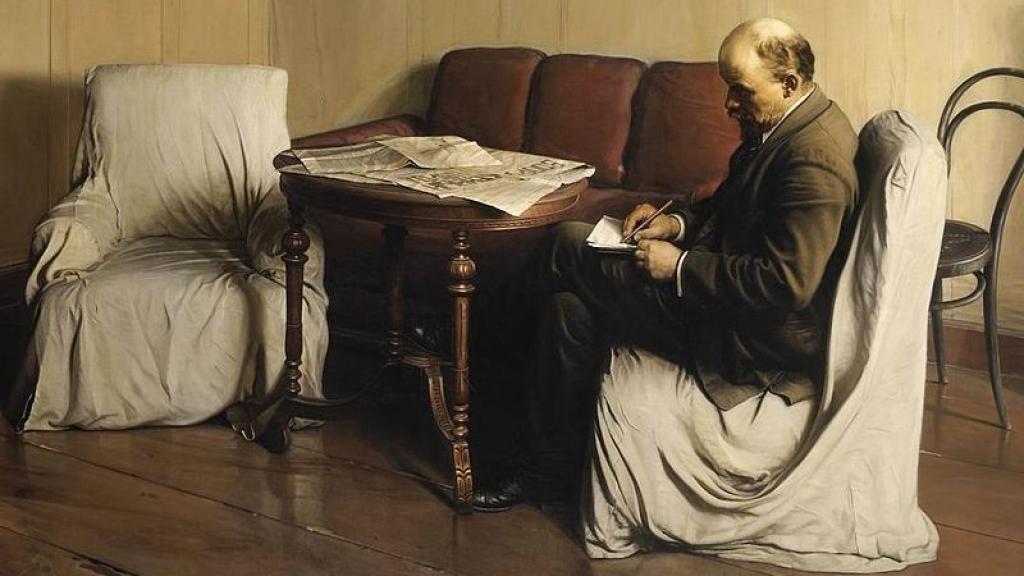

In defence of Lenin’s writings on the national question: A response to Hanna Perekhoda

Hanna Perekhoda’s reading of Vladimir Lenin’s pre-1913 writings on the national question is not merely tendentious; it constructs a caricature that reduces Lenin to a great Russian imperialist, cynically wielding the rhetoric of self-determination as a lure for non-Russian leftists. Perekhoda’s depiction is not unique but rather reflects a broader trend in modern Ukrainian historiography, which frequently portrays Lenin as an imperialist “opportunist”, an internationalist in name only, and a staunch opponent of Ukrainian independence.

This interpretation stands in stark contrast to how Lenin is perceived in contemporary Russia, where he is alternatively condemned as the architect of the Soviet Union’s fragmentation or, paradoxically, blamed for having created modern Ukraine. These conflicting narratives reached their most concentrated expression in Russian President Vladimir Putin’s speech on February 21, 2022, delivered on the eve of Russia’s “Special Military Operation” in Ukraine.

How is it that Lenin’s views and actions can be interpreted in such diametrically opposed ways in modern Russia and Ukraine? Anthony Smith observed that nationalist historiography is not merely an academic endeavour but an active political process that selectively reinterprets the past to legitimise present aspirations. Competing national histories emerge from this dynamic: in Ukraine, a narrative of uninterrupted imperial subjugation by Russia (and the Soviet Union); in Russia, the portrayal of Ukraine as an artificial construct devoid of historical legitimacy. Both seek to present their respective national identities as timeless and authentic.

Writing about modern Ukrainian historiography, prominent Ukrainian historian Georgiy Kasyanov stressed that “the promotion of (new) ideological constructs in post-Soviet Ukraine often contradicted some of the fundamental rules and procedures of history as a scientific discipline. However, at the same time, it perfectly fit the ideological and political demand of a section of the ruling class and also met the expectations of part of society, which sought explanations for life’s problems and challenges in the presented version of events…” Kasyanov concludes, “It appeared as if the historians were on a mission.”

The same can be said about modern Russian historiography. The events of the past are selectively reinterpreted to serve present-day ideological objectives. These tendentious readings and depictions of Lenin may have little to do with what Lenin actually thought and instead function as instruments of contemporary politics, shaping historical memory in ways that align with the needs of the ruling classes.

Methodological flaws in Perekhoda’s analysis

At the centre of Perekhoda's analysis is the difference in views of Lenin and his contemporary, Ukrainian Social Democrat Lev Yurkevych, on the treatment of minorities in the party program. Although Perekhoda claims this polemic has been largely forgotten, given “the Russian Communist Party’s deliberate efforts to erase dissident voices and the Western public’s longstanding attachment to the perspectives of the Russian imperial centre,” in reality, this polemic is well known because it has been preserved for us by none other than Lenin himself. In his work Critical Remarks on the National Question, Lenin provides a detailed Marxist critique of Yurkevych’s views, which Perekhoda now uses to critique Lenin himself.

Perekhoda’s critique of Lenin suffers from four fundamental methodological flaws:

- it fails to situate Lenin’s national policy in historical context, isolating Lenin’s statements from their concrete historical conditions;

- it applies a selective and decontextualised readings of Marxist thought, isolating statements while ignoring their broader theoretical and political context;

- it misrepresents Lenin’s debates with opponents by ignoring the totality of these debates and omitting important elements that contradict her conclusions; and, finally,

- it misframes the Bolshevik national policy as imperialist by failing to account for the strategic imperatives that shaped Bolshevik policy.

Failure to situate Lenin’s national policy in historical context

A major deficiency in Perekhoda’s methodology is her failure to situate Lenin’s national policy within its historical development. Lenin insisted — both in his polemic with Rosa Luxemburg and elsewhere — that concrete historical analysis is the essence of the Marxist approach. Perekhoda disregards this principle by treating Lenin’s pre-1913 discussions on the national question as if they had been eternal and immutable, without considering the specific historical context.

The discussions with Yurkevych she uses to unmask Lenin as a “secret Russian imperialist” were conducted in the context of the Bolshevik Party’s pre-revolutionary program, formulated within a Tsarist empire that was still intact. At that stage, Lenin and the Bolsheviks advocated the right to national self-determination primarily as a means to break the grip of Russian absolutism and mobilise the working class against Tsarism. This position was part of the broader Bolshevik strategy of establishing a democratic (bourgeois) republic as a necessary step toward a proletarian revolution.

Selective and decontextualised readings of Marxist thought

A highly selective use of Lenin’s writings, which isolates specific statements while ignoring the broader theoretical and political framework in which they were formulated, results in a misrepresentation of his views on the national question. Lenin’s strategy was never static; it adapted to shifting historical conditions. To borrow Eric Hobsbawm’s description of Karl Marx’s work, Lenin’s thought was, like all thought that deserves the name, an endless work in progress. Perekhoda, however, misrepresents Lenin’s view as fixed ideological commitments rather than historically contingent strategic positions.

Such selective interpretation can be seen in other debates on Marxist thought. For example, Branko Milanovic, in Visions of Inequality, argues that Marx was not an egalitarian thinker — at least not in the sense of advocating for reduced inequality within capitalism. Milanovic points out that for Marx, the question of reducing inequality under capitalism was largely irrelevant, much like discussing political equality under slavery. In Marx’s view, economic redistribution within capitalism could be a means of mobilising workers and raising their class consciousness, but it was never the final objective. The ultimate goal was always the abolition of class society itself. This point is especially evident in Critique of the Gotha Program, where Marx critiques reformist demands for equality within capitalism as insufficient. But such an interpretation is incomplete as it fails to distinguish between Marx’s critique of capitalist equality and his vision of full social equality in a communist society.

In her methodological approach, Perekhoda applies a selective reading to Marx and Friedrich Engels, singling out only one aspect of their work — the eventual withering away of nations under communism. In doing so, she ignores the varied views and practical solutions offered by the founders of Marxism, including a federal republic as a “step forward” under certain conditions. Analysing their views in The State and Revolution, Lenin remarks:

Although mercilessly criticizing the reactionary nature of small states, and the screening of this by the national question in certain concrete cases, Engels, like Marx, never betrayed the slightest desire to brush aside the national question.

Perekhoda applies a similar method of decontextualisation to Lenin. She seizes on pre-1913 statements on national self-determination but fails to account for how Lenin’s position evolved in the wake of the revolution, when national policy became a pressing issue in the governance of a multi-ethnic socialist state. Just as an incomplete reading of Marx could falsely portray him as indifferent to equality, Perekhoda’s selective treatment of Lenin presents him as a consistent proponent of Russian domination, ignoring his later struggle against Great Russian chauvinism and the policies of korenizatsiya.

Misrepresentations of Lenin’s debates with opponents

Furthermore, while Perekhoda briefly engages with Luxemburg and Austrian Marxism (Otto Bauer), her comparative analysis remains superficial. She focuses on Lenin’s rejection of Bauer’s concept of cultural autonomy, framing this not as a principled Marxist stance but as evidence of Lenin’s supposed imperialist tendencies. However, she fails to fully contextualise why Lenin opposed cultural autonomy and how his position on national self-determination differed from Bauer’s.

Bauer’s emphasis on “cultural-national autonomy,” with its implied recognition of the equality of all cultures, was certainly welcome. But the main problem with the Austro-Marxists was that the political perspective they offered was quite inadequate for their times. In the context of the existing Tsarist Empire, Bauer called for civil equality and federation within the Empire rather than the overthrow of Tsarist rule (tellingly, he also rejected autonomy for Jews in the Austro-Hungarian Empire). This had direct organisational implications. In contrast to Lenin’s effort to build a more centralised party structure as a fighting instrument — whether operating underground or openly — Bauer’s perspective called for a much more loosely bound federated structure, since overthrowing the Tsarist state was not supposed to be on the current agenda. Moreover, as Achin Vanaik notes, cultural-national autonomy was not a substitute for the much more democratic call for respecting the “right to self-determination” that Lenin would put forward.

At the same time Lenin did not advocate rigid centralisation at the expense of national autonomy. He addressed this directly in Critical Remarks on the National Question (although Perekhoda preferred not to notice it):

It is beyond doubt that in order to eliminate all national oppression it is very important to create autonomous areas, however small, with entirely homogeneous populations, towards which members of the respective nationalities scattered all over the country, or even all over the world, could gravitate, and with which they could enter into relations and free associations of every kind. All this is indisputable, and can be argued against only from the hidebound, bureaucratic point of view.

He drew on Engels’ arguments to assert that centralisation does not exclude local freedoms and that democratic governance could accommodate both. Addressing those who feared that autonomy would weaken the democratic state, Lenin argued in a letter to S. G. Shahumyan in 1913 (the same year he wrote Critical Remarks on the National Question, much criticised by Perekhoda):

Recall Engels’s explanation that centralisation does not in the least preclude local “liberties”. Why should Poland have autonomy and not the Caucasus, the South, or the Urals? ... We are certainly in favour of democratic centralism. We are opposed to federation... But to be afraid of autonomy in Russia of all places—that is simply ridiculous! It is reactionary. Give me an example, imagine a case in which autonomy can be harmful. You cannot. But in Russia (and in Prussia), this narrow interpretation—only local self-government—plays into the hands of the rotten police regime.

Remarkably, Perekhoda refers to the same letter as evidence of Lenin’s “firm rejection of any calls for federalism or autonomy.” However, this passage demonstrates that Lenin was not advocating Russian dominance but rather an adaptable and democratic form of governance, where regional and national autonomy was a natural component of a democratic state. His opposition to federation was not an opposition to national self-rule but rather a rejection of a weak and fragmented political structure that would prevent the proletariat from effectively exercising power.

Misframing Bolshevik national policy as imperialist

Another of Perekhoda’s methodological flaws is her failure to properly contextualise the debates on the national question within Ukrainian Social Democracy itself. She treats Yurkevych as the representative of Ukrainian Social Democracy, presenting his views as the dominant perspective within the movement. However, this is a highly selective portrayal that distorts the internal debates among Ukrainian Marxists.

In reality, Yurkevych’s views were far from dominant. Many leading figures in Ukrainian Social Democracy — including Aleksandr Khmelnitsky, Nikolay Skripnik, and Vladimir Zatonsky — shared Lenin’s position that splitting the party and the proletariat into autonomous national groups was a betrayal of the cause of working-class liberation. These figures argued that a unified proletarian movement was needed to overthrow capitalism, and that ethnic fragmentation of the working class only served to weaken its revolutionary potential. Perekhoda’s failure to acknowledge these debates creates the false impression that Yurkevych’s critique of Lenin was the consensus view when, in fact, many Ukrainian Social Democrats rejected his position in favour of Lenin’s internationalist approach.

Perekhoda also misrepresents the strategic imperatives that shaped Bolshevik national policy. The Bolsheviks were not imposing Russian domination but were attempting to hold together a multinational working-class movement in the face of growing nationalist fragmentation. Lenin’s national policy was guided by the need to win the allegiance of non-Russian workers, not by an imperialist desire to maintain a Russian-dominated state. In Lenin’s view, Russian capitalists and landowners were as much the enemy of the Ukrainian worker as they were of the Russian worker. Hence, the common struggle was a necessity, not a means of enforcing Russian cultural or political hegemony. Lenin’s position on the national question was rooted in class unity and revolutionary strategy, not in any imperialist logic. Perekhoda’s failure to analyse these political constraints leads her to falsely equate Lenin’s position with imperialist expansionism, ignoring the fundamental differences between capitalist national assimilation and the socialist approach to national self-determination.

Lenin’s ‘imperialist sins’: Perekhoda’s attempt to ‘decolonise’ Lenin

Perekhoda’s critique of Lenin as an imperialist figure lacks a clear definition of imperialism itself, making her argument ultimately superfluous. However, she does offer an implicit definition of imperialism as a predominantly cultural phenomenon — one characterised by the domination and subjugation of local cultures by a dominant culture and ideology. She does not engage with the classic Marxist definition of imperialism as a system of economic domination, whereby the imperialist centre extracts surplus value from the periphery through economic, political, and military coercion.

In effect, Perekhoda’s approach is indistinguishable from the definition of Russian imperialism formulated by the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory in the Ukrainian Law On the Condemnation and Prohibition of Propaganda of Russian Imperial Policy in Ukraine and the Decolonisation of Toponymy (2023). Also known as the Law on Decolonisation, it defines Russian imperial policy as

systemic activities, which in different historical periods, starting from the Moscow Tsardom and to the present Russian Federation, have been directed to subjugation, exploitation, [and] assimilation of the Ukrainian people. Its component is Russification, that is, the imposition of the Russian language and the propaganda of the Russian language and culture as superior to other languages and cultures.

Perekhoda adopts this cultural concept of imperialism because she is uncritically led by Yurkevych’s nationalist critique of Lenin. She makes no attempt to critically assess Yurkevych’s claims, which is a significant methodological flaw. The mere fact that Yurkevych originated from the periphery (of the Russian Empire) does not make his arguments inherently correct or superior to Lenin’s position. By failing to interrogate Yurkevych’s perspective, Perekhoda falls into the trap of equating national grievances with a sound historical-materialist critique — an assumption that remains unexamined in her work.

As a result, her treatment of imperialism becomes indistinguishable from the accusations made by the most reactionary nationalist forces in Ukraine, who seek to eradicate any and all traces of Russian or Soviet culture. This approach reduces a complex historical and political process to a simplistic cultural confrontation, overlooking the materialist foundations of Lenin’s policies and their revolutionary intent.

The core of her argument revolves around four key issues, largely fixated — like ethno-nationalist critiques — on Russian culture and language:

- Lenin allegedly promoted cultural imperialism by encouraging the education of Ukrainians in Russian and exposure to Russian culture, thereby undermining Ukrainian national identity and promoting assimilation;

- By advocating for proletarian unity and emphasising economic integration, Lenin supposedly marginalised Ukrainian national aspirations, driving a wedge between the Russified working class and the Ukrainian peasant mass;

- Lenin further entrenched Russian imperialism by advocating for large and economically integrated states under the pretext of economic efficiency, which Perekhoda equates with a continuation of the Russian imperial project and a negation of Ukrainian statehood;

- The Bolsheviks adopted an authoritarian approach by claiming a unique ability to interpret historical necessity, thereby granting themselves the authority to determine the legitimacy of national liberation struggles, disregarding the agency of the population; and

- Finally, Lenin, along with other Marxists, envisioned the eventual withering away of national distinctions, which Perekhoda portrays as a deliberate underestimation of the importance of national cultures within the socialist project, leading to the erosion of Ukrainian national identity.

By framing these positions as evidence of Lenin’s complicity in imperialism, Perekhoda reduces a complex historical and political strategy to an ideological caricature, neglecting the broader revolutionary objectives that shaped Bolshevik policy on national self-determination.

Lenin and the alleged Russification of Ukrainians

The claim that Lenin promoted cultural imperialism by encouraging the education of Ukrainians in Russian and exposing them to Russian culture distorts his actual position. Lenin was a staunch opponent of Great Russian chauvinism.

Lenin explicitly rejected the forced assimilation of oppressed nationalities. His commitment to national self-determination included the right of nations to develop their own languages and cultures. In Thesis on The National Question, he wrote:

Social-Democrats, in upholding a consistently democratic state system, demand unconditional equality for all nationalities and struggle against absolutely all privileges for one or several nationalities. In particular, Social-Democrats reject a “state” language.

Perekhoda argues that Lenin’s commitment to language equality and opposition to national domination was merely a tactical manoeuvre, a ruse designed to lure non-Russian nations into the class struggle. However, Lenin’s writings reveal that his stance was not an opportunistic strategy but a deeply held principle. A passage from One Step Forward, Two Steps Back (written in 1904, almost 10 years before Lenin’s polemic with Yurkevych) underscores Lenin’s principled rejection of Russification:

Another of its spokesmen, the Mining Area delegate Lvov, who stood close to Yuzhny Rabochy, declared that “the question of the suppression of languages which has been raised by the border districts is a very serious one. It is important to include a point on language in our programme and thus obviate any possibility of the Social-Democrats being suspected of Russifying tendencies.” A remarkable explanation of the “seriousness” of the question. It is very serious because possible suspicions on the part of the border districts must be obviated! The speaker says absolutely nothing on the substance of the question, he does not rebut the charge of fetishism but entirely confirms it, for he shows a complete lack of arguments of his own and merely talks about what the border districts may say. Everything they may say will be untrue he is told. But instead of examining whether it is true or not, he replies: “They may suspect.”

Lenin does not argue that socialists should merely avoid the appearance of Russification to maintain credibility with non-Russian nations; rather, he insists that the movement must eliminate any basis for such suspicions by maintaining a clear and unequivocal commitment to linguistic and national equality, because this is the only right thing to do. Lenin’s critique here is directed at those within the socialist movement who treated concerns about national oppression as secondary or as issues to be managed for the sake of appearances rather than confronted as matters of fundamental principle.

Furthermore, Lenin directly opposed the idea that Russian should be the sole language of instruction. In Critical Remarks on the National Question, he stated:

The national programme of working-class democracy is: absolutely no privileges for any one nation or any one language...

Moreover, Lenin explicitly addressed similar accusations made by Yurkevych:

Mr. Lev Yurkevich acts like a real bourgeois, and a short-sighted, narrow-minded, obtuse bourgeois at that, i.e., like a philistine, when he dismisses the benefits to be gained from the intercourse, amalgamation and assimilation of the proletariat of the two nations, for the sake of the momentary success of the Ukrainian national cause (sprava). The national cause comes first and the proletarian cause second, the bourgeois nationalists say... The proletarian cause must come first, we say, because it not only protects the lasting and fundamental interests of labor and of humanity, but also those of democracy; and without democracy, neither an autonomous nor an independent Ukraine is conceivable.

Perekhoda misinterprets Lenin’s use of the term “assimilation” (Lenin sarcastically called it “the nationalist bogey of ‘assimilation’”) in Critical Remarks on the National Question. Lenin did not advocate for Ukrainians to be assimilated into the Russian nation; rather, he used the term to describe the overcoming of nationalist divisions between Ukrainian and Russian workers. He wrote:

But it would be a downright betrayal of socialism and a silly policy even from the standpoint of the bourgeois “national aims” of the Ukrainians to weaken the ties and the alliance between the Ukrainian and Great-Russian proletariat that now exist within the confines of a single state.

Lenin’s primary concern before 1917 was ensuring proletarian unity in the struggle against capitalism, not erasing Ukrainian national identity. As the political situation in Russia evolved, the immediate threat to working-class unity receded, and the practical challenges of state-building became more prominent. In response, Lenin further refined his position to incorporate the idea of federation. Writing in 1918, he made this position explicit:

We stand for democratic centralism. Opponents of centralism constantly put forward autonomy and federation as means to counteract the contingencies of centralism. In reality, democratic centralism in no way excludes autonomy; on the contrary, it presupposes its necessity. Even federation, if implemented within reasonable economic limits and based on significant national differences that create a genuine need for a certain degree of state distinctiveness, does not contradict democratic centralism in the slightest.

Lenin envisioned a political structure in which nations retained their distinctiveness while maintaining a unified revolutionary movement. His insistence on a supranational framework — eventually realised in the Soviet Union — was based on the principle that all national groups should enjoy equal rights and have space to develop their cultures.

Perekhoda oversimplifies Lenin’s position on culture, portraying it as purely utilitarian. In reality, Lenin had a nuanced understanding of culture, recognising that all cultures contained both progressive and reactionary elements. He argued workers should absorb and integrate the most advanced elements from all national cultures, rather than subordinating one to another.

The accusation that Lenin promoted cultural imperialism by encouraging the education of Ukrainian workers in Russian and exposing them to Russian culture distorts his actual stance on national self-determination, language policy and proletarian unity. Lenin’s position was never about assimilating Ukrainians into Russian culture, but about overcoming nationalist divisions within the working class to strengthen the socialist movement.

Lenin distinguished between the progressive and regressive elements in national cultures. He was highly critical of reactionary elements within Russian culture, particularly its chauvinistic and imperialist tendencies, which deserved contempt and disgust. He wrote in On the National Pride of the Great Russians in 1914:

We especially hate our servile past — when landlords and nobles led the peasants to war to crush the freedom of Hungary, Poland, Persia, and China — and our servile present, when those same landlords, now allied with the capitalists, lead us into war to suppress Poland and Ukraine… No one is to blame for being born a slave; but a slave who not only shuns the desire for freedom but also justifies and embellishes his own servitude — who, for instance, calls the suppression of Poland and Ukraine a “defence of the Great Russian fatherland” — such a slave is nothing more than a servile lackey, deserving of rightful indignation, contempt, and disgust.

Does not this damning characterisation of Russian imperialism sound remarkably contemporary as if written today?

Lenin saw value in the progressive elements of other national cultures, including Ukrainian culture, which he believed Russian workers should engage with to enrich their own. His approach was not about the “subjugation” or replacement of one national culture by another but about fostering a complex exchange of progressive ideas across national lines. In his work Concerning an Article Published in the Organ of the Bund where Lenin notes that the newspaper of Russian Social-Democrats Proletary, operating under the conditions of an illegal enterprise, is deprived of the ability to properly follow the Social-Democratic organs published in Russia in languages other than Russian, calls on

... all comrades who know Lettish, Finnish, Polish, Yiddish, Armenian, Georgian or other languages, and who receive Social-Democratic newspapers in these languages, to help us to keep Russian readers informed about the state of the Social-Democratic movement and the views of the non-Russian Social-Democrats on tactics.

This perspective is also evident in his stance on national education. Lenin defended the development of national languages, national education and other national rights, as long as they did not become tools of bourgeois nationalism that divided the working class. Writing four years before the October 1917 revolution, Lenin warned in the Critical Remarks on the National Question about that danger of bourgeois capitalism, using a stern language against Yurkevych:

If a Ukrainian Marxist allows himself to he swayed by his quite legitimate and natural hatred of the Great-Russian oppressors to such a degree that he transfers even a particle of this hatred, even if it be only estrangement, to the proletarian culture and proletarian cause of the Great-Russian workers, then such a Marxist will get bogged down in bourgeois nationalism. Similarly, the Great-Russian Marxist will be bogged down, not only in bourgeois, but also in Black-Hundred nationalism, if he loses sight, even for a moment, of the demand for complete equality for the Ukrainians, or of their right to form an independent state.

Writing four years after the Critical Remarks on the National Question, Lenin unequivocally condemned the imperialist policy of Russification in Ukraine, which denied Ukrainian children the right to speak and learn in their own language:

Accursed tsarism made the Great Russians executioners of the Ukrainian people, and fomented in them a hatred for those who even forbade Ukrainian children to speak and study in their native tongue.

This passage shows that Lenin distinguished between language as an instrument of class struggle and a medium of national culture. There was no contradiction between using the Russian language as a means to advance the cause of the Ukrainian proletariat and the use of the Ukrainian language for education and communication starting from the earliest age.

Perekhoda’s argument fails to acknowledge these key elements of Lenin’s policy. Rather than imposing Russian language and culture on Ukrainians, Lenin sought to dismantle the structures of national oppression inherited from the Tsarist Empire. His policies supported national equality, and his writings consistently called for the elimination of all forms of linguistic and cultural coercion. Lenin’s position, therefore, contradicts the assertion that he promoted Russification.

Proletarian unity or national marginalisation? Lenin’s position on Ukraine

Perekhoda contends that Lenin, by prioritising proletarian unity and economic integration, effectively marginalised Ukrainian national aspirations, driving a wedge between the Russified urban working class and the predominantly Ukrainian peasant masses. However, this claim misrepresents Lenin’s position, which did not negate Ukrainian national liberation but rather sought to ground it in class struggle.

In his Critical Remarks on the National Question, Lenin directly addressed the argument put forth by Ukrainian socialists such as Yurkevych. He identified the primary antagonists of Ukrainian liberation as the Great-Russian and Polish landlord class, along with the bourgeoisie of these two nations, and argued that only the proletariat — Ukrainian and Great-Russian together — could provide the social force necessary to overcome these reactionary elements. His conclusion was clear: “Given united action by the Great-Russian and Ukrainian proletarians, a free Ukraine is possible; without such unity, it is out of the question.”

Rather than subordinating Ukrainian national aspirations to Russian proletarian interests, Lenin emphasised that the struggle for socialism inherently contained the conditions for genuine national liberation. He made a sharp distinction between bourgeois nationalism — whether Russian or Ukrainian — and the proletarian struggle, arguing that the latter was the only viable means of achieving not only national self-determination but also the broader emancipation of the oppressed peasantry.

Lenin emphatically rejected the idea that advocating proletarian unity meant disregarding the linguistic and cultural dimensions of class struggle. He explicitly affirmed the necessity of engaging the peasantry in their native language, arguing in Critical Remarks on the National Question:

No democrat, and certainly no Marxist, denies that all languages should have equal status, or that it is necessary to polemise with one’s “native” bourgeoisie in one’s native language and to advocate anti-clerical or anti-bourgeois ideas among one’s “native” peasantry and petty bourgeoisie. That goes without saying, but the Bundist uses these indisputable truths to obscure the point in dispute, i. e., the real issue.

In his Draft Resolution on the Place of the Bund in the Russian Social-Democratic Party seven years earlier (in 1906), Lenin made it explicit that organisational unity in no way restricted national-specific forms of agitation:

that the complete amalgamation of the Social-Democratic organisations of the Jewish and non-Jewish proletariat can in no respect or manner restrict the independence of our Jewish comrades in conducting propaganda and agitation in one language or another, in publishing literature adapted to the needs of a given local or national movement, or in advancing such slogans for agitation and the direct political struggle that would be an application and development of the general and fundamental principles of the Social-Democratic programme regarding full equality and full freedom of language, national culture, etc., etc.;

This principle applied just as much to Ukrainian Social Democrats as it did to Jewish Social Democrats. Lenin’s insistence on party unity did not mean imposing Russian as the sole language of political work but rather ensuring that national forms of agitation developed within a broader socialist framework. His approach was therefore not one of cultural Russification or forced integration but of ensuring that Ukrainian self-determination was not confined to the bourgeois-led aspirations of nationalists but was instead linked to the broader socialist transformation.

Crucially, Lenin rejected the notion that proletarian unity necessitated the suppression of national aspirations. In The Right of Nations to Self-Determination, he explicitly reaffirmed Ukraine’s right to independence, arguing that educating the working class in socialist internationalism was fully compatible with upholding national aspirations:

Whether the Ukraine, for example, is destined to form an independent state is a matter that will be determined by a thousand unpredictable factors. Without attempting idle “guesses”, we firmly uphold something that is beyond doubt: the right of the Ukraine to form such a state. We respect this right; we do not uphold the privileges of Great Russians with regard to Ukrainians; we educate the masses in the spirit of recognition of that right, in the spirit of rejecting state privileges for any nation.

Beyond party structures, Lenin’s commitment to national equality extended to the legal and institutional framework of the democratic state. He insisted that the national program of workers’ democracy must include a statewide law explicitly prohibiting any action that grants privileges to one nation over another or violates the equality of nations and the rights of national minorities:

... the promulgation of a law for the whole state by virtue of which any measure (rural, urban or communal, etc., etc.) introducing any privilege of any kind for one of the nations and militating against the equality of nations or the rights of a national minority, shall be declared illegal and ineffective, and any citizen of the state shall have the right to demand that such a measure be annulled as unconstitutional, and that those who attempt to put it into effect be punished.

Such a policy would have rendered any discriminatory state action — including any privileging of Russian language or culture — both unconstitutional and subject to legal penalties. Lenin’s approach thus went far beyond rhetorical commitments to equality; it sought to institutionalise national parity within the legal framework of the socialist state.

The claim that Lenin’s policies alienated the Ukrainian peasantry disregards his strategic focus on forging an alliance between the working class and the democratic peasantry. The early Soviet land policies, including the redistribution of land from landlords to peasants, gained mass support among Ukrainian peasants, despite later reversals under Josef Stalin. The suppression of Ukrainian national expression and the forced collectivisation of the 1930s were a direct betrayal of Lenin’s approach, not its fulfilment.

By conflating Lenin’s commitment to proletarian unity with a dismissal of Ukrainian national aspirations, Perekhoda misinterprets both his theory and historical practice. Far from marginalising Ukraine, Lenin’s framework provided the only path for its true liberation — one grounded in class struggle rather than elite-driven nationalism.

Economic integration and imperialism: Lenin’s perspective

Perekhoda argues that Lenin entrenched Russian imperialism by advocating for large and economically integrated states under the pretext of economic efficiency, equating this with a continuation of the Russian imperial project and a negation of Ukrainian statehood. However, this interpretation distorts Lenin’s position by failing to distinguish between economic integration under capitalism and economic integration as a stage in the development of social forces that would ultimately overthrow capitalism.

Lenin, following Marx and Engels, viewed capitalist development as a necessary but transient historical phase. He recognised that smaller states often lagged in capitalist development, retaining pre-capitalist and feudal features for longer periods. His emphasis on large-scale economic integration was not rooted in a desire to sustain capitalism, but rather in the belief that capitalism’s accelerated development would create the conditions for a revolutionary working class capable of dismantling it. What Perekhoda mistakes for Lenin’s “capitalist” focus on abstract economic efficiency was, in fact, a focus on the optimal conditions for the growth of the social forces that would eventually deliver a death blow to capitalism.

Accusing Lenin of “economism,” Perekhoda revives the old claim that his perspective implicitly supported Russification. She argues that Lenin, by applying a free-market logic to the socio-cultural sphere, downplayed the coercive aspects of language assimilation. Specifically, she cites Lenin’s statement that Social Democrats should seek to eliminate privileges for all languages, allowing “the requirements of economic exchange to determine which language in a given country it is to the advantage of the majority to know for the sake of commercial relations.” Yurkevych countered that the Russification of Ukrainians was not the outcome of free individual choice but rather the product of colonial expansion, uneven economic development between urban and rural areas, and political and economic coercion.

However, these accusations of economism reflect a fundamental misunderstanding of Marxist theory: they fail to appreciate that economic reality ultimately defines the character of social institutions. Ignoring economic reality comes at a hefty cost. Contrary to Perekhoda’s claims, Lenin did not dismiss the issue of language suppression, nor did he argue that the deliberate obstruction of minority languages “presented no issue”.

Rather, he recognised that economic conditions shape linguistic dynamics. Given the close economic integration between Russia and Ukraine at the time, Russian was the practical choice for economic interaction. However, Lenin never treated this as an immutable condition. He explicitly stated in the Critical Remarks on the National Question that linguistic dynamics would shift if Ukraine became independent and economic exchanges with Russia diminished. This principle is evident today in Ukraine’s own language policies. The recent Ukrainian Law on English, which consolidates English as a language of international communication and mandates its study from early education, reflects the same economic logic Lenin outlined. Yet, no voices in Ukraine or the West argue that the “Englishification” of Ukraine signals imperialist domination — illustrating the selective application of Perekhoda’s reasoning.

Crucially, Lenin’s stance on economic integration was not imperialist, either in the economic or cultural sense. His framework was limited strictly to the development of capitalism, not its preservation. If Lenin had been advocating for Russian imperialism under the guise of economic efficiency, he would not have consistently defended the right of Ukraine and other nations to self-determination, autonomy or (later) federation. Even within The Critical Remarks on the National Question, where he analysed the economic and political logic of national movements under capitalism, Lenin mentioned an independent Ukraine five times, demonstrating that his approach was neither dismissive of national aspirations nor subordinated to a Russian imperial project.

Moreover, Lenin’s position evolved alongside the growth of the working-class movement in the Russian Empire and the rise of democratic and socialist struggles. Formulating the tasks of the proletariat just four months before the October 1917 Revolution, Lenin emphasised both the unconditional realisation of the right of secession and the party’s strive for a large state based on a “free fraternal union” and with the “broadest local (and national) autonomy” and “elaborate guarantees of the rights of national minorities” — in other words, everything Perekhoda claims was rejected or ignored by Bolsheviks.

As regards the national question, the proletarian party first of all must advocate the proclamation and immediate realisation of complete freedom of secession from Russia for all the nations and peoples who were oppressed by tsarism, or who were forcibly joined to, or forcibly kept within the boundaries of, the state, i.e., annexed... The proletarian party strives to create as large a state as possible, for this is to the advantage of the working people; it strives to draw nations closer together, and bring about their further fusion; but it desires to achieve this aim not by violence, but exclusively through a free fraternal union of the workers and the working people of all nations... Complete freedom of secession, the broadest local (and national) autonomy, and elaborate guarantees of the rights of national minorities—this is the programme of the revolutionary proletariat.

Just two months later, in November 1917, Lenin explicitly rejected the imperialist legacy of Tsarist Russia and embraced full Ukrainian self-determination. In one of his first statements following the revolution, he declared:

... we stand unconditionally for the Ukrainian people’s complete and unlimited freedom. We have to wipe out that old bloodstained and dirty past when the Russia of the capitalist oppressors acted as the executioner of other peoples. We are determined to wipe out that past, and leave no trace of it.

We are going to tell the Ukrainians that as Ukrainians they can go ahead and arrange their life as they see fit. But we are going to stretch out a fraternal hand to the Ukrainian workers and tell them that together with them we are going to fight against their bourgeoisie and ours. Only a socialist alliance of the working people of all countries can remove all ground for national persecution and strife.

Much later, on the eve of the formation of the Soviet Union in 1922, far from encouraging Russification under the pretext of a large and economically integrated state, Lenin insisted on “the strictest rules must be introduced on the use of the national language in the non-Russian republics of our union,” emphasising that these rules must be checked with special care. He also warned about the danger of a “mass of truly Russian abuses” on the pretext of unity in the railway service, in the fiscal service and so on. Lenin insisted on uncompromising struggle against these abuses, not to mention special sincerity on the part of those who undertake this struggle.

These statements are antithetical to any imperialist project, demonstrating that Lenin’s support for economic integration was not a mechanism for Russian dominance, but rather a step toward socialist internationalism. His approach to Ukraine — and to all national movements — was always framed within the broader goal of worker-led self-determination and voluntary socialist unification. Lenin rejected the idea that socialism could be imposed through coercion and explicitly denounced any attempt to restore the oppressive structures of Tsarist Russia under a socialist banner.

Perekhoda’s argument rests on a fundamental misunderstanding of Lenin’s economic framework. His emphasis on large-scale economic integration was not a means of justifying imperialist expansion, but rather a recognition that capitalism, by its very nature, created a common economic base from which the proletariat could unite against their exploiters. His advocacy of economic efficiency was always subordinate to the principle of voluntary national self-determination and the ultimate goal of socialist transformation.

The Bolsheviks’ supposed authoritarianism and historical determinism

Perekhoda grossly misrepresents the essence of the Summer 1913 Conference Resolution on the National Question. Contrary to her claim that Lenin and the Bolsheviks rejected the concept of “national autonomy,” the resolution explicitly affirms complete equality and cultural, educational, and self-rule autonomy for all ethnic groups:

Insofar as national peace is in any way possible in a capitalist society based on exploitation, profit-making and strife, it is attainable only under a consistently and thoroughly democratic republican system of government which guarantees full equality of all nations and languages, which recognises no compulsory official language, which provides the people with schools where instruction is given in all the native languages, and the constitution of which contains a fundamental law that prohibits any privileges whatsoever to any one nation and any encroachment whatsoever upon the rights of a national minority. This particularly calls for wide regional autonomy and fully democratic local self-government, with the boundaries of the self-governing and autonomous regions determined by the local inhabitants themselves on the basis of their economic and social conditions, national make-up of the population, etc.

Perekhoda selectively cites Lenin’s statement that the party “must decide the latter question [secession of a nation] exclusively on its merits in each particular case in conformity with the interests of social development as a whole and with the interests of the proletarian class struggle for socialism” to argue that he disregarded national agency, treating nations as mere instruments of a larger project. However, this interpretation is misleading and ignores the broader context.

First, the resolution itself acknowledges internal disagreements within Social Democracy, particularly attempts by the Caucasian Social Democrats, the Bund, and liquidationists to alter the party’s program. It also reflects the political climate of the time, shaped by the rise of nationalism on the eve of World War I, including Russian nationalism, which threatened working-class unity. The resolution warns that nationalist slogans were often used by landlords, clergy, and bourgeois elites — both of the dominant and oppressed nations — to deceive workers while maintaining alliances with ruling classes.

Crucially, the resolution reaffirms the party’s unconditional support for the right of oppressed nations to self-determination, including secession. Rather than denying national agency, it asserts that the party must determine its stance on secession based on broader social and class interests. Perekhoda’s interpretation distorts the meaning of the passage she cites. The resolution does not deny national agency but asserts the party’s right to determine, on a case-by-case basis, whether to support secession based on “the interests of social development as a whole and the interests of the proletarian class struggle for socialism.” It is a fundamental principle that any political party determines its own strategy — misrepresenting this as evidence of Russian imperialism is both inaccurate and ahistorical.

Furthermore, Lenin consistently advocated for national parties to be involved in internal party discussions on national questions. Writing in 1905, he emphasised:

It was strange taking part in deciding the questions raised at the conference without the participation of the national proletarian parties. For instance, the conference presented the demand for a separate Constituent Assembly for Poland... to decide this question without the Social-Democracy of Poland and Lithuania is impermissible.

This principle underscores the democratic nature of Lenin’s approach to the national question, contradicting Perekhoda’s assertion that Bolshevik policy dismissed the role of national movements.

Lenin’s position on national distinctions: A dialectical approach

Since it is impossible to prove Lenin’s imperialist inclinations, Perekhoda resorts to the “mother of all arguments” — what she calls “the ultimate telos of the Bolshevik project”. This argument boils down to a statement that whatever Lenin said was ultimately unimportant because his final objective was the fusion of all differences into a single, unified totality where all meaningful distinctions — and thus all potential for conflict — would and thus should disappear.

Perekhoda’s claim that Lenin’s vision of the eventual withering away of nations led to the erosion of Ukrainian national identity rests on a misrepresentation of Lenin’s actual strategy. While it is true that Lenin, like Marx and Engels before him, anticipated a long-term process in which national distinctions would gradually dissolve, Perekhoda’s reading ignores three crucial aspects of Lenin’s approach: the historical and dialectical nature of this process, the immediate necessity of national self-determination, and the distinction between political and cultural aspects of nationality.

Lenin did not advocate for the immediate dissolution of nations, nor did he consider national identity a mere “prejudice” that could be erased overnight. Instead, he viewed the eventual overcoming of national distinctions as an organic outcome of socialist development. Marx himself ridiculed the notion that nationalities could simply be abolished by decree. In response to Paul Lafargue’s claim that all nationalities were “antiquated prejudices,” Marx wryly observed:

The English [members of the International Council] laughed very much when I began my speech by saying that our friend Lafargue, etc., who had done away with nationalities, had spoken "French" to us, i.e., a language which nine-tenths of the audience did not understand. I also suggested that by the negation of nationalities he appeared, quite unconsciously, to understand their absorption into the model French nation.

This passage demonstrates that Marx — and by extension Lenin — understood that national distinctions could not simply be dismissed as ideological illusions. Lenin likewise insisted that the process of withering away must occur organically and without compulsion, in contrast to Perekhoda’s implication that Lenin sought to undermine national cultures.

Far from disregarding national identity, Lenin placed enormous emphasis on the right of nations to self-determination. In On the Right of Nations to Self-Determination as well as his later works, he explicitly outlined the various possible forms of national organisation, including independent states, federations and national autonomies, demonstrating a flexible and pragmatic approach to national questions. Lenin was clear that, until socialism matured enough to render national distinctions obsolete, diverse national arrangements would be necessary.

Lenin’s polemics against Stalin in 1922 further prove his commitment to national self-determination. When Stalin proposed integrating national republics into the Soviet Union as autonomies subordinated to Russia, Lenin sharply rebuked him, arguing instead for a federation of equal nations. This position was not merely theoretical — it had concrete political implications. Lenin warned that Stalin’s approach would foster Russian chauvinism and alienate non-Russian nations, a warning that history ultimately vindicated. Indeed, contemporary Russian nationalists revile Lenin precisely for his role in establishing national republics within the Soviet Union, with Putin famously calling it “a mine under the Russian statehood.”

A particularly relevant case is Lenin’s support for Ukrainian national development. In response to opposition from Russian Bolsheviks, Lenin backed Ukrainisation policies in the early Soviet period, recognising that socialist construction in Ukraine could not be successful without accommodating Ukrainian cultural and linguistic identity. These policies encouraged the promotion of Ukrainian-language education, administration and literature. Such initiatives contradict Perekhoda’s claim that Lenin disregarded national cultures.

Lenin, like Marx and Engels, distinguished between nations as political entities and nations as cultural formations. He recognised that national groups could exist and maintain their distinct cultures even without a separate nation-state. The Baluch and Kurds today, as well as the Jews at the time of Lenin’s writing, exemplify this reality. Lenin was acutely aware of cultural differences among nations and emphasised the need to account for these differences in socialist construction. This is evident in his numerous writings on national questions, where he called for active support of national development rather than forced assimilation.

Importantly, neither Lenin nor Marx viewed the withering away of nations as assimilation into dominant national cultures. The process was envisioned as one of mutual transformation, not absorption. As Marx’s quip about Lafargue’s “French” illustrates, the idea that nations should simply disappear into a hegemonic culture was alien to classical Marxism.

Perekhoda’s accusation that Lenin dismissed national identity rests on a misreading of both Lenin’s theoretical outlook and his practical policies. While Lenin foresaw a distant future where national distinctions might erode under socialism, he did not advocate for the immediate dissolution of national cultures. On the contrary, he fought for national self-determination, federalism, and cultural autonomy as necessary steps in socialist construction. His support for Ukrainisation and his opposition to Stalin’s centralising policies directly contradict Perekhoda’s claims. Lenin’s vision was not one of imperial homogenisation, but of a socialist framework that protected and nurtured national cultures while laying the groundwork for their voluntary and gradual integration into a socialist international order.

Conclusion

Having examined multiple points where Perekhoda’s analysis falls short, I would like to acknowledge where she is correct. She is right to assert that Marxists in general, and Lenin specifically, regarded communism as a universalist project. At its core, communism envisions the eventual liberation of humanity from the fetters of capitalism, enabling “the free development of each as a condition for the free development of all.” This vision inherently entails the withering away of the state and the dissolution of class distinctions, as well as the transcendence of divisions based on gender, nationality and other social constructs that constrain individual and collective freedom.

However, where Perekhoda errs is in her claim that Lenin was an enemy of diversity who tolerated it only as a temporary stage to be ultimately transcended. Both Lenin’s theoretical writings and political practice — before and after 1913 — demonstrate that he did not see class unity as antithetical to ethnic and cultural diversity. On the contrary, he viewed such diversity as an essential condition for the genuine self-determination of nations and the flourishing of socialism. His insistence on national self-determination, the right to linguistic and cultural autonomy, and the struggle against chauvinism within the workers’ movement all point to a more nuanced understanding of unity — one that does not erase difference but instead sees its recognition as a precondition for the broader liberation of the working class.

Perekhoda’s attempt to frame Lenin’s national policy as imperialist ultimately reproduces a form of refined cultural imperialism, akin to the Orientalist logic Edward Said critiqued. She rightly emphasises that socialism must respect diversity, but she simultaneously constructs the “Bolshevik project” as an Eastern aberration — an authoritarian deviation from supposedly more pluralist Western socialist traditions. Ironically, while she accuses Lenin of failing to recognise the agency of non-Russian nations, she herself selectively invokes national struggles only insofar as they support her thesis.

It is this lifelong commitment to the unity of the working class in the struggle against capitalism that makes Lenin so unpopular in modern Ukraine, and his commitment to national liberation against the dominant empire that makes him so unpopular in modern Russia. In this sense, Lenin’s vision was far from an assimilationist model in which diversity was merely a transitional inconvenience. Rather, it was a dialectical approach that recognised genuine proletarian internationalism could only be built on a foundation of respect for national and cultural differences. This is the fundamental distinction that Perekhoda overlooks, and it is where her critique of Lenin ultimately collapses.