‘Maduro has done tremendous damage to the left’: An interview with Atenea Jiménez (Alliance for Sovereignty and Democracy, Venezuela)

Atenea Jiménez is a Venezuelan sociologist and co-founder of the National Network of Communal Activists and the Campesino University of Venezuela Argimiro Gabaldón. Currently living in Spain, Jiménez helped initiate the new Alianza por la Soberanía y la Democracia (Alliance for Sovereignty and Democracy, ASD), which is bringing together various Venezuelan left movements and activists.

In this interview with Federico Fuentes for LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal, Jiménez explains the origins and objectives of the alliance, and its views on the Nicolás Maduro government and traditional right-wing opposition. She also discusses how the new Donald Trump presidency might impact Venezuelan politics, and the need for solidarity with Venezuela’s left.

Could you tell us a bit about ASD?

ASD involves diverse left currents who have united to promote a vision for the country and help recuperate democracy and sovereignty. The alliance includes various left and humanist organisations as well as left figures that supported former president Hugo Chávez while maintaining a critical stance, which have been raising the alarm for sometime about the direction of the country. It also involves left-wing organisations, movements and parties that did not support Chávez. We have not published the names of the organisations involved for security reasons, as the situation in Venezuela is very complicated. But it involves an important number of groups, both in quantitative and qualitative terms, as well as a range of university professors, personalities from the arts and culture, and, above all, ex-ministers from the Chávez and Maduro governments.

We were meeting and debating prior to the July 28 [presidential] election. ASD is the result of a long debate given the differences among us. We have not always had the same assessment of the political conjuncture or recent history. But we have come together because we share a common assessment of the situation and want to work together. Now we have an identity, name, strategy and tactics, and have set ourselves some common tasks to begin working together in practice.

Some might ask: why an alliance “for sovereignty and democracy” given the Bolivarian revolution and the Chávez government that led it had been associated with defending sovereignty and expanding democracy? What has the Maduro government’s policy been in these areas?

The Maduro government has become authoritarian — today we define it as a dictatorship. But this did not happen abruptly, it is the result of a steady process of violating the constitution and laws passed under the Chávez government, and of bypassing existing democratic institutional frameworks. Of course, the Chávez government also had its institutional weaknesses and questionable political conceptions and practices, such as converting the Bolivarian National Armed Forces into Chávez’s own political party. But, at the same time, the Chávez government generated a broad process of popular participation that extended beyond just elections. We can say that there are continuities but also discontinuities; and that today there are new and terrible elements [that did not exist under Chávez]. The Maduro government has basically thrown out the constitution. Right now there is no constitution in practice, the population has no rights. The government has violated the entire legal-judicial framework that we as Venezuelans voted for [in 1999, when the new constitution was approved in a referendum].

Moreover, our sovereignty has also been violated. By this we mean sovereignty in its double sense. We mean national sovereignty, which has to do with defending our territory, the assets of the republic, its resources and population. But we also mean popular sovereignty, which according to the constitution is exercised both through elections and participatory and protagonist democracy — popular assemblies, direct democracy, etc. The right to vote and direct democracy have both been tossed aside. When a decision made by an assembly goes against what those in power want, they simply ride roughshod over it or jail the comrades. Various comrades involved in building popular power have been jailed. So too workers, indigenous activists, campesinos, people involved in building communes.

The entire process that occurred [under Chávez] has been progressively dismantled. Given the gravity of the situation, we have decided that it is up to us to struggle — like we did before Chávez and during the Chávez government (which had its own contradictions) — for the rights of workers and society in general. We must fight for the constitution, which is what unites us as Venezuelans. We may or may not agree with everything in it, but it is the constitution that we came up with and voted for. We cannot bypass it; we must instead rescue and return to it. Another axis of our campaigning is to free the political prisoners. This is a struggle for justice and human rights that today unites Venezuelan society as a whole. It is crucial to ensuring prisoners are not used as a weapon of negotiation and a means to demobilise and demoralise society’s rebellious spirit.

What then is your opinion of Maduro’s planned constitutional reform?

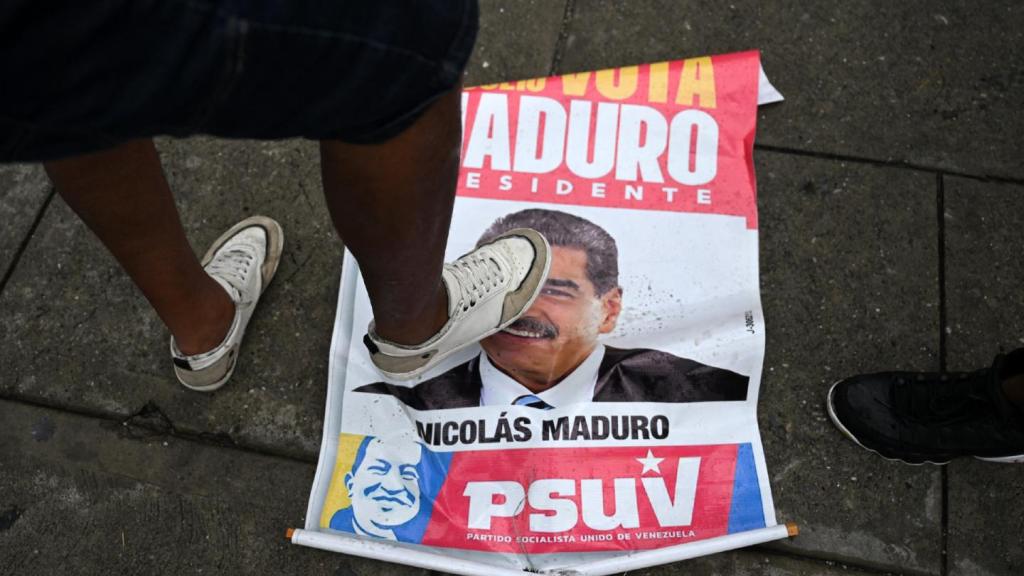

This proposal seeks to bring the constitutional framework in line with his dictatorship. Twenty-first century dictatorships are not like those of the past century, when they did not bother with appearances. Today you have to maintain a certain pretence, do some damage control. We are self-evidently dealing with an attempt to guarantee the dictatorship’s continuity within a framework of “legality”. The government has realised it will never again win an election. On July 28, it lost in every state; Maduro won in only very few polling places and neighborhoods.

Of course, ASD does not support this proposal [for constitutional reform]. Moreover, society as a whole rejects it, because it is very clear that the Venezuelan people have become more politically aware, that they know what this is about, and they will not allow the system that was born out of the July 28 elections to be consolidated.

What danger does Trump’s return to the White House represent for Venezuela’s sovereignty and democracy?

The traditional opposition is expecting a lot from Trump. We will have to wait and see, but I think the expectations that Trump will do something important about Venezuela are mistaken. Instead, everything seems to indicate that Trump will dedicate himself to resolving domestic issues — given he has more than enough of these — though, of course, this will involving taking international measures, as we have already seen with Panama, Canada, the Gulf of Mexico, etc

What we can see is a second Trump presidency that is focused on tearing down domestic and international institutions, that disregards all powers and seeks the collapse of multilateral organisations — which it must be said have also committed historic errors by undermining the sovereignty of certain countries and peoples’ free self-determination. We are also witnessing the use of migrants as a bargaining chip for oil in Venezuela’s case and the deportation of prisoners to El Salvador, a kind of bio-power based on super-exploitation of prison labour to generate large profits for capital. In this sense, there are many elements of Trump’s policies that complement Maduro’s.

Despite this, the traditional right-wing opposition continues seeking to win support from Trump for further foreign intervention, whether through more sanctions or a military invasion. What is your view of the current opposition leadership?

It is important to look at this issue in depth, given there exists a lot of confusion over the traditional opposition, especially internationally. To understand Venezuela today, we have to apply a dialectical analysis and understand that politics is not static. Party politics today are nothing like they were between 2014-19.

To start with, in order to characterise the government we have to understand that Maduro is allied with the capitalist class and has adopted policies that perfectly align with a neoliberal program: deregulation, casualisation, exploitation, elimination of salaries, enormous profits for business owners, handover of territories to multinationals, etc. Faced with this, the parties of the capitalist class — the main opposition parties [to Chavez and Maduro] — have gone into crisis, precisely because a large part of that capitalist class which previously backed them and whom they represented, is now with Maduro.

This crisis forces us to ask the question: who do these parties represent? They no longer represent the capitalist class, because Maduro represents the capitalists: those it created, those that emerged under Chávez and those that historically existed and which we call the “masters of the valley”. That is why the traditional opposition parties have been moderating their views. I am not saying they are not neoliberal parties or that there are no extreme right-wing parties within the opposition — although there is also an extreme right in government. But the opposition has shifted its conception of the situation as a result of no longer being backed by the capitalist class.

The other thing is that Venezuela has historically been an anti-neoliberal country and the majority of the Venezuelan people today are basically social democratic: they want to live well; they want rights, services and living conditions that allow them to satisfy their needs; and they want to live in democracy. This majority voted for opposition parties. As did a minority part of the population that continue to defend the achievements of the Chávez government.

This has led many to ask internationally: “How did the country go from everyone voting for Chávez to everyone voting for María Corina Machado?”, because people basically voted for her. Well, the explanation lies in this contradiction. Evidently, the opposition leaders come from the capitalist class — no one can deny that — but today they in some way represent that majority that aspires to a free and dignified life, and therefore voted against Maduro. They see hope in Machado, but ultimately do not support a revamped neoliberal program. That is why the opposition find themselves caught in this severe contradiction: their class extraction is capitalist, but those that politically support them are mainly workers who do not support Maduro and his neoliberal policies.

Furthermore, our analysis also has to take into account the international forces at play on either side, with China, Iran and, above all, Russia, on one side supporting Maduro, and the United States (with Trump’s diffuse support) and, to a lesser extent, the European Union supporting the other side.

This is the panorama of contradictions that we have. Faced with this, we propose constructing a politics for the workers, the campesinos, the popular movements, for the Chavismo which continues to revindicate Chávez but has serious criticisms about what has happened [under Maduro], and for the majority that wants to live in peace and democracy.

But if the traditional opposition has the support of the majority, why does it continue to look outside the country for help to remove Maduro?

Because the liberal conception of politics is very idealist and has little perspective when it comes to building a movement. If you analyse the traditional opposition, it has always had support: [opposition candidate Henrique] Capriles obtained a large number of votes [in the 2012 and 2013 presidential elections]; they mobilised an enormous march on April 11 [2002, as part of the coup attempt against Chávez]. There have been moments when they were able to ride an important wave of support. But this has never translated into organic self-organisation: it never led to leaps in organisation, much less organic self-organisation.

Obviously, that is difficult today with a government that says it represents a “civic-military-police alliance” — this alliance of state terrorism is basically its main strength. But the traditional opposition has never sought to build a movement, to build popular strength, to build organisation. That is why, with the consummation of the July 28 electoral fraud seemingly closing off the electoral road, the only option they can envision is obtaining support abroad to generate some kind of internal change.

We believe it is wrong to place Venezuela’s domestic affairs in the hands of the US or any other country. Hoping for a solution to come from outside of the country is a sign of great weakness. A genuine opposition needs to root its work, plans and program within Venezuelan society and focus on building an alternative within Venezuela, though this does not mean refusing to accept international support and solidarity.

It has to do with different ways of conceiving of and doing politics. We believe in building, in activism, and that the people must have protagonism. But for them, people organising themselves and assuming protagonism is a risk, because when that happens people become a subject in and for themselves, and liberal politicians see that as dangerous.

Why do you believe the traditional opposition has been able to channel the discontent that exists with Maduro and not a left opposition, either from within or outside Chavismo?

The truth is that the parties and movements that backed [Chávez's] project entered into an important crisis when it descended into authoritarianism and dictatorship [under Maduro]. There are diverse interpretations for why this happened — in fact, there still are. We should have a single platform involving everyone, but this does not exist because of these different assessments.

It also has to do with the government’s policy of repressing the left. The government has been much more repressive towards the left than the traditional opposition. Maduro’s power bloc have clearly identified that there is a battle being waged over the meaning of left wing, over the significance of Chavismo. So, it has not allowed new [left-wing] parties to emerge in this context. As for already-existing parties, Maduro stripped them of the ability to participate in elections. There are also a number of leaders in jail or being persecuted.

At the same time, there is a need for a profound self-criticism of the left’s sectarianism, of campist views and undialectical analyses that see the world as though we are still in the Cold War, of how we handed over the political initiative. I wonder what the pro-Putin left is thinking today, given his alliance with Trump? What anti-imperialist spin will they give to this? In sum, we need a more ruthless assessment [of the left’s errors], but one free of notions of Judeo-Christian guilt.

What is the current state of the movement that made up Chavismo’s base?

The popular movements, the campesino movements, the urban movements, etc have of course been greatly affected. There has been a process of dismantling the social fabric, of strong [state] intervention into society, of social-political control over society. This has had a tremendous effect, because the fabric of society requires confidence and the building of networks and spaces where people can come together.

Today in Venezuela it is very difficult to hold a meeting or assembly like we used to. It is super complicated because many leaders of the UBChs [Unidades de Batalla Hugo Chávez (Hugo Chávez Battle Units), the local units of the governing Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela (United Socialist Party of Venezuela)], as well as some sectors that used to be part of the popular movement, operate much like a political police. The Ministry of Communes itself issues instructions to them to monitor people in their community. There are no safe ways to organise. It is quite hard to say this, but it is there for all to see. And, of course, this has an impact on the strength of those socio-territorial movements that existed and continue to exist today. They have had to readjust, in terms of strategies and tactics, in order to continue doing politics in this new situation.

There are also other elements — migration, economic crisis, crime — that have had an impact, but spaces for organising still exist. Most importantly, there is still a spirit and willingness within society to fight and build; to find ways to struggle against the collapse of [Chávez’s] project and to build anew. Those of us who for many years have been working as grassroots activists are seeking ways to come together. It is a positive sign that, despite the adversities, there remains a reserve of activism, organisation and organic self-organisation.

In its statement, the ASD says that Edmundo González should assume the presidency. Are you not concerned about what this might mean for democracy and sovereignty if a candidate backed by the extreme right and US imperialism takes power?

The first thing to say is that we already have to confront an extreme right in the form of the Maduro government, behind which ultimately stands the military-party.

Second, I believe that [Edmundo González] won the elections, and that when you participate in elections, whoever wins should assume power. Of course, democracy is not perfect anywhere; there are more or less problems to overcome everywhere. But wherever you have votes and respect for institutionality, even with those problems, whoever wins should assume power. We say González has to assume the presidency because otherwise we, as the left, are saying that we refuse to respect the will of the majority if we do not like who wins. I think that is very dangerous. In democracy, you have to accept that at some point you might lose and dedicate yourself to further building up your strength.

Are we scared? I do not think we are scared. Rather, we have conviction based on experience. There are moments when movements, the organised people, have presidents that are not on the side of the workers and their demands. In those moments, we have to organise ourselves in such a way as to influence society and change the existing state of affairs. If González becomes president, the only thing left for us to do will be to make use of the democratic political instruments at our disposal. We must build a left current, a humanist current, an organisation with a program that can win people over, that has things to say to society and that has the strength to overcome the contradictions we face.

What we believe is that, right now, the main contradiction we face is democracy-dictatorship. I am not saying that there are no other contradictions, those other contradictions exist: capital-labour, humanity-nature, imperialism-nation, etc. But the primary contradiction today is democracy-dictatorship, because if we do not have a republic, we have absolutely nothing. We must first rescue the republic. This does not mean that if González comes to power everything will be resolved in Venezuela. New contradictions will emerge, and we will have to prepare for those. But right now we have to rescue our sovereignty and democracy.

To prepare ourselves for this we are forming Núcleos de Soberanía y Democracia (Sovereignty and Democracy Nucleuses), which are spaces for debate in our communities. We want to build a large movement of movements, with a program based on an analysis of our reality, that makes proposals to the country, and that not only builds in the now but permanently into the future. We want to make sure this is not just a one-off explosion, a conjunctural thing, because Venezuelan society needs an ongoing counterpower.

Some would say that given the world we live in, the primary contradiction in Venezuela is imperialism-nation. How do you respond to this?

Clearly that is one of the contradictions at play. But, as I said, it is not just US imperialism; Russia and China also have influence over Venezuelan politics and our natural resources. Limiting or restricting the imperialism-nation contradiction to just US imperialism is a big mistake. We need to broaden our view. Today there are various imperialisms in the world and there are emerging nations with imperialist pretensions. Evidently, amid these contradictions, we must have this debate as a country. But it is an issue that we should analyse through a critical, rather than campist, lens.

We defend the free self-determination of our peoples. We are, of course, against foreign military intervention and any type of foreign intervention in our domestic affairs. There is no justifiable reason for the sanctions [imposed on Venezuela]. But it also has to be said that the Manichaen view that says the country was destroyed by the sanctions is not entirely correct. When you analyse the situation, there was evidently a process of economic decline prior to the sanctions. There is more than enough evidence to prove this. Only after this did the sanctions impact society.

The ASD statement also says the current situation “obliges us to forge a broad and indestructible popular, social and political unity that tirelessly builds the most broad, diverse and participative organisation possible, one dedicated to saving the republic.” Who do you envision as part of this unity? What is needed to “save the republic”?

We envision, for example, trade unions, human rights groups that are doing outstanding work with the families of political prisoners, campesinos and the campesino movement, popular movements. We also envision as part of this those organisations and parties with which we agree on certain issues. We are calling on everyone who wants to fight to rescue the constitution, the republic and popular sovereignty to build this space of unity. We want to make sure that anyone who wants to fight is included, independent of our ideological-political positions. This has historically been known as a united front: an alliance focused on resolving the primary contradiction facing the country. This unity does not have to extend to other issues; we do not have to agree on everything. But we should be able to agree on the most important and relevant aspects, and work together on some tasks. For example, in terms of workers, we should be able to work together in the different spaces that exist for unions to come together.

Our aim is to build a grand movement of movements that incorporates a good part of society on a sectorial and territorial basis, and that contains within it the most diverse plurality possible. We want a huge movement with a minimum program that unites us all and allows us to walk together through this complex and complicated moment for Venezuela. I am not talking about a program for the country, but a minimum program behind which we can walk and advance together. One of the most difficult things to do is build unity in diversity, but this is what we need right now.

And, above all, we need organic self-organisation to rescue the republic. Building a movement of movements requires organic self-organisation, which we are trying to promote by building nucleuses, nodes and networks in various places, including among the diaspora, and incorporating forms of online and creative and effective activism. These nucleuses need to be built in order to then link up in a kind of network of networks that can resolve the challenges of this new reality in Venezuela.

The main point is to walk together. As we do this we will undoubtedly be able to move forward on further issues. That will create the possibility of looking towards a political change in Venezuela — a change that comes from our proposals, from the proposals emanating from society and from the various diverse sectors of the Venezuelan people.

Many left organisations and individuals outside of Venezuela have worked in solidarity with the Venezuelan people and the Bolivarian revolution over the past 20-25 years. Given that the situation has changed during this time, how do you see the question of solidarity today?

The left has an essential task, which is to break with certain campist views and open up the debate to include left voices that are building concrete alternatives in Venezuela. Rather than adopted highly polarised positions, the left internationally should try to comprehend our situation a bit better. This requires listening to those people who are risking their lives to build such alternatives in Venezuela.

We are fighting against the discourse and practices of a right-wing that pretends to be left when it comes to the Maduro government. We are also combating the neoliberal discourse and practices of the right-wing opposition. But, on top of this, we are against that section of the international left that attacks us simply because we are building an alternative. Those sectors, movements and parties of the international left that, in one way or another, continue to support Maduro and attack left movements and parties in Venezuela have caused a great deal of damage. Maduro too has caused tremendous damage to the left internationally, passing himself off as “left” while keeping 2000 political prisoners in jail and a society persecuted in their own homes.

I understand it is complicated and that often people cannot comprehend the current concrete reality of Venezuela from outside. But, as a bare minimum, there should be a serious attempt to comprehend, analyse and inform oneself of this reality, and to open up international spaces for the [Venezuelan] democratic left. We need to share experiences and create spaces where we can build together. That is the only way that, in the face of rising illiberal, libertarian and neo-fascist forces, among others, we can strengthen this two-way relationship in which those of us who are building left spaces in Venezuela can help the left in other parts of the world, and vice versa.