Australia: Labor consolidates as main party of capital, Greens’ left challenge has mixed results

“We are trying to fundamentally transform Australian politics, economy and society in favour of ordinary working people,” Greens housing spokesperson Max Chandler-Mather — who lost his seat of Griffith to Labor in the May 3 federal elections — told supporters on election night.

“And that sort of project will have more setbacks than victories, because the forces we are coming up against are enormously powerful… Time and again in history, brilliant people like you have suffered setback after setback after setback. And only after then have we cracked through and won.”

The incumbent Labor government of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese won an unexpectedly large victory in the elections. Labor was returned with a significantly increased majority of a likely 93 seats, up from 77.

The right-wing Liberals/National Coalition won just 43, 15 less than the 2022 election that itself marked the loss of 19 seats. Over two elections, the Coalition has lost close to half its seats.

As well as easily defeating the Coalition, Labor also took three of four lower house seats held by the left-of-centre Greens — including Greens leader Adam Bandt’s seat of Melbourne, which he had held since 2010.

New ‘main party of capitalism’

The biggest story of the elections was the disastrous performance of the Liberals, led by hard-right leader Peter Dutton. The Liberals crashed to its worst performance since its founding more than 80 years ago.

The Coalition’s primary vote collapsed to about 32% — 10% lower than 2019. The result occurred despite the cost-of-living and housing crises, and against a government who have raised passive inaction to an artform that should be studied.

The elections confirmed what previous ones suggested: the Liberals, historically Australia’s most electorally successful party and a major pillar of the two-party system, have collapsed as a mainstream centre-right party.

Furiously egged on by an increasingly irrelevant Murdoch press, the Liberals have descended into ideologically driven hard-right culture wars, alienating large parts of its traditional constituency (especially women, appalled by its misogyny). At the same time, it has failed to pick up alternative support in an increasingly multi-racial country it does not understand.

Labor has largely moved into the political space vacated by the Liberals, replacing the dysfunctional conservatives as the main party of Australian capitalism. Labor is now the predominant party of the establishment, backed by key sectors of capital (high profile, ideologically-driven exceptions such as billionaire Gina Rinehart notwithstanding).

But Labor has not taken all the space electorally. Since 2022, a swathe of traditionally Liberal seats have been won (and mostly defended) by a range of socially liberal independents.

Loosely known as the Teals, they are denounced by the Murdoch press as virtually Communist for believing women should exist in public life and that climate change is real. In fact, they are elected by people who voted Liberal until the party descended into farce.

Major party decline

The Liberals’ collapse is part of a larger trend that does not spare Labor. The 2022 elections featured a record low vote for the two major parties — until this election when it fell even further. One third of voters did not vote for Labor or the Liberal/Nationals Coalition.

Labor easily won the two-party preferred vote, but its primary vote only rose by 2.1% and remains at historically low levels. Labor outperformed expectations, but there is little evidence of popular confidence in its rule.

This marks a sense of alienation and distrust with the major parties that is underpinned by material realities. Living standards are falling. Whole generations are priced out of the housing market and rental stress is spiking housing insecurity and homelessness.

Healthcare and childcare costs are rising. Climate change-supercharged extreme weather is wreaking havoc and devastated communities (such as the northern NSW city of Lismore) are largely abandoned in the wake.

Many (especially Arabic and Muslim communities) feel fury and despair as Australia continues exporting lethal weapons to Israel, which is committing what Amnesty International, in a 300-page report, denounced unambiguously as genocide.

These issues affect different people differently across the country, but they add up to a political malaise. Few could honestly say they are being “represented” by either major party — whether they are well-heeled professionals in a blue-ribbon seat or struggling to pay the rent in deep suburbia.

Some are doing well, of course: property developers enjoying artificially inflated housing prices and generous tax breaks; and the 1 in 3 corporations who pay no tax at all. But below them there is uncertainty and fear for the future.

In this context, Dutton’s flirtation with MAGA-style politics backfired, with the uncertainty that US President Donald Trump has unleashed on the world making many uneasy. Yet the explanation for the Coalition’s result goes beyond Trump.

Dutton swung wildly from pushing (then abandoning) MAGA-like policies to decidedly unMAGA-like measures, such as matching Labor health spending promises cent-for-cent.

The Coalition also thought it wise to pledge to build nuclear power plants at unknown expense or timescale, leading to inevitable questions of exactly whose electorates these plants would be built in and which ones might get the waste.

The shocking quality of the Liberals’ campaign helps explain the result, but it is itself a symptom of the party’s degeneration.

Further evidence is what passes for “moderate” in today’s Liberal Party. Sussan Ley, an apparent “moderate” who has been elected the Liberals’ first-ever federal woman leader, spoke favourably earlier this year of the colonisation of Australia by comparing it to Elon Musk’s fantasy plan to colonise Mars.

Then again, Ley’s opponent in the race was Angus Taylor, who combines the stench of incompetence and corruption with membership of Dutton’s hard right faction. Anyone left in the Liberal Party caucus who accepts we live in the 21st century was hardly spoiled for choice.

Greens’ challenge

In this context, Labor’s shift to take the space abandoned by the Liberals has simultaneously opened space to its left. This explains its intense vitriol towards the Greens, the largest left-of-Labor party who quadrupled its lower house seats in 2022.

Labor fears not just the seepage of votes to their left but the potential for a more sustained challenge in its traditional heartlands. It fears the potential that a force such as the Greens could do to it what the Teals have done to the Liberals.

Post-election, Labor loudly gloated over the Greens’ lower house losses. A narrative has been pushed by Labor and the media that the result was a popular rejection of the Greens for daring to challenge Labor on several fronts.

Two issues have especially drawn Labor’s ire: the Greens’ demand for an end to support for Israeli crimes, and their refusal to pass Labor’s housing bill without amendments for months, on the apparently outrageous grounds it would make the housing crisis worse.

In reality, Labor refused for months to negotiate with the Greens over the housing bill. The Greens, led by Chandler-Mather, organised door-knocking campaigns in Labor electorates to talk to people directly about their position. All up, they knocked on 20,000 doors, with Chandler-Mather hosting a series of online “town halls” to discuss the campaign.

Showing contempt for ordinary people, Labor decried this campaign as the Greens acting in bad faith. The Greens eventually passed the bill, after negotiating $3.5 billion in direct funding for public housing.

Labor sought revenge, and poured resources into a successful bid to win Chandler-Mather’s seat back. Having offered gracious words to a defeated Dutton, Albanese laid the boot into Bandt and Chandler-Mather after their losses.

But it was not just Labor claiming victory against the Greens. Right-wing attack group Advance Australia, with millions of dollars in corporate donations, ran an hysterical campaign against the “extremist” Greens. After the elections, Advance implausibly claimed to have “destroyed” the Greens.

Greens’ vote

There are two key claims made by enemies of the Greens: that they were punished for their “intransigence” over housing and Gaza; and that they had supposedly strayed from their “roots”. The narrative does not add up on either front.

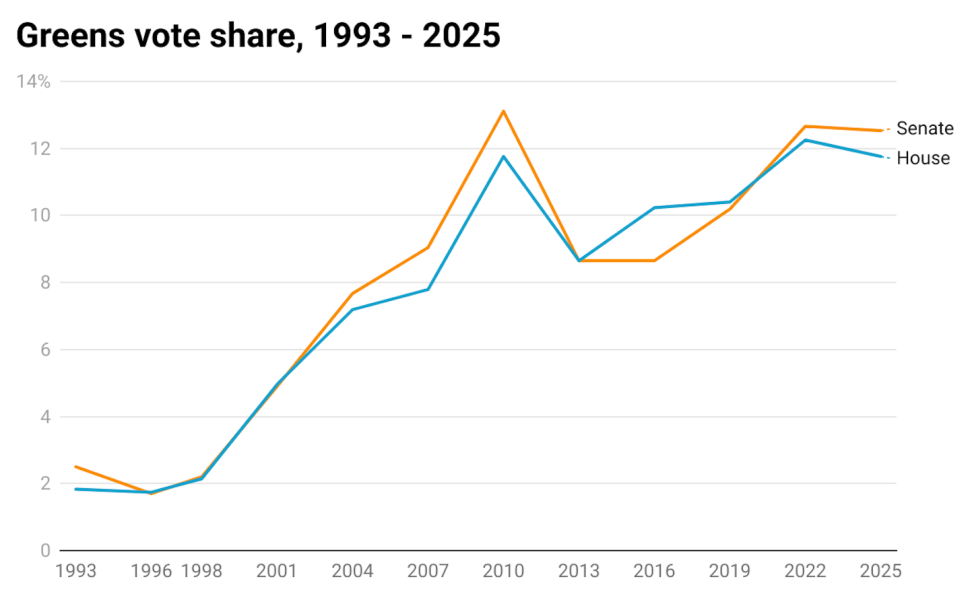

Nationally, the Greens’ lower house vote remained above 12%, down just -0.09% from its 2022 vote (as of May 18). Its Senate vote dropped to just below 12%, down 0.99%. However, by keeping all their Senate seats, the Greens have secured sole balance of power in the upper house.

The below graph shows the absurdity of claims the Greens have been “destroyed”.

The three lower house seats the Greens lost were less due to a supposed rejection of the Greens as to the mathematics of the preferential system.

With the collapse of the Liberal vote (much of which went to Labor), the two parties with the most votes in these seats were Labor and the Greens. Liberal preferences then flowed to Labor, giving them victory. Labor, having constantly accused the Greens of “collaborating” with the Coalition, owe these victories to Liberal preferences.

In Bandt’s case, a further factor was the redrawing of his seat’s boundaries. Public housing estates in which Bandt had built a strong base were moved to the neighbouring seat of Wills. In these areas, the Green vote was again high, with the Greens falling just short of winning Wills for the first time.

There is some nuance to the Greens national vote, however. There were swings against the Greens in some inner-city seats, and swings to the Greens in various multi-racial working-class areas. This occurred in southern Brisbane, western Melbourne and most impressively in Western Sydney, with the Greens securing swings in every seat across the region.

In the Western Sydney seat of Blaxland, the lower house swing to the Greens was only about 1%, with a strong Muslim Votes Matter (MVM)-backed independent campaign channeling much of the local fury at Labor over inaction around Gaza and other issues. But the Senate vote in the seat more than doubled, from just under 6% to more than 13%.

Western Sydney also shows the independents’ challenge affects Labor too. In Fowler, incumbent independent Dai Le — who dramatically won the seat from Labor in 2022 — was re-elected. As with Blaxland, the neighbouring seat of Watson also saw a MVM-backed independent ride waves of community anger to significantly reduce Labor’s previously large winning margins. MVM candidates have insisted they are only getting started.

Greens’ ‘roots’

The second claim about the Greens is they have abandoned their supposed roots as a purely “environmental party” by taking up such causes such as housing and Gaza.

Presumably this also includes their push to expand Medicare to include dental (a huge expense for many people), to abolish student debt and make education free, and to provide free child care — all to be paid for by new corporate taxes.

It does not take much imagination to look at these policies and see the ghost of the Gough Whitlam Labor government. Elected in 1972, in just three years the Whitlam government famously extracted Australia from the Vietnam War, created Medicare and introduced free education, among other reforms of the sort Labor has not just stopped promising but, in government, actively worked to undermine.

The Greens seeking to take up this reforming legacy embarrasses a Labor that wants the Greens to sit in the corner and talk about trees. Of course, critics of the Greens chose not to notice the Greens also condemning Labor for opening new coal and gas mines, calling instead for a major expansion of renewables.

It also ignores the actual Greens’ history. The Greens were formed in the 1980s and early ‘90s around four pillars:

Ecological sustainability;

Social justice and economic equality;

Participatory democracy; and

Peace and non-violence.

The Greens have always stood for more than just “the environment”. Exactly how they have approached broad social issues, and the exact mix in their focus, has varied over the years. But variations of the mix they campaigned for in 2025 were there from the start.

If anything, the Greens do not always fully synthesise these four pillars; that is, treat them as parts of a connected whole. The Greens sometimes present different policies as if they are siloed proposals with little connection to each other: over here is climate action, in an unrelated column is housing, in the next unrelated column is First Nations justice, and in a different silo altogether is ending the US military alliance and supporting Gaza.

Yet they are all connected — Greens policies on these issues represent a challenge to the current powers-that-be and their system. Both major parties act as they do because they are beholden to the actual economic centres of power in society.

The same corporate interests making huge profits from fossil fuels are intricately connected to the property industry (just look at where major banks’ capital is invested). This economic power sees its interests as best served globally by allying with the US, part of which means uncritical support for Israel.

It is entirely consistent for the Greens to talk at the same time about ecological sustainability, and housing, and refugee rights, and peace, and economic inequality and plenty of other injustices — both in terms of their own founding principles and the reality of the country.

Breakthroughs

Exactly how to best express this is a big question.The electoral breakthrough for the Greens in Brisbane in 2022, where they shocked the political establishment by winning three inner-suburban seats, was closely associated with a push to emphasising “universalist” type politics. This emphasises collective interests of the majority against a political class that serves a powerful minority.

Led by a tendency emerging from their South Brisbane branch, the Queensland Greens have grown in electoral strength from about 2015 through a focus on grassroots work to build community support that can challenge a political establishment captured by corporate interests.

These politics were seen most clearly in Chandler-Mather’s high profile campaigning on housing. But they were also symbolised by Greens’ Brisbane MP Stephen Bates, a young working-class queer man, who was just 29 and famously working a retail job when he won his seat in 2022.

Outside the media glare, the Greens used these new seats to set up local free meals programs and other forms of financial help for those struggling, largely funded out of their MP’s salaries. They also campaigned on a range of local issues such as flight noise and plans to close a public school to redevelop a stadium.

Chandler-Mather was explicit about his project. When myself and LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal editor Federico Fuentes did a 2-hour interview with him in late 2023, Chandler-Mather insisted the goal was to transform the Greens into a mass working-class party.

His interventions in parliament showed how his project was aimed against the “political class” as a whole. In one viral clip of a parliamentary speech, as he tried telling the story of a desperate constituent in the face of Labor jeers, an emotional Chandler-Mather spoke over the heads of MPs to “anyone watching”, insisting that the thing that scared the political class most was ordinary people having hope.

When Labor brought in profoundly undemocratic laws to gut the Construction, Forestry and Maritime Employees Union (CFMEU), using long-standing criminality in the construction industry as its excuse, Chandler-Mather addressed an angry rally of union members, copping further abuse from Labor and the media for daring to do so.

No wonder Labor worked so hard to unseat him, and Albanese sneered so unpleasantly when they did.

In this context, a rise in Green votes in more working-class areas may be important. It is far too soon, and the shift still too limited, to draw hard conclusions, but it is certainly possible the more universalist-type messaging and policies found a stronger resonance in these areas (as did support for Gaza in places like Western Sydney).

In Western Sydney, the swings built on a growing vote in the region in the 2024 local council elections. Amid a higher vote across the area, the Greens won seats on Blacktown and Cumberland councils for the first time.

Campaign message

Yet despite those Green shoots, it is hard not to feel the Greens’ election campaign missed opportunities. Amid a crisis of legitimacy for the major parties, with space opening up on the left and people’s living conditions worsening, the Greens vote stayed steady rather than grew.

In particular, the perspective pushed by Chandler-Mather in the 2023 interview has undoubtedly taken a hit. It is not just that the three seats lost were held by figures who seemed clearly associated (to varying degrees) with this social democratic reform-type perspective, this perspective already seemed weaker in the Greens election campaign itself.

Two factors seemed to be behind this. The first was the 2024 Queensland state elections, in which the Green vote in inner-suburban Brisbane stalled for the first time since 2015. The second was the election of Trump just a few weeks later.

The Greens took a well-developed platform to the Queensland election with a heavy focus on public ownership to tackle the myriad of crises people faced. But with the Liberal National Party (LNP) poised to win, the election instead centred on the contest between the LNP and incumbent Labor government, which ran some watered down versions of popular Greens policies to save what they could.

In the aftermath, there was a sense the Greens, in campaigning hard against the status quo in general, had not done enough to make clear their specific opposition to the LNP and its profoundly reactionary platform. When Trump won the US elections, this concern seemed to deepen.

It led to a seeming over-correction, with the Greens federal campaign slogans overwhelmingly emphasised stopping Dutton, and explicitly connecting him to Trump. To this, they added that the Greens would “push Labor to act”.

With the exception of the heavily publicised “put dental into Medicare” proposal, this largely crowded out actual policies. Other measures with potentially wide appeal, such as combining rent caps with creating a public developer to build badly needed homes, received less focus.

The Greens powerful message to sanction Israel and cease arms deals in the midst of Israel’s genocide was also quieter than the constant refrain of “Keep Dutton out, make Labor act”.

At its most extreme, the Greens even talked of a potential “golden era of progressive reform” if a minority Labor government had to negotiate with Greens MPs able to “pressure” Labor to do the right thing.

Weaknesses

The problem is, it is hard to condemn Labor so strongly for active complicity in the Gaza genocide, then suggest they might bring in a golden era of reform if only enough Greens MPs are there to “push” them.

No doubt this messaging did reflect real pressures on the Greens. Much of their traditional middle-class base, especially in inner cities where they were trying to hold or win new seats, were understandably horrified at the thought of a Dutton prime ministership.

But campaigning in the Western Sydney seat of Blaxland (admittedly a Labor safe seat where the main challenge came from a Muslim independent), Dutton was not a big factor among people coping with collapsing living standards and often seething with rage over Gaza.

People, but in particular those from the local Muslim community, ignored Dutton and directed their fire squarely at the party in government, giving expression to their community’s widespread sense of being ignored and betrayed.

In this regard, part of the issue may be a need for greater flexibility in campaigning, with more space for different emphasises around the same basic policy focuses. Reassuring a voter in Griffith or Melbourne that the Greens strongly oppose Dutton is understandable, but in Western Sydney the concerns are very different.

Part of the problem of so heavily emphasising “keep Dutton out” is that it did little to give people a reason to vote for the Greens specifically. After all, Dutton is to the right of most of Australian society, including large chunks of the Liberals’ traditional base. To oppose Dutton, you do not need to vote Green; there were no shortage of other candidates wanting to stop him too.

The attempted point of differentiation was the call to push Labor “to act”, but this can ring false. It is not just that the Greens had spent the past three years denouncing Labor (accurately) as a political arm of the property and fossil fuel industries, and (accurately) as being complicit in genocide.

The harsh reality is few people have any hope or expectation Labor will do anything good at all. Even people voting Labor do not really expect that — they just looked at the alternative.

There is a layer of politically engaged progressive people who believe that with the right mathematical outcome of seats some positive reforms may be possible — a minority Labor government plus Greens’ and independents’ support equals change. But this does not really translate to broader society: people hear “keep out Dutton and make Labor act” as “support Labor”.

There is no guarantee, of course, that a different approach would have led to a better electoral outcome. But this is not simply about votes in one election; rather it is about what type of politics you wish to campaign on.

After the breakthroughs of 2022 on universalist-type politics that targeted the political class as a whole, it feels like the Greens missed the chance to more fully test out the type of politics that led to that historic breakthrough.

One thing that should also be emphasised is that the Greens operate under a resource stretch that the major parties do not. Swings in places such as Western Sydney were achieved with very limited resources, and pose the question of what potential support might be won with more.

In Brisbane, the party had to direct a lot of resources and energy to try and keep their three inner-suburban seats (ultimately only keeping Ryan), posing the question of what further gains could have been made in southern Brisbane with bigger campaigns.

This connects to a further challenge from frequently hostile media coverage, which amplified Labor’s lines of attack. How much damage this does can be hard to gauge, but successfully countering it requires strong on-the-ground campaigns.

Future directions

With Bandt losing his seat, the Greens have now elected Queensland Senator Larrisa Waters as parliamentary leader, with NSW Senator and high-profile voice for Palestine Mehreen Faruqi remaining as deputy leader.

All the public messaging has so far emphasised a refusal to back down in the face of Labor and media pressure on issues such as Gaza and housing. Former leader and party grandee Bob Brown even took to the media to urge the Greens to go harder against “Labor arrogance”.

If anything, Labor attacks may well be helping the Greens post-election. It gives the Greens the chance to say clearly: “we aren’t going to stop opposing war crimes or supporting people’s right to affordable housing”. Labor is providing the sharp differentiation between themselves and the Greens that was lacking in much of the campaign itself.

The question remains though, whether the Greens will focus on their more traditional role of seeking to be a “moral voice” that “holds power to account” from within the political system, or seek to challenge the political status quo itself.

Waters’ message of wanting politics “with a heart” could suggest a more “moral voice” emphasis. There can be a pull towards this approach due to the Greens’ weight in the Senate, where the party has the balance of power.

It favours an approach of high-profile commentary through the media, whereas trying to win and hold lower house seats requires more localised community base-building.

On the other hand, the swings in multi-racial, working-class areas, achieved with still-limited campaigning, suggest the potential for the Greens to extend beyond their largely middle-class constituency and take more of the political space Labor has abandoned. The Greens may have lost three of their four lower house seats, but they are within touching distance of winning at least a handful in the next election.

The most likely outcome will be a mix of both approaches, with the exact weight of either and how they interact to be determined. The party appears optimistic about increasing their presence and vote in places such as Western Sydney. The next period will provide no shortage of opportunities for a political force willing to organise around people’s collective interests.

In this regard — and in terms of the space to the left of Labor — it is also worth noting the sizable swings to socialist candidates in several Victorian seats. In Wills, socialist councillor Sue Bolton, who has built a base through constant involvement in community campaigns, received a swing of more than 5% to win 8% of the vote (unprecedented for her party Socialist Alliance).

The Victorian Socialists, who ran high-profile social media figure and renters’ rights advocate Jordan van den Lamb (known as “purple pingers”) for the Senate, also received significant swings and high votes by socialist campaign standards in several Melbourne seats.

In a sign of often-elusive socialist unity, SA and VS ran a joint campaign in Wills, producing material supporting Bolton for the lower house and VS for the Senate.

The story of these results and associated campaigns is best told by those directly involved, but these experiences will be part of the process of building a serious challenge rooted in working-class politics to the political establishment.

The post-election announcement by VS that they plan to extend the party across the country and run candidates in every state shows they are seeking to build on their solid results over several elections in Victoria.

Overall, the elections marked a win for the status quo: an incumbent government, which has done little of note, secured a larger majority without winning many more votes, against an Opposition that has largely collapsed into dysfunction.

For the Greens, having secured a big breakthrough last time, it shows progress is not linear: while their vote held up, forward momentum was stalled. The space for a serious challenge built around collective interests from below remains — with the added urgency that global politics shows the potential for right-wing populist forces to harness dissatisfaction with the status quo.

Stuart Munckton is a member of the Parramatta Greens. A longer version of this piece was published on his blog.