‘There are no recipes for socialism’: interview with Hugo Moldiz, Bolivian Marxist

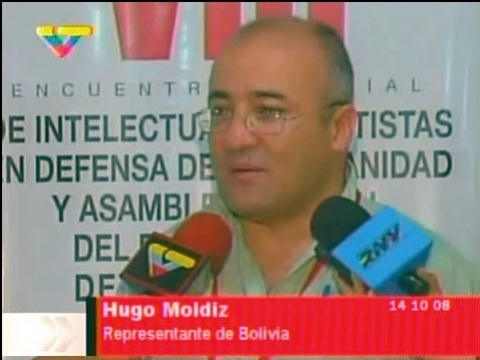

Hugo Moldiz interviewed by Coral Wynter and Jim McIlroy

April 24, 2013 – Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal – Hugo Moldiz is a respected Marxist journalist and author living in La Paz. He has written several books, including Bolivia in the Times of Evo, published by Ocean Sur in 2009. He is editor of the weekly La Epoca and has also contributed many articles to the magazine America XXI. We interviewed him during a recent visit to La Paz, Bolivia. Translation from the Spanish by Coral Wynter.

* * *

What is the significance of the election of an Indigenous president in Bolivia?

The very fact of the election of an Indian to the highest level of government, to the presidency, was a revolutionary act. This may not mean so much in other parts of the world, but when we understand the nature of the social formation in Bolivia, it is very significant. This is due to the way the republic was established [in 1825] and its development based on the past colonial period, involving the development of forms of capitalist control over work and the stealing of our natural resources (the source of the original capital).

Successive governments further entrenched this by the almost total exclusion of the majority of people, the Indigenous people, from political participation. It was a double exclusion for the Indigenous people – from political power as well as from participation in society. If you want to look at it in class terms and also from the point of view of the national culture, capitalism in countries like Bolivia has been sustained by colonialism. Thus from this perspective, the arrival of Evo Morales was very significant and resulted from the emergence of an Indigenous, peasant and popular movement and the formation of a new power bloc that is moving to displace the old power structure.

What is the proportion of Indigenous people among the overall population of Bolivia?

In the last census in 2001, 64% of the Bolivian population was recognised as Indigenous. The proportion could be even higher because, before the victory of Evo Morales, before the inclusion process, the Indigenous and peasant movement was only just emerging. From about 2000, or even a little before, there was a process of construction of collectives, of an increase of Indigenous self-esteem. In the previous census of 1991, there was a minimal percentage of Indians who considered themselves Indigenous. This happened not only because the census didn’t ask the question whether people identified as Indigenous. On top of this, people of Indigenous origin viewed the census as an instrument of oppression in society.

For Indians who lived in the city, they considered themselves anything but Indian, because the word “Indio” was a bad word. If I were Indian, I had to present an identity card as an Indian, which would not open doors for me, but rather close them.

I think in this census [which was held on November 21, 2012], the number of people who identify as Indian will be more than 64%. When we speak of “Indio”, we are not just speaking of peasants: we are talking about the Indigenous people. Peasant is a concept of class: we are talking about Indigenous people who live in both rural and urban areas.

In addition, we are going to see the planning of the economy in the period up to 2025. A second major aim is to have a better distribution of national wealth. Until now, the distribution of wealth in Bolivia has been regulated by the number of people who live in a certain area. Today the proposal is to change that criterion, or at least complement it, to establish a better basis for access to basic services, which is one of the 2025 objectives of the president.

What changes has the pursuit of policies against neoliberalism brought in the Bolivian economy?

It is very difficult to sustain the thesis that the government of Evo Morales is a neoliberal government. But some, from the more extreme left, maintain this idea. One of the important features of neoliberalism has been, rather than the absence of the state, the clear role of the state in neoliberal policy. In the first place, the state delivers our natural resources to the transnationals, into private hands and the hands of the foreign capitalists. In reality, neoliberalism reduces the national economy in a country like Bolivia. With Evo Morales we have a model that is not neoliberal, but a different economic model that still has some features of neoliberalism. We need to see the state return to an instrument with huge involvement in the economy. We have so far achieved about 40%, but we always need to analyse the point of departure. And in this country, the state had previously been reduced to no more than 10% participation in the economy. So we have significantly recuperated the role of the state.

Also, there is a process under way of re-appropriating our natural resources. This is quite different to neoliberalism. There is the reconstruction of the internal market, which was destroyed by the neoliberal model over many years. There was a process of depreciation of our national currency, the bolivar. A country like Ecuador, which previously converted to US dollars and also now has a left-wing government, faces many difficulties returning to a national currency. Here, the value of the national currency has been increased, which gives a measure of protection to the workers. Another characteristic of neoliberalism is flexibility of payment to the workers. In Bolivia, it has not yet improved as much as we want, but still the state took legal measures to protect the rights of labour.

The social security system is currently being expanded. During the period of neoliberalism, as in other countries, instead of funding going to social security, it was privatised and handed over to AFPs [private pension funds]. The AFPs cheated on payments, or did what they wanted with the money without any controls. There was no guarantee that the workers would receive their proper social security or could carry it over. And there were many people who had never been able to access social security or had very little.

The Morales government has reformed social security and those who earn the most support a common fund based on a percentage of income, which guarantees a retirement income to a person, according the number of years they have worked. It still doesn’t cover informal workers. That will be the second step, for workers who haven’t achieved enough points to have a dignified retirement. Retirement age is currently 65, but soon this will be reduced to 55 years.

For single mothers and widows, there are various bonuses. All the elderly receive a dignified income, including those who have a retirement fund. There are also extras for parents with children, for those of school age and for pregnant women. I know in some countries of Europe, this is not a novelty. But the USA and Europe have robbed so much wealth from Latin America, our people live like semi-slaves. We know that the social gains are limited so far. They would be very small payments compared to Europe. But these measures have been very important in Bolivia.

Bolivia has taken a leading role in the international environment movement, giving legal rights to Pachamama, Mother Earth. What is your opinion on this issue?

I think that the support for the Bolivian revolution, the Indigenous movement, MAS [Movement for Socialism] and Evo Morales and the fight by our people is not just for a better society in Bolivia. No, it’s for a better world and that means support from all of society for the revolution and the re-evaluation of nature. But not with the logic of capitalism, because capital also gives value to nature, but it gives the same value to nature as it gives to the forces of labour, an exchange value that will generate a profit. We need another value in the form of life.

At the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, we were obliged to guarantee the generation of employment. But this also obliges us to try to overcome the limitations of nature. Therefore, this necessitates a change in our fight for emancipation. Emancipation has a humanist basis. Clearly, neither Marx nor the 19th century philosophers can be blamed for not fully foreseeing the problems of the environment and nature. Today in the fight for a better world, we cannot disconnect or separate human beings from nature. You have to liberate both, emancipate both. In particular, this is very important for Indigenous people. For Indigenous society, this idea stumbles against the reality of the world. This reality, from the time of the invasion of the Europeans, has determined the conditions of our countries that provide the raw materials to the West. For countries like Mexico, Bolivia and many more, our economy has been based on plantations and the exploitation of our natural resources. This role in the world economy has to change.

This change, which many comrades don’t understand and are therefore critical of, cannot be implemented by Bolivia alone. This is a worldwide struggle, or at least continental, at this stage. And neither can it be done overnight. But we can see it on the horizon, because of the level of the fight.

The communist horizon was opened up by Karl Marx. Marx didn’t see it in his time and couldn’t predict a time of communism, but he opened up the communist horizon. The vision of another possible world, the vision of all of us wishing to live well, has opened up. We don’t know when or how we are going to construct this world of living well. It would be the complementarity between humanity and nature. But in all ways, it implies change.

There is no science, no social science, that does not consider the theme of nature, inside its own knowledge base. For myself, I cannot see a political economy that does not take into account the theme of nature. This is also one of the themes of Marx. When Marx in the Grundisse says, the “land is the extension of the human body, of the community”, what is described is the deepening relationship between human beings and the land. What has happened in Bolivia is a discussion, with some foolish academics thinking they have just discovered this problem today. Evo puts a lot of importance on Pachamama.

Pachamama is not a mad, esoteric ideology. Why do we love Pachamama? Pachamama involves a religiosity which is very materialistic. It is not Christianity, nor Catholicism, nor it is idealistic. It’s materialistic, because Pachamama is the land. It is what you eat, it is the extension of your body. This is what gives it importance. You have to give “rights” to Mother Nature. The Ecuadoran constitution does not contain formal recognition of these rights as in the Bolivian constitution, but it is evident in the political thinking in that country.

There appear to be a lot of challenges at present in Bolivia, with issues such as divisions in the mineworkers’ organisations, among Indigenous communities over the road through the forest and the recent blockade of the highways. How is the Morales government handling these issues?

The nature of the conflicts with the Evo Morales government are different to the nature of the conflicts with previous governments. The common denominator is that they are conflicts, but we must uncover a little more information about the nature of these disputes. In the time of the governments prior to Evo, the main fight was against the bourgeoisie by all of the communities for a share of the economy. In general, since the bourgeoisie had the resources of the government, along with the state, this fight over the surplus was won by the bourgeoisie and the dominant classes in this country.

Now the fight for the surplus wealth is almost horizontal. It is not those below fighting those above. It is not vertical. Today, the fight is for an equal share of the cake. We all want to eat a larger slice of the cake. This in itself is not bad because it implies a process of empowerment of the people in the country. This empowerment was not possible without the new constitution.

The constitution gave the communities many rights. For the first time, our new constitution, via a constituent assembly in January 2009, recognised the rights of the collective. Our constitution previously only recognised the rights of the individual, liberty of expression, civil rights and political rights. Our new constitution now does not deny these rights of the individual, but also recognises the rights of the collective. This gives a lot of power to the people and the people are using this power. Because today the contradictions are between state sovereignty and collective rights. The people want so many rights, which even includes wanting to devour their own state, overcoming the national authority. In reality, this creates an interesting situation. It is neither good nor bad in itself. It will oblige us to look for new mechanisms or scenarios of expression. If we analyse this purely in terms of how the state conducts itself in the traditional way, it appears people are confronting the government and the government doesn’t control anything.

But it is not really like that. It is more complicated. It appears we have a process in which the people are confronting Evo Morales. But the truth is not that at all. Because transport strikes we have experienced, the mining strike against the co-operatives are temporary. When the elections come around, these two sectors will end up voting for and supporting Evo Morales. For this reason, you have to take care against being frightened by the conflicts. At times, the bourgeoisie and the communications media at the service of the bourgeoisie try to amplify and distort the nature of these conflicts and talk about a different reality.

We are not going to find in Marx or Lenin, nor in the reading of small stones, nor in the wrinkles of grandparents, the recipe to go forward. We will only find this recipe in the course of the journey. There are no recipes for socialism. There are the great thinkers, great trains of thought, but no recipe. Not by Marx nor Lenin nor Che (I am a Guevarist. I am a member of the National Liberation Army or ELN, that Che founded).

Che called the programs of these founders of political economy manuals for how to make bricks. There were many errors in the Soviet Union. The Soviet leaders after Lenin removed the elements of creative Marxism. There are great ideas for sure, but at times contradictory, because, on the one side, we are creating a new state and, on the other, the old state continues. Therefore as everything is related socially, if it is constructed badly, this state is going to end up re-consolidating the old state. It is going to undermine the new state.

Our revolution is fundamentally non-violent. This is an advantage, but also it is a problem. If the revolution imposed violence, it would be easier to overcome certain things in terms of construction of the new state. What we must do is change structures and work in parallel. Dismantle the old and create the new. There are problems, clashes, stoppages, bad treatment. The process has many contradictions.

Why were the highways blocked by two different communities [in the lead-up to the national census in mid November, 2012]?

The money shared between the municipal councils in Bolivia is calculated in part by the number of people in a municipality. Therefore, if municipality A, say Villa Tunari, is put into municipality B, say Colomi, it becomes a problem of boundaries. We are going to change that, but the government hasn’t confirmed this yet. The solution is not to distribute the money simply on the basis of the number of people who live in a municipality. That method is not correct. It’s better to distribute the money on the basis of fair access to basic necessities. We believe that in 2025, the whole country will have access to basic services: light, water, telephone, internet (because it is now one of the basic services), housing and sewerage. This is socialism: that everybody has access to all these things. On the other hand, it is not fair to give resources to one city where there are already some services and not to invest in other places where there are no resources. The criterion should be to prioritise those municipalities that don’t yet have basic services.

What basic improvements have taken place in the economy, with regard to the standard of living and the rights of the people, under the Morales government?

This is a government that has increased workers’ salaries much more than any other. During the 20 years when neoliberal governments increased salaries, the maximum was 3%, but only for public servants and not for private business. They used to leave open the negotiations between the private sector and workers. Evo made it obligatory to raise the minimum wage for workers in private business as well as the state sector. Second, the average annual increase under the Morales government has been around 8-10%. Third, other sources of work have emerged.

The state has recovered control of the economy, so that the number of workers in recovered companies has also increased. These include the nationalisations of the oil industry, the tin mine at Huanuni, the tin smelter at Vinto owned by Glencore [a Swiss-based company], the telecommunications company, Entel and the major generators of electricity. This means more resources for the state and also increases the sources of work. Nevertheless, neoliberalism was so bad in this country, that so far we still haven’t resolved a lot of problems.

The government doesn’t have a magic wand, by which it can employ everybody instantly. There are hard realities that we must touch on: the reality of the world is that of change in the domain of work, and this has changed a lot. We need to discuss what this implies for the process of revolutionary transformation.

It is very difficult for a revolutionary government to be capable of guaranteeing work for everybody in the state or the private sector. We have to think about this. What is the importance of the economy within the community? How can we produce collectively? How can we also appropriate the results of our work for ourselves? How do we generate new mechanisms of exchange? In some areas we can do this without the mediation of money. It’s possible.

In the province of Comanche in La Paz, there are communities that mediate exchange without money. It’s a relationship of trueque [barter]. They are an Aymara Indigenous community. Perhaps there is another way of doing things. How can we de-commercialise this relationship that we have in the capitalist economy? This is an important topic for the workers and the peasants.

The big problem is the workers sometimes do not protest so much against neoliberalism, but against Evo Morales, which at times is not justified. But at the same time, I think it’s good because they are pressuring the state, because all states tend to be conservative. So it is positive pressure against the state.

What is the strength of the right-wing and separatist movement, under the name Media Luna, opposing the Morales government and what are their tactics at present?

The Media Luna doesn’t exist now. The Media Luna was a political plan of the ultraright wing in the provinces of Santa Cruz, Beni, Pan de Tarija and Sucre, that is four departments and a city. They intended to divide the country between western Bolivia and the east. They wanted a coup d’état in Bolivia. They wanted to remove Evo Morales from the government. This was not clear in the first moments of their action, but they planned to take over the presidential palace. This action proved to be impossible in practice.

The idea was to divide the country and occupy half of the territory, including with armed groups. This would have been only temporary and later, a second move was to be the intervention of the United Nations, the Blue Helmets of the UN. We all know the UN is an extension of the Security Council, run by the USA. This was the model of the coup they were thinking of during the first term of the Morales government in 2006.

It was defeated in 2008. Now this right wing doesn’t exist. The government now has a lot of influence in Tarija, Santa Cruz and Pando, where the governor is aligned with Morales. We have elections next in Beni, where the government will probably win.[1] The concept of Media Luna does not exist. This came about in the first period of government, but is now defeated.

Now, the second question is about the state of the right wing generally. In terms of a political party it does not exist, either. It is defeated and fragmented. Those who are playing the role of the right-wing parties and an opposition are the mass media and the communications industry. The right wing don’t have a viable candidate and do not have a viable project. And, as in Venezuela, the opposition’s own leaders don’t dare speak against the changes. They are “in agreement” with the changes. Capriles did the same in Venezuela. But in Bolivia they are very fragmented. I think it is not a big problem for the Morales government.

The army is maintaining its loyalty to the government. The police in one sector tried to generate a coup d’état scenario, similar to what occurred in Ecuador. But then the military inserted themselves. And finally, there was a new victory for the government, but also for the social movements, who demonstrated in their thousands in the city of La Paz. Many of us spent those days in the streets without sleeping. Huge crowds of people came and went, masses of peasants coming from El Alto, in their thousands and thousands and they spread throughout the city of La Paz, until the city was absolutely full.

Talking of Media Luna, if today there is a city where racism has surged along with the spirit of conservatism, it is the city of La Paz, not Santa Cruz. La Paz is the centre of racism and rejection of the Morales government. The US has never stopped intervening. The USA organised and financed the Bolivian opposition openly, absolutely disgracefully, during the first Morales government. During Morales’ second term, until today, it keeps doing it but much more secretly.

There are statements from President Obama against Bolivia and Brazil, which are very aggressive. We have been decertified in the fight against narcotrafficking, when among the Andean countries, we are the country that has most reduced the area given to coca-leaf production. The Andean Community has certified that our country is where the most number of operations against drugs have been carried out. [Former] US Secretary of State Hilary Clinton was always referring to the bad aspects of our relationship with Iran, our bad deeds in relation to Cuba, etc.

So the USA maintains a foreign policy that is pretty aggressive against Bolivia, as well as Venezuela. In the march by the Indigenous for Dignity, opposing the construction of the highway in Beni, some Indigenous people mobilised against Evo, but they were financed by the NGOs and the resources of the US government. There is a very active presence of the USA in Bolivia.

The development of the Bolivarian Alternative for Latin America (ALBA) is crucial to the growing unity of progressive countries in Latin America. How do you see this process developing?

Latin America is a laboratory where we are doing many new things. The small corner of the world about which Karl Marx spoke in Europe in the 19th century is Latin America today. We don’t know how we are going to come out of these experiments. But until now, we can say after almost 200 years, we are in a good period, although surrounded by dangers.

But I think Latin America is not the same today as in the past. The triumph of the Cuban Revolution marked the beginning of a new stage. This was the third emancipation in Latin America. The third emancipation is my reclassification of the history of Latin America. The other two were the Indigenous resistance and the 19th century independence struggles against Spain. So this third upsurge came about with revolutionary Cuba.

When it appeared the world went into obscurity with the fall of the Soviet Union, it wasn’t long, after only a few years, before Latin America emerged offering a ray of hope. This became a beacon of hope because of the generalised fight against imperialism by the social movements of the Latin American revolution.

I cannot analyse politically the Zapatistas in the decade of the 1990s, but we found three things to confirm the rising up of Latin America.

1. The rise of the Zapatistas in Mexico in 1994.

2. The emergence of the peasants and Indigenous peoples of Bolivia and Ecuador, constructing their own political instruments.

3. The victory of Hugo Chavez in Venezuela in 1998.

These three events denoted a favourable political situation. Although the Zapatistas did not triumph in terms of taking state power, their fight and their ideas are an example of another social movement. One cannot say it meant nothing. In historical context, I am not a Zapatista. But to understand what is happening in Latin America, you have to look at the Zapatistas’ revolt objectively, including its impact on what is occurring now in Bolivia.

For this reason, we need to overcome the model dictating that there is only one choice of paths, either through capitalism or through socialism in simple terms. We need to look at various models revealing other means of transformation. There is a debate here in Latin America about various projects of emancipation, not only one. It’s not important if it is called “Socialism of the 21st century”, as in Venezuela, or another name. In Ecuador it is Vivir Bien [Live Well]; in Bolivia it’s communitarian socialism, but they are different projects for emancipation. They are not equal. But they have commonalities, similar ties connecting the models. They have various means of articulation.

I think that the Zapatismo had more impact outside Mexico than inside. This is important because of its influence in a globalised, unipolar world.

The fall of the Soviet Union destroyed our dreams. But the positive side of this negative event was that it forced Latin Americans to think with our own brains. The left in Latin America thought from the viewpoint of Europe. They thought only of the working class of Karl Marx, but it was a Eurocentric vision. Since if you were not part of the working class, you didn’t play a role. It was a distorted interpretation of Marx.

The Trotskyist left and the Stalinist forces in Latin America did a lot of damage to the struggle of our people because they translated mechanically and automatically what Marx thought about Europe to Latin America. And they took out its creative essence. I was always against treating Marxism solely as a science. But included in this, many on the left also took out its scientific content. They converted it into a bible.

The “Marxists” are partly to blame for why today so many Indigenous people, including in this country, do not believe in socialism. How are we going to believe in Marxism and socialism if it doesn’t take into account the Indigenous people? “Official” Marxism did not involve the peasants or the Indigenous. I have been a Marxist for many years, but you must give Marxism its true character. You can’t say it’s just a social science, because that destroys its creative character and its ability to transform society.

Now we have the struggle of the Indigenous people in Ecuador and in Bolivia. We believe in communal socialism. Others believe in Vivir Bien and it would be absurd to try to counterpose those projects. When we talk about them, we can only describe them in broad terms. There is not only one universal class system. This is what Marx thought. This is not the fault of Marx because he thought the world would develop like this. He did analyse the underdeveloped countries, but this society was at the periphery.

We are in an extraordinary time in Latin America because we are advancing from a stage where some of us have taken power, but also where there are strong social movements. At present, not all the people have their own governments. There are states where people don’t have a revolutionary government, but they are advancing, like Argentina, Brazil, the students in Chile, outside of the state.

It’s clear that our revolutionary processes in Bolivia, Venezuela and Ecuador will not advance unless they go forward in their internal struggles, in the strength of their peoples’ movements. Because we have to live in this world, whether we like it or not. The progressive governments of Cristina Kirchner de Fernandez in Argentina and the government of Brazil are also helping us advance. We know that these governments have profound internal contradictions in their societies, not just the same as ours. Without us though, there would also be a problem for them. They would have worse governments. But internationally, they have constructed a geopolitics which is marking out a clear separation from the USA. We could say that Latin America is “Latin Americanising” and emerging in its own right. Our fight against imperialism is important. ALBA has had a greater political impact than in creating new models of trade. Still, ALBA is making improvements. ALBA is an alternative mechanism of integration, although as a commercial and economic unit, I still think it is limited. But then ALBA as a symbol and example of correct policy is worth far more than as a mechanism for commercial exchange. Without ALBA, there would be no community of Latin America and the Caribbean; without ALBA there would be no UNASUR. Therefore ALBA is playing an important role.

What is your vision of the future of Bolivia in the next decade?

We don’t know what is going to happen. All we know is that, each day, Latin America and Bolivia are in the struggle. Each day, we don’t know if we are going to live or die tomorrow. We are confronting the most powerful imperialism in the world. Capitalism is growing and I do not want to say it is dead.

Today, capitalism is carrying out a new wave of colonising the world. It is beginning in Africa and in part of Asia and for this reason Bolivia and other countries have had some relief.

Capitalism is creating new forms of primitive accumulation. They are “accumulating by dispossession”. Where are the great natural resources today in the world? Latin America and Africa. The imperialists are invading Africa directly, militarily. They are not doing this to us so far. But I don’t want to say they will not do it. The majority of drinkable water is in Latin America and the US needs fresh water. The greatest reserves of lithium, the forests, the plants that produce oxygen, the best medicinal plants and the sources of biodiversity are in Latin America.

Imperialism is starting in Africa, but they want to get back into Latin America. How many people are aware of this? Very few. We don’t know what would happen in Latin America if the imperialists began an invasion. Fortunately, we have a bit of time.

What is your message to Australians and the need for international solidarity with Bolivia and the rest of Latin America?

In the 20th century, Latin America followed the example of the struggles of the people of Europe, the socialist countries of Europe. With this experience in mind, what can we say? Develop all possible forms of solidarity with Bolivia, Venezuela and Ecuador, and with Latin America in general. Latin America is a laboratory of struggles. I don’t want to say merely follow our example because it would be an act of pedantry. To think that Latin America has the solution for the whole world: that is what we thought about the Soviet Union.

You have to struggle as well. Everybody has to fight against capitalism all over the world. Your struggle, wherever possible in the circumstances of Australia, will help the process in Latin America. In military terms, the enemy is currently distracted from its goal. The enemy right now is concentrating its forces in Africa and Latin America. If Europe fights and the Australian continent fights, this also will favour us. Because it obliges the enemy to focus on other problems besides us.

Note

[1] The Morales candidate lost, but increased the vote for MAS.

Bolivia's future

silver and tin don’t have the economic importance they had in times past. Zinc has taken to the forefront among the Altiplano’s main mineral exports. Despite Bolivia’s treasury savings, this hasn’t been enough to absorb the risks of mining and since 1985 the country’s governments haven’t done much to encourage the development of private mining, as might be expected. great info!