South Africa: The populist threat and the response of the left

First published at Amandla!

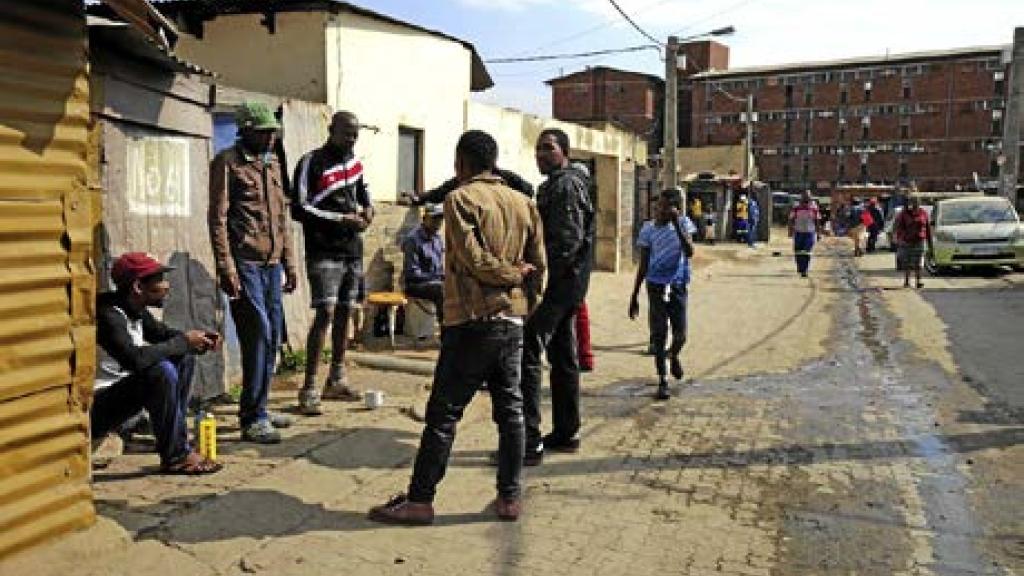

The need is greater than ever for a consolidated voice of the working class and the poor. On the one hand, daily community protests seem to indicate a population that is not by any means apathetic. But when it comes to elections, the majority don’t participate. No political party has been able to capture the imagination of the mass of people who experience unemployment, sewage in the street, erratic water supply, unaffordable electricity and intolerable levels of gender-based violence. Yet enough of those people are desperate and sufficiently concerned to protest.

There are a number of candidates vying to capture this imagination. The field is becoming crowded. But they are by no means genuine supporters of the interests of the working class and the poor.

The left is absent

The brutal truth is that, with very few exceptions, the right is capturing the mood of dissatisfaction much more effectively than the left. All over the world, there has been a dramatic shift to the right. What was once centre-left social democracy is now so far to the right that it is almost indistinguishable from the conservatives — equally wedded to neoliberalism, militarism, islamophobia and anti-immigrant rhetoric.

In South Africa, we have two major problems. Firstly, the key social force, organised labour, is largely absent from the scene. It should be pioneering an alternative politics to the ruling coalition, but unfortunately, it is either in bed with the majority party in government or too weak and disorganised to play this role. In the case of Cosatu, they may, every now and then, complain about the ANC. But it’s like a toxic relationship. The next night, they are in the same bed again — bickering but still together.

The alliance with the ANC in government has also created a huge divide between its leadership and members. Today, Cosatu, by virtue of its alliance with the ANC, is in effect in an alliance with the DA through the ‘Government of National Unity’.

Sure, now that the austerity ANC policy of its alliance partner is biting hard in health and education, there will be a token protest. It seems that 7 October is the day on which workers will be asked to sacrifice their salaries and stay at home. Everybody knows that this, on its own, will make no difference. But Cosatu is simply incapable of mounting a serious, sustained campaign against its alliance partner.

The other components of organised labour — Saftu, Nactu and Fedusa — are too weak, fragmented and politically incoherent to represent a viable alternative.

To defeat the strategy of austerity would require the kind of intelligent, rolling and continuous mass action that, from time to time, the French trade unions show us. The political will is simply lacking.

As for the SACP, it has lost all capacity to act as a party. It has been reduced to being nothing more than the political commission of Cosatu, ensuring Cosatu remains loyal to the ANC, regardless of its neoliberal agenda.

Populist and pseudo-left

The second problem is that the space vacated by labour has been occupied by a motley collection of political forces, which we often try to capture with the label ‘populist’. Into this bag, we can put MKP, the EFF and other off-shoots of the Radical Economic Transformation (RET) faction of the ANC. Of course, the PA, Action SA and National Coloured Congress, to name a few, represent the right-wing component of the populist fringe.

Their occupation of the space is based on putting forward simplistic, opportunistic and contradictory political platforms. They believe these will appeal to those suffering from the economic and social disintegration presided over by the ANC/SACP/Cosatu alliance.

The challenge to the left is to popularise our message that it is not immigration (with or without documents) which is taking jobs. There is plenty of evidence that immigrants contribute to the growth of the economy—they create jobs. In fact, it is foreign and domestic capital that is taking jobs by taking their money out of the country. It is the government that is taking jobs by signing trade agreements that allow in masses of foreign goods. In fact, they have destroyed whole industries. But ‘Abahambe’ remains the intuitive response for many people.

MKP and EFF have policies in favour of nationalisation of the commanding heights of the economy. But nationalisation can be in the service of capitalism, as well as a challenge to it. And, as we know, it can also be a smokescreen for ‘state capture’ — in the control and for the benefit of a parasitic layer of the Black middle class.

MKP reinforces this impression with its opposition to ‘white monopoly capital’. Not, you notice, capital itself. To paraphrase a recent document from Saftu What is left? What is not left?, the Left don’t fight against capitalism so that we can replace the white capitalist class with a black capitalist class.

The EFF is, on paper, also anti-neoliberal, advocating a central role for the state in directly delivering services. They advocate the return to the public sector of outsourced service provision. Yet its leaders are happy picking the fruits available only to the privileged. And again, they are not explicitly anti-capitalist.

What is left?

To be left and anti-capitalist requires a deep commitment to democracy, to fighting patriarchy and to struggling for a feminist perspective, not just in words but in practice. It also requires confrontation with capitalism’s assault on nature, and a rejection of productivism and extractivism.

And the same is true in the struggle against imperialism. It is easy to be against western imperialism; in South Africa, we are not short of reasons. But what about similar practices from newly emerging powers like China and Russia? The politics of ‘our enemy’s enemy is our friend’ are opportunistic. They turn us against the efforts of dominated classes and nations to free themselves from national oppression and foreign domination.

Matched against these criteria, both MKP and EFF fail dismally. A party which pledges itself to prioritise traditional law cannot be regarded as feminist, let alone one which has committed itself to shipping off pregnant teenagers to Robben Island. That’s MKP.

Nor can a party that humiliated and then demoted one of its representatives (Naledi Chirwa) for missing a parliamentary session because she was looking after her sick four-month-old daughter. Or a party with a military structure in its constitution. That’s the EFF.

The danger we face and the task ahead

Our current situation is filled with danger. We have a coalition government which represents the last gasp of the non-populist, neoliberal right wing. We have said many times that neoliberalism is simply incapable of solving the most fundamental of our problems — mass unemployment, effective delivery of services etc. And the ANC-DA Alliance is more deeply committed to neoliberalism even than its predecessors.

So, by the next election in 2029, if the coalition lasts until then, the GNU will have been a failure. It is possible that capital will have disciplined it sufficiently to get the ports and trains running again. After all, they need them for their profit, hence the Vulindlela project. But there is no way that the other fundamental problems will shift significantly. We can say with confidence, if also with desperation, that there will be no significant impact on real unemployment. So unless some form of credible left movement is able to emerge from the wreckage of our popular organisations, the most attractive options are likely to be MKP, EFF and PA.

That is how vital and how urgent is the task of building an alternative.

At the last local elections, a few popular, community-based organisations set up their own political organisations so that they could obey the electoral rules and stand for election. Unlike many other organisations, the day after the election they didn’t disappear, only to reappear five years later. They were there, to try to hold their councillors to account and to continue to be the voice of the community.

It hasn’t been an easy ride. But the rooting of elected representatives in really existing popular organisations is vital. The task now is to build united, community-based organisations which take up, in a militant and focused way, the issues that concern the community. The small number of green shoots that have appeared are a hopeful sign.

Also, a possible hopeful sign is the emergence of a left in the SACP, talking about building popular organisations, based on local issues. They say that this is no time for sectarianism — the popular movement must be built, and we must work together. Political differences are secondary to the urgency of such a task.

History is not sanguine about this possibility, but the message is the right one. The left must come together around such a project and, from those hundreds of organisations all around the country, build a movement for socialism from the ground up. All who are willing to participate honestly in such a process must be welcomed. The alternative doesn’t bear thinking about.