How to think and write theoretically and critically about society

There is a growing consensus that the society we live in is not working for the vast majority.[1] It is afflicted by grinding poverty, massive inequality, endless predatory wars, life-threatening climate breakdown and so on. This society must be radically transformed. And this task of radical transformation presupposes studying society better – that is, in a scientifically rigorous and critical way. Studying society is not an easy task. Of course, it is another matter that in this world of post-truth and death of expertise (Das, 2023a), many people, especially, those inspired by teachings from “WhatsApp University”, think they have valid ideas about everything to match the ideas of intellectuals who spend years studying not only how to study but also actually studying the things they do study.

Antonio Gramsci (1971: 9) famously said that all men and women are intellectuals, even if they do not earn their living by being an intellectual. In Gramsci’s own words, all men and women can produce ideas just as “everyone at some time can fry a few eggs or sew up a tear in the jacket” (ibid.). Or, as Louis Althusser (1970: 8) said: “Everyone is not a philosopher spontaneously, but everyone may become one.” I don’t think Gramsci and Althusser would be very proud of the students of WhatsApp University and the like, who think a rigorous study of society is an “amateurish act”.[2] Studying society is difficult for many reasons, some of which I have briefly discussed in a previous article (Das, 2012b) (I will return to this in the conclusion).

The study of any aspect of society requires a scholar to, first of all, critically engage with the existing ideas about that aspect of society (including in relation to the society as a totality). This work is often called a literature review. Many younger scholars, often encouraged by their academic supervisors, resist spending much time on it. They want to jump into the field and see what is out there. It is as if one can catch a lot of fish from a sea or a river and do so safely, without making necessary prior preparations.[3] They forget that without concepts and a theory (a set of interrelated concepts) one will know nothing even if one sees and hears a lot, and that developing concepts requires hard intellectual labour.

Reviewing and representing existing ideas about the world

The very first step in the study of society is an extensive and critical review of existing literature on a topic.[4] In doing this, one addresses at least three questions:

- What does the literature say? This constitutes the review of the literature in a narrow sense. It does not include re-theorization of the topic in hand;

- What has the existing literature contributed and what are its limits?[5] This constitutes the critique part of the literature review; and,

- How must the topic of interest be (re)examined, including what new questions need to be asked and how these questions must be addressed so that one’s work will be better than the existing literature in certain respects? Here one provides an alternative theoretical framework for understanding a given topic. This is a part of the literature review in its wider sense.

These three points are elaborated below.

In terms of 1 (the review of the literature “in the narrow sense”), one needs to think about what the literature says, among other issues, about the following:

a) What the object of analysis is, and how it is different from other things (in other words, how does the existing literature conceptualize the object of analysis?);

b) Why the object of analysis[6] exists/happens/changes in time-space?;[7] and

c) What are the effects of a given object of analysis on other aspects of society?[8]

Why is a thorough familiarity with the existing literature necessary? The answer is the social character of knowledge production (Sayer, 1992) — the idea that a researcher always builds on others’ shoulders and that their work is a part of the past/current research conducted by a community of researchers. One should know what has been said about a topic so that one does not say exactly what has already been said. One also learns something from what has been said, including from scholars one may disagree with,[9] and seeks to go beyond the existing literature in certain respects. In fact, the more we know, the more we do not know. This is because the more we know, the more we come to know how to know partly by acquiring the new conceptual means of knowing. As the latter expands, we come to be aware of the areas of knowledge we might have ignored or under-stressed in the past.

One could use the three broad categories (a, b, and c above) around which to organize existing views in the literature. Or, one can keep these three broad categories in mind and invent other more specific categories around which one may discuss the literature. Often the difficulty is: how will one identify the categories around which to discuss the existing literature — i.e. how will one identify the common issues? The common issues are those that come up again and again, the issues which several scholars emphasize, if differently. In the identification of issues, one’s own tacit/implicit/semi-developed theory (or pre-existing ideas), of course, plays a role.

In doing a thorough literature review on a topic, one should read as much as one can on the topic.[10] This will allow one to identify 3-5 issues around which the existing literature can be discussed.[11]

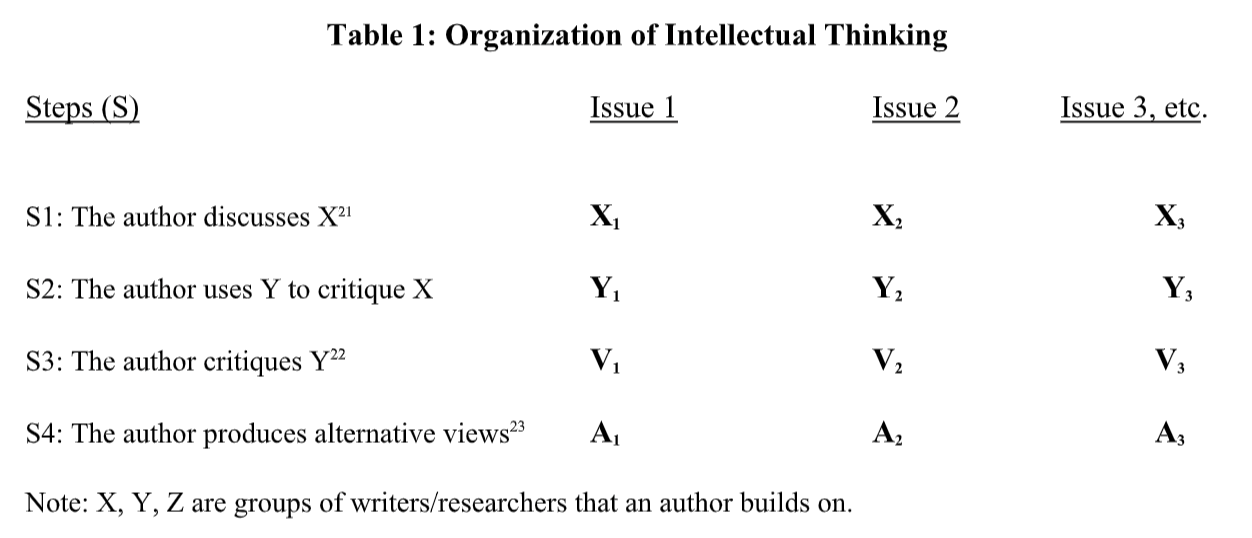

Identification/analysis of major issues covered in existing literature is one thing. Their presentation is another matter. Presenting the existing literature author-wise (author x said b, and author y said c) is, in most cases, not that interesting, although doing so is easier. An author-wise discussion often leads to repetition because five authors may say the same thing on a given topic. However, when a given issue is being discussed, one may turn to an author-wise discussion of the separate aspects of the issue. Let us say that one is writing about poverty and has identified three broad aspects of this topic or three broad issues (for example, how poverty is caused by agrarian differentiation; how it is caused by government policies, and how poverty has an impact on electoral politics). In this case, one may conduct an author-wise discussion while discussing each aspect of poverty as long as authors’ views are different from one another. Even here, one can avoid an author-wise discussion by engaging in a discussion of the sub-aspects of each main aspect. Discussing the existing literature around substantive issues signifies that one has internalized and processed the existing literature in an intellectually adequate and mature way (see Table 1).

The act/art of critique[12]

Following the review and presentation of the findings of the review begins the critique part of theoretical thinking and writing. It is important to remember that a critique — the act of finding fault (Williams, 1983: 84-85) — is always a critique of a) ideas about the world and b) the world itself. The latter exists independently of the ideas, more or less (Sayer 2000).

Being critical means being critical of the world: for example, its oppressive social relations and inequalities, and of ideas about the world, the ideas that sustain those inequalities and the ideas that do not conform to empirical evidence (Das, 2014: chapter 1). If one says the place of women is in the kitchen or that a certain religious group is inferior to another religious group and must have its rights taken away, or that people have a natural tendency to be selfish and buy/sell for profit, or that gods were born in given places and therefore their worshippers have a special right to those places, or that COVID can be shooed away by banging pots or by worshipping deities, then there is clearly something here to be critical of. The need for critique arises because these ideas are scientifically false and because these false ideas influence people’s actual behavior in a way that ultimately hurts them. One must be critical of existing ideas and of the world because one cannot assume that what exists equals what can exist. Uncritical work, as Alex Callinicos (2006) has said, equates what can exist with what does exist, and thus becomes status quo-ist. We must be critical because as Karl Marx says, what appears to be true may not be true, so we need to dig underneath the surface appearances that inadequately represent partial truth and we must be critical of ideas which reflect surface appearances.

And the art of criticism often does not know — should not know — where it takes us, and it should not be afraid of the ruling class and other powerful people, including in academia/media. In Appendix 1, I pose a list of questions which may help one to develop a critique of the existing ideas about society. That list does not, of course, exhaust all the questions one can ask of the existing literature. But using these may be a small starting point.

Critique is an important productive activity in the sphere of intellectual production. This is in two senses. Critique itself produces ideas in the form of criticisms. For example, thinking about religion critically produces the idea that religion and religion-based politics serve as an opium of the masses, the opium that now-a-days serves many right-wing political leaders (Das, 2023a). And these ideas — criticisms — in turn create a space for further production of ideas, both conceptual and empirical: that is, statements about what does not exist help one produce statements about what exists, at a theoretical and/or empirical level. Criticisms of ideas are, at least, of five types (Das, 2014): philosophical and methodological, theoretical, empirical, and practical/political.

Philosophical and methodological criticisms

Criticisms are philosophical (ontological and epistemological) and methodological (concerning, for example, the method of collection of evidence).[13] In making philosophical criticisms, one seeks to undermine the philosophical assumptions that underlie the specific substantive assertions being made in existing literature. A critic can find fault with a piece of work for being erroneous or inadequate on a number of philosophical grounds:

- idealistic/social-constructionist (reducing what exists to what is thought to exist);

- empiristic/a-theoretical (merely describing the surface reality without any statement about the underlying causal processes at the level of the wider society);[14]

- relativistic (failing to assign causal primacy to the processes including those studied);

- a-historical and a-spatial (considering what is historically specific as universal, and being blind to the fact that certain attributes of an object may exhibit spatial unevenness, respectively); and

- un-dialectical (failing to see an object in terms of its relations to other objects, to see contradictions in society and to take a systemic view about things).[15]

One can also critique a piece of work on methodological grounds, including faulty data collection methods and faulty use of statistical techniques.

Theoretical criticisms

Criticisms are theoretical (theoretical in the substantive-scientific sense and not in the philosophical sense). Here the critique, while acknowledging the contribution of the author/s, is critical of the scientific status of the concepts underlying their arguments and/or empirical observations. Theoretical criticisms, above all else, raise the issue of causality. A person says that K causes T. A critic asks: does K necessarily cause T? Why must K cause T? What is the logic of the assertion that K causes T? Is Z not a better explanation of T? Here, refuting the logic of existing work, a socialist scholar uses the power of the theory of capitalist production and exchange (for example, the content of Marx’s discussion in Capital), state theory (see Vladimir Lenin’s State and revolution), and so on.

Some people think ideas create and explain things in the world. This idea about ideas has to be inverted — twice. First: ideas reflect, more or less adequately, what is happening in the world; ideas are not primarily responsible for creating the world, although the world is influenced by ideas. In Marx’s words, “the ideal”, the realm of ideas, “is nothing else than the material world reflected by the human mind, and translated into forms of thought” (Marx, 1867:14). Secondly, because the world is class-divided, the ideas of the world reflect this fact. In particular, ideas ultimately reflect the interests of different classes and groups (more on this below). A critique of ideas is associated with — it points to — a critique of the world itself. This applies not only to science (ideas about the world) but also philosophy (of the world and ideas about it). Even philosophy is not above class interests (Das, 2017:199-208).

Empirical criticisms

Suppose an author says that Y happens in place Z. One can critique this by saying that Y happens not in place Z, but in P, and by giving evidence to this effect. Empirical criticisms are usually epistemologically weaker. These criticisms fail to challenge the very logic of a concept, that is, the validity of the general mechanisms that the concept is pointing to. Suppose an author says the state acts in the ruling class interests because ruling class people directly control the state, sitting in parliaments and controlling commissions of inquiry. In response, a critic may say that in such a case, the parliament is not dominated by people belonging to the ruling class and yet the state, more or less, serves the interest of the ruling class. Indeed, the prime minister or president of a nation can come from a modest background but champion the interests of big business.[16]

Political criticisms

Some people think that ideas about society are simply objective and without any necessary bias. This idea about ideas has to be critiqued. In a class society, while the exploiting class (ruling class) and the exploited class have their respective ideas, it is the ideas of the ruling class that tend to influence the ideas of the exploited class and create confusion in its mind:

The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of mental production [consider the media in the lap of industrialists and of political parties that are the political tools of industrialists], so that thereby, generally speaking, the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are subject to it. The ruling ideas are nothing more than the ideal expression of the dominant material relationships, the dominant material relationships grasped as ideas; hence of the relationships which make the one class the ruling one, therefore, the ideas of its dominance. The individuals composing the ruling class possess among other things consciousness, and therefore think. Insofar, therefore, as they rule as a class…they do this in its whole range, hence among other things rule also as thinkers, as producers of ideas, and regulate the production and distribution of the ideas of their age…(Marx and Engels, 1845:6)

In sum:

The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force (ibid.).

Ruling class ideas and the ideas of the exploited class co-exist. Ultimately, ideas are socialistic if they justify a social order that serves the majority (the working masses) or bourgeois if they do not (Lenin, 1902:23). In a class-divided society, maintaining neutrality with respect to a set of ideas or practices is ultimately untenable. Perhaps this is why advice is given in academia to be neutral or “well-balanced”.[17] In a society, there is a fundamental incompatibility between a) the interests of the masses in a good life and a democratic, sustainable and peaceful world without predatory wars, and b) the interests of the ruling class to generate profit and the interests of its changing governments (including those that are lesser evils) that are used to support the ruling class, alongside fattening the pockets of political leaders and officials subservient to them. Given this, the claim of many researchers to neutrality or “even-handedness” must be exposed.

Lenin’s (1905) comments on the utter impossibility of neutrality in a class divided society, where the workers, peasants and Aboriginal peoples are subjected to immense suffering, are apt:

[I]ndifference is not equivalent to neutrality, to abstention from the struggle, for in the class struggle there can be no neutrals; in capitalist society, it is impossible to “abstain” from taking part in the exchange of commodities or labour-power. And exchange inevitably gives rise to economic and then to political struggle.

Economic and political struggle is inevitable because society is exploitative, and it is exploitative in the following sense: when one exchanges one’s labour power (as a wage-earner does), one is exploited as one only gets a small part of the net product the performance of one’s labour power produces. Indeed, many do not even get a wage to buy access to the things needed to meet their basic needs. When one exchanges one’s product (as a peasant or an indigenous forest dweller does) for a price that cannot even cover the cost of production, it can lead to starvation deaths or hunger. Further, when the exploited people — the vast majority of society including some of the most vulnerable segments such as indigenous peoples, India’s ex-untouchables and Blacks — protest, the full force of the state arrives. In such an exploitative world, where avoidable hunger or illness stalk millions, neutrality is not possible:

A well-fed man is “unconcerned with”, “indifferent to”, a crust of bread; a hungry man, however, will always take a “partisan” stand on the question of a crust of bread. A person’s “unconcern and indifference” with regard to a crust of bread does not mean that he does not need bread, but that he is always sure of his bread, that be is never in want of bread and that he has firmly attached himself to the “party” of the well-fed.

There is a political implication of the above statement:

in practice, indifference to the struggle does not at all mean standing aloof from the struggle, abstaining from it, or being neutral. Indifference is tacit support of the strong, of those who rule.

Those who are “indifferent towards the autocracy” (as in pre-1917 Russia) or towards attacks on democratic rights, including of minorities (as in many countries today, including India), can be seen as tacitly supporting authoritarianism in its different forms. Similarly, in the less developed nations: “Those who are indifferent towards the idea that the struggle for liberty is of a bourgeois nature tacitly support the domination of the bourgeoisie in this struggle”.[18] In advanced nations, “those who are indifferent towards the rule of the bourgeoisie tacitly support the bourgeoisie” (ibid.).

In short: “Political unconcern is political satiety”. This is something that scholars, including in academia, often forget (Das, 2023b)

There are ideas that support the interests (and thinking) of capitalists and landlords (as well as of union bureaucrats and the “middle class people” who are deeply connected to, and materially dependent on, crumbs from the ruling classes). Then there are ideas that reflect the interests of proletarians and semi-proletarians as classes. This fact, of course, does not mean that just because an idea is in the interest of the proletarian class, it must be necessarily true in a scientific sense, that it must be immune from critique. The relation between class interest and epistemological status of knowledge claims as true or false is a difficult issue. I wish to assert without elaborating that the ruling class people distort truth to legitimize their rule. However, truth is on the side of the masses — “truth is in the interests of the people” (Mao, 1945) — and their interest is in overthrowing the system and establishing a more humane and more democratic world.

One has to be careful in making political criticisms of ideas though. On the one hand, given an intellectual assertion (for example, X causes Y), more than one political conclusion (that is, an idea about what is to be done) can sometimes be made. In other words, our view of what happens and why it happens does not entirely determine our view of what can be done at a given time and in a given place. It can only point to the necessity for a future world and to broad strategies needed to achieve it. On the other hand, in practice, reformist political conclusions can be traced to certain kinds of faulty theoretical and philosophical assertions, even if they are not recognized as faulty by their adherents.[19]

In practice, it is very difficult to separate intellectual (scientific and philosophical) criticisms from political criticisms, whether or not the latter are made. Usually, academic and media people hide their political/ normative views and claim that their knowledge-claims are politically neutral, when in fact they are not. Socialist scholars, including the few of them in academia, are often more candid about their political views. For them: class relations, and most importantly, capitalist class relations, are the most fundamental cause of the most fundamental problems of humanity and therefore the abolition of the class system through independent political mobilization of proletarians and semi-proletarians at the local, national and global scales, against the class system and its supporting political-ideological mechanisms (e.g. state; the professoriate) is the most fundamental solution to the problems of humanity (Das, 2020). One sees that one’s theory of society is at once intellectual and political.

Note that often substantive criticisms — theoretical and empirical criticisms — are the only type of criticisms that are made, but these are inevitably informed by philosophical and political criticisms, even if the connection between theoretical and empirical criticisms and philosophical and practical criticisms is not always clear. One does not criticize everything one is reading. In developing a critique, one presents a selected number of major criticisms, which may include sub-criticisms (part of a major criticism). Note also that one must try to avoid making the mistakes that one accuses one’s opponents of.

The labour of theorizing

Often scholars stop at the criticisms of existing literature and, in the light of these criticisms, may carry on their own empirical investigation.[20] A few try to offer an alternative theoretical framework, which informs one’s own empirical study. In the latter case, the framework informing their own original research is explicit. In the former case, it is implicit. Marx’s discussion in Capital I of the working day in chapter 10 or of primitive accumulation in part 8 of the book remains a great and ideal example of original research: one reads existing literature, critiques this literature, develops one’s own framework, and presents empirical material in the light of, and in support of, that framework.

One can see that doing conceptual work, including literature review in the narrow sense (in the sense of saying who has said what about a topic) is not easy. Doing conceptual work involves not only reading and thinking but also dialectically organizing one’s thinking. One way of organizing one’s theoretical thinking, including the discussion of existing literature, may be as follows: in studying a topic such as poverty, one begins by reviewing the literature on it which discusses various issues concerning the topic; one then critiques one part of the existing literature by a) using another part of the existing literature that deals with some or all of these issues and b) on the basis of one’s own interpretation of this part of the existing literature; and then builds an alternative framework which is based on the critique of existing work, the ideas in the literature one finds defensible, and one’s critical reflections on all these.

The Table above suggests that one has at least 12 bits of existing knowledge or 12 categories of existing views (4 rows and 3 columns). Conducting theoretical work like this makes it very comprehensive, critical and synthetic. An advantage of doing this is also that one cannot be accused of painting everything with the same brush because one has split the existing literature into two parts — a “thesis” and an “anti-thesis” — which lays the foundation for one’s own critical synthesis. Following this method, one produces a differentiated view of the existing knowledge, and one tries to create a new way of looking at things.

What does offering an alternative theoretical framework consist of? As indicated, it is an intellectually productive unity of opposite views. It is about finding relations among concepts in a structured, coherent manner so that one is able to provide a general understanding of how things happen in the world, that is, of how the world, or a definite part of it, works. The theory of an object says what is it caused by and/or what might it result in? Theorizing is about making statements based on observations about, for example, apples falling or companies going out of business. These statements explain each apple falling from the tree or each business failing to compete in the market, as individual examples of general mechanisms. These general mechanisms explain the behaviour not only of the particular apple or business being observed in a given time and place, but many other apples and businesses across times and places. Theorizing is about seeing the forest and not just trees, so it is an epistemologically totalizing task. In particular, theorizing, which is the most exciting part of research in my view, is about saying three things:

a. What an object is;[24]

b. What are the necessary and contingent conditions and causes for its existence;

c. What are its necessary and contingent effects of it; and

d. How conditions/causes and effects reciprocally impact each other.

The last three points must be seen together. One must ask: what is it that holds the key to understanding both the causes/conditions and effects? What is common to both the conditions/ causes and effects? One should be able to arrive at something, the examination of which will produce the answer to both b) and c), and it will reveal that conditions for or causes of an object (e.g. poverty) and its effects (e.g. illness) exist as parts of, or dimensions of, one single thing (i.e. the whole society), so causes and effects are ultimately inseparable.

Everything in the world is seen not just as a thing one can touch and feel, but as a set of relations and processes.[25] To the extent that theorizing is about seeing an object in terms of relations and about relating things to one another, it requires an understanding of the multiple relations that exist in the world.[26] In offering an alternative way of knowing an object, one produces an alternative way of a) conceptualizing the object, which is an act of drawing boundaries in one’s mind,[27] and b) then explaining the object, by using a general idea which may be applicable to the explanation of many things.[28]

How do we explain an object, O? One way is to think that certain structures of relations (S) that give rise to certain mechanisms (M1, M2, etc.) will cause O in question, assuming that the posited mechanisms outweigh the stated counter-mechanisms.[29] One’s theory of an object must ideally include all four elements: structures of relations; mechanisms (how things work) set up by the structures of relations; effects/results produced by the operation of the mechanisms; and counter-acting mechanisms that may counter the posited mechanisms that tend to outweigh the counter-mechanisms over a longer period of time and over a large and internally-integrated geographical area. For example, capitalist social relations tend to cause mechanisms of technological change, which in turn tends to cause low wages as an effect/result (assuming that counter-acting mechanisms such as government policies aimed at increasing wages are outweighed by the mechanisms posited).

A researcher who engages in empirical work on a topic on the basis of an adequate theorization, needs to also study, empirically, the contingent conditions, the conditions that are not necessary but possible and that can make a lot of difference to how the theoretically posited mechanisms work and produce effects. The contingent conditions can also be called disturbing influences:

The physicist either observes physical phenomena where they occur in their most typical form and most free from disturbing influence, or, wherever possible, he makes experiments under conditions that assure the occurrence of the phenomenon in its normality (Marx, 1867:6).

And in both theoretical and empirical work, place matters, as time does. Place and time matter not only because contingent conditions (the processes that are possible but not necessary in relation to an examination of a given object) are place-specific and time-specific. As well, in a world subjected to the universal law of uneven geographical and temporal development, studying an emerging process (a process-in-development), it is useful to study it in a place which represents or illustrates its fuller development, where possible, as long as one keeps in mind the whole world market and its internal unevenness in mind. Marx (1867:6) says this about his analysis of capitalism:

In this work I have to examine the capitalist mode of production, and the conditions of production and exchange corresponding to that mode. Up to the present time, their classic ground is England. That is the reason why England is used as the chief illustration in the development of my theoretical ideas (ibid.; italics added).

It is important to note that a time period or a place can have two entirely different, if connected, epistemological roles. Marx’s study of capitalism is not the study of capitalism of England but a study of capitalism through England. A study of poverty in Odisha or Tanzania is one thing. A study of poverty’s general traits, illustrated through a study of Odisha or Tanzania is another. Of course, in a world where everything develops unevenly, in some places an object of interest exists to a larger extent than in other places. But:

Intrinsically, it is not a question of the higher or lower degree of development of the social antagonisms that result from the [theoretically posited] natural laws of capitalist production. It is a question of these laws themselves, of these tendencies working with iron necessity towards inevitable results. The country [or region] that is more developed industrially only [tendentially] shows, to the less developed, the image of its own future. (ibid.:6-7; parenthesis and italics added)

Whether the power of the mechanisms being posited in theory is activated/counteracted is also empirical. Theory can simply say: given such and such things, X and Y will happen if no counter-mechanism operates. If indigenous people are dispossessed of their means of production (forest or farm land), they are going to have to work for a wage, other things being constant. If a person is working for a wage, they are going to be subjected to domination and exploitation in the workplace. But there is no guarantee that this will happen to a given person or a group of persons: they have to find wage-work in the first place. If the organic composition of capital rises (with machines replacing labour), the average rate of profit tends to fall over a period of time, despite the counter-mechanisms and yet in some of the years the rate of profit may rise thanks to countervailing mechanism, such as neoliberal reforms (Das, 2022:159). The fact of the matter is that producing theoretical statements about an object inside the house of theory does not mean one can just open the door and see all about that object at the door. Knowing an object requires theory and much more. But without theory, one will know very little.

In theorizing, one has to think about the entire society of which a given object of analysis (for example, climate breakdown, a fascistic threat or contract farming) is a part. The society is constituted by social relations of class (as well as other relations). These relations give rise to certain other things (mechanisms and processes). One’s object of analysis is connected to, and is rooted in, these relations and mechanisms.

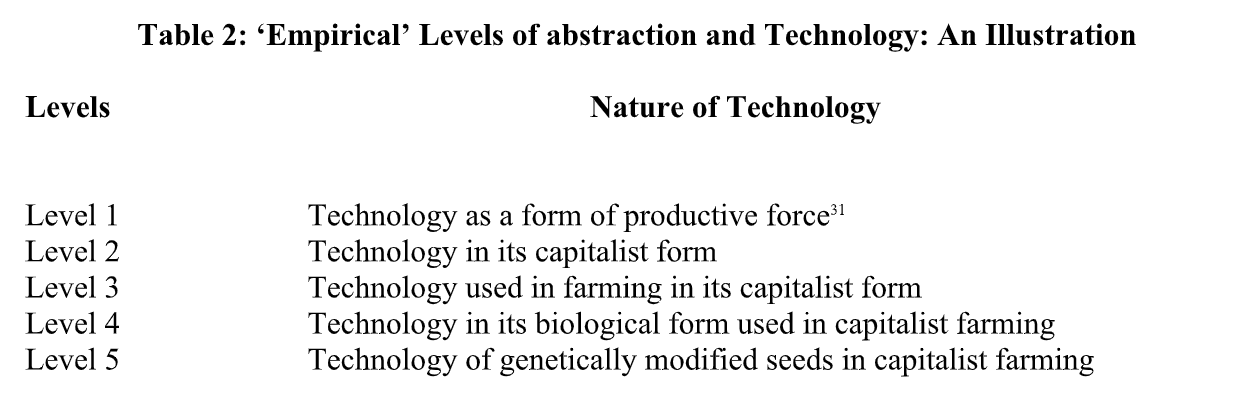

As mentioned, one begins theorizing by conceptualizing and re-conceptualizing an object in the world, whose image is reflected and actively worked upon, in our mind. An object can exist at different levels, in more or less abstract forms: an object seen at a more concrete level has more dimensions than an object seen at a more abstract level. For example, the concept of “pen” is more abstract than the concept of “broken pen”, and the concept of the “broken pen” is more abstract than the concept of “blue broken pen”. Consider technology used in production as an object of analysis in the context of farming. Table 2 shows the different levels of analysis at which technology — or for that matter any other object — can exist (or can be seen as existing), where Level 1 is more abstract and Level 5 is more concrete. Technology is seen progressively in its more concrete forms. A more concrete form of technology (for example, genetically modified seeds) represents an empirical (or near-empirical) combination of many attributes.[30]

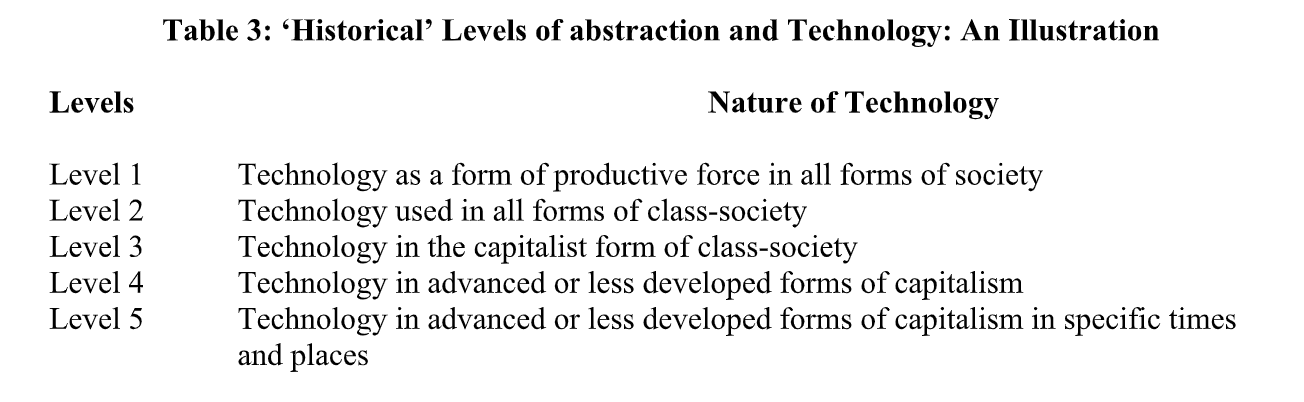

Another way of theorizing technology used in production [where a) is more abstract and e) is more concrete] would be as presented below. This, to a large extent, follows Bertell Ollman’s (2003) idea of levels of generality, which are indicative of different historical slices of human history.

As we move from Level 1 through to Level 5 above, the objective nature of technology and, therefore, the idea of technology become more and more concrete. And, if one replaces technology with any other object, the abstraction procedure will more or less hold.

In theorizing, ideally, technology has to be seen at each level in terms of its a) necessary and contingent preconditions/causes and b) necessary and contingent effects, and in terms of their reciprocal relations (relations between effects and conditions). In other words, in this example, vertically you have five levels at which technology as an object of analysis exists. Then, at each level, you have two aspects, causes/conditions and effects, dialectically connected to one another). So in total: you have “10 cells of knowledge” about one’s object of analysis.

Continuing with the example of technology, one can say that in theorizing it, one has to bear in mind the relation between what is technology and other aspects of society, within a hierarchy of abstractions. Theorizing of an object that is just a part of society (the totality) is such that the study of that object itself can say something about the totality as such. This is the beauty of theorizing. Marx (1867: 329) says:

Technology discloses man’s mode of dealing with Nature, the process of production by which he sustains his life, and thereby also lays bare the mode of formation of his social relations, and of the mental conceptions that flow from them. Every history of religion [and indeed of ideas in general]…that fails to take account of this material basis, is uncritical.

In fact, what is said about technology here can be said about a large number of topics.[32] By studying such objects as wars, academia, road transportation, and environmental damage, one can say something about the society as a whole on the basis of a proper theory of these objects.

There are many other aspects of theorizing. What is certain is that theorizing requires familiarity with philosophy, including ontological and epistemological views. One must be mindful of certain ideas about human nature too: it is important that one avoids explaining how people behave entirely or mainly in terms of trans-historical attributes of human beings.[33] And one must have a general theory of society (or social theory) which covers: relation between individual and society; how a society changes via changes in contradictory relations between its productive forces, class relations and via struggle; and relations between economic and non-economic processes, including ideas and politics, within a system in which the economic has a certain primacy. One also needs familiarity with more specific theories — theories of the most important “parts”/”aspects” of society (economy, culture, politics and environment) — such as political economy and class theory, state theory, theory of culture and meaning, and theory of the relation between society and environment/space.[34] Within each of these areas, one needs still even more specific theory, because of the stratification of the reality, that is, the idea that reality happens and exists at different levels of generality: theory of technology or theory of agrarian change as a part of the theory of political economy; or theory of state bureaucracy as a part of the state theory.

It is not possible to write an algorithm for how to theorize. However, several basic principles of theorizing can be stated (Das, 2017: 175-199). These are presented in Appendix 2. The reader may choose any given topic and think about it in the light of these principles. I have tried this many times. The list of principles boils down to the idea that adequate thinking requires these tools: “materiality” (the material foundation of society) + “sociality” (social relationships or interactions) + system (systemic nature of society, including interaction/relationships between parts) + contradiction (contradictory character of social relations). These must be an essential part of dialectical logic.

Theorizing needs practice

To develop theoretical knowledge, that is, knowledge about necessity in the world or knowledge about how the world really works, one needs to bathe in practice (both empirical work and political practice). There is an intricate relation between knowledge and practice. Marx (1845) says: “The question whether objective truth can be attributed to human thinking is not a question of theory but is a practical question”. Mao (1937) wrote that of the many types of social practice that human beings engage in, “class struggle in particular, in all its various forms, exerts a profound influence on the development of man's knowledge. In class society everyone lives as a member of a particular class, and every kind of thinking, without exception, is stamped with the brand of a class” .

It is not just that theorization, and indeed, intellectual work in general, is shaped by class struggle. It is also that intellectual work itself can be a form of class struggle, in its ideological form (Das, 2023b). Those people who engage in intellectual work that justifies and support the capitalist order (including in slightly modified forms) engage in intellectual class struggle from above; most of academia falls in this category. Those people who engage in intellectual work that opposes the capitalist order from the standpoint of the masses (workers and peasants) engage in intellectual class struggle from below.

Scholars must observe the act of production, including production of ideas (for example, how ideas are produced in universities and how this is influenced by generalized commodity production and by the propertied classes’ need for order). Then there is the issue of political practice. Among others, Marx, Engels, Lenin, Leon Trotsky and Rosa Luxemburg’s practical engagement with the world in the literary and non-literary spheres (that is, their involvement in class struggle from below) was a source of their theoretical knowledge, which in turn shaped their empirical knowledge and political strategies. Theoretical knowledge continues to evolve as new developments in the world are constantly reinterpreted and as one’s views at a point in time prove to be less effective than originally thought. It is also the case that over a period of time, one’s actual degree of practical engagement and its form will vary. Sometimes, it may take the form of the creation of ideas to help a developing movement. Just the revolutionary intent, the act of breathing and dreaming revolution, the intent which is rooted in, and in turn informs, one’s intellectual views of the world, becomes something which, when very strong, can serve as practical activity. At other times, one’s political practice may be less “speculative”. Theorizing can be, in a sense, a practical activity.

Emphasizing the importance of theory is to emphasize that spontaneous action and thought/observation is no good. Theorization allows one to go beyond the conjunctural in time-space, to go beyond the merely-empirical, beyond what is happening in the immediate surroundings. Theorization thus encourages one to think at higher scales, internationally, and over a long time period. There is suffering. There is exploitation. There is domination. But how to interpret their origin and how to understand what is to be done about them depend on theory, on conscious theoretical thinking. If one thinks that suffering can be overcome by syndicalism, parliamentarism, etc. one is guided by conjunctural thinking, spontaneous thinking, not conscious thinking. The working class’ consciousness, Lenin says, must be saturated with socialist consciousness, which requires conscious theory. No theory, no revolution. Theory is that important.

Theorizing, which involves textual exegesis, is not enough. One also needs to be familiar with empirical trends, that is, with what is going on in the world at different scales, in different areas and in different time-periods. One can and must learn about these from government and NGOs reports, social media, online radical and mainstream magazines, newspapers, blogs, tea-shops, street theatre, (alternative) cinemas, research interviews and observations, diaries, photographs, questionnaire surveys, case studies, participant observation, etc. One can and must learn from qualitative and statistical analyses of the information garnered from these. One needs to find out, for example: is inequality rising or falling here, or are farmers going out of business there. Theoretically-informed empirical study of how things are different in different places and times is a crucially important part of our understanding of the world. One’s theoretical ideas must be constantly rubbed against empirical developments that exist independently of one’s contemplation of these developments and against the ideas produced by other researchers. In the process, one may need to rethink one’s theorization, especially those aspects of theory that are more concrete.

Conclusion

We may reflect on the rich intellectual practice of Marx as a socialist thinker for a moment. He regularly read newspapers, magazines (for example, The Economist), poetry and novels. He spent an enormous amount of time reading and writing about Adam Smith, David Ricardo and Ludwig Feuerbach, among others, and took copious notes and commented on what he read. (See his long footnotes in Capital or discussion in Theories of surplus value or his review of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon). He read these scholars, appreciated what was positive in them, and developed his own criticisms of them. These criticisms, along with his more “practical work” (which included not just his political engagement in different forms but also his deep familiarity with government reports, work of history, etc.), assisted by his realistic, materialist and dialectical philosophical ideas, fed into his own alternative way of understanding the society, both at more concrete and more abstract (theoretical) levels. It should be noted that Marx (1880) even wanted to conduct a questionnaire survey. He, like Lenin, regularly made use of statistical information and created many statistical tables. Marx (1881) even made use of algebraic equations and spent time on calculus. This suggests that he was not at all opposed to using some of the methods of data collection that mainstream social scientists use (Vaillancourt, 1986: 148-158). Marx was right. He would have strongly criticized those who think Mathematics is automatically oppressive and racist.[35] A socialist and progressive thinker must make use of the positive intellectual accomplishments of humanity to make further intellectual, including, theoretical, advances.

Research has to be difficult labor. This is so because research has to be critical. It has to be critical for the reasons discussed at the outset: namely, it must uncover things which are not easily seen or felt; it has to be critical of various forms of exploitation and inequality, which are causes of many events/processes we observe. Research is difficult also because it requires the difficult work of theorization.

Theorizing is also the most exciting part of research. This is for three reasons: it helps us unpack general mechanisms in society; it informs concrete analysis of the concrete; and it points to specific political strategies to change the world. Theory is also laden with beauty. Theorizing is like telling a beautiful story to someone. In the story, there are many actors (that is, many structural processes, some of which are not even easily seen). Our audience may relate to some of them but not to others. Some members of our audience may think the story is relevant to them only partially or not at all. But, to paraphrase Marx, it is not a question of the higher or lower degree of relevance of our theory, that is, of the mechanisms that our theory talks about. It is a question of these mechanisms themselves, of these tendencies working with iron necessity towards inevitable results. The person who thinks that a given theory is less relevant to them than to another person will realize sooner or later that theory is actually telling their story too, if it is a good one.

Without good theory, the act of remaking the world in a revolutionary way is an impossible task. On many topics such as economic crisis, inequality, poverty, there is a large amount of theory.

Does the bloody capitalist/imperialist system…that thrives on racism, patriarchy, casteism, oppression of indigenous people, etc., continue because we do not have good explanatory ideas about capitalism [at a theoretical level]…The answer is: no (Das, 2021).

We do indeed know quite a bit about how the world works. Therefore, much theoretical attention — and indeed historical or historical-geographical attention — needs to be paid to why capitalism is still here. In particular, intellectual attention needs to be paid to why anti-capitalist forces are as weak and fragmented as they are (Das, 2021). Theoretical and empirical work must be conducted on this topic at local, regional and higher scales. In every single nation of the world, anti-capitalist forces are present at least at the local scale. Anti-capitalist thinkers and activists are present in favelas and slums, in Adivasi (indigenous) areas and peasant-dominated villages, in unions and environmental groups, in anti-dispossession and anti-war movements, and in the movements to defend of Blacks, low castes and religious minorities.[36]

Then there is an additional matter: while we know a lot about how capitalism works, its functioning must be re-examined from the standpoint of overthrowing capitalism. Indeed, a lot of intellectual, and theoretical, work aims to just describe and explain capitalism, while the question of revolutionary practice aimed at socialist democracy is under-stressed. This is especially true of academic work. One can read reams of paper on this or that aspect of capitalism without being able to figure out what is to be done politically about capitalism. There continues to be a need for theoretical work on capitalism, but from a different vantage point — that of the standpoint of the struggle for socialism.

“Every beginning is difficult”, Marx (1867: 6) said about the difficult nature of reading Capital I. Thinking theoretically and critically is difficult at the beginning, in the middle, and in the end! However, Marx hoped that although “There is no royal road to science”, it is the case that “those who do not dread the fatiguing climb of its steep paths have a chance of gaining its luminous summits.”[37]

Appendix 1: Why must social science be critical?

Intellectually speaking, one can become critical of existing ideas about society by asking a series of questions of a piece of work. For example:

- Does a piece of work merely describe an event/process or does it explain it as necessarily caused by specific processes?

- Does a piece of work give more powers to things/processes than they can possibly bear/have?

- Does a piece of work naturalize a phenomenon by treating it as universal when it is in fact historically and geographically specific?

- Does a piece of work stress the cultural/ideational at the expense of the material/economic?

- Does a piece of work distinguish between necessary causes/conditions from contingent causes/conditions for something to happen?

- Does a piece of work treat an event/process as a mass of contingencies or does it treat it as a manifestation/expression/effect of a more general process?

- Does a piece of work conceptualize/treat/ analyze an event/process in terms of its necessary conditions and necessary effects (which may change over time)?

- Does a piece of work stress harmony and stability at the expense of tension and contradiction?

- Does a piece of work ignore connections between things and how their connections form a system which influence the parts or does it stress the difference and disconnection between things at the expense of the connections and similarities?

- Does a piece of work stress the individual thoughts and actions as being more important than structural conditions of individual actions/thoughts?

Note: for more details, see Das (2014).

Appendix 2: Twenty guiding principles of theorization

Reader: Imagine a topic of your interest and write a paragraph on the topic by using the following principles:

- A thing (e.g. a union, crisis, technology, farming or non-farm business) is a thing and a relation between it and other things as well as a process of interaction between it and other things.

- A thing (an object of analysis) may be similar to another thing and different.

- Things undergo changes; quantitative changes can become qualitative changes.

- A thing has parts inside it which may support each other or contradict each other.

- Many things, their relationships, and the processes they are involved in constitute a structure. This can be seen as a totality.

- The totality of social relations and processes (e.g. the capitalist system; the city as a system) influences its parts, and which in turn influence the totality, the whole.

- One structure or one thing may contradict another structure, another thing.

- Ideas (consciousness, which can be true or false or contradictory) and material conditions interact within a whole in which the latter have ultimate primacy.

- There are structures and relations which set up mechanisms which, when exercised, may produce events, which may be experienced by individuals, who may react back.

- The reality exists at the level of relations/structures as well as events and experiences, including subjective and cultural experiences.

- Relations are necessary or contingent; when we theorize, necessary relations are the staple food. Always ask, is a given thing necessary for another thing?

- The concrete is not automatically accessible to us, so it needs concrete analysis: split a concrete thing into its parts, analyze the parts and put them together to create a concrete-in-thought.

- Do not be swayed or misled by what you see, what appears to be – or said to be – the case.

- Things exist at multiple levels, so abstract out and in: when focusing on how capitalism as such works, abstract out (ignore) capitalism in agriculture, for example, works.

- Think dialectically about the substantive hierarchy in abstractions: capitalism, agrarian capitalism, agrarian capitalism in mountain or aqua contexts. This is different from abstracting [in the CR mode] from X those things which are contingently connected to X.

- When studying a thing, study the forms it takes (technology, its specific forms; contract farming and its specific forms; property and its specific forms; agency, ditto). Do not treat forms/ appearances as unreal, however. A ‘thing’ is a unity of content and form.

- Then study its causes, conditions and its effects; how its effects are mediated by other things; how causes of something may be mediated by other things. Ask: for x to exist, what else must?

- Significance of the pathological: study abnormal or crisis type conditions to better understand the normal (when in a crisis, police are sent to crush workers, you understand the nature of the state).

- Use what ordinary people say as raw material in your thinking; ditto: the ideas of experts.

- Mechanisms exist at lower levels (more basic) and higher levels which have their relative autonomy. You cannot understand consciousness (a higher level mechanism) without understanding more lower level mechanisms (material conditions), but just because you understand the latter it does not mean that you understand consciousness fully.

Footnotes

[1] This article is part of a book that the author is completing titled, Capitalism, Knowledge, Class struggle and Academia. A much shorter version of this article was published in Das (2012a).

[2] On WhatsApp University (a source of fake news), often popular among right-wing people, see Bose 2023; Roy (2018).

[3] A mere intention to eat dalma (a popular dish in India’s Odisha province) or biryani (a popular dish in many parts of India) and the fact that the ingredients are available in front of us are not enough for a good dinner.

[4] This also applies to the study of nature and its interaction with society that is conducted by natural scientists, even though many of them think too that they can just go to the labs and/or to the natural environment and reveal the secrets of nature “spontaneously” (that is, without conscious theorization that requires a critical review of existing work). “Spontaneous thinking” itself does not produce new research. Nor does it produce a radically different world (Lenin, 1902:17; 23-24; 59; Das, 2017: Chapters, 10-11).

[5] See the discussion on critique below.

[6] The object of analysis could be, for example: food insecurity, child labour (in the US), labour strikes, corruption, class differentiation, state repression, portrayal of violence in movies, poverty, foreign direct investment, violence against women, Special economic zones, slums, predatory wars, etc.

[7] Of course, given the complex (multi-sided) nature of the world, one limits oneself to a selected list of causes/conditions and/or a few effects, keeping in mind that one should not separate X from Y when in the real world they are not separable. For example, to analyze poverty, one cannot separate it from the ways in which capitalism creates unemployment or a regime of low wages or governmental austerity. Of course, one cannot include all necessary conditions for an object’s existence in a piece of work because of the constraint of time. The quality of a scholarly work partly depends on the extent to which its author includes a significant number of necessary conditions for the existence of the object in question and the extent to which they avoid treating accidental/contingent conditions as if they are necessary ones.

[8] Here one focuses on, for example, the effects of poverty as an object analysis on, for example, health, rather than the effect of the concept of poverty. Poverty and the concept of poverty are not the same. The former is a real object. The latter is a thought object.

[9] Socialist and progressive scholars must consult scholarly work produced by mainstream people and organizations. There are always things in it that they can learn, especially, at a more concrete level of analysis.

[10] One should read not only the academic literature but also the literature produced by activist-scholars or scholar-activists. My personal experience has been that on a large number of topics, the work of the latter is superior to the academic work. I had not realized this in the first 15 years of my academic career, including my PhD.

[11] These 3-4 issues should be seen in terms of the three categories (a, b and c) identified above.

[12] On this see Das (2014).

[13] Often younger scholars are grilled on this by their professors: “How many people did you interview”, “How did you choose your respondents?”, “How did your positionality influence the way you asked your questions”. These are important questions, but their importance must be seen in the larger context of critique, which involves considerations that are philosophical in nature.

[14] This approach reduces the thought object to the real object.

[15] Some of these issues have been raised in Das (2012b).

[16] This is exactly the kind of criticisms that Nico Poulantzas makes in the context of state theory (see Das, 2022, chapter 2).

[17] This is a similar situation to one where a war is called unprovoked precisely because there is a need to hide the fact that it is provoked. In an interview, Chomsky (2022) indeed said this about the Ukraine war: “it's quite interesting that in American discourse, it is almost obligatory to refer to the invasion as the 'unprovoked invasion of Ukraine'. Look it up on Google, you will find hundreds of thousands of hits. Of course, it was provoked. Otherwise, they wouldn't refer to it all the time as an unprovoked invasion. By now, censorship in the United States has reached such a level beyond anything in my lifetime”.

[18] The majority of socialists in less developed nations believe that all that is possible there is a democratic revolution, one that protects the interests of the so-called national sections of the capitalist class, although the revolution is to be led by the proletarians.

[19] For example: those who rubbish the labour theory of value, or the tendency of the average rate of profit to fall due to rising organic composition of capital, or who think about class as merely income inequality or as a matter of attitude or some kind of social construction, tend to be (social-democratic) reformists. Those who explain the economic world in terms of human nature, utility, and consumer preferences tend to be those who wish to see capitalism go on forever. Denying the objectivity of relations in the world, relations that are independent of individual actors’ will, and producing explanations of the world in line with that denial, which is so common now, is very closely associated with ideas that reproduce the existing system. Leave materialism. Enter reformism. Almost. Similarly, when one leaves dialectical thinking, the result is also the same (see Das, 2017, chapter 5).

[20] Lenin’s Development of Capitalism is almost an example of this. This is in the sense that following his discussion and criticisms of Narodniks he goes on to empirically show how class differentiation is happening and corvee type relations are being undermined gradually. Of course, this does not mean that Lenin did not have a theory in mind but that this theory remained implicit or semi-developed and under-articulated. In the course of presenting his empirical discussions and in the conclusions to different chapters, Lenin indeed makes a series of conceptual points whose intellectual power, as far as class theory in the context of the countryside is concerned, remains unparalleled.

[21] Here one says what a group of writers is saying about the different aspects of a given topic represented as issue 1, 2, 3, etc.

[22] An author begins with the ideas of a given set of writers (X group). The author then critiques the X group by using the ideas from the Y group. The author then critiques the Y group to develop their own framework which is based on their critique of the Y group and which also builds on the ideas of others (the Z group).

[23] This is based on the author’s critical assessment of the existing work and builds on the work with which the author agrees.

[24] Here one re-conceptualizes an object; one asks: what does the scope of thought object (the concept) which refers to a real object cover? And one changes the boundary/scope of the concept depending on the situation at hand; this is what reconceptualization is about.

[25] A village must be seen in terms of a) the relations among things and processes inside the village, b) the relations between a given village and other villages and to cities that are near the village and those that are farther away.

[26] Relations in the world are substantive and formal relations, and necessary and contingent relations. There are also relations of similarity and relations of difference, and relations are of contradiction and harmony, and so on (Das, 2017: Ch 5).

[27] In drawing boundaries around observed/observable objects to create concepts, one answers the question of what does X mean, and how is it different from other objects?

[28] Note here that the concept, what it refers to, and the word which is used to refer to the concept are different.

[29] This is based on critical realist philosophy as popularized by Andrew Collier, Andrew Sayer and others.

[30] Empirical in the sense that the attributes of an object seen at a more concrete level are not necessarily connected. A technology does not have to have these attributes — biological and genetic modification. In the concept of the blue broken pen, being broken and being blue are not necessarily related. This shows why/how a purely empirical method of abstraction is not very useful.

[31] These two levels can be combined into one.

[32] Marx says that understanding technology helps one understand social relations. Seen in a less determinist way, this is an interesting observation. On the class character of technology see Das (2012c).

[33] On human nature see: Sayers (2005); for a critique of Sayers, see Byron (2014).

[34] See Plekhanov’s Fundamental problems of Marxism as well as Marx’s famous Preface to a contribution to the critique of political economy.

[35] “Reality has a qualitative dimension as well as a quantitative dimension. Facts of economic development, rainfall, climate change, frequency of imperialist wars, and so on can all be measured and analyzed, and Mathematics as a universal language of humanity plays a useful role here. Because state-sponsored racism has utilized mathematical numbers, Mathematics itself is seen as inherently racist, so there is a push for ethnomathematics, i.e., Mathematics for, and of, the people of color (Costa and Hanover, 2019). So, the disregard for facts becomes a disregard for Mathematics” (Das, 2023:85).

[36] It is important to study anti-capitalist thinkers and activists’ accomplishments and failures, both theoretical and practical, without the negativism that characterizes some socialists who tend to be nearly as critical of fellow socialists as of the capitalist system.

[37] The certainty of the joy of theoretical thinking which produces an ‘artistic whole’ and the inevitability of the ‘fatiguing climb’ are two sides of a dialectical whole.

References

Althusser, L. 1970. ‘Philosophy as a Revolutionary Weapon’. New Left Review, Issue. No. 64. Available at: https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/althusser/1968/philosophy-as-weapon.htm

Bose, R. 2023. ‘The Age Of WhatsApp University And A Political Animal Called Cow’, Outlook. https://www.outlookindia.com/national/the-age-of-whatsapp-university-and-a-political-animal-called-cow-magazine-256751

Byron, C. 2014. A critique of Sean Sayers’ Marxian theory of human nature. Science & Society, 78(2), 241–248.

Callinicos, A. (2006). The resources of critique. Cambridge: Polity.

Chomsky, N. 2012. 'Not a Justification but a Provocation': Chomsky on the Root Causes of the Russia-Ukraine War. Interviewed by R. Baroud, R. https://www.commondreams.org/views/2022/06/25/not-justification-provocation-chomsky-root-causes-russia-ukraine-war

Das, R. 2012a. Thinking/writing theoretically about society. Radical Notes. Available at: https://radicalnotes.org/2012/12/25/thinkingwriting-theoretically-about-society/

Das, R. 2012b. ‘Why must social science be critical and why must doing social science be difficult?’. Available at: https://radicalnotes.org/2012/11/03/why-must-social-science-be-critical-and-why-must-doing-social-science-be-difficult/

Das, R. 2012c. ‘The Green Revolution and Poverty: A Theoretical and Empirical Examination of the Relation Between Technology and Society’, Geoforum, 33:1, 55-72

Das, R. 2014. A Contribution to the Critique of Contemporary Capitalism: Theoretical and International Perspectives, New York: Nova Science Publishers

Das, R. 2017. Marxist class theory for a skeptical world. Leiden: Brill

Das, R. J. 2020. On the Urgent Need to Re-Engage Classical Marxism. Critical Sociology, 46:7–8), 965–985. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920520948930

Das, R. 2021. The weapon of criticism cannot replace the criticism of the weapon: What knowledge do we need for revolution against capitalism. Available at: https://links.org.au/weapon-criticism-cannot-replace-criticism-weapon-what-knowledge-do-we-need-revolution-against

Das, R. 2022. Marx’s Capital, Capitalism and limits to the state: Theoretical considerations. London: Routledge.

Das, R. 2023a. Contradictions of capitalist society and culture: The dialectics of love and lying. Leiden: Brill.

Das, R. 2023b. Capitalism, Class Struggle and/in Academia. Critical Sociology, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/08969205231152560

Gramsci, A. 1971. Selections from prison notebooks. Ed by Q Hoare and G. Smit.. New York: International publishers.

Lenin, V. 1902. What is to be done? https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/download/what-itd.pdf

Lenin, V. 1905. The Socialist Party and Non-Party Revolutionism https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1905/dec/02.htm

Mao, T. 1945. On Coalition Government. Marxists.org. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-3/mswv3_25.htm

Mao, T. 1937. On practice: On the Relation Between Knowledge and Practice,

Mao, T. Between Knowing and Doing

https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-1/mswv1_16.htm

Marx, K. 1845. Theses on Feuerbach. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/theses/theses.htm

Marx, K. 1880. A Workers' Inquiry. Available at: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1880/04/20.htm

Marx, K. 1881. Marx's Mathematical Manuscripts https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1881/mathematical-manuscripts/

Marx, K. and Engels, F. 1945. German ideology. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/Marx_The_German_Ideology.pdf

Ollman, B. 2003. Dance of the dialectic. Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

Roy, S. 2018. ‘WhatsApp — India's leading university’. The Hindu (July 7)

Sayer, A. 1992. Method in Social Science: a realist approach. London: Routledge

Sayer, A. 2000. Realism and social science. London: Sage.

Sayers, S. 2005. Why Work? Marx and Human Nature. Science & Society, 69:4, 606-616

Vaillancourt, P. 1986. When Marxists do research. Westport (Connecticut): Greenwood press.

Williams, R. 1983. Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. New York. Oxford University press.