We live in a world of growing imperialist rivalries

First published at Jacobin.

The international political and economic order is rapidly changing. The United States and Europe increasingly resort to protectionism, industrial policy, and the so-called friend-shoring of supply chains to source from allies only. The US establishment is all but openly admitting its need to put a check on China’s economic and geopolitical rise. Meanwhile, Russia has joined the club of isolated and sanctioned pariah states. However, the size of its economy, and its role as one of the world’s largest energy exporters, changes the nature of the anti-Western coalition, also affecting the US-China rivalry. And the arbitrary nature of “the rules-based order” is being amply exposed in Gaza.

Faced with these global imperialist shifts, the Left needs an analysis that can guide both a progressive foreign policy and a vision of radical change at home. Here, my aim is to define the contours of the current imperialist realignment and call on the Left to study these international processes, particularly in the semiperiphery, from a critical perspective.

US-China rivalry

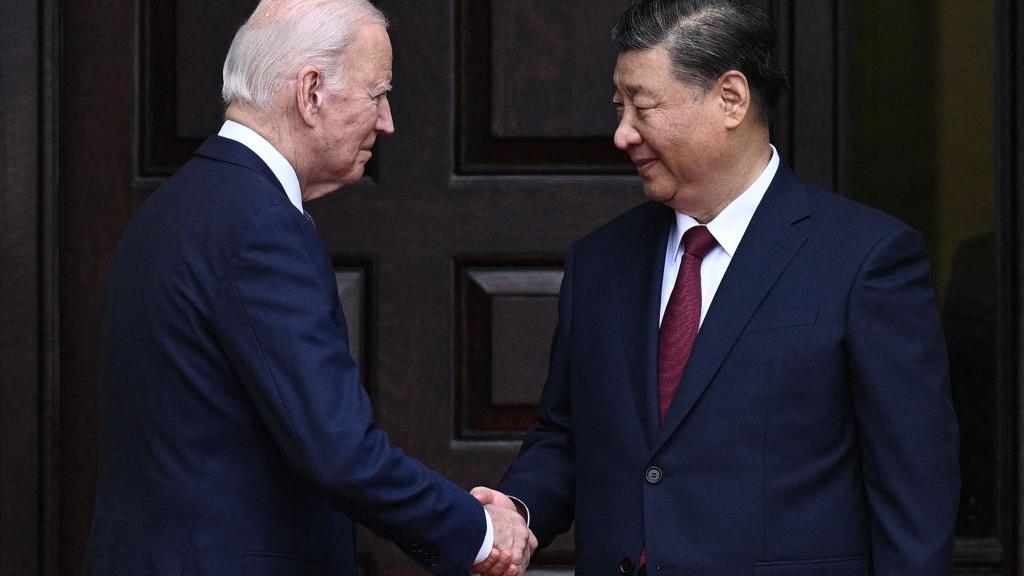

For the last several years, the US-China relationship has progressively deteriorated, with hostile rhetoric and moves like House of Representatives speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in 2022. However, in recent months, US and Chinese leaders have both resorted to conciliatory language, emphasizing that neither of them wants conflict or a new Cold War. Both Joe Biden and Xi Jinping try to defuse the situation rhetorically, yet neither of them sounds convincing.

Part of the problem is the rhetoric itself. In April 2023, US treasury secretary Janet Yellen reiterated that confrontation between the two countries is not inevitable and that the United States does not seek to prevent China’s economic rise. However, she went on to clarify: “China’s economic growth need not be incompatible with U.S. economic leadership.” This statement echoes the apparent consensus in US ruling circles that having both economic and geopolitical parity between the United States and China is unacceptable. In a recent essay for Foreign Affairs aptly named “What America Wants From China,” Ryan Hass, a former member of the National Security Council, expresses a similar logic. He claims that the United States should try to include China in the international system, convincing Beijing that “the best path to the realization of its national ambitions would be to operate within existing rules and norms.” However, like Yellen, Hass stresses the need to preserve US economic leadership by sustaining “an overall edge over China in technological innovation, particularly in fields with national security implications.”

Both Yellen and Hass try to square the circle of simultaneously convincing China that that the US-centric system is its best bet in terms of economic development and calling on the United States to maintain an economic lead over China — by actively preventing Beijing from developing cutting-edge technologies if necessary. As Adam Tooze points out, “It is hard to see how [Yellen’s] vision, in which the United States arrogates to itself the right to define which trajectory of Chinese economic growth is and is not acceptable, can possibly be a basis for peace.” Indeed, the United States seems to claim that right in practice, most notably, by introducing broad sanctions against the Chinese semiconductor industry. When Huawei unveiled a new 5G phone complete with a seven-nanometer processor produced domestically despite US sanctions, US commerce secretary Gina Raimondo admitted that she was “upset” and that the “only good news” was that there was no evidence China could produce such chips at scale. She added that the United States needed “different tools” to enforce sanctions. These remarks make perfect sense in the context of the ongoing US policy to limit the development of the Chinese semiconductor industry. They make no sense, however, in view of Yellen’s declaration that “these national security actions are not designed for us to gain a competitive economic advantage, or stifle China’s economic and technological modernization.” Given the centrality of the chip industry to the overall economic development, what else are these actions designed for?

Both sides, especially with Biden at the helm in the United States, make an effort to avoid the aggressive “othering” that has been so prevalent in US-Russian relations. A recent report by RAND Corporation, the main think tank of the US national security establishment, urges moves to avoid misunderstanding Chinese intentions and motives through open dialogue and careful diplomacy. Both the US and China leaderships are mindful of the importance of their relationship to the fate of the world, and neither is actively looking for a fight. Yet the spiral of deterioration of the bilateral ties seems unstoppable, with trade wars, rising export and investment controls, mutual securitization of the various parts of the relationship (such as scientific cooperation), and geopolitical flash points including Taiwan and the South China Sea. Could the United States and China avoid spiraling confrontation by adopting a less offensive posture and changing their strategic orientations, e.g., if the United States abandons the goal of strategic and economic primacy at all costs?

Marxist theories of imperialism — both the classic ones advanced by Rosa Luxemburg and Vladimir Lenin and the modern ones, such as David Harvey’s theory of the “new imperialism” — link aggressive foreign policy to the contradictions of capital accumulation. In this view, interimperialist rivalries have a structural cause that is irreducible to messianic imperialist ideologies or the search for security that creates insecurities for other states, as in the realist accounts of the “security dilemma.” According to the Marxist interpretation, domestic industrial overcapacity and the overaccumulation of capital compel the national bourgeoisie to seek external expansion. In this endeavor, capital enlists the help of the state to protect its overseas investments, markets, and trade routes. The clash between nation-based capitals over markets and profitable outlets for investment leads to interimperialist rivalries. Some argue that such conflicts are obsolete due to the emergence of the transnational capitalist class (TCC), with the nascent “transnational state” to serve its interests. However, the TCC thesis looks increasingly problematic from an empirical standpoint. Research shows that global capitalist networks remain highly regionalized and uneven, with limited interlocking between the Global North and other countries, including China. The concept of the “transnational state” seems even more far-fetched, with rising militarization, protectionism, trade wars, and conflicting geopolitical visions such as the US “Pivot to Asia” versus the Chinese “Belt and Road Initiative.”

One might respond that the US-China rivalry could be driven by national security elites and their competing visions of the “national interest,” rather than by capitalist elites who would have otherwise preferred the globalized accumulation regime without the national divisions. In other words, due to the relative autonomy of the state from capitalist interests, interimperialist rivalries may have noneconomic causes. While this argument cannot be dismissed in principle (and, as we shall see, it plays a central role in explaining the US-Russian confrontation), it is hardly applicable to the US-China rivalry. Based on the historical record and Chinese strategic thinking, we might well deduce that China in particular is a reluctant imperialist nation, with a certain tradition of avoiding confrontation. Nevertheless, its relentless search for markets and investment opportunities abroad, driven by domestic overcapacity and capital overaccumulation, almost mechanically leads it to expand its global military presence as well, creating both the economic and the security tensions with the United States. Facing the threat of expanding Chinese capital (which is tightly interwoven with the state), factions of the US capitalist class have embraced a more confrontational stance toward China despite the economic interdependence between the two countries and the importance of the vast Chinese market for American businesses. The stage is set for the inter-imperialist rivalry that will define the twenty-first century.

In its core economic dynamic, the US-China rivalry harkens back to the classic Marxist theories of imperialism, such as those of Lenin and Luxemburg, defying the modern variations that have been developed to explain the period of the US-led globalization, such as the theory of the transnational capitalist class. This is not to say that the century-old Marxist theories of imperialism should simply be reapplied to the new context. Imperialism (the proactive use of economic, military, and other forms of coercion by one state against other states under conditions of strong asymmetry of power) and interimperialist rivalries (clashes between imperialist states over regional and global dominance) may have complex causes that cannot not be reduced to the contradictions of capital accumulation. Nevertheless, in some cases, as in the case of the modern US-China rivalry, the economic factors take center stage.

These factors reveal a potentially combustible situation. Michel Pettis provides an analysis that makes further confrontation seem practically inevitable. Today, China accounts for 18 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP). However, it comprises only 13 percent of global consumption while accounting for 32 percent of global investment and 31 percent of global manufacturing. If China manages to maintain the growth rates of 4 to 5 percent for the next decade while keeping its current investment-heavy model, its share of the global GDP would rise to 21 percent. Consumption, however, would still be less than 15 percent of the global total, while investment would climb to 38 percent and manufacturing to 36 percent. That would require the rest of the world to cede even more of its manufacturing capacity to China.

Leading capitalist powers are clearly no longer willing to accommodate China’s industrial growth as they enact protectionist measures and invest heavily in the domestic industry (e.g., the Biden administration has ushered in a new “manufacturing investment supercycle” in the United States). That leaves China with few options. One is to rebalance the economy toward domestic consumption, requiring an unprecedented shift in the country’s political economy that would encounter fierce resistance from the beneficiaries of the status quo (i.e., the existing investment-heavy export-oriented model). Another is to intensify the search for new markets, leading to increased global assertiveness. With its current growth model, China simply has no alternative besides “going out” and competing over the same markets with corporations headquartered in the Global North. According to Ho-fung Hung, “Intercapitalist competition between US and Chinese corporations is not confined to China’s domestic market — the competition has gone global.” While the intensifying US-China rivalry should not be reduced to the economic factors, its underlying economic mechanism is quite apparent and will remain at work for years to come.

Russia: Unleashing chaos

The Kremlin’s confrontation with the United States is of a different nature from that of the US-China rivalry. Post-Soviet Russia’s economic clout has always been far too limited to threaten the centers of capital accumulation in the Global North. Instead, Russian capital benefitted from global integration, particularly in the financial sphere, becoming one of the nodes in the global capitalist network anchored in the West. Russia’s claim to its “sphere of influence” in the post-Soviet space certainly has an underlying economic logic, as Russian corporations have sought regional expansion, both because of the need to reinvest surplus capital and the opportunity to reconstruct the Soviet-era supply chains under the control of Russian firms. However, the violent, annexationist turn of Russian imperialism since 2014 and its culmination in the 2022 invasion of Ukraine were not predicated on capitalist contradictions. In fact, they have dramatically undermined the international position of Russian capital. Some argue that the roots of Russian aggression against Ukraine lie in the “security dilemma”: eastward expansion of NATO, while providing security to the Eastern European states, also diminished Russia’s security, leading the Kremlin to finally “lash out” when Ukrainian NATO membership became a real, if distant, possibility in 2014.

This interpretation, however, overstates the actual security risks of NATO expansion to Russia (the owner of the world’s largest nuclear arsenal) and downplays the counterproductive nature of the Kremlin’s tendency to create conflicts supposedly to avoid them in the future. In fact, the Kremlin’s decisions in 2014 and 2022 were the product of a specific ideological vision that overemphasizes Russia’s vulnerabilities and calls for preventive military action under the slogan of “offense is the best defense.” The misperception of the actual threats and possible consequences of imperialist aggression was rooted in the deep fear and misunderstanding of grassroots popular movements such as the 2014 Maidan revolution in Ukraine and the 2011–12 opposition movement in Russia that the Kremlin could only conceive as foreign ploys. The fear for regime survival, sublimated as the fear of a Western conspiracy against Russia (or “Western encirclement” — even though there were no permanent NATO bases in the countries bordering Russia before 2014), created the toxic ideological narrative that ultimately made possible the annexation of Crimea, the intervention in Donbas, and finally, the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Russia’s conflict with the West, unlike the US-China rivalry, is rooted less in structural, particularly economic, causes and more in ideological (mis)perceptions. However, as contingent and ideologically motivated as Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine was, it had far-reaching global consequences.

One of such consequences is the newfound unity of the Western bloc, solidified by the response to the Russian aggression (although this unity remains precarious, as Donald Trump’s election in the United States and the subsequent foreign policy shift remain a possibility). The war in Ukraine has also had a profound influence on the US-China rivalry. In November 2023, trade between Russia and China surpassed the $200 billion mark. Russia is now China’s fifth-largest trading partner; not only a crucial supplier of energy and agricultural goods, but also a major recipient of industrial exports, particularly important in the context of enduring overcapacity. The economic relationship between Russia and China is highly asymmetrical, giving China an upper hand in the negotiations over the Power of Siberia 2 natural gas pipeline: the Chinese side understands that without the European market, Gazprom has practically nowhere to turn to in order to sell its gas. And yet, politically, the Kremlin is far from being China’s “vassal” as some analysts claim. For example, Putin managed to obtain Xi’s direct and public endorsement of his continued rule even at a time when he was the subject of an international war crimes investigation — thus making China invested in the survival of Putin’s government.

Both politically and economically, China and Russia are becoming increasingly interdependent. This does not yet make the two countries into an anti-Western “pole” in a nascent bipolar world, but it certainly puts additional strain on China’s relationship with the West. Putin was mindful of China’s increasing contradictions with the United States and other countries of the global North when he launched the invasion; he managed to intensify these contradictions. Not only structural economic factors, but also the Kremlin’s epoch-making war is pushing China away from the West. Chinese leaders are far from recklessly plunging into confrontation, as the Kremlin did in 2014, and yet the “push” factor is quite powerful.

Semiperiphery

In terms of their response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, semiperipheral countries can be divided into several groups. The first consists of highly isolated states locked into a full-on confrontation with the West, including North Korea, Iran, and Russia’s client state Syria. These countries provided Russia with military supplies, most notably, drones (Iran) and artillery shells (North Korea). This is unsurprising, given that they have nothing to lose from further aggravating the West and much to gain from a closer partnership with Russia. At $2.76 billion annually, Russia is now the biggest foreign investor in Iran. Russia’s addition to the community of pariah states gives more economic clout to this community, making it easier to survive Western sanctions together.

Among the major semiperipheral countries still remaining in the Western orbit and often identified as “sub-imperialist” in critical analyses, two types of response are notable. One is shamelessly exploiting the situation for material gain, such as Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Turkey or Narendra Modi’s India. While Turkey became one of Russia’s economic lifelines, with bilateral trade increasing by more than 50 percent since the invasion, India is now a key destination for Russian crude oil, which it refines and resells, often to the West. The responses of other subimperialist states, such as South Africa and Brazil, are less motivated by economic factors and include genuine, if largely misguided, attempts to resolve the conflict and achieve peace. Overall, a voting pattern of major semiperipheral states in the UN General Assembly (see Table 1) demonstrates a lack of desire to unequivocally condemn Russia’s war. However, even Turkey, diverging from this pattern, still expands its economic ties with Russia, including the supply of military-linked goods, revealing its international stance to be hypocritical and opportunistic. In fact, subimperialist states have generally used the war to claim their autonomy from the West, even as their populations largely condemn Russia’s aggression. Moreover, the two years since the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have seen the expansion of the international organizations alternative to the Western-dominated global order such as BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

Table 1: Semiperipheral countries’ votes on Ukraine-related resolutions in the UN General Assembly

| March 2, 2022: Condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine | March 24, 2022: Condemning Russia’s attacks on civilian populations | April 7, 2022: Suspending Russia’s membership in the UN Human Rights Council | October 12, 2022: Rejecting Russia’s annexation of Eastern and Southern Ukrainian regions | November 14, 2022: Demanding that Russia pays war reparations to Ukraine | February 23, 2023: A comprehensive, just and lasting peace in Ukraine | |

| Brazil | For | For | Abstain | For | Abstain | For |

| India | Abstain | Abstain | Abstain | Abstain | Abstain | Abstain |

| China | Abstain | Abstain | Against | Abstain | Against | Abstain |

| South Africa | Abstain | Abstain | Abstain | Abstain | Abstain | Abstain |

| Turkey | For | For | For | For | For | For |

| Iran | Abstain | Abstain | Against | Absent | Against | Abstain |

| North Korea | Against | Against | Against | Against | Against | Against |

The autonomy of subimperialist states still has clear limits, however. The biggest factor binding them to the US-centered international order is the dominance of the US dollar. Reflecting this currency’s unparalleled role, the New Development Bank, a BRICS institution, refused to fund projects in Russia in order to maintain its ability to raise money on global financial markets — even though Russia is one of the bank’s founders. While engaging in opportunistic attempts to skirt Western sanctions against Russia, countries such as Turkey are careful to avoid secondary sanctions made possible by the US dominance of the global financial system. A common BRICS currency, while increasingly discussed, remains a distant prospect, and the subimperialist states are in no hurry to join Russia with its limited ability to operate in US dollars. At the same time, the consequences of the increasing weaponization of the American currency and the gradual but unmistakable rise of Chinese yuan prompt the US establishment to take the threat to the dollar dominance seriously.

Regional conflicts

Regional conflicts such as the Gaza war have their own causes and logic that are irreducible to global transformations. Nevertheless, they are impacted by global developments. The Middle East is no longer dominated by the United States and its designs alone; instead, it is the site of interimperialist rivalry, with Russia and China meddling in the situation in their own ways, mostly with destructive consequences (the most striking example is Russia’s support of the murderous Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad). Emboldened by their support, Iran is pursuing an increasingly ambitious regional agenda through its proxies and allied formations in Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Yemen, and the Palestinian territories. Moreover, countries such as Syria have seen tensions and even direct military engagement between American and Russian forces. At the same time, Washington’s unrelenting support for Israel’s murderous campaign in Gaza despite the UN General Assembly’s multiple calls for a cease-fire further antagonizes the Global South and weakens the UN as an institution. Overall, the involvement of multiple imperialist powers in the region does not help to resolve its conflicts and alleviate tensions, instead creating more instability and violence.

A glaring example of this dysfunction is the UN Security Council’s track record on the Gaza war. Most of the cease-fire resolutions were, of course, vetoed by the United States, which bears the greatest responsibility for the deadlock. Several of them, however, were vetoed by Russia and China. Last October 18, the United States vetoed the Brazilian resolution, but Russia also abstained. When the Security Council was finally able to pass the cease-fire resolution this March 25, half a year into the war, the United States called it “non-binding” and proceeded to approve more military aid to Israel, which refused to comply with the resolution’s central demand. In effect, the Security Council proved completely irrelevant, with the United States doing most to ensure this, but with Russia and China having their hand in it as well. While the United States is primarily responsible for enabling the atrocities of the Gaza war (unyieldingly supplying Israel with weapons even as it makes feeble attempts to parachute humanitarian aid), the war is unfolding in a broader regional context in which Russia plays a powerful destabilizing role.

A separate question is whether we can call Israel itself “sub-imperialist.” It is engaged in aggression that is colonialist in nature (similar to Azerbaijan, for example) and it is certainly dependent on the United States, but it is not a regional power economically (like Russia or Brazil). For countries such as Israel and Azerbaijan, perhaps a special theoretical category should be adopted.

Imperialist world

Marxist international relations analysis, as it is currently practiced, is both equipped and unequipped to deal with the changes in the global order sketched above. On the one hand, it provides unique insight into the capitalist contradictions behind the interimperialist rivalries, helping to reveal the driving forces of world politics that other strands of international relations theory tend to downplay. On the other hand, when the economic causes of a country’s external aggression are not readily apparent, Marxist and left-wing commentators tend to either keep searching for such causes, making for rather strained arguments, or even deny the existence of imperialism altogether when it is glaringly obvious (as in the Russian case). At the same time, left-wing politics is by definition internationalist, and left-wing movements are uniquely sensitive (and vehemently opposed) to the various expressions of imperialism.

Consequently, there’s a gap: not just in our understanding of the world, but also between theory and practice when it comes to the politics of international solidarity. This calls for the renewed scholarly effort to understand the global dynamics of imperialism. It should be particularly attentive to the shifting position of the semiperipheral states. One theoretical concept often used to analyze their common trajectory is the concept of subimperialism. It emphasizes an intermediate position of economic dependency on the Global North and regional economic expansion, as well as “antagonistic cooperation” with the dominant imperialist power, the United States. However, this concept needs to be rethought and updated in view of Russia’s radical divergence from the subimperialist role and China’s rise to the position of an alternative center in the world system. These developments, as well as the changing nature of imperialism in the Global North (which increasingly resorts to protectionism, abandoning the global hegemonic aspirations of northern capital) affect the position of the semiperiphery. It should be studied through revealing both the external pressures and the domestic economic, political, and ideological processes involved in the foreign policy formation. In this way, authoritarian and imperialist definitions of “multipolarity” (such as the one advanced by Russia) can be distinguished from a truly internationalist foreign policy perspective.

Such a perspective should guide the global left-wing movements struggling both for peace between countries and radical change within countries — twin objectives that ought not be separated either in theory or in practice. In this struggle, the concept of imperialism is still indispensable — both as an analytical category that integrates the economic and noneconomic factors of interstate aggression and rivalries, and as a political category that guides the Left’s programs of action.

This essay was copublished by Alameda, an international institute for collective research rooted in contemporary social struggles. Ilya Matveev is a researcher in Russian and international political economy. He is currently a visiting scholar at UC Berkeley and a member of the research group Public Sociology Laboratory.