cup winning team kept his aura alive for people who were too young to know him when he was playing. Was he the greatest of all time? He is the only footballer to have won three World Cups and scored the most goals. Players could rough him up much more easily than today. Comparing different eras is always difficult, but he is up there with Diego Maradona and today’s Lionel Messi.

Yesterday he passed away, and the world’s media are reflecting on his life. We have lots of information, some insightful articles and wonderful re-runs of his greatest moments.

However, it is framed by an overall ideology where sport is an important part of the capitalist spectacle. The fact that it is getting so much attention from the media right now, to the point where it might be overshadowing more important stories like the Russian missile attack on Ukrainian cities, shows how important it is. This spectacle is a narrative where class struggle, exploitation, and structural racial oppression are largely absent. It is a spectacle our rulers want us to embrace and help reproduce in the way we tell its stories to each other. They need passive consumers, not critical citizens or mass organisers.

Pelé is presented as the triumph of football as an institution that allowed black and poor people to rise to the top. It is an ideology similar to the one that says anybody can become president or prime minister.

The reality for Black footballers in Britain in the 1970s was very different. Fans threw bananas at them on the pitch and made monkey chants when they touched the ball. It is hard for people to understand this today when there is a far greater proportion of Black footballers in the top leagues than the proportion of Black people in the population. For some decades, myths abounded about Black footballers having the wrong attitude or not being up to it when they had to play in cold conditions at Stoke City. There was racist banter in the changing rooms, and many managers were prejudiced.

Like the success achieved by Black people in the cultural industries, this phenomenon is presented as a sign that the system is working, that we have moved on from the bad old days, and that there really are equal opportunities. The Labour Party largely shares this view of the world although it proposes policies that may remove some of the obstacles to opportunities. Even if there is better mobility for individuals, the overall system remains unequal and exploitative. Changing a few faces on the rungs of the ladder does not alter the latter one bit.

It is true that going to the right schools and having the right accent does not help you get picked up by a Premier League scout. However, in this competitive capitalist world, for every Black or working class kid who ends up earning millions as a footballer, there are thousands who go through the system of youth football and academies but end up not making it. Football is very hierarchical, and the money made by the business side of the game isn’t really spread around to encourage more people to play and improve public health.

Even today, after the undeniable progress of Black footballers in the British game, there are very few British-born Black coaches or managers, let alone anyone in key administrative positions in the game. Just being average or mediocre is no barrier to getting plum jobs in law, finance, or management if you are white and go to the right schools and universities. As Lenny Henry has pointed out, even in the cultural industries, certain sectors considered higher culture, like theatre or classical music, are not so accessible to Black or ethnic minority people.

Indeed, it is hardly surprising that Black communities have resisted attempts in some areas to turn their local schools into sporting or performing arts academies. They understand how Black success in sports or music is to be welcomed, but they want their kids to excel in all walks of life. Being great at sports or singing can even reproduce racist notions of Black people as “minstrels” or as being physically strong but not being able to have higher intellectual or management skills. This was the ideology of the slave owner or colonialist.

There is progress and success for a small number of Black people, but it does not deliver progress for all Black or working class people. Pelé’s godlike status in Brazil has not significantly altered the life chances of Black Brazilians, much less the situation of indigenous Amazon Indians. Unlike another great champion, Sócrates, who supported Lula’s PT (Workers Party) in its early, more radical phase, Pelé never supported a particular party but tended to adapt to whoever was in power. He carried out roles for the Brazilian government, the UN, and FIFA, as well as for Mastercard and Pepsi. He needed lucrative work to recover from losing several fortunes. As the first global football media star, he was the key factor in (re)launching professional soccer in the USA.

You cannot demand every successful Black sportsperson take the courageous stands of Black sprinter Tommie Smith in 1968, Muhammed Ali, or Michael Kaepernick. Their protests drew torrents of abuse from the media and cost their careers dearly. But Pelé never used his status, even partially, in such a politically progressive way.

Marx was right when he said in The Communist Manifesto that capital would become truly global and take over the production of all goods and services that people could think of. Everything would become a commodity, and pre-capitalist, cooperative, or feudal forms would disappear. Part of this process was the concentration of capital into bigger and bigger transnational companies.

Football as a commercial activity is an example of this process. Qatar is a centre of transnational capitalism; its funds are integrated into the circuits of European and US capital. This enables it to put on a World Cup without any local football culture. Qatar also owns the Paris St. Germain football club and its star players, Messi and Mbappe, who starred in a final watched by 3.5 billion people. There is not a better example of how the transnational capitalist system works today.

If Pelé was playing in this era, it would be very unlikely that he would have stayed at his club, Santos, and like most of the Brazilian team, he would be playing for elite clubs like Real Madrid or Manchester United. Top footballers, like migrant workers generally, are part of a globalised labour force. There is almost a neo-colonial aspect to European football today as it drains the best footballers from Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The French clubs and their FA have scoured their former colonies for young players. Many obviously do not make it and are left without much support.

Pelé once said that he thought an African team would win the World Cup by the year 2000. There is a picture from the recent final during the penalty shoot-out when you see the French players all lined up. Nearly everyone is of African heritage. An African nation may not have won it, but second- and first-generation African or Afro-Caribbean players form one of the largest ethnic groups among the top teams.

The huge salaries that top professional footballers make also reflect how capitalism works. The actual contribution the commodity or labour makes to society is secondary to how profitable the market makes it. Top footballers are scarce, so like any other commodity, the price the capitalist has to pay for their labour is high. On the other hand, the fruits of that labour can be very profitable through the TV rights, tickets, and sponsorship deals that you consequently own. State regulations have allowed cartels or monopolies to control TV rights, and this has enabled the boom in profits in this sector.

Criticism of footballers, who usually come from working class backgrounds, is often unbalanced and mixed up with snobbish ideology about these young men being flashy and not knowing how to manage their money. It is never linked to the systematic inequality of salaries in our society. Bankers, top accountants, PR, and advertising people, for example, earn big salaries, and their careers last a lot longer. A broken leg is not much of a problem for them. As socialists, we would argue for a totally different system of remuneration where a nurse’s labour is valued as much as that of a banker. Footballers’ value would be assessed in this context.

Pelé’s artistry is nevertheless part of the best of humanity and deservedly provokes awe and delight for millions of people. The aesthetics of football can justly be compared to an opera aria—a passage that moves you in a great novel or great stage performance. Such prowess and magic would still happen without the grotesque distortions of the capitalist reproduction of football as a sport. His genius, like great art, transcends politics and economic systems. Pelé RIP.