Kautsky, Lenin, Stalin and revolutionary Russia

Reposted from International Viewpoint , August 13, 2022

Stalin: Passage to Revolution,

By Ronald Grigor Suny.

Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020.

857 pages. $39.95 hard cover

Revolutionary Social Democracy: Working-Class Politics Across the Russian Empire (1882-1917)

By Eric Blanc.

Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2022.

455 pages. $36.00 paperback

Karl Marx once commented: “Philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.” Less mature activists prefer the posture of changing the world over the hard work of understanding it, but as the young Marx also thundered: “Ignorance never did any one any good!”

Inseparable from any serious commitment to changing the world for the better is an understanding – an “interpretation” – of the world. Particularly useful to revolutionary activists are disciplined and informative interpretations of previous efforts to change the world. The Russian Revolution of 1917 has, therefore, long been a focal-point for revolutionary activists. Two cutting-edge interpretations from US Marxist scholars – Ronald Suny and Eric Blanc – have recently appeared, providing important insights for scholars and activists alike.

Marxism’s golden age

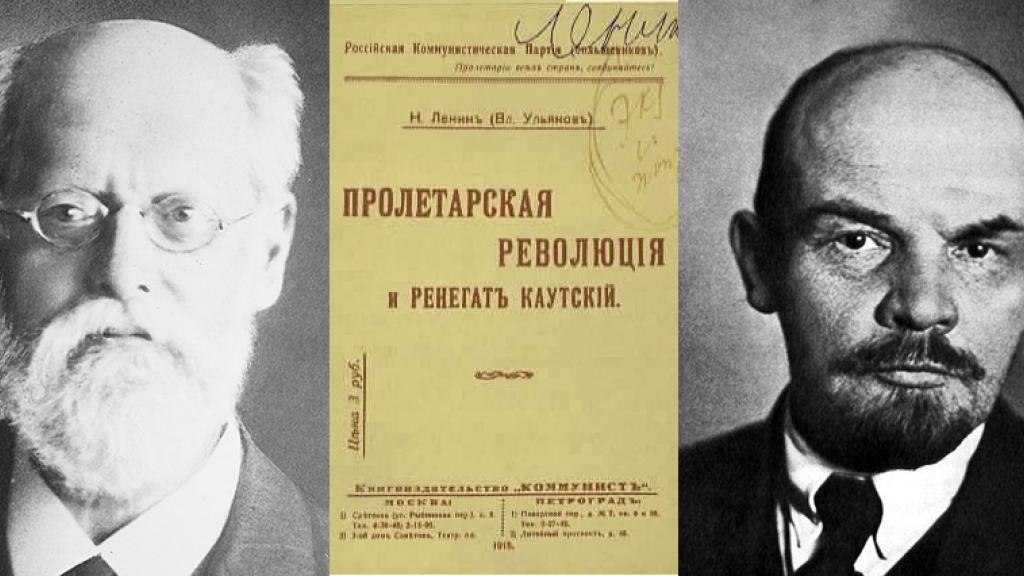

Marxism’s political terrain has commonly been described by emphasizing a three-way split: revolutionary Marxism (represented by the likes of Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, and Rosa Luxemburg); Social-Democratic reformism (often associated with Karl Kautsky and Eduard Bernstein); and authoritarian Stalinism. But Suny and Blanc start us off in the “golden age” before things separated out that way.

Back then, “Social-Democracy” was synonymous with working-class socialism, whose founding document was provided by Marx and Engels in the Communist Manifesto, updated by the Erfurt Program of the massive Social-Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). Within the SPD and in other affiliates of the Socialist International (Second International), there were certainly elements pulling away from the revolutionary orientation associated with Marx. But they had to come up against the strictures of the SPD’s influential theorist, Karl Kautsky, who was an inspiration to such revolutionaries as Rosa Luxemburg and V.I. Lenin. As for “Stalinism,” it did not exist – Stalin happened to be a fairly capable practical organizer aligned with Lenin in the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party, very much in the revolutionary wing of the movement.

Neither Suny nor Blanc claims to provide a finished product. In each case, we are offered important and insightful contributions to a larger collective process of understanding, and they must be approached critically to make the best use of what they provide.

Two authors

Ronald Suny has over five decades of experience as a teacher and scholar. He has helped shape and reshape the study of Russian revolutionary movements and the complex, contradictory Soviet experience with an accumulation of rich essays recently published by Verso – Red Flag Unfurled: History, Historians, and the Russian Revolution (2017) and Red Flag Wounded: Stalinism and the Fate of the Soviet Experiment (2020). These are “must-read” works for anyone interested in the field of Russian and Soviet history, and in the history of Marxism and Communism. Suny has also written a pathbreaking account The Baku Commune, 1917-1918 (1972) and an outstanding textbook The Soviet Experiment: Russia, the USSR, and the Successor States (1998). All this and more.

Eric Blanc is an up-and-coming historical sociologist, with one previous book to his name, Red State Revolt: The Teachers’ Strike Wave and Working-Class Politics (Verso 2019). Unlike Suny, most of Blanc’s life (so far) has been associated not with academe but with left-wing activism.

Blanc was once a youthful leader of a small group adhering to the interpretation of Leninist-Trotskyist perspectives, associated with an international current whose best-known leader was Pierre Lambert. He moved on from that into a broader, more politically diverse entity, the International Socialist Organization. After that group’s implosion, he joined with some of its members in an effort to create a cohesive left-oriented Bread and Roses caucus in the massive, amorphous Democratic Socialists of America, with an inclination to work in the “progressive” wing of the Democratic Party. He is also associated with the mass circulation left-wing magazine, Jacobin. (Interestingly, Suny wrote a positive review of Blanc’s book in Jacobin’s online component.) Blanc’s trajectory (of which I am critical) has been to challenge the revolutionary perspectives of Luxemburg, Lenin, and Trotsky, in preference to those of Karl Kautsky. Some see Blanc’s approach as expanding and deepening socialism’s popular influence. Others see him as a “renegade” whose studies are to be denounced even by those who can’t be bothered to read his book.

Revolutionary Social Democracy

Blanc’s achievement must first be acknowledged. Employing linguistic skills in eight languages, he delves both into the ocean of secondary literature, but also into multiple archives in his search for what happened in the empire of tsarist Russia – that “prison-house of nations” – between 1882 and 1917, culminating in the Russian Revolution. His focus is on the working-class and the labor movement, but he understands that what happened in “the borderland” regions outside of Russia proper is an essential part of the story. This contrasts with the way the story is commonly told, and the result is a wealth of invaluable material.

Page after page provides explosions of information, insights and ideas presented with such energy as would come from release of a tightly coiled spring. Sociological modeling connects a variety of informational dots into sweeping generalizations meant to advance our understanding. Patterns emerge that seem to challenge commonly held assumptions about what happened in history. Anyone who cares about such things cannot afford to ignore this incredible book.

It will be impossible, in the space of this relatively short review, to cover all positive qualities in this fertile volume. Half a dozen examples will have to suffice.

1. On Bolshevik organizational norms. Often attributed to Lenin’s genius (whether benevolent or malevolent) in creating “a party of a new type,” these norms were hardly monopolized by the Bolsheviks – they were common among revolutionaries of various organizations throughout the Russian Empire. They existed to facilitate survival from authoritarian repression, though Blanc indicates that, at the same time, they helped to nurture a political culture which was not afflicted by the bureaucratization and reformist impulses that came to permeate German Social Democracy.

What has commonly been tagged as organizational “Leninism” is sometimes summed up as a “top-down conspiratorial organization” (p. 122), or an “efficient, centralized, disciplined underground apparatus” (p. 100), or as “tight discipline, centralized leadership, professional revolutionaries, and the use of a newspaper as a collective organizer” (p. 88). Blanc shows that such norms were utilized by the Mensheviks and various non-Bolshevik political currents in the borderlands. He explains that “conditions of Russian absolutism obliged Marxists of all nationalities to adopt a different approach from their counterparts in Western Europe” (p. 13). There was a strong counter-trend, particularly over time, for revolutionaries (including Lenin) to nourish democratic organizational functioning even in Tsarist Russia.

For Lenin and all the others, “a sharp distinction was made between countries with and without political freedom.” Blanc elaborates: “In countries with civil liberties and parliaments, revolutionary Marxists argued that social democratic parties should focus on patient and peaceful activities such as promoting socialist ideas through the press, building strong party organizations, running in elections to further spread the message, and building trade unions” (p. 55).

One additional point that Blanc usefully emphasizes and explores in his chapter on “Working Class Unity” is the problem of what he calls “monopolism” – the belief on the part of a revolutionary group that it must dominate the political terrain within the working class. This led to a profound sectarianism afflicting the Bolsheviks but also, as Blanc shows, most of the currents in the early Social Democracy in Russia and other parts of Europe. This was reflected in a refusal to work with other groups on the left, and also in an insistence that trade unions and other “mass non-party organizations” (even the early workers’ councils, the soviets) must embrace the program of the revolutionary party.

Blanc shows that this sectarian sterility was profoundly challenged and altered by the realities of the 1905 revolutionary upsurge, and that “the years following 1905 were marked by a nearly universal Marxist acceptance and implementation of united front tactics” (p. 221). He comments that in this learning period “Marxists still had no vocabulary or articulated strategy for collaboration between radical currents inside the workers’ movement” (p. 223), and that “the strategy of the united front was not formally articulated until after 1917,” although by then “its associated practices had by this time already become the norm across Russia” (p. 221). Indeed, as John Riddell has shown in his massive documentary volumes, this became a central focus in the early years of the Communist International.

One key aspect of this was the increasingly accepted understanding that socialists should not insist that trade unions be formally controlled by the revolutionary organization. Rather, in helping to build unions, they should concern themselves with “the political spirit that guides the trade unions.” This spirit that Marxists should advance involved “a class struggle orientation, against an insular, narrow-minded trade unionism orientated towards limited sectoral demands and class collaboration with the employers” (p. 213). Their consistency in initiating and building non-party unions, while pressing for this orientation, enabled the Bolsheviks and other revolutionaries to become a powerful force within the trade union movement in the insurgent years of 1912-1914, and in 1917.

2. On “playing dirty.” Many anti-Leninists on the left, as well as liberal anti-Communist scholars, have pointed to purported examples of repressive, sectarian and manipulative behavior on the part of Lenin, asserting that these are distinguishing characteristics essential to the Leninism of Lenin. Even to the extent that Lenin is guilty as charged (and Blanc indicates that sometimes Lenin was not guilty), Revolutionary Social Democracy points to multiple examples of such behavior on the part of activists across the left spectrum, including among critics of Lenin who sport very “clean” reputations. To the extent that Bolsheviks and other revolutionaries distinguished themselves, it came from doing better than that.

3. On relations between workers and intellectuals. A long-standing myth has been that Lenin insisted workers don’t have the capacity, on their own, to develop socialist consciousness, that they need the tutelage of non-worker intellectuals to tell them what to think and what to do. Blanc demonstrates that this is absolutely false, that questions of the role of intellectuals and relations between intellectuals was complex and wrestled with throughout the revolutionary movement, but that elitist assumptions were alien to Russian Marxists, Lenin included. There is more to be said on these matters – and Blanc very capably says more in an illuminating and helpful chapter.

4. On “the national question”. All Iskra supporters of 1903 (whether they became Bolsheviks or Mensheviks) shared in rejecting the Jewish Labor Bund’s insistence that, while affiliating with the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP), it be allowed to exist as a separate organization to organize Jewish workers. To deny the right and need for specially oppressed groups to organize and struggle against the oppression could be seen as short-sighted and perhaps reflecting the biases or blind-spots of those from the “oppressor group.” What Blanc points out is that not only did the Bund prove itself in later years to be effective in what it set out to do, but that this was finally recognized by Bolsheviks and Mensheviks alike – who ended up accepting what they had so fiercely resisted in 1903.

5. On Karl Kautsky. Following the recent line of argument advanced by Lars Lih, we are treated by Blanc to a superb and nuanced discussion of Kautsky, “the most influential exponent” of what Blanc consistently terms “orthodox Marxism.” He was the most widely read Marxist in Europe whose credibility and authority were unsurpassed in Russia and its borderlands. “But the empire’s socialists by no means considered themselves to be ‘Kautskyists,’” Blanc notes. “Rather they viewed Kautsky as the foremost defender of revolutionary social democracy, a tradition established by Marx and Engels and articulated by a range of subsequent socialists across Europe.” It has become commonplace to dismiss Kautsky’s Marxism as “mechanical” and “wooden” and lacking in critical-minded and creative qualities – when compared with Luxemburg and Lenin – but Blanc provides a consistent defense (pp. 36, 38-39, 50, 51, 54), as such comrades as Lenin surely would have done as well, at least until 1914.

While he sees Kautsky as the foremost proponent of revolutionary Marxist theory up through 1909, however, Blanc also recognizes that “Kautsky himself made a turn to the right after 1909, eventually bending to the SPD bureaucracy and reversing many of his former positions.” It is wrong to blame Kautsky’s version of Marxism for the Social Democratic Party’s “abandonment of revolutionary politics, culminating in its support of World War One and its thwarting of the German Revolution” (p. 39). The explanation actually runs in the opposite direction.

When Kautsky’s theorizations were welcomed by the SPD leadership under its “grand old man” August Bebel (a leadership to which Kautsky was always inclined to defer), theory and practice seemed well aligned. But as the aging Bebel gave way to the younger leadership team which he had nurtured, Kautsky’s authority evaporated. Blanc explains that “the German party’s leadership, from at least 1906 onwards, was not comprised of ‘Kautskyists’, but rather of a strata of full-time functionaries who were dismissive of socialist theory in general and Kautsky’s writings in particular.” In order to maintain a modicum of influence and “relevance,” Kautsky tacked rightward. Blanc’s elaboration is revealing (p. 40):

The German SPD bureaucracy’s risk aversion combined with its distinct structural interests as a caste of functionaries, facilitated an unconscious adaptation to the bourgeois polity. In periods of relative social stability, the labor officialdom could balance its political moderation with ongoing support for class struggle within controlled parameters. But when the German ruling class required that the organized workers’ movement support the war in 1914 and prop up the regime in 1918-1919, top party and union leaders were unwilling to risk the consequences of opposition.

Lenin’s Bolsheviks may not have represented “a party of a new type,” but they represented a party that in fact was of a qualitatively different type than the SPD. Revolutionary Marxist theory was not disconnected from the practical leadership, and from the practical policy perspectives of the RSDLP, as was the case within the SPD. Although Blanc doesn’t emphasize this, Lenin was a leader of the Bolsheviks in a way that Kautsky would never be a leader of the SPD. Even though Lenin – as all Russian Marxists – was profoundly influenced by Kautsky, Lenin’s Marxism was different from Kautsky’s “orthodoxy” because his connection with revolutionary practice was different: reflecting his very different kind of connection with a very different kind of political party in a very different context of struggle.

6. On the nature of Russia’s 1917 revolution. Far from being the elitist coup d’etat as portrayed by anti-Communists, the October 1917 revolution was viewed by those who made it, and by the many millions who supported it throughout the Russian empire, as the defense and consummation of the radical-democratic aspirations of February’s revolutionary overthrow of the Tsar.

Russia’s masses “did not view the February Revolution as marking the onset of liberal capitalism.” On the other hand, as one Bolshevik later explained, in calling for “all power to the soviets” (that is, power to the democratic councils of workers and soldiers) “we did not think yet about moving immediately to socialism.” The point was that, in order to realize the aspirations of the masses who overthrew the Tsar, “it was necessary to … break from the bourgeoisie.” From late April through October “the Bolsheviks churned out leaflet after leaflet, reaffirming the same simple message: to satisfy the demands of the people, workers and their allies must break with capital and take all power into their hands.”

Taking a radical democracy as far as it could go, the Bolsheviks insisted, would not only enable workers and peasant to secure peace, bread, land, and liberty, but would also “unleash the international overthrow of capitalism” (pp. 373, 376, 379, 383, 387). Unfortunately, Blanc minimizes into non-existence a debate among Bolsheviks around Lenin’s April Theses, a matter I have discussed elsewhere in a friendly polemic. But that is secondary to the key point he emphasizes.

Problematic qualities

Blanc interweaves past and present. “A critical engagement with the past remains an indispensable instrument for critically confronting the present,” he announces on the first page. “The experience of socialists across the Russian Empire,” he writes in his conclusion, “should push us to rethink how workers’ movements and revolutionary processes developed in the past – and it may even help organizers more effectively challenge capitalism in the future” (pp. 1, 408).

But critical questions have been raised. Does the author structure the story of what happened in history in order to promote a particular strategic or tactical orientation in the here-and-now? Is he settling accounts with what he now sees as a “sectarian” past? Is he looking to justify “opportunistic” innovations?

Setting all that aside, it is often the case that one’s greatest strength can also be related to one’s greatest weakness. Sweeping generalizations sometimes become superficial overgeneralizations, with patterns which seem to be persuasively traced evaporating on closer inspection. Given the remarkable scope of this study, such questions inevitably arise. Nor does the book’s three-page index facilitate a critical-minded wrestling with such questions.

A very important assertion can be made with reference, in a footnote, to one or another secondary source, then backed up with a quote from a document found in the archives. But perhaps the assertion is false or one-sided or misleading – how can we know without checking the source itself, and perhaps weighing it against other secondary sources that assert the contrary? A back-up quote from the archives may help to restate the assertion but does not by itself prove its truth.

Whatever the reasons, there are problematic points, sometimes outright contradictions, in some of what Blanc has to say. Here I want to restrict myself to four specifics.

First, there is consistent reference to something Blanc calls “orthodox Marxism.” The linkage of the two words is not uncommon, yet the meaning seems problematic. Orthodoxy can mean: a body of righteous/correct opinion; a common and “normal” approach; a set of dogmas. This seems inconsistent with the qualities of the Marxism adhered to by Marx himself and by such people as Lenin – who stressed such things as: rejection of dogma; fluidity; contradictory qualities; critical-mindedness; “guide to action.” A Polish Marxist quoted by Blanc, Julian Marchelwski, insisted that “Marxism is not a ‘template’ but ‘a tool for creative work’” (p. 54). What Blanc actually means by orthodox Marxism is not clearly specified. At one point he terms it as a position “closest to the stance of Karl Kautsky” (p. 64), and at another as simply synonymous with Marxism itself (p. 67). The term is used often, without clear and consistent definition.

Lack of theoretical clarity arises in a second troubling feature in Revolutionary Social Democracy. One is tempted to say that if this book has a villain, that person is Rosa Luxemburg. Almost every time she is mentioned, it is a negative reference, presenting her as a sectarian and authoritarian. Generally this has to do not with the German Social Democratic Party but with her other organization, the relatively small Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKiPL). Providing less a systematic analysis than a collection of pot-shots, Blanc refers us to his article on Luxemburg in the journal Historical Materialism for “a full discussion of these questions.” Yet that Poland-focused article is hardly a full discussion, admitting that “a comprehensive assessment of Luxemburg’s politics … is beyond the scope of this paper.”[1]

The way Blanc handles the Bolshevik-Menshevik split is the third example. The Bolshevik and Menshevik factions, as Blanc points out, emerged from explosive debates at the 1903 second congress of the RSDLP. The two issues: (1) how should a member of the RSDLP be defined (Lenin lost this and accepted the defeat), and (2) Lenin’s proposal that the editorial board of the RSDLP paper Iskra be reduced from six to three (Lenin won this, but those who were becoming Mensheviks refused to accept defeat). Blanc tells us that “each faction rapidly produced a plethora of heated polemics, the hyperbolic content of which has led subsequent scholars and socialists to grossly exaggerate the underlying issues in dispute” (p. 264).

Blanc follows up on this by discussing the polemics. The Mensheviks, he observes, “concentrated on demagogic attacks against Lenin, who they claimed was a power-hungry dictator.” We have already seen that Blanc dismisses this attack as distorting the realities. But then, in an apparent show of evenhandedness, he asserts: “Lenin and other Bolsheviks unconvincingly argued that their hitherto close comrades virtually overnight had succumbed to opportunism” (p. 264).

In point of fact, Lenin’s initial response to the split was different from this. He argued (in various letters and in One Step Forward, Two Steps Back) that he was not a power-hungry dictator, that the Mensheviks were being unreasonable while he was being democratic, and that there seemed no good political basis for the existence of two factions. This changed later in 1904, when the Menshevik-controlled Iskra called for a campaign for democratic rights to be waged under the leadership of pro-capitalist liberals. The author of this “line article” was Pavel Axelrod. Lenin’s problem with it was hardly an “overnight” discovery.

Elsewhere in the book, Blanc notes that “both Axelrod and Plekhanov argued at various times that workers should be prepared to self-limit their struggle so as to not frighten off the liberals from joint action against Tsarism,” and that “both Lenin and Martov were critical of Axelrod’s stance on liberalism, which in their view overestimated its progressiveness and vitality” (p. 174). But now Martov was embracing the conception of a worker-capitalist alliance in the struggle for Russia’s democratic revolution. This was in stark contrast to the more radical demand of Lenin’s Bolsheviks for a worker-peasant alliance. Blanc inaccurately claims this difference emerged after the December defeat of the 1905 revolutionary upsurge – but it actually emerged in 1904, and it was central to Lenin’s polemic Two Tactics of Social Democracy in the Democratic Revolution in the spring of 1905.

A fourth set of problematic contradictions revolves around an insertion into the narrative of what could be tagged “The Great Finnish Counter-Example”. Here Blanc departs from the broad understanding of “revolutionary social democracy” that characterizes most of his narrative. It narrows down to a very specific orientation, theoretically propounded by Kautsky, very much distinguished from the orientations of such people as Lenin, Luxemburg, and Trotsky. It is injected into current debates about strategic orientations for socialists today. “Finland’s revolution stands out as one of the exceptional instances of workers seizing power under a parliamentary regime,” he asserts. It vindicates “efforts to push toward revolutionary transformation by expanding republican democracy. As such, socialists today would do well to reclaim radical republicanism” (pp. 314-315).

The Finnish Social Democratic Party was different from its German counterpart because it was not dominated by an opportunistic bureaucracy, Blanc tells us, and it was unlike Social Democrats in the rest of the Russian Empire because it functioned in a political context characterized by a vibrant parliamentary system and democratic freedoms. “The Finnish SPD leaders sought to implement Kautsky’s old vision of patiently accumulating forces for the final revolutionary blow,” he asserts. “As such, their politics and practices in 1917-18 pose a serious challenge to those who dismiss that anti-capitalist potential of revolutionary social democracy” (p. 140).

Blanc interweaves the Finnish counter-example with a critique of Lenin’s 1917 classic The State and Revolution. His discussion of what Lenin has to say is not systematic, but his defense of Kautsky against Lenin’s critical commentary certainly is. Blanc prefers Kautsky, whose orientation, he feels, provided valuable guidance to the Finnish comrades. “The SDP seized the available openings to raise class consciousness via popular associations and sustained electoral work, culminating in its 1916 parliamentary victory,” he writes. “The strength of its organizing and the legitimacy granted by its electoral majority, gave the party sufficient leverage to face-off with Finland’s powerful and well-organized bourgeoisie” (p. 140). When Finland’s ruling class then moved, in 1917, to dissolve the socialist-dominated parliament, a revolutionary situation arose. Blanc acknowledges that the Finnish Social Democratic leadership then fumbled badly and lost big, but he believes this was not inevitable and does not invalidate the Finnish counter-example. “One can criticize this or that tactical decision of SDP leftists,” he concludes, “but the big story of Finland in 1917-18 is that the actions of orthodox Marxists demonstrated the ruptural potential of revolutionary social democracy” (p. 313).

Whatever one makes of the Finnish counter-example, Blanc presents it in a way that is inconsistent with much that is valuable in Revolutionary Social Democracy.

Key flaw

The key flaw in Revolutionary Social Democracy is highlighted at the start of the book’s final chapter. “Leninism was founded on two interrelated myths about 1917,” Blanc tells us. “To challenge these twin myths, this chapter will show” that the myths were far from reality (p. 343). Before identifying the myths, let’s consider the methodology. Three things are noteworthy. First, the term Leninism is as abstract, slippery, and ill-defined in this book as the term orthodox Marxism. Second, we are treated to a sweeping generalization regarding a complex matter. Third, Blanc’s book is concerned with making a case – that today’s activists should embrace “orthodox Marxism” (represented by Kautsky) and reject “Leninism” (the orientation of Lenin).

In my imagination, I picture the following scenario. As Blanc was researching and composing his book, something happened. He concluded that the “Leninist” orientation to which he had adhered (and which he had thought to explicate and enrich) was fundamentally flawed and should be replaced with a superior “orthodox Marxist” orientation (consistent with the outlook of DSA’s Bread and Roses caucus). This could explain what strikes me as the book’s contradictory qualities. As Blanc followed this path, there was a tendency not simply to follow the evidence to help craft the analysis, but rather to craft the evidence to support the new orientation.

Here are the two myths: (1) the victory of the October 1917 revolution “was made possible by Lenin’s … push to break the Bolsheviks from the Second International’s traditional stance on state and revolution,” and (2) “the October Revolution showed why soviet power should be fought for by socialists internationally, even in conditions of political democracy” (p. 343).

Of course, there are different ways to define what it means to be a Leninist. Speaking personally, I have considered myself to be a Leninist for half a century – and I have never embraced Blanc’s two “myths” as being the foundation of my Leninism. More than this, the oversimplifications in the two “myths” are easily challenged by even a halfway serious engagement with complex historical realities. But understanding what actually happened in history is at least sometimes ill-served by a polemical orientation of what makes sense in there here-and-now.

What strikes me as the key flaw crops up more than once in Blanc’s book, but it is at war with a considerable amount of insight that flows from much of his research.

Key insight

How did it come to pass that Lenin’s Bolsheviks were able to become Russia’s hegemonic force in 1917, capable of bringing about a victorious revolution? The purpose of Blanc’s study does not enable it to explain that with any clarity. His focus is on how the Bolsheviks were in many ways quite similar to non-Bolshevik revolutionaries (and sometimes on how they were inferior).

But Revolutionary Social Democracy yields up a key insight. In the period of 1912-1914 there was an amazing Empire-wide radicalization and a rising strike wave of incredible intensity and militancy. Blanc notes that “radicals” (very much including the Bolsheviks) became hegemonic in this development. “When the Tsar declared war in the summer of 1914, St. Petersburg was on the verge of insurrection, Riga was not far behind, and most other big urban centers of the empire were swept along in the rising tide of worker action as well” (p. 127).

The strengths of this study converge as Blanc makes his next point. “The hegemony of radicalism in the pre-war period undercuts the still-widespread view that a marginal but programmatically pure Bolshevik party was able to transform itself into a mass party over the course of a few short months in 1917,” he insists, bringing this to bear on the stilted conceptualization that afflicts some would-be Bolsheviks of the present-day: “Such a story may be comforting for small socialist organizations that imagine that their marginality will somehow come to an end at a moment of revolutionary crisis, but it does not conform to the facts about Russia.” He then clinches the argument: “Had revolutionary socialists across Russia not already accumulated significant mass influence under Tsarism, it is highly unlikely that they would have been serious contenders for power after its overthrow” (p. 127).

To figure out more specifically how the Bolsheviks accumulated this mass influence in 1912-1914, one would need to combine the kinds of insights Blanc draws together more generally in his book, though perhaps with greater sustained detail (similar to that supplied by Ronald Suny’s book under review). There would also need to be a more focused consideration of what Lenin and the Bolsheviks said and did.

Despite problematic qualities in Eric Blanc’s remarkable book, his contribution is well worth engaging with by all who care about the history and future of revolutionary socialism. But then came Stalin. Which leads us to the other volume under consideration.

Liberation and tyranny

Ronald Suny’s Stalin, Passage to Revolution is not a sweeping survey of historical sociology that doubles as a political intervention into the here-and-now. It is, quite simply, a magisterial contribution to the field of Russian and Soviet history. In some ways, it is the best book on Joseph Stalin that has ever been written. Boris Souvarine, Leon Trotsky, Isaac Deutscher, Robert C. Tucker, Roy Medvedev, Oleg Khlevniuk, among others, have provided essential material that is not offered by Suny. But for the period covered by Suny’s book (1879-1917), there is nothing that matches its depth, detail, and analytical quality.

The obvious question is why this massive volume ends on the eve of the 1917 revolution. On the face of it, we are presented with a truncated account. If the person described in this book had died on the revolutionary barricades or amid the horrors of the Russian Civil War, we would not know him as the Symbol of Tyranny he has become. He would be one interesting figure among many – someone commonly underestimated, in some ways problematical, but in significant ways impressive and even heroic.

Suny has for many years been immersed in researching the kinds of things that Eric Blanc presents as innovative revelations. Here they are simply yet intricately woven into a beautifully written and incredibly coherent narrative – a massive tapestry bringing history to life. An issue clearly concerning the author informs the very structure of this biography. How was it possible for a freedom struggle that was so very good and inspiring to have turned out as it did? How could a tyrant so monstrous and murderous have arisen from the very heart of the powerful and impressive revolutionary collective that was Bolshevism?

Stalin as a person and a comrade

The complex layering of contextualization – family, gender, community, class, religious and secular ideologies, Georgian ethnicity, Russian domination, the dynamics of revolutionary struggle, the detailed actualities of Bolshevism – is akin to what some call “thick description.”

Suny employs careful documentation, filters out political biases, and dispenses with superficial speculations and “psychologizing” all-too-often employed to help us “understand” Stalin. And something remarkable happens. We get a clear view of the person who was Josef Dzhugashvili: a little boy and youngster called Soso, the post-adolescent revolutionary Koba, finally the seasoned and increasingly authoritative Bolshevik who chose the name Stalin. From what Suny systematically develops, an actual human being emerges, a person animated by the life-force that is in us all, a vibrant personality with dark sides but also genuine strengths.

The personality of this comrade had contradictory dimensions. “The boys roamed together in neighborhood gangs and learned the fundamentals of loyalty, honor, self-esteem, and how to deal with adversaries,” Suny tells us of young Soso. “He grew up learning to defend himself, to play rough, and in the competitive world of the street to do what he thought was necessary to win” (pp. 31, 33). We also see his early evolution from sincere Christian to sincere atheist, a young rebel poet and essayist pushing against the authorities. Such qualities blended with the political commitments of a young revolutionary in the anti-tsarist underground. “Before 1917 Stalin was animated by a complex of ideas and emotions, from resentment and hatred to utopian hopes for justice and empowerment of the disenfranchised” (pp. 693-694). “Idealism and ideology, as well as resentment and ambition, impelled him to endure the risks and recklessness of a political outlaw,” notes Suny. “He hardened himself, accepted the necessity of deception, ruthlessness and violence – all these means justified by the end of social and political liberation” (pp. 4-5).

Some comrades concluded that Soso was “an incorrigible intriguer,” and some contrasted him to another Bolshevik organization man, Yakob Sverdlov, “who cared for people and whom everyone loved,” whereas Stalin “was closed up and morose” (pp. 144, 537). On the other hand, a comrade who was with him in Siberian exile remembered that “he would joke a lot, and we would laugh at some of the others. Comrade Koba liked to laugh at our weaknesses” (p. 406). Another recalled that he “enjoyed playing with her children, loved singing and dancing, and even provided folk medicine to the local peasants. He read and wrote late into the night” (p. 548).

Lenin and others encouraged him to develop his understanding and utilization of Marxist theory, and he gained some authority as a theorist on “the national question.” But his greatest strengths were as an organizer. During the period of recruitment and patient contact work, he organized socialist educational classes, oversaw the composition and distribution of leaflets, and helped with the editing of left-wing newspapers. During the period of armed struggle flowing from the 1905 upsurge, he helped organized terrorist hit-squads and bank robberies. He had experience in organizing protest demonstrations and strikes. He was also a seasoned faction fighter, and a capable organization man in helping to hold the Bolshevik party together and move it forward. This proved difficult in his native Georgia, however, where a left-wing variant of Menshevism became far too strong, and where some of Stalin’s early mistakes undermined his own authority. This facilitated his shift away from the borderlands, to become by 1912 a national (or empire-wide) leader within the Bolshevik movement.

Most times Stalin was inclined to follow Lenin’s lead, and this was certainly the case in the revolutionary year of 1917. “In 1917 the Bolsheviks operated not as a tightly centralized party in which orders that came down from above were faithfully carried out without question,” Suny tells us, “but as a loose and disputatious collection of strong-minded activists who had to be persuaded of the right course to take” (p. 623). In debates over party history in the early 1920s, Stalin described these realities and went on to assert that “our Party would be a caste and not a revolutionary party if it did not permit different shades of opinion in its ranks.” He added that through much of Bolshevism’s history “there were disagreements among us” that did not damage the integrity of the organization. Suny feels compelled to add a comment: “In retrospect, had Stalin heeded his own words and permitted ‘different shades of opinion’ within the party, a different Communist Party would have emerged than the one forged under Stalin” (p. 612).

The book ends before that, however, on the eve of the Bolshevik Revolution. One hopes for a second volume to bring the story up to an exploration of Lenin’s last struggle, and the rise of oppositions to the Stalinist degeneration of the revolution. The story in this volume concludes with only a peek into the future (pp. 694-695):

Over time the humane sensibilities of the romantic poet gave way to hard strategic choices. Feelings for others were displaced or suspended and were trumped by personal and political interests. … Empathy was replaced by an instrumental cruelty. Once in power those earlier emotions and ideals were subordinated to the desire to hold on to the power so arduously and painfully acquired. The possession of power became a key motivator as the imperatives of the new conditions in which the Bolsheviks found themselves forced them to make unanticipated choices. … The boy from Gori became a “great man” – that is, a powerful arbitrator of the fate of millions. His decisions as head of state and party decided who would live and who would die.

Socialism in one country

In such a continuation of Suny’s account, we will find Stalin’s momentous confrontations with Trotsky – suggestively implied here with the comment that “the two men, both ambitious and self-important, were as different as salt and pepper in their public manner” (p. 352). More essential than personal attributes were underlying political orientations: Trotsky’s revolutionary internationalism and Stalin’s insular inclination toward “socialism in one country.”

Suny fleetingly appears to give credence to the argument by Stalin scholar Erik van Ree that his inclination accorded with the views of Lenin himself, as expressed in a relatively obscure text of 1915. But Lenin’s thoughts (often repeated) were explicitly expressed in Letter to American Workers: “We are banking on the inevitability of the world revolution … as it were, in a besieged fortress, waiting for the other detachments of the world socialist revolution to come to our relief.”

Despite a global upsurge, however, the world socialist revolution did not triumph. Within the confines of the besieged fortress, Stalin’s final evolution took the form through which the world would come to know him.

Notes

[1] Eric Blanc, “The Rosa Luxemburg Myth: A Critique of Luxemburg’s Politics in Poland,” Historical Materialism 25.4 (2017/2018), p. 5.