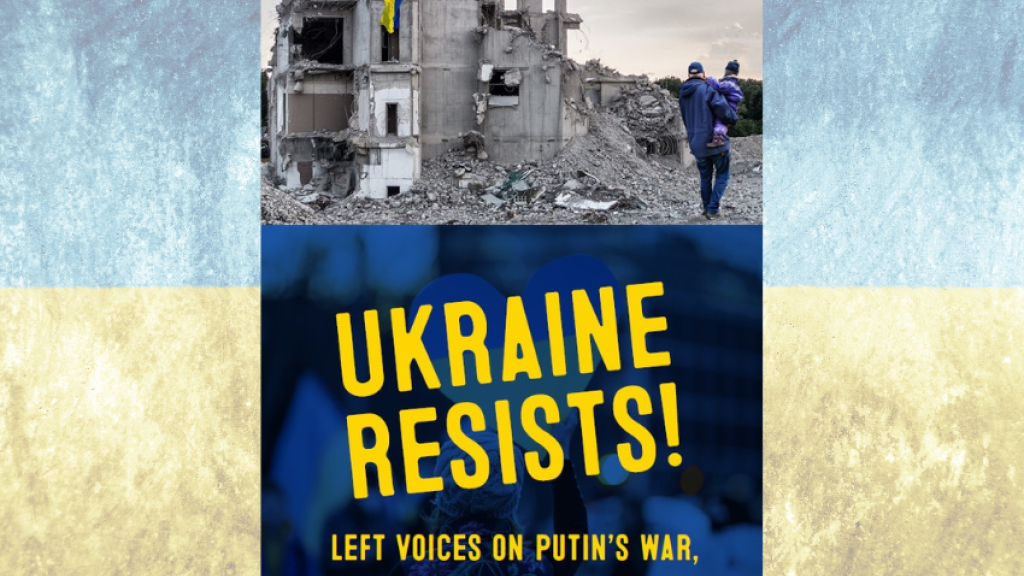

Ukraine Resists!: A leftist guidebook on Putin’s war, NATO and the future of Ukraine

Ukraine Resists!: Left Voices on Putin’s War, NATO and the Future of Ukraine

Resistance Books, 2023

176pp, $25 (paperback), $15 (PDF)

Ukraine Resists!: Left Voices on Putin’s War, NATO and the Future of Ukraine is a compilation of interviews with socialists from Ukraine, Russia and elsewhere. In this review I will not deal with all the contributors or issues raised, but will focus on some key questions that are discussed.

Internal conflict and foreign intervention in Ukraine

According to Ukrainian socialist and political economist Yuliya Yurchenko, ethnic and regional conflict in Ukraine arose from a combination of domestic and international factors: “Domestic dynamics are extremely important to understanding how irresponsible, self-serving local politicians created the conditions that made foreign interventions more possible.

“In the 1990s, oligarchic groups emerged in different parts of Ukraine... By the end of the ’90s, an important bloc of energy-intensive industrial capital had emerged in the east with strong economic ties to [Russian president Vladimir] Putin’s regime, due to reliance on gas imports.

“Out of these different oligarchic groups emerged leaders who competed for political power. One was Viktor Yanukovych — linked to this Donbas industrial capital in the east — who ran in the fraudulent 2004 elections that led to the Orange Revolution, and again in 2010 against then incumbent president Viktor Yushchenko.

“Their 2010 electoral campaigns were framed at winning the votes of the majority of people in either the east (Yanukovych) or west (Yushchenko). This divisive political framing of election campaigns was pivotal in solidifying the idea of ‘two Ukraines’.”

But Yurchenko also explains the role of Russia in creating the conditions for ethnic conflict: “Russia started promoting the idea of Russky Mir (“Russian World”) [which encompasses all Russian speakers] years before the 2013‒14 events through local media outlets, particularly in Crimea and Donbas, which have the largest ethnically Russian populations within Ukraine.

“Russia’s imperial ambitions were reinvigorated with the fall of the Soviet Union. We can see this in Putin’s speeches where he refers to Ukraine as little more than a province of Russia — one without its own political subjectivity, its own culture, its own language.”

There were also economic motives for Putin wanting to control Donbas, says Yurchenko: “There are a lot of industries in Donbas — and in the south of Ukraine — that are deeply integrated with Russian industry, making components for its military and other production lines that Russia does not want to lose control over.”

Maidan rebellion

Yurchenko also explains the reasons for the protests that began in Kyiv's Maidan square in November 2013 and continued until president Yanukovych fled the country in February 2014: “The protests began with Yanukovych’s refusal to sign the agreement [with the European Union], but Maidan did not properly kick off until the night of November 30, when Yanukovych sent police to beat up protesters in the main square of Kyiv.

“After that, the protests became massive, with over a million people gathering in Kyiv, a city of just a few million people. Protesters now demanded Yanukovych’s resignation and immediate elections, with protests spreading to squares all across Ukraine, including Donetsk, Luhansk, Odesa and Crimea.

“Surveys done about a week after the protests found the main reasons people attended were police brutality, lawlessness, corruption and social economic deprivation. The EU agreement was seventh or eighth on the list.

“Maidan was not a Western-planted coup, it was an expression of dissent and frustration. It was a protest movement that had been brewing for decades. There were many protests in the years leading up to it over socio-economic problems, against predatory real estate developers, against corruption, against police impunity. People were sick of all that.”

However, the outcome of the Maidan protests was the replacement of one oligarch (Yanukovych) by another (Petro Poroshenko). Yurchenko explains this was due to the Russian intervention in Ukraine: “Putin then moved to annex Crimea and his stooges started a war in Donbas.”

Poroshenko then used this situation to win the election on the basis that he was the best person to lead Ukraine in a time of war. Yurchenko says: “He would not have won if the war in Donbas had not started. The end result was that the achievements of the revolution were hijacked by the oligarchs.”

Ukrainian socialist philosopher Daria Saburova, in an article included as an appendix, notes that another factor undermining the democratic potential of the Maidan protest movement was the participation of far right groups that “imposed a nationalist agenda”. These were a small minority of the protestors, but played a major role in confrontations with the police.

Russian intervention

In her interview, Ukrainian socialist historian Hanna Perekhoda discusses Putin’s claim that Ukraine is not a real nation, but a part of Russia that has been artificially separated: “For Putin, Ukrainians and Russians are ‘one and the same people’, while the distinct national identity of Ukrainians is the result of a conspiracy plotted by those who want to weaken Russia. Tsarist elites also believed rival powers were fueling Ukrainian national sentiment to weaken Russia. Two centuries later, Putin expresses this same obsession, which shapes both his rhetoric and political action.”

Perekhoda says that Russian intervention triggered the war in Donbas in 2014. There was discontent with the new post-Maidan Ukrainian government among the people of Donbas, but this would not have led to war without the actions of armed groups from Russia: “Even if the Donbas population had a sense of local exceptionalism, separatist desires were extremely marginal and there was minimal evidence of support for an armed uprising.”

But in April 2014, the war began. Perekhoda says: “That same month, amid a background of general apathy and disorientation, a Russian ex-FSB [Federal Security Service] officer Igor Girkin-Strelkov, together with several dozen armed people, began taking control of the local institutions, asking Moscow to send ‘volunteers’ to sustain the ‘rebellion’.”

Perekhoda adds: “Existing tensions and grievances were manipulated for a long time by both Ukrainian and Russian elites, but it is unlikely that war in Donbas would have happened without Russian military intervention. Another key factor was the support given by local oligarchs, who tried to play both sides until they were replaced by Kremlin puppets.”

These “Kremlin puppets” imposed a corrupt and repressive regime in the parts of Donbas that they controlled. Perekhoda says: “The separatist republics in Donbas have become zones of corruption, total impunity, violence and widespread injustice, where the population faces uncertainty, extreme poverty, repression and physical abuse.”

Donbas

Saburova discusses the war in Donbas in more detail. She says that while many people in Donbas were suspicious of the Maidan protests, and there was discontent with the post-Maidan Ukrainian government, this would not have been sufficient to cause a war to break out, if Russia had not intervened: “The majority attitude of Donbas residents towards Maidan ranged from indifference to hostility...

“Yet Maidan had the potential to unite not only bourgeois democratic forces, but also the working classes of the whole country around common demands. Although they were less massive, there were also pro-Maidan demonstrations in the Donbas, protests against corruption, the abuses of the police state and the dysfunctional legal system, and in favour of the values associated — rightly or wrongly — with Europe, such as democracy, respect for the law, civil and human rights, as well as higher wages and living standards.

“However, this potential was suffocated, on the one hand by the entry into the movement of far-right groups that imposed a nationalist agenda on the Kyiv Euromaidan, and on the other hand by the effort of local authorities in the East to discredit the movement.”

But suspicion of Maidan among many Donbas residents did not mean support for armed rebellion, writes Saburova: “None of this means that from the outset there was a broad popular mobilisation for independence of these regions or for their attachment to Russia, nor that the reaction against Maidan meant inevitable descent into civil war....

“It can therefore be said that without Russia's involvement, the mistrust of the Donbas populations regarding the Maidan revolution would certainly not have turned into a civil war. First, there is the immense role that Russian propaganda played in discrediting Maidan as a US-orchestrated fascist coup. The Russian media or media controlled by local pro-Russian elites — the main sources of information for the local population — spread all sorts of false information and rumours about the fate the new Kyiv government was reserving for the Russian-speaking population...

“Then there was the direct involvement in the anti-Maidan protests and the separatist uprising under the banner of the ‘Russian Spring’ of Kremlin advisers like Vladislav Surkov and Sergey Glazyrev, as well as of Russian special forces. This operation was initially led by the Russian citizen Igor Girkin (Strelkov), later to be replaced by Donetsk national Aleksandr Zakharchenko in order to give more legitimacy to the leadership of the new republics.

“Finally, from June 2014 onwards, Russia got involved in the war not only by sending heavy weapons to the local separatists but directly with the participation of Russian army units in the fighting in Ilovaisk in August 2014, in Debaltseve in February 2015, etc.”

Why did Putin invade?

Some Western leftists blame NATO expansion and the possibility that Ukraine might join NATO for provoking Putin to invade. But the Russian socialists interviewed for this book disagree.

Ilya Matveev comments: “The annexation of Crimea [in 2014] was probably specifically dictated by Russia’s fear of losing its Black Sea Fleet and its naval base in Sevastopol. For some leftists, this serves as a justification for Russia’s annexation. But can we really justify this kind of preventive aggression?

“Now, Russia is in the process of annexing even more territories from another sovereign country. This kind of preventive aggression is not normal behaviour; this kind of preventive imperialist intervention is not acceptable, and it is not justifiable.

“The problem with official Russian discourse is that it tries to conflate Russian security with Russian imperialist interests...

“In my opinion this is ultimately not about security; it is about imperialist interests and the imperial ideology that characterises the Russian regime. It has an imperial vision towards the post-soviet space, and specifically towards Ukraine. It cannot tolerate Ukraine being a sovereign country. That’s the bottom line.”

Another Russian socialist, Boris Kagarlitsky, emphasises the domestic reasons for Putin’s decision to invade. Kagarlitsky says there has been an “enormous expansion of corruption” in Russia in recent years. The rich are building “incredible palaces”, while the real income of most people is declining, and health and social services, already underfunded, are being cut further.

This situation is producing growing discontent: “One example of this was the pension reform of 2018, which faced stiff opposition.”

In this situation, Kagarlitsky, who today finds himself in jail for his anti-war views, says, Putin wanted a pretext to repress dissent, “a situation that justifies a state of emergency, whereby the people who make decisions can override any institutional or constitutional hurdle and make whatever decisions they want to make. And a war is perhaps the best way to create such a situation.”

What should we advocate?

Editor and Socialist Alliance (Australia) national executive member Federico Fuentes notes that the contributors are “unanimous in supporting the Ukrainian people’s right to resist, their right to self-determination and their urgent need to receive material solidarity from left and progressive people around the world.”

Contributors generally agree that Ukraine has a right to seek military aid from whoever will supply it, which mainly means the US and its NATO allies.

There is some disagreement over Western sanctions on Russia, however. Ukrainian socialist Vladyslav Starodubtsev says: “We need to sanction Russia so that it can not afford to pay for soldiers’ wages or more military equipment. If they can not do this, then the war will stop.”

British socialist Phil Hearse, on the other hand, opposes sanctions on Russia: “This is part of the US sanctions regime in which 39 countries have been targeted in 8000 individual sanctions against a wide range of people and companies.”

It is true that the US often uses economic sanctions to advance its own interests by weakening governments that displease it in some way. But it also uses military aid in a similar way. Arms supplies to Ukraine are intended to weaken Russia, which is seen as a rival imperialist power. I do not see a fundamental difference between sanctions and the supply of weapons.

It is true that economic sanctions can cause enormous harm to the people of the sanctioned country. The sanctions imposed on Iraq after Saddam Hussein came into conflict with the US caused hundreds of thousands of deaths from disease and starvation. Today sanctions imposed on Cuba and Venezuela are intended to lead to the overthrow of their progressive governments.

However, the left supports sanctions in some cases — notably the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions campaign against Israel. In the case of Russia, my view is that we should at least support sanctions that mainly affect military supplies or equipment for military industry. I admit it is not always easy to draw the line, since some products can have both military and civilian uses.

The road to peace

Perekhoda says the withdrawal of Russian troops is essential for peace in Donbas. But she also advocates an international peace-keeping force: “Ukraine has repeatedly promoted the deployment of an international peacekeeping force to these territories. I think there is a chance that Donbas could one day return to a peaceful life.

“But in my opinion, this will only be possible after a complete withdrawal of Russian armed forces and subsequent demilitarization of Russia. An economic and environmental reconstruction, along with the creation of the necessary conditions for democratic expression, could probably be achieved under a long-term international mandate of peacekeeping forces.”

International peacekeeping forces have a mixed record, but have sometimes played a useful role, as in East Timor for example. In the case of Ukraine, such a force might provide some reassurance to residents of Russian-occupied territories against a wave of revenge killings of alleged collaborators if Russian troops simply withdrew and Ukrainian troops immediately moved in.

Can Russia be persuaded to withdraw? Kagarlitsky argues that Putin, having stirred up a wave of jingoism among a section of the Russian population, can not make peace without antagonising these people. Hence he continues the war.

The West would like to see Putin replaced by someone else, but without any major change to the capitalist system that exists in Russia. It would like “Putinism without Putin”, say Kagarlitsky. But he also says this is unlikely to happen. The removal of Putin would be “the beginning of a much deeper crisis”.

He compares the situation to that in Russia in 1917, and predicts the “collapse” of the Putin regime: “The important thing is that there is no going back to the status quo ante. Ukraine is going to undergo tremendous changes. And Russia will undergo even deeper changes.

“As a Belarusian comrade recently said to me, we — meaning Russians, Belarusians, all of us ex-Soviet Union and ex-Russian imperial subjects — have a good tradition: Every time we lose a war, we either start radical reforms or revolutions.”