Socialist politics and revolutionary compromise

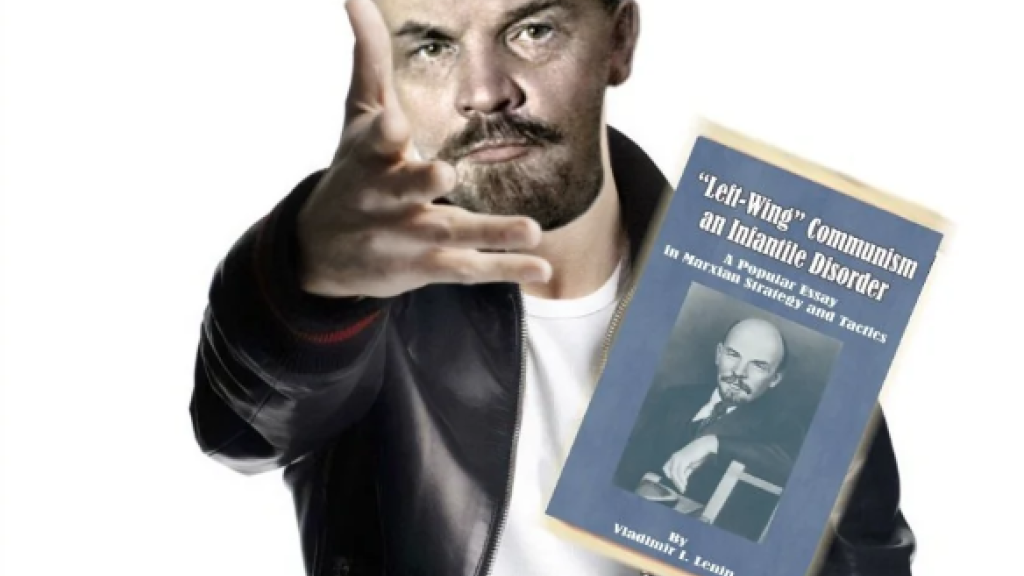

In “On Compromises”, Vladimir Lenin (1917) said: “The term compromise in politics implies the surrender of certain demands, the renunciation of part of one’s demands, by agreement with another party.” In thinking about any compromise, Lenin (1920) wrote in “Left-wing Communism”: An Infantile Disorder, “the greatest efforts are necessary for a proper assessment of the actual character of this or that ‘compromise’.”

In this article, I will discuss types of compromises and why they are necessary and possible. As fascist movements get stronger, the oppression of workers and petty producers from religious or racial minorities intensifies, and attacks on people’s living standards continue, the question of revolutionary compromise by socialist organisations and groups assumes greater urgency.

Types of compromise

There are different types of compromises. For example, compromises can be forced or voluntary. Compromises are forced when they are caused by objective political-economic circumstances but the devotion to class struggle is not diminished. Voluntary compromises are those caused by the actions of working-class traitors.

Lenin eloquently explained the difference:

… between a compromise enforced by objective conditions (such as lack of strike funds, no outside support, starvation and exhaustion) — a compromise which in no way minimises the revolutionary devotion and readiness to carry on the struggle on the part of the workers who have agreed to such a compromise — and, on the other hand, a compromise by traitors who try to ascribe to objective causes their self-interest …their cowardice, desire to toady to the capitalists, and readiness to yield to intimidation, sometimes to persuasion, sometimes to sops, and sometimes to flattery from the capitalists. (Lenin, 1920)

Voluntary compromises cannot be allowed by the Marxist left (henceforward, left) but compromises imposed by objective conditions can be, under certain conditions.

Furthermore, compromises can be made with a) the main class enemy (the bourgeoisie) or b) with one’s “nearest adversaries” (for example, petty-bourgeois-democratic parties). Another group with which compromises are necessary and possible are non-revolutionary left groups.

Compromises can also be made in economic struggle (such as trade union fights) or in political struggle (more on this below). Compromises in economic struggle can be objective or voluntary, as can compromises in political struggle. Discussing compromises in political struggle, Lenin (1920) says:

In politics, where it is sometimes a matter of extremely complex relations … between classes and parties, very many cases will arise that will be much more difficult than the question of a legitimate “compromise” in a strike or a treacherous “compromise” by a strike-breaker, treacherous leader, etc.

Necessity and possibility of revolutionary compromise in political struggle

Here I want to focus on compromise in politics. In the course of the struggle to transcend capitalist society and establish a new genuinely democratic society, circumstances force the proletariat to make compromises in the political sphere. Arguing against the Blanquist communards, Friedrich Engels said it was a mistake to believe that “we want to attain our goal without stopping at intermediate stations, without any compromises, which only postpone the day of victory and prolong the period of slavery.” (quoted in Lenin, 1920)

Lenin was scathing in his criticisms of German Communists who thought “All compromise with other parties ... any policy of manoeuvring and compromise must be emphatically rejected.” (ibid.) To launch class struggle, which is protracted and complex, against the bourgeoisie, nationally and globally, and “renounce in advance any change of tack, or any utilisation of a conflict of interests (even if temporary) among one’s enemies, or any conciliation or compromise with possible allies (even if they are temporary, unstable, vacillating or conditional allies) — is that not ridiculous in the extreme?” (ibid.)

In so far as all bourgeois parties support capitalists, they are the same class enemy for the left. But these parties support — and represent — the ruling classes in different ways. First, different parties represent different interests of the ruling class (with its multiple fractions). Second, these parties, mainly to remain electorally competitive and to gain votes, represent the interests of different fractions differently, and in ways that are to a certain extent mutually conflictual. Some of these ways may partially overlap with the left’s agenda. Some non-socialist parties may be more secular-minded than others. Some may be slightly more pro-poor, pro-worker or pro-peasant than others. Some may support state-funded social services or state interventions to address the climate crisis more than others. Some may support national economic and political sovereignty or may be against the remnants of pre-capitalist relations more than others. None of these are socialist measures but all can make a socialist movement stronger.

Both these facts constitute objective reasons why temporary compromises by left are possible:

The more powerful enemy can be vanquished … by the most thorough, careful, attentive, skilful and obligatory use of any, even the smallest, rift between the enemies…, any conflict of interests among … the various groups or types of bourgeoisie … (Lenin, 1920; italics added)

In fact, the entire history of the socialist movement, “both before and after the October Revolution, is full of instances of changes of tack, conciliatory tactics and compromises with other parties, including bourgeois parties!” (Lenin, 1920)

To vanquish the powerful class enemy, the left may also have to make compromises with small-scale proprietors who exist in large numbers and are exploited by capital, but who vacillate between pro-capitalist parties and the proletarian movement, which fights for the socialisation of means of production. The left has to take “advantage of any, even the smallest, opportunity of winning a mass ally, even though this ally is temporary, vacillating, unstable, unreliable and conditional.” (Lenin, 1920; italics added)

Regarding the possibility and necessity of compromises within the socialist movement, we need to consider the nature of the working class. The working class is potentially the most revolutionary agent. There is no Marxist party/movement without this class. No anti-capitalist revolution is possible without this class (or a substitute for this class and its organisation). This is the only class whose interests most consistently lie in a successful struggle for both democracy and socialism.

Yet, its progressive and revolutionary nature is a potential. The working class as it actually exists falls short, ideologically and politically. This class is deeply politically divided in terms of levels of class consciousness and political preparedness. There are objective reasons for such a situation.

In capitalism, the proletariat is inevitably surrounded by a large number of groups that are:

... intermediate between the proletarian and the semi-proletarian (who earns his livelihood in part by the sale of his labour-power), between the semi-proletarian and the small peasant (and petty artisan, handicraft worker and small master in general), between the small peasant and the middle peasant, and so on. (Lenin, 1920)

The proletariat’s consciousness is shaped by ideas and interests of non-proletarian classes. It is shaped by the ways in which capitalism itself operates on the basis of competition, individualism, commodity fetishism, etc.

Some sections of the proletariat may be bribed by the capitalist class in return for their support for capitalism and imperialism. The proletariat is inevitably “divided into more developed and less developed strata” and “divided according to territorial origin, trade, sometimes according to religion, and so on” (Lenin, 1920; italics added). The fact that different groups of the world proletariat have different levels of class consciousness, histories and experiences is a reason why different socialist individuals, groups and organisations have different ideas about how capitalism works and how to fight it. Some are more revolutionary than others.

The fact that the working class exists but lacks unity and class-consciousness constitutes an objective reason why temporary compromises are necessary within the proletarian movement (for example among various socialist groups). Lenin spoke of:

…the absolute necessity, for the Communist Party, the vanguard of the proletariat, its class-conscious section, to resort to changes of tack, to conciliation and compromises with the various groups of proletarians, with the various parties of the workers and small masters. (Lenin, 1920)

Echoing Lenin’s point that the fight against capitalism requires temporary agreements and a degree of principled unity, Leon Trotsky (1933) wrote:

No successes would be possible without temporary agreements, for the sake of fulfilling immediate tasks, among various sections, organisations, and groups of the proletariat. Strikes, trade unions, journals, parliamentary elections, street demonstrations, demand that the split be bridged in practice from time to time as the need arises; that is, they demand an ad hoc united front, even if it does not always take on the form of one. In the first stages of a movement, unity arises episodically and spontaneously from below, but when the masses are accustomed to fighting through their organisations, unity must also be established at the top.

So, temporary compromises in, for example, the political sphere (such as in elections) are objectively necessary because, at a given juncture, the working masses might be divided and not class conscious (enough), and, concomitantly, the left can be relatively weak. Compromises can also be possible because there are conflicts of interests within the economic and political elites.

The point of political compromise is not to arrive at and settle for a capitalist society that is more or less democratic or more or less egalitarian, and just needs to be managed by left forces for an indefinite time period. The compromise in question here is revolutionary compromise (compromise as a part of, and with the purpose of, advancing long-term goals of class struggle). It is a compromise that is temporarily necessitated by the force of circumstances relative to the strength of the left forces, in order to advance the long-term revolutionary goal of transcending capitalism, and not to help sustain a capitalism sans fascistic tendencies.

Given the significance of temporary revolutionary compromises — compromises with bourgeois and petty bourgeois parties and reformist socialist organisations, etc — Lenin (1920) warned that those who do not understand the need for temporary compromises “reveal a failure to understand even the smallest grain of Marxism, of modern scientific socialism in general.” (ibid.; italics added) He emphasises:

Those who have not proved in practice, over a fairly considerable period of time and in fairly varied political situations, their ability to apply this truth [the truth about the need for political compromise] in practice have not yet learned to help the revolutionary class in its struggle to emancipate all toiling humanity from the exploiters.

Lenin added:

The task of a truly revolutionary party is not to declare that it is impossible to renounce all compromises, but to be able, through all compromises, when they are unavoidable, to remain true to its principles, to its class, to its revolutionary purpose, to its task of paving the way for revolution and educating the mass of the people for victory in the revolution. (Lenin, 1917)1

The development of a socialist movement requires engaging in day-to-day struggles against capitalism and its consequences. Doing so might require fighting alongside not-so-revolutionary groups and making temporary compromises with them. This may require a united front approach. The principle of a united front form of struggle “is imposed by the dialectics of the class struggle” (Trotsky, 1933). One aspect of this dialectics is the fact that the proletariat is deeply divided in terms of concrete needs and everyday economic demands, as well as level of consciousness. That means different sections of the proletariat may be represented by more or less revolutionary organisations.

Conclusion

In line with Lenin’s theory, it is possible to argue that compromises in the electoral/political sphere that pose ideological and political risks (of subordinating workers and peasants to bourgeois forces) are justified only when the following criteria are met, making the temporary agreement highly conditional.

First, compromises are unavoidable or forced by conditions (for example, the left is weak relative to, say, fascistic forces, so it needs allies in some cases). Compromises cannot be due to left leaders’ “cowardice, desire to toady to the capitalists, and readiness to yield to intimidation, sometimes to persuasion, sometimes to sops, and sometimes to flattery from the capitalists.” (Lenin, 1920)

Second, compromises must ultimately contribute to the political project of raising the level of mass consciousness and advancing the goal of the communist struggle against capitalism’s adverse consequences for the masses and capitalist class relations. Lenin said tactics of compromises are applied only “to raise — not lower — the general level of proletarian class-consciousness, revolutionary spirit, and ability to fight and win.” (Lenin, 1920)

Third, left forces must maintain their organisational and ideological independence from non-left parties and movements.

Fourth, the left must always maintain the right to criticise and politically mobilise against its temporary allies when their policies attack the living conditions of ordinary people.

Fifth, the left’s dominant focus must remain on extra-parliamentary mobilisation and not electoral battles, which may involve temporary tactical understanding with non-left forces. The point of temporary agreement is not to confine class struggle to the parliamentary/electoral sphere.

For Marxism — the foundation of which Marx and Engels laid and Lenin and Trotsky, among others, strengthened — revolution requires united action. Marxism recognises that sectarianism is counter-productive.2 It recognises that unity is “a good thing so long as it is possible,” but not, of course, at the expense of the fundamental principles or long-term goal of developing socialist consciousness (Engels, 1882). A non-sectarian revolutionary politics requires working with allies — especially, when fascistic political movements are everywhere and when people’s democratic and social rights are attacked by all sections of the capitalist class.

Socialists ignore this warning at their own peril:

One of the biggest and most dangerous mistakes made by Communists … is the idea that a revolution can be made by revolutionaries alone. On the contrary, to be successful, all serious revolutionary work [must be guided by] … the idea that revolutionaries are capable of playing the part only of the vanguard of the truly virile and advanced class… A vanguard performs its task as vanguard only when it is able to avoid being isolated from the mass of the people it leads and is able really to lead the whole mass forward. Without an alliance with non-Communists in the most diverse spheres of activity there can be no question of any successful communist construction. (Lenin, 1922)

Raju J Das is Professor at the Faculty of Environmental and Urban Research, York University, Toronto. https://rajudas.info.yorku.ca

References

Das, R. 2019. “Politics of Marx as Non-sectarian Revolutionary Class Politics: An Interpretation in the Context of the 20th and 21st Centuries.” Class, Race and Corporate Power, 7(1).

Engels, F. 1882. Letter to Bebel. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1882/letters/82_10_28.htm

Lenin, V. 1917. On Compromises. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/sep/03.htm

Lenin, V. 1920. “Left-wing Communism”: An Infantile Disorder https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1920/lwc/ch06.htm

Lenin, V. 2022. On the Significance of Militant Materialism. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1922/mar/12.htm

Trotsky, L. 1933. The German Catastrophe. https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/germany/1933/330528.htm

- 1

“To agree, for instance, to participate in the Third and Fourth Dumas was a compromise, a temporary renunciation of revolutionary demands. But this was a compromise absolutely forced upon us, for the balance of forces made it impossible for us for the time being to conduct a mass revolutionary struggle, and in order to prepare this struggle over a long period we had to be able to work even from inside such a ‘pigsty’.” (Lenin, 1917).

- 2

Note that it is not sectarian if a Marxist organisation refuses to join a bourgeois/reformist group/party organisationally, or if a democratically-functioning Marxist leadership drives away reformist people from its organisation (Das, 2019).